Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▼ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 May 2020

TIPZOO: a Touchscreen Interface for Palaeolithic Zooarchaeology. Towards making data entry and analysis easier, faster, and more reliableEmmanuel Discamps https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/aew5cA new software to improve standardization and quality of data in zooarchaeologyRecommended by Florent Rivals based on reviews by Delphine Vettese and Argant Thierry based on reviews by Delphine Vettese and Argant Thierry

Standardization and quality of data collection are identified as challenges for the future in zooarchaeology [1]. These issues were already identified in the early 1970s when the International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ) recommended to “standardize measurements and data in publications”. In the recent years, there is strong recommendations by publishers and grant to follow the FAIR Principle i.e. to “improve the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reuse of digital assets” [2]. As zooarchaeologists, we should make our methods more clear and replicable by other researchers to produce comparable datasets. In this paper the authors make a significant step in proposing a tool to replace traditional data recording softwares. The problems related to data recording are clearly identified and discussed. All the features offered by TIPZOO allow to standardize the data, to reduce the errors when entering the data, to save time with auto-filling entries. The coding system used in TIPZOO is based on variables taken from the most used and updated literature in zooarchaeology. Its connections with various R packages allow to directly export the data and to transform the raw data to produce summary tables, graphs and basic statistics. Finally, the advantage of this tool is that it can be improved, debugged, or implemented at any time. TIPZOO provides a standardized system to compile and share large and consistent datasets that will allow comparison among assemblages at a large scale, and for this reason, I have recommended the work for PCI Archaeology. References [1] Steele, T.E. (2015). The contributions of animal bones from archaeological sites: the past and future of zooarchaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 56, 168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2015.02.036 | TIPZOO: a Touchscreen Interface for Palaeolithic Zooarchaeology. Towards making data entry and analysis easier, faster, and more reliable | Emmanuel Discamps | <p>Zooarchaeological studies of fossil bone collections are often conducted using simple spreadsheet programs for data recording and analysis. After quickly summarizing the limitations of such an approach, we present a new software solution, TIPZO... |  | Spatial analysis, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Florent Rivals | 2020-04-16 13:27:00 | View | |

16 Apr 2024

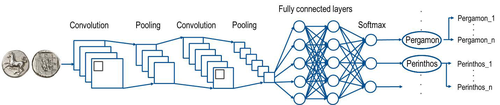

Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin DatasetSebastian Gampe, Karsten Tolle https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298077A significant contribution to the problem of unbalanced data in machine learning research in archaeologyRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by Simon Carrignon, Joel Santos and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Carrignon, Joel Santos and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper [1] presents an innovative approach to address the prevalent challenge of unbalanced datasets in coin type recognition, shifting the focus from coin class type recognition to coin mint recognition. Despite this shift, the issue of unbalanced data persists. To mitigate this, the authors introduce a method to split larger classes into smaller ones, integrating them into an 'additional class layer'. Three distinct machine learning (ML) methodologies were employed to identify new possible classes, with one approach utilising unsupervised clustering alongside manual intervention, while the others leverage object detection, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. However, despite these efforts, overfitting remained a persistent issue, prompting the authors to explore alternative methods such as dataset improvement and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). The paper contributes significantly to the intersection of ML techniques and archaeology, particularly in addressing overfitting challenges. Furthermore, the authors' candid acknowledgment of the limitations of their approaches serves as a valuable resource for researchers encountering similar obstacles. This study stems from the D4N4 project, aimed at developing a machine learning-based coin recognition model for the extensive "Corpus Nummorum" dataset, comprising over 19,600 coin types and 49,000 coins from various ancient landscapes. Despite encountering challenges with overfitting due to the dataset's imbalance, the authors' exploration of multiple methodologies and transparent documentation of their limitations enriches the academic discourse and provides a foundation for future research in this field. Reference [1] Gampe, S. and Tolle, K. (2024). Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin Dataset. Zenodo, 8298077, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298077 | Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin Dataset | Sebastian Gampe, Karsten Tolle | <p>We have implemented an approach based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for mint recognition for our Corpus Nummorum (CN) coin dataset as an alternative to coin type recognition, since we had too few instances for most of the types (classe... |  | Computational archaeology | Alex Brandsen | 2023-08-29 16:26:41 | View | |

11 Oct 2023

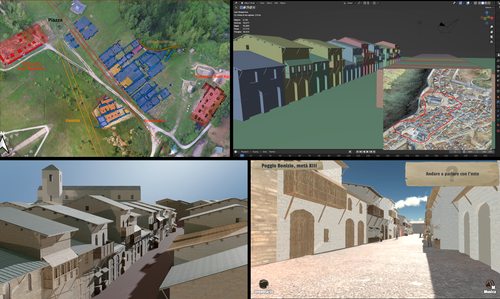

Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill ProjectSamanta Mariotti https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563Gamification of an archaeological park: The Living Hill Project as work-in-progressRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (2023) describes The Living Hill project dedicated to the archaeological park and fortress of Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi, Italy. The project is a collaboration between the Poggibonsi excavation and Entertainment Games App, Ltd. From the start, the project focused on the question of the intended audience rather than on the used technology. It was therefore planned to involve the audience in the creation of the game itself, which was not possible after all due to the covid pandemic. Nevertheless, the game aimed towards a visit experience as close as possible to reality to offer an educational tool through the video game, as it offers more periods than the medieval period showcased in the archaeological park itself. The game mechanics differ from a walking simulator, or a virtual tour and the player is tasked with returning three lost objects in the virtual game. While the medieval level was based on a 3D scan of the archaeological park, the other two levels were reconstructed based on archaeological material. Currently, only a PC version is working, but the team works on a mobile version as well and teased the possibility that the source code will be made available open source. Lastly, the team also evaluated the game and its perception through surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Although the surveys were only based on 21 persons, the results came back positive overall. The paper is well-written and follows a consistent structure. The authors clearly define the goals and setting of the project and how they developed and evaluated the game. Although it has be criticized that the game is not playable yet and the size of the questionnaire is too low, the authors clearly replied to the reviews and clarified the situation on both matters. They also attended to nearly all of the reviewers demands and answered them concisely in their response. In my personal opinion, I can fully recommend this paper for publication. For future works, it is recommended that the authors enlarge their audience for the quesstionaire in order to get more representative results. It it also recommended to make the game available as soon as possible also outside of the archaeological park. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their concise and constructive criticism to this paper as well as for their time. References Mariotti, Samanta. (2023) Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project, Zenodo, 8302563, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563 | Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of *The Living Hill* Project | Samanta Mariotti | <p>Video games are now recognised as a valuable tool for disseminating and enhancing archaeological heritage. In Italy, the recent institutionalisation of Public Archaeology programs and incentives for digital innovation has resulted in a prolifer... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Europe, Medieval, Post-medieval | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-30 20:25:32 | View | |

05 Jan 2024

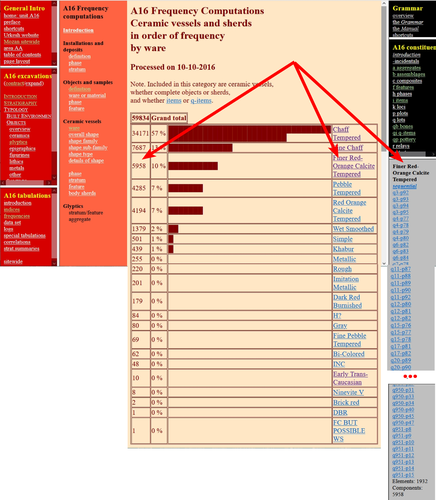

The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A Website Approach to Archaeological Typology.Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7743834Roster and Lexicon – A Radical Digital-Dialogical Approach to Questions of Typology and Categorization in ArchaeologyRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and 2 anonymous reviewers

“The density of types and the dignity of the fragment. A website approach to archaeological typology” by G. Buccellati and M. Kelly-Buccellati (1) is a contribution to the rapidly growing literature on digital approaches to archaeological data management, expertly showcasing the significant theoretical and epistemological impetus of such work. The authors offer a conceptually lucid discussion of key concepts in archaeological ordering practices surrounding the longstanding tension between so-called ‘etic’ and ‘emic’ approaches, thereby providing a thorough systematic of how to think through sameness and difference in the context of voluminous digital archaeological data. As a point of departure, the authors reconsider the relationship between archaeological fragments – spatiotemporally bounded artefacts and features – and their larger meaning-giving totality as the primary locus of archaeological knowledge. Typology can then be said to serve this overriding quest to resolve the conflict between parts and wholes, as the parts themselves are never sufficient to render the whole but the whole remains elusive without reference to the parts. Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati here make an interesting point about the importance to register the globality of the archaeological record – that is, literally everything encountered in the soil – without making any prior choices as to what supposedly matters and what not. The distinctiveness of the archaeological enterprise, according to them, indeed consists of the circumstance that merely disconnected fragments come to the attention of archaeologists and the only objective data that can be attained, because of this, are about the situated location of fragments in the ground and their relation to other fragments – what they call ‘emplacement’. This, we would add, includes the relationship of fragments with human observers and the employed methods of excavation as observation. As the authors say: “[i]t is in this sense that the fragments are natively digital: they are atoms that do not cohere into a typological whole”. The systematic exploration of how the so recovered fragments may be re-articulated is then essentially the goal of archaeological categorization and typology but these practices can only ever be successful if the whole context of original ‘emplacement’ is carefully taken into consideration. This reconstruction of the fundamental epistemological situation archaeology finds itself in leads the authors to a general rejection of ‘more’ vs. ‘less’ objective or even subjective ordering practices as such qualifications tend to miss the point. What matters is to enable the flexible and scalable confrontation of isolated archaeological fragments, to do experiment with and test different part-whole relations and their possible knowledge contributions. It is no coincidence that the authors insist on a dynamical approach to ordering practices and type-thinking in archaeology here, which in many ways comes often very close to the general conceptual orientation philosopher Stephen C. Pepper (2) has called ‘organicism’ – a preoccupation of resolving the tension between heterogeneous fragments and coherent wholes without losing sight of the specificity of each single fragment. In the view of organicist thinkers, and the authors seem to share this recognition, to take complexity seriously means to centre the dialectics between fragments and wholes in their entirety. This notion is directly reflected in the authors’ interesting definition of ‘big data’ in archaeology as a multi-layered and multi-referential system of organizing the totality of observations of emplacement (the Global record). Based on this broader exposition, Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati make some perceptive and noteworthy observations vis-à-vis the aforementioned emic-etic distinction that has caused so much archaeological confusion and debate (3–6). To begin with, emic and etic designate different systemic logics of organizing observable sameness and difference. Emic systems are closed and foreground the idea of the roster, they recognize only a limited set of types whose identity depends on relative differences. Etic systems, on the other hand, are in principle open (and even open-ended) and rely on the notion of the lexicon; they enlist a principally endless repertoire of traits, types and sub-types (classes and sub-classes may be added to this list of course). Difference in etic systems is moreover defined according to some general standards that appear to eclipse the standards of the system itself. Etic systems therefore tend to advocate supposedly universal principles of how to establish similarity vs. difference, although, in reality, there is substantial debate as to what these principles may be or whether such endeavour is a useful undertaking. In the wild, both etic and emic systems of ordering and categorization are of course encountered in the plural but etic systems deploy external standards of order while emic systems operate via internal standards. An interesting observation by the authors in this context is that archaeological reasoning in relation to sameness and difference is almost never either exclusively etic or exclusively emic. The simple reason is that any grouping of fragments according to technological (means/modes of production) or functional considerations (use-wear, tool design, relation between form and function) based on empirical evidence is typically already infused by emic standards. The classic example from the analysis of archaeological pottery is ware groups, which reference the nexus of technological know-how and concrete practices, and which rely, in a given context, on internal, relative differentiations between the respective observed practices. Yet ignoring these distinctions would sideline significant knowledge on the past. These discussions are refreshing as they may indicate that ordering practices – when considered as an end in themselves – misconstrue the archaeological process as static and so advocate for categories, classes, and types to be carved out before any serious analysis can begin. It could in fact be argued that in doing so, they merely construct a new closed system, then emic by definition. Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati propose an alternative without discarding the intuition that ordering archaeological materials is conditional to the inferential and knowledge-production process: they propose that typologies should be treated as arguments. Moreover, the sort of argument they have in mind is to a lesser extent ‘formal-logical’ but instead emphatically ‘dialogical’ in nature, as such argumentative form helps to combat the inherent static-ness of ordering practices the authors criticize, and so discloses a radically dynamic approach to the undertaking of fragment-whole matching. The organicist inclination to preserve ‘the dignity of fragments’ while working towards their resolution in attendant wholes and sub-wholes further gives rise to the idea that such ‘native digital fragments’ must be brought into systematic conversation with one another, acknowledging the involved complexity. To this end, the authors frame ordering work and typo-praxis as a ‘digital discourse’ and ask what the conditions and possibilities for such discourse are and how it can be facilitated. It is here that they put forward the idea that the webpage may provide an ideal epistemic model system to promote the preservation of emplaced archaeological fragments while simultaneously promoting multistranded and multi-context explorations of fragment coherence and articulation. The website enables unique forms of exploration and engagement with data and new arguments escaping the fixity of the analogue-printed which dominates current archaeological practice. Similar experiences were for example made in the context of Gardin’s ‘logicism’, leading to broadly comparable attempts to overcome the analogue with more dynamic, HTML/web-based forms of data presentation, exploration and discussion (7, 8). As such, Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati table a range of fresh arguments for re-thinking typology beyond and with text at the same time, to enable ‘dynamic reading’ of fragment-whole relationships in an increasingly digital world. Their proposal comes thereby close to what has been termed ‘deep mapping’ in the context of critical cartographies and other spatially-inclined scholarship in the Anglophone world (9, 10). Deep maps seek to transcend the epistemological limitations of 2D-representations of spatiality on traditional maps and introduce different layers of informational depth and heterogeneity, which, similarly to the living digital webpage proposed by the authors, can be continuously extended and revised and which may also greatly promote multidisciplinary and team-based research endeavours. In the same spirit as the authors’ ‘digital discourse’, deep mapping draws attention to the knowledge potential of bringing together the heterogeneous, the etic and the emic, and to pay more attention to ‘multiplanar’ and ‘multilinear’ relationships as well as the associated relations of relations. This proposal to deploy types and typology in general as dynamic arguments is linked to the ambition to contribute to and work on the narrativization of the archaeological record without tacit (and often unconscious) conceptual pre-subscription, countering typologies that remain largely in the abstract and so have contributed to the creeping anonymity of the past.

Bibliography 1. Buccellati, G. and Kelly-Buccellati, M. (2023). The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A website approach to archaeological typology, Zenodo, 7743834, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7743834. 2. Pepper, S C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (Univ. of California Press). 3. Hayden, B. (1984). Are Emic Types Relevant to Archaeology? Ethnohistory 31, 79–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/482057 4. Tostevin, G. B. (2011). An Introduction to the Special Issue: Reduction Sequence, Chaîne Opératoire, and Other Methods: The Epistemologies of Different Approaches to Lithic Analysis. PaleoAnthropology, 293−296. https://www.doi.org/10.4207/PA.2011.ART59 5. Tostevin, G. B. (2013). Seeing lithics: a middle-range theory for testing for cultural transmission in the pleistocene (Oakville, CT: Oxbow Books). 6. Boissinot, P. (2015). Qu’est-ce qu’un fait archéologique? (Éditions EHESS). https://doi.org/10.4000/lectures.19921 7. Gardin, J.-C. and Roux, V. (2004). The Arkeotek Project: a European Network of Knowledge Bases in the Archaeology of Techniques. Archeologia e Calcolatori 15, 25–40. 8. Husi, P. (2022). La céramique médiévale et moderne du bassin de la Loire moyenne, chrono-typologie et transformation des aires culturelles dans la longue durée (6e—17e s.) (FERACF). 9. Bodenhamer, D. J., Corrigan, J. and Harris, T. M. (2015). Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives (Indiana University Press). 10. Gillings, M., Hacigüzeller, P. and Lock, G. R. (2019). Re-mapping archaeology: critical perspectives, alternative mappings (Routledge).

| The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A Website Approach to Archaeological Typology. | Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati | <p>Typology hinges on categorization, and the two main axes of categorization are the roster and the lexicon: the first defines elements from an -emic, and the second from an (e)-tic point of view, i. e., as a closed or an open system, respectivel... |  | Antiquity, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2023-03-17 09:11:46 | View | |

Yesterday

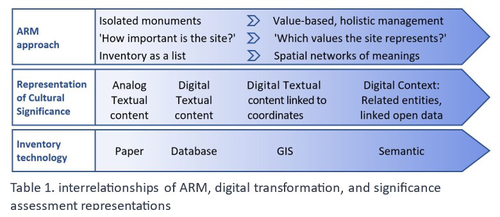

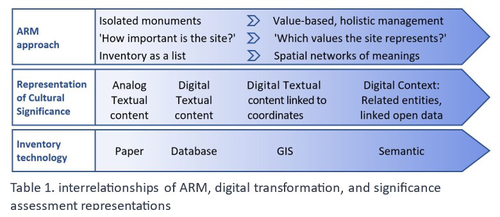

Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of MeaningsYael Alef, Yuval Shafriri https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309992How Semantic Technologies and Spatial Networks Can Enhance Archaeological Resource ManagementRecommended by James Stuart Taylor based on reviews by Dominik Lukas and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Dominik Lukas and 1 anonymous reviewer

After a thorough review and consideration of the revised manuscript titled "Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text to Spatial Networks of Meanings" by Yael Alef and Yuval Shafriri [1], I am recommending the paper for publication. The authors have made significant strides in addressing the feedback from the initial review process, notably enhancing the manuscript's clarity, methodological detail, and overall contribution to the field of Archaeological Resource Management (ARM). On balance I think the paper competently navigates the shift from a traditional significance-focused assessment of isolated archaeological sites to a more holistic and interconnected approach, leveraging graph data models and spatial networks. This transition represents an advancement in the field, offering deeper insights into the sociocultural dynamics of archaeological sites. The case study of ancient synagogues in northern Israel, particularly the Huqoq Synagogue, serves as a compelling illustration of the potential of semantic technologies to enrich our understanding of cultural heritage. Significantly, the authors have responded to the call for a clearer methodological framework by providing a more detailed exposition of their use of knowledge graph visualization and semantic technologies. This response not only strengthens the paper's scientific rigor but also enhances its accessibility and applicability to a broader audience within the conservation and heritage management community. However, I do think it remains important to acknowledge areas where further work could enrich the paper's contribution. While the manuscript makes notable advancements in the technical and methodological domains, the exploration of the ethical and political implications of semantic technologies in ARM remains less developed. Recognizing the complex interplay of ethical and political considerations in archaeological assessments is crucial for the responsible advancement of the field. Thus, I suggest that future work could productively focus on these dimensions, offering a more comprehensive view of the implications of integrating semantic technologies into heritage management practices. I don't think that this omission is a reason to withold the paper for publication or seek further review. In fact I think it stands alone a paper quite well. Perhaps the authors might consider this as a complementary line of inquiry in their future work in the field. In conclusion then, I believe the revised manuscript represents a valuable addition to the literature, pushing boundaries of how we assess, understand, and manage archaeological resources. Its focus on semantic technologies and the creation of spatial networks of meanings marks a significant step forward in the field. I believe its publication will stimulate further research and discussion, particularly in the realms of ethical and political considerations, which remain ripe for exploration. Therefore, I'm happy to endorse the publication of this manuscript. Reference [1] Alef, Y and Shafriri, Y. (2024). Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of Meanings. Zenodo, 8309992, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309992 | Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of Meanings | Yael Alef, Yuval Shafriri | <p>This study examines the shift towards a values-based approach for Archaeological Resource Management (ARM), emphasizing the integration of Context-Based Significance Assessment (CBSA) with semantic technologies into digital ARM inventories. We ... |  | Computational archaeology, Conservation/Museum studies, Spatial analysis | James Stuart Taylor | 2023-09-01 22:24:15 | View | |

14 Nov 2023

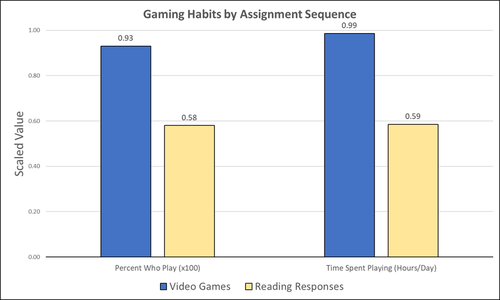

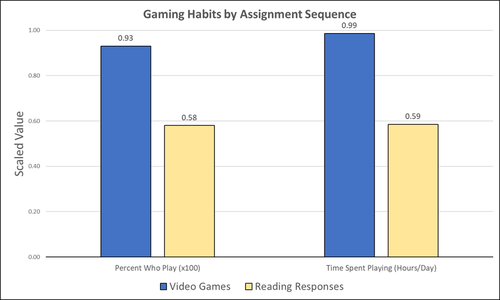

Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics ClassroomStephan, Robert https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8221286Learning with Archaeogaming? A study based on student feedbackRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Jeremiah McCall and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jeremiah McCall and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (Stephan 2023) is about the use of video games as a pedagogical tool in class. Instead of taking the perspective of a lecturer, the author seeks the student’s perspectives to evaluate the success of an interactive teaching method at the crossroads of history, archaeology, and classics. The paper starts with a literature review, that highlights the intensive use of video games among college students and high schoolers as well as the impact video games can have on learning about the past. The case study this paper is based on is made with the game Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, which is introduced in the next part of the paper as well as previous works on the same game. The author then explains his method, which entailed the tasks students had to complete for a class in classics. They could either choose to play a video game or more classically read some texts. After the tasks were done, students filled out a 14-question-survey to collect data about prior gaming experience, assignment enjoyment, and other questions specific to the assignments. The results were based on only a fraction of the course participants (n=266) that completed the survey (n=26), which is a low number for doing statistical analysis. Besides some quantitative questions, students had also the possibility to freely give feedback on the assignments. Both survey types (quantitative answers and qualitative feedback) solely relied on the self-assessment of the students and one might wonder how representative a self-assessment is for evaluating learning outcomes. Both problems (size of the survey and actual achievements of learning outcomes) are getting discussed at the end of the paper, that rightly refers to its results as preliminary. I nevertheless think that this survey can help to better understand the role that video games can play in class. As the author rightly claims, this survey needs to be enhanced with a higher number of participants and a better way of determining the learning outcomes objectively. This paper can serve as a start into how we can determine the senseful use of video games in classrooms and what students think about doing so. References

Stephan, R. (2023). Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics Classroom, Zenodo, 8221286, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8221286

| Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics Classroom | Stephan, Robert | <p>This study assesses student feedback from the implementation of Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey as a teaching tool in a lower level, general education Classics course (CLAS 160B1 - Meet the Ancients: Gateway to Greece and Rome). In this course, which... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Mediterranean | Sebastian Hageneuer | Anonymous, Jeremiah McCall | 2023-08-07 16:45:31 | View |

19 Feb 2024

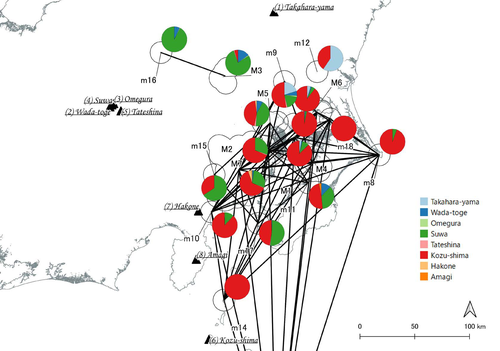

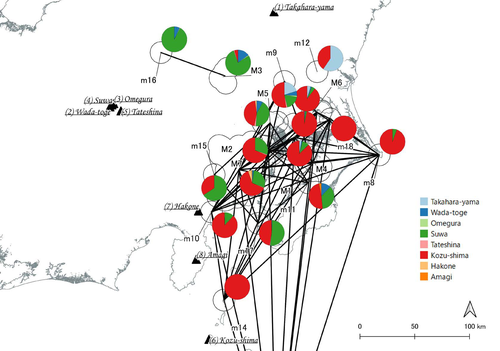

Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias ReductionFumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330Evaluating Methods for Reducing Sampling Bias in Network AnalysisRecommended by James Allison based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer

In a recent article, Fumihiro Sakahira and Hiro'omi Tsumura (2023) used social network analysis methods to analyze change in obsidian trade networks in Japan throughout the 13,000-year-long Jomon period. In the paper recommended here (Sakahira and Tsumura 2024), Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction they revisit that data and describe additional analyses that confirm the robustness of their social network analysis. The data, analysis methods, and substantive conclusions of the two papers overlap; what this new paper adds is a detailed examination of the data and methods, including use of bootstrap analysis to demonstrate the reasonableness of the methods they used to group sites into clusters. Both papers begin with a large dataset of approximately 21,000 artifacts from more than 250 sites dating to various times throughout the Jomon period. The number of sites and artifacts, varying sample sizes from the sites, as well as the length of the Jomon period, make interpretation of the data challenging. To help make the data easier to interpret and reduce problems with small sample sizes from some sites, the authors assign each site to one of five sub-periods, then define spatial clusters of sites within each period using the DBSCAN algorithm. Sites with at least three other sites within 10 km are joined into clusters, while sites that lack enough close neighbors are left as isolates. Clusters or isolated sites with sample sizes smaller than 30 were dropped, and the remaining sites and clusters became the nodes in the networks formed for each period, using cosine similarities of obsidian assemblages to define the strength of ties between clusters and sites. The main substantive result of Sakahira and Tsumura’s analysis is the demonstration that, during the Middle Jomon period (5500-4500 cal BP), clusters and isolated sites were much more connected than before or after that period. This is largely due to extensive distribution of obsidian from the Kozu-shima source, located on a small island off the Japanese mainland. Before the Middle Jomon period, Kozu-shima obsidian was mostly found at sites near the coast, but during the Middle Jomon, a trade network developed that took Kozu-shima obsidian far inland. This ended after the Middle Jomon period, and obsidian networks were less densely connected in the late and last Jomon periods. The methods and conclusions are all previously published (Sakahira and Tsumura 2023). What Sakahira and Tsumura add in Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction are: · an examination of the distribution of cosine similarities between their clusters for each period · a similar evaluation of the cosine similarities within each cluster (and among the unclustered sites) for each period · bootstrap analyses of the mean cosine similarities and network densities for each time period These additional analyses demonstrate that the methods used to cluster sites are reasonable, and that the use of spatially defined clusters as nodes (rather than the individual sites within the clusters) works well as a way of reducing bias from small, unrepresentative samples. An alternative way to reduce that bias would be to simply drop small assemblages, but that would mean ignoring data that could usefully contribute to the analysis. The cosine similarities between clusters show patterns that make sense given the results of the network analysis. The Middle Jomon period has, on average, the highest cosine similarities between clusters, and most cluster pairs have high cosine similarities, consistent with the densely connected, spatially expansive network from that time period. A few cluster pairs in the Middle Jomon have low similarities, apparently representing comparisons including one of the few nodes on the margins on the network that had little or no obsidian from the Kozu-shima source. The other four time periods all show lower average inter-cluster similarities and many cluster pairs have either high or low similarities. This probably reflects the tendency for nearby clusters to have very similar obsidian assemblages to each other and for geographically distant clusters to have dissimilar obsidian assemblages. The pattern is consistent with the less densely connected networks and regionalization shown in the network graphs. Thinking about this pattern makes me want to see a plot of the geographic distances between the clusters against the cosine similarities. There must be a very strong correlation, but it would be interesting to know whether there are any cluster pairs with similarities that deviate markedly from what would be predicted by their geographic separation. The similarities within clusters are also interesting. For each time period, almost every cluster has a higher average (mean and median) within-cluster similarity than the similarity for unclustered sites, with only two exceptions. This is partial validation of the method used for creating the spatial clusters; sites within the clusters are at least more similar to each other than unclustered sites are, suggesting that grouping them this way was reasonable. Although Sakahira and Tsumura say little about it, most clusters show quite a wide range of similarities between the site pairs they contain; average within-cluster similarities are relatively high, but many pairs of sites in most clusters appear to have low similarities (the individual values are not reported, but the pattern is clear in boxplots for the first four periods). There may be value in further exploring the occurrence of low site-to-site similarities within clusters. How often are they caused by small sample sizes? Clusters are retained in the analysis if they have a total of at least 30 artifacts, but clusters may contain sites with even smaller sample sizes, and small samples likely account for many of the low similarity values between sites in the same cluster. But is distance between sites in a cluster also a factor? If the most distant sites within a spatially extensive cluster are dissimilar, subdividing the cluster would likely improve the results. Further exploration of these within-cluster site-to-site similarity values might be worth doing, perhaps by plotting the similarities against the size of the smallest sample included in the comparison, as well as by plotting the cosine similarity against the distance between sites. Any low similarity values not attributable to small sample sizes or geographic distance would surely be worth investigating further. Sakahira and Tsumura also use a bootstrap analysis to simulate, for each time period, mean cosine similarities between clusters and between site pairs without clustering. They also simulate the network density for each time period before and after clustering. These analyses show that, almost always, mean simulated cosine similarities and mean simulated network density are higher after clustering than before. The simulated mean values also match the actual mean values better after clustering than before. This improved match to actual values when the sites are clustered for the bootstrap reinforces the argument that clustering the sites for the network analysis was a reasonable result. The strength of this paper is that Sakahira and Tsumura return to reevaluate their previously published work, which demonstrated strong patterns through time in the nature and extent of Jomon obsidian trade networks. In the current paper they present further analyses demonstrating that several of their methodological decisions were reasonable and their results are robust. The specific clusters formed with the DBSCAN algorithm may or may not be optimal (which would be unreasonable to expect), but the authors present analyses showing that using spatial clusters does improve their network analysis. Clustering reduces problems with small sample sizes from individual sites and simplifies the network graphs by reducing the number of nodes, which makes the results easier to interpret. Reference Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2023). Tipping Points of Ancient Japanese Jomon Trade Networks from Social Network Analyses of Obsidian Artifacts. Frontiers in Physics 10:1015870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.1015870 Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2024). Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction, Zenodo, 10057602, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330 | Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction | Fumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura | <p>This study aims to investigate the dynamics of obsidian trade networks during the Jomon period (approximately 15,000 to 2,400 years ago), the hunting and gathering era in Japan. To improve regional representation and reduce the distortions caus... |  | Asia, Computational archaeology | James Allison | Thegn Ladefoged, Matthew Peeples | 2023-05-28 05:51:12 | View |

28 Feb 2024

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and DutchAlex Brandsen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10610882Multilingual Named Entity Recognition in archaeology: an approach based on deep learningRecommended by Maria Pia di Buono based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch” (Brandsen 2024) explores the use of BERT-based models for Named Entity Recognition (NER) in archaeology across three languages: English, German, and Dutch. It introduces six models trained and fine-tuned on archaeological literature, followed by the presentation and evaluation of three models specifically tailored for NER tasks. The focus on multilingualism enhances the applicability of the research, while the meticulous evaluation using standard metrics demonstrates a rigorous methodology. The introduction of NER for extracting concepts from literature is intriguing, while the provision of a method for others to contribute to BERT model pre-training enhances collaborative research efforts. The innovative use of BERT models to contextualize archaeological data is a notable strength, bridging the gap between digitized information and computational models. Additionally, the paper's release of fine-tuned models and consideration of environmental implications add further value. In summary, the paper contributes significantly to the task of NER in archaeology, filling a crucial gap and providing foundational tools for data mining and reevaluating legacy archaeological materials and archives. Reference Brandsen, A. (2024). Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch. Zenodo, 8296920, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296920 | Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch | Alex Brandsen | <p>This short paper describes a collection of BERT models for the archaeology domain. We took existing language specific BERT models in English, German, and Dutch, and further pre-trained them with archaeology specific training data. We then took ... |  | Computational archaeology | Maria Pia di Buono | 2023-08-29 14:50:21 | View | |

06 Aug 2023

A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional ProjectScott Madry, Gregory Jansen, Seth Murray, Elizabeth Jones, Lia Willcoxon, Ebtihal Alhashem https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7967035A meticulous description of archiving research data from a long-running landscape research projectRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and Iwona DudekThe paper “A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project” (Madry et al., 2023) describes practices, challenges and opportunities encountered in digital archiving of a landscape research project running in Burgundy, France for more than 45 years. As an unusually long-running multi-disciplinary undertaking working with a large variety of multi-modal digital and non-digital data, the Burgundy project has lived through the development of documentation and archiving technologies from the 1970s until today and faced many of the challenges relating to data management, preservation and migration. The major strenght of the paper is that it provides a detailed description of the evolution of digital data archiving practices in the project including considerations about why some approaches were tested and abandoned. This differs from much of the earlier literature where it has been more common to describe individual solutions how digital archiving was either planned or was performed at one point of time. A longitudinal description of what was planned, how and why it has worked or failed so far, as described in the paper, provides important insights in the everyday hurdles and ways forward in digital archiving. As a description of a digital archiving initiative, the paper makes a valuable contribution for the data archiving scholarship as a case description of practices and considerations in one research project. For anyone working with data management in a research project either as a researcher or data manager, the text provides useful advice on important practical matters to consider ahead, during and after the project. The main advice the authors are giving, is to plan and act for data preservation from the beginning of the project rather than doing it afterwards. To succeed in this, it is crucial to be knowledgeable of the key concepts of data management—such as “digital data fixity, redundant backups, paradata, metadata, and appropriate keywords” as the authors underline—including their rationale and practical implications. The paper shows also that when and if unexpected issues raise, it is important to be open for different alternatives, explore ways forward, and in general be flexible. The paper makes also a timely contribution to the discussion started at the session “Archiving information on archaeological practices and work in the digital environment: workflows, paradata and beyond” at the Computer Applications and Quantitative 2023 conference in Amsterdam where it was first presented. It underlines the importance of understanding and communicating the premises and practices of how data was collected (and made) and used in research for successful digital archiving, and the similar pertinence of documenting digital archiving processes to secure the keeping, preservation and effective reuse of digital archives possible. ReferencesMadry, S., Jansen, G., Murray, S., Jones, E., Willcoxon, L. and Alhashem, E. (2023) A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project, Zenodo, 7967035, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7967035 | A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project | Scott Madry, Gregory Jansen, Seth Murray, Elizabeth Jones, Lia Willcoxon, Ebtihal Alhashem | <p>This paper will consider the practical realities that have been encountered while seeking to create a usable Digital Archiving system of a long-term and multi-participant research project. The lead author has been involved in archaeologic... |  | Computational archaeology, Environmental archaeology, Landscape archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-24 18:46:34 | View | |

06 Oct 2023

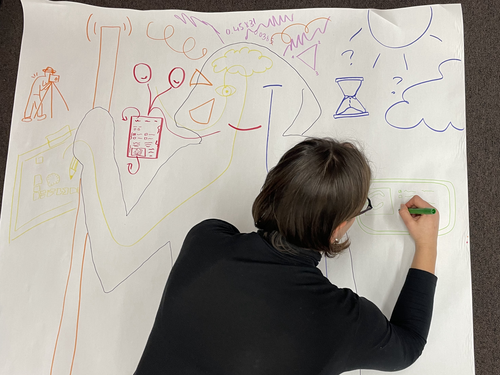

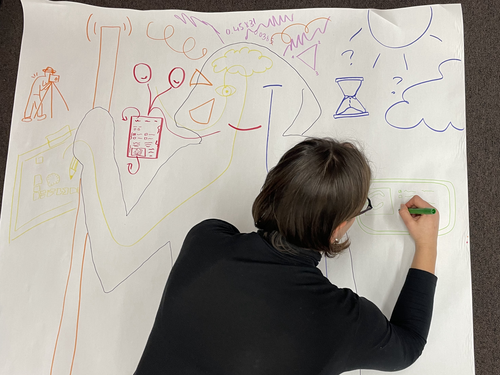

Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice.Araar, Leila; Morgan, Colleen; Fowler, Louise https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7990581Understanding archaeological documentation through a participatory, arts-based approachRecommended by Nicolo Dell'Unto based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThis paper presents the use of a participatory arts-based methodology to understand how digital and analogue tools affect individuals' participation in the process of archaeological recording and interpretation. The preliminary results of this work highlight the importance of rethinking archaeologists' relationship with different recording methods, emphasising the need to recognise the value of both approaches and to adopt a documentation strategy that exploits the strengths of both analogue and digital methods. Although a larger group of participants with broader and more varied experience would have provided a clearer picture of the impact of technology on current archaeological practice, the article makes an important contribution in highlighting the complex and not always easy transition that archaeologists trained in analogue methods are currently experiencing when using digital technology. This is assessed by using arts-based methodologies to enable archaeologists to consider how digital technologies are changing the relationship between mind, body and practice. I found the range of experiences described in the papers by the archaeologists involved in the experiment particularly interesting and very representative of the change in practice that we are all experiencing. As the article notes, the two approaches cannot be directly compared because they offer different possibilities: if analogue methods foster a deeper connection with the archaeological material, digital documentation seems to be perceived as more effective in terms of data capture, information exchange and data sharing (Araar et al., 2023). It seems to me that an important element to consider in such a study is the generational shift and the incredible divide between native and non-native digital. The critical issues highlighted in the paper are central and provide important directions for navigating this ongoing (digital) transition. References Araar, L., Morgan, C. and Fowler, L. (2023) Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice., Zenodo, 7990581, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7990581 | Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice. | Araar, Leila; Morgan, Colleen; Fowler, Louise | <p>This paper uses a participatory, art-based methodology to understand how digital and analog tools impact individuals' experience and perceptions of archaeological recording. Body mapping involves the co-creation of life-sized drawings and narra... |  | Computational archaeology, Theoretical archaeology | Nicolo Dell'Unto | 2023-06-01 09:06:52 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer