Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date▼ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Mar 2024

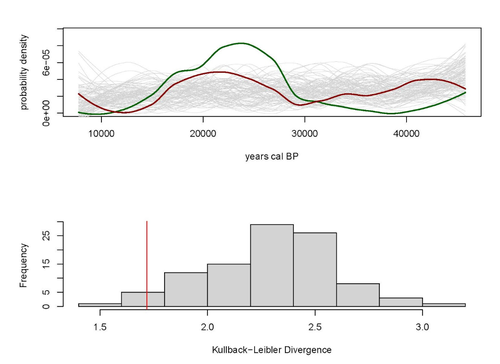

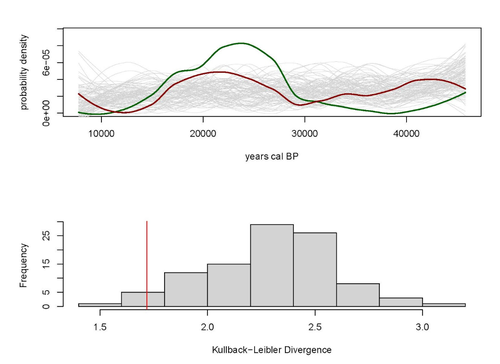

A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasetsNimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733A new approach to Predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer

Various biological systems have been subjected to mathematical modelling to enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions among different species. Among these models, the predator-prey model holds a significant position. Its relevance stems not only from its application in biology, where it largely governs the coexistence of diverse species in open ecosystems, but also from its utility in other domains. Predator-prey dynamics have long been a focal point in population ecology, yet access to real-world data is confined to relatively brief periods, typically less than a century. Studying predator-prey dynamics over extended periods presents challenges due to the limited availability of population data spanning more than a century. The most extensive dataset is the hare-lynx records from the Hudson Bay Company, documenting a century of fur trade [1]. However, other records are considerably shorter, usually spanning decades [2,3]. This constraint hampers our capacity to investigate predator-prey interactions over centennial or millennial scales. Marom and Wolkowski [4] propose here that leveraging regional radiocarbon databases offers a solution to this challenge, enabling the reconstruction of predator-prey population dynamics over extensive timeframes. To substantiate this proposition, they draw upon examples from Pleistocene Beringia and the Holocene Judean Desert. This approach is highly relevant and might provide insight into ecological processes occurring at a time scale beyond the limits of current ecological datasets. The methodological approach employed in this article proposes that the summed probability distribution (SPD) of predator radiocarbon dates, which reflects changes in population size, will demonstrate either more or less variation than anticipated from random sampling in a homogeneous distribution spanning the same timeframe. A deviation from randomness would imply a covariation between predator and prey populations. This basic hypothesis makes no assumptions about the frequency, mechanism, or cause of predator-prey interactions, as it is assumed that such aspects cannot be adequately tested with the available data. If validated, this hypothesis would offer initial support for the idea that long-term regional radiocarbon data contain signals of predator-prey interactions. This approach could justify the construction of larger datasets to facilitate a more comprehensive exploration of these signal structures.

References [1] Elton, C. and Nicholson, M., 1942. The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada. J. Anim. Ecol. 11, 215–244. [2] Gilg, O., Sittler, B. and Hanski, I., 2009. Climate change and cyclic predator-prey population dynamics in the high Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01927.x [3] Vucetich, J.A., Hebblewhite, M., Smith, D.W. and Peterson, R.O., 2011. Predicting prey population dynamics from kill rate, predation rate and predator-prey ratios in three wolf-ungulate systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01855.x [4] Marom, N. and Wolkowski, U. (2024). A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets, BioRxiv, 566733, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733 | A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets | Nimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski | <p>Predator-prey interactions have been a central theme in population ecology for the past century, but real-world data sets only exist for recent, relatively short (<100 years) time spans. This limits our ability to study centennial/millennial... |  | Bioarchaeology, Environmental archaeology, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | 2023-12-12 14:37:22 | View | |

20 Feb 2024

Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of ArchaeologyWaagen, Jitte & Wijngaarden, Gert Jan van https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10061343Rewriting Archaeological Narratives: Archaeology of Archaeology through 3D Site Topography RecordingRecommended by Devi Taelman based on reviews by Geert Verhoeven, Jesús García-Sánchez and Catherine Scott based on reviews by Geert Verhoeven, Jesús García-Sánchez and Catherine Scott

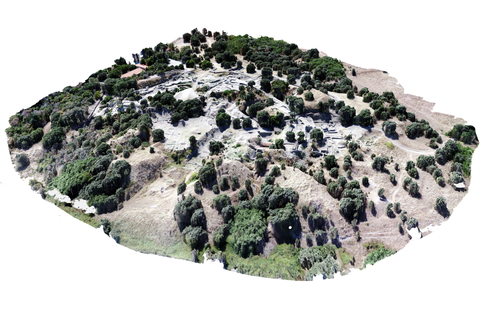

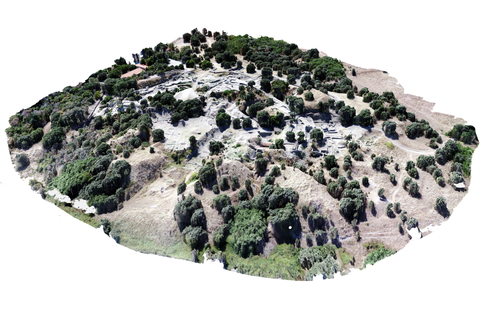

Even though applications of 3D recording have existed in archaeology for a long time, it is only since the early 2000s that this field of research has become mainstream thanks to technological advances, and the availability of low-cost sensors and image-based modelling software. This has led to significant changes in the way archaeological sites are documented. This paper entitled "Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology" by Jitte Waagen & Gert Jan van Wijngaarden (2024) presents an overview of the current developments in the application possibilities of 3D site topography recording in archaeology. The paper is the result of the round table discussion "Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology" at the CAA conference on 5 April 2023 in Amsterdam, with contributions from Radu Brunchi, Nicola Lercari, Joep Orbons, Davide Tanasi, Alicia Walsh, Pawel Wolf and Teagan Zoldoske. The paper starts with a discussion of the Amsterdam Troy Project (ATP). In the frame of the ATP, the rich history of archaeological activity (over 150 years of fieldwork) at Troy is being studied to explore how previous archaeological research has helped to shape the current topography of the site and how these earlier research activities, embedded in their contemporary theoretical frameworks, have determined our understanding of the site (see Murray and M. Spriggs 2017, Carver 2011 for the influence of theory on archaeological fieldwork and archaeology as a discipline), the so-called 'Archaeology of Archaeology' approach. In addition to studying previous research records and re-excavating old excavation trenches, a central element of the project is the 3D recording of the past and present topography of the site in order to reconstruct the archaeological research activities at the site and their impact on the archaeological landscape. The paper focuses on current trends in 3D recording of archaeological site topography and discusses three main areas where 3D recording of archaeological site topography can contribute to the "Archaeology of Archaeology" approach: (1) monitoring the topography of sites for preservation, conservation, research and dissemination purposes; (2) reconstructing, reevaluating and reinterpreting past archaeological research efforts; and (3) archiving in a 4D (GIS) environment. This is done using the example of the Amsterdam Troy project and comparing it with other projects using similar methods and approaches. Using these case studies, the authors effectively discuss the impact of these technologies on the understanding of the topography of archaeological sites and how 3D recording can enhance archaeological research methodologies and interpretations, for example, by not using such 3D approaches as a stand-alone product but integrating them with available information from previous research activities. They also recognise the limitations and challenges involved, such as the need for customised data acquisition strategies and the lack of ready-made software solutions for developing comprehensive data management strategies. One topic that could have been covered in more detail is how 3D site topography recording (and 3D recording in general) is affected by current theoretical developments in archaeology. Like any other archaeological fieldwork or data collection approach, it is a child of its time. Decisions such as what to record, how to record, what to store, how to store, what to visualise, and how to visualise influence our understanding of archaeological sites (Ward 2022). This minor critical reflection aside, the paper makes a timely and significant contribution to archaeology by addressing current trends and the limitations of the increasingly widespread use of 3D site topography recording technologies. References Carver, G. (2011). Reflections on the archaeology of archaeological excavation, Archaeological Dialogues 18(1), pp. 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203811000067 Murray, T. and Spriggs, M. (2017). The historiography of archaeology: exploring theory, contingency and rationality, World Archaeology 49(2), pp. 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2017.1334583 Ward, C. (2022). Excavating the Archive / Archiving the Excavation: Archival Processes and Contexts in Archaeology, Advances in Archaeological Practice 10(2), pp. 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2022.1 Waagen, J. and van Wijngaarden, G.J. (2024). Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology, Zenodo, 10061343, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommonded by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10061343 | Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology | Waagen, Jitte & Wijngaarden, Gert Jan van | <p>The current ubiquitous use of 3D recording technologies in archaeological fieldwork, for a large part due to the application of budget-friendly (drone) sensors and the availability of many low-cost image-based 3D modelling software packages, ha... |  | Computational archaeology, Remote sensing | Devi Taelman | 2023-10-17 23:03:47 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

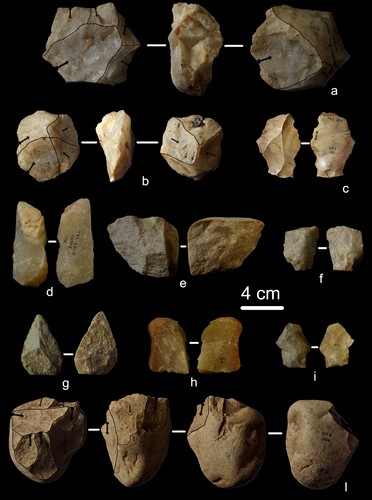

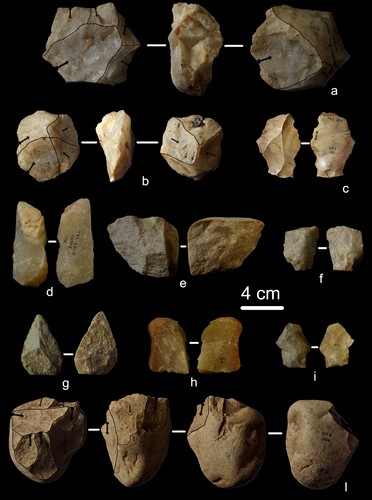

First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy)Sara Daffara, Carlo Giraudi, Gabriele L.F. Berruti, Sandro Caracausi, Francesca Garanzini https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4ufNot Simply the Surface: Manifesting Meaning in What Lies Above.Recommended by Marcel Kornfeld based on reviews by Lawrence Todd, Jason LaBelle and 2 anonymous reviewersThe archaeological record comes in many forms. Some, such as buried sites from volcanic eruptions or other abrupt sedimentary phenomena are perhaps the only ones that leave relatively clean snapshots of moments in the past. And even in those cases time is compressed. Much, if not all other archaeological record is a messy affair. Things, whatever those things may be, artifacts or construction works (i.e., features), moved, modified, destroyed, warped and in a myriad of ways modified from their behavioral contexts. Do we at some point say the record is worthless? Not worth the effort or continuing investigation. Perhaps sometimes this may be justified, but as Daffara and colleagues show, heavily impacted archaeological remains can give us clues and important information about the past. Thoughtful and careful prehistorians can make significant contributions from what appear to be poor archaeological records. In the case of Daffara and colleagues, a number of important theoretical cross-sections can be recognized. For a long time surface archaeology was thought of simply as a way of getting a preliminary peak at the subsurface. From some of the earliest professional archaeologists (e.g., Kidder 1924, 1931; Nelson 1916) to the New Archaeologists of the 1960s, the link between the surface and subsurface was only improved in precision and systematization (Binford et al. 1970). However, at Hatchery West Binford and colleagues not only showed that surface material can be used more reliably to get at the subsurface, but that substantive behavioral inferences can be made with the archaeological record visible on the surface. Much more important are the behavioral implications drawn from surface material. I am not sure we can cite the first attempts at interpreting prehistory from the surface manifestations of the archaeological record, but a flurry of such approaches proliferated in the 1970s and beyond (Dunnell and Dancey 1983; Ebert 1992; Foley 1981). Off-site archaeology, non-site archaeology, later morphing into landscape archaeology all deal strictly with surface archaeological record to aid in understanding the past. With the current paper, Daffara and colleagues (2024) are clearly in this camp. Although still not widely accepted, it is clear that some behaviors (parts of systems) can only be approached from surface archaeological record. It is very unlikely that a future archaeologist will be able to excavate an entire human social/cultural system; people moving from season to season, creating multiple long and short term camps, travelling, procuring resources, etc. To excavate an entire system one would need to excavate 20,000 km2 or some similarly impossible task. Even if it was physically possible to excavate such an enormous area, it is very likely that some of contextual elements of any such system will be surface manifestations. Without belaboring the point, surface archaeological record yields data like any other archaeological record. We must contextual the archaeological artifacts or features weather they come from surface or below. Daffara and colleagues show us that we can learn about deep prehistory of northern Italy, with collections that were unsystematically collected, biased by agricultural as well as other land deformations agents. They carefully describe the regional prehistory as we know it, in particular specific well documented sites and assemblages as a means of applying such knowledge to less well controlled or uncontrolled collections.

References Binford, L., Binford, R. S. R., Whallon, R. and Hardin, M. A. (1970). Archaeology of Hatchery West. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, No. 24, Washington D.C. Daffara, S., Giraudi, C., Berruti, G. L. F., Caracausi, S. and Garanzini, F. (2024). First evidence of a Palaeolithic frequentation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy), OSF Preprints, pz4uf, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4uf Dunnell, R. C. and Dancey, W. S. (1983). The siteless survey: a regional scale data collection strategy. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 6, edited by Michael B. Schiffer, pp. 267-287. Academic Press, New York. Ebert, J. I. (1992). Distributional Archaeology. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. Foley, R. A. (1981). Off site archaeology and human adaptation in eastern Africa: An analysis of regional artefact density in the Amboseli, Southern Kenya. British Archaeological Reports International Series 97. Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 3. Oxford England. Kidder, A. V. (1924). An Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology, With a Preliminary Account of the Excavations at Pecos. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy, no. 1. New Haven, Connecticut. Kidder, A. V. (1931). The Pottery of Pecos, vol. 1. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy. New Haven, Connecticut. Nelson, N. (1916). Chronology of the Tano Ruins, New Mexico. American Anthropologist 18(2):159-180. | First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy) | Sara Daffara, Carlo Giraudi, Gabriele L.F. Berruti, Sandro Caracausi, Francesca Garanzini | <p>The Trino hill is an isolated relief located in north-western Italy, close to Trino municipality. The hill was subject of multidisciplinary studies during the 1970s, when, because of quarrying and agricultural activities, five concentrations of... |  | Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic | Marcel Kornfeld | 2023-10-04 16:58:19 | View | |

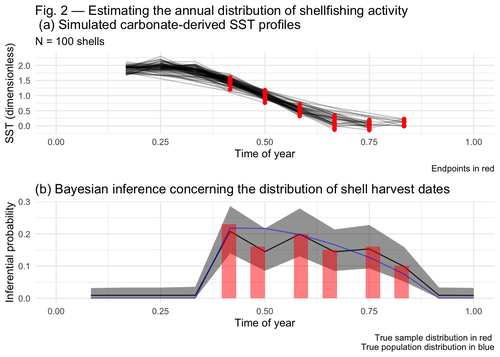

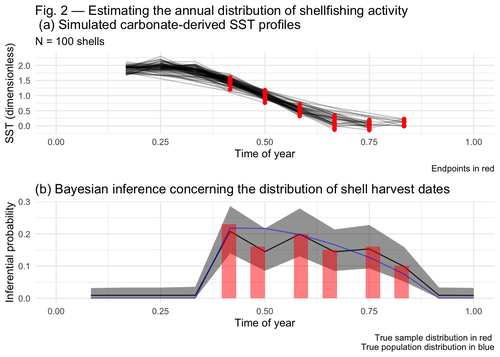

26 Mar 2024

Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approachJordan Brown and Gabriel Lewis https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7949547Mixture models and seasonal mobilityRecommended by Alfredo Cortell-Nicolau and Simon Carrignon based on reviews by Iza Romanowska and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper by Brown & Lewis [1] presents an approach to measure seasonal mobility and subsistence practices. In order to do so, the paper proposes a Bayesian mixture model to estimate the annual distribution of shellfish harvesting activity. Following the recommendations of the two reviewers, the paper presents a clear and innovative method to assess seasonal mobility for prehistoric groups, although it could benefit from additional references regarding isotopic literature. While the adequacy of isotope analysis for estimating mobility patterns in Archaeology has been extensively proven by now, work on specific seasonal mobility is not that much abundant. However, this is a key issue, since seasonal mobility is one of the main social components defining the differences between groups both considering farming vs hunting and gathering or even among hunter-gatherer groups themselves. In this regard, the paper brings a valuable methodological resources that can be used for further research in this issue. One of its greatest values is the fact that it can quantify the uncertainty present in previous isotope studies in seasonal mobility. As stated by the authors, the model can still undergo several optimisation aspects, but as it stands, it is already providing a valuable asset regarding the quantification of uncertainy in the isotopic studies of seasonal mobility. Reference [1] Brown, J. and Lewis, G. (2024). Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approach. Zenodo, 7949547, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7949547 | Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approach | Jordan Brown and Gabriel Lewis | <p>The problem of accurately and reliably estimating the annual distribution of seasonally-varying human settlement and subsistence practices is a classic concern among archaeologists, which has only become more relevant with the increasing import... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology, Environmental archaeology, North America, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Alfredo Cortell-Nicolau | Iza Romanowska, Eduardo Herrera Malatesta, Alejandro Sierra Sainz-Aja, Sam Leggett, Christianne Fernee, Anonymous, Asier García-Escárzaga , Paul Szpak , Maria Elena Castiello , Jasmine Lundy , Tansy Branscombe | 2023-10-03 04:45:54 | View |

08 Jan 2024

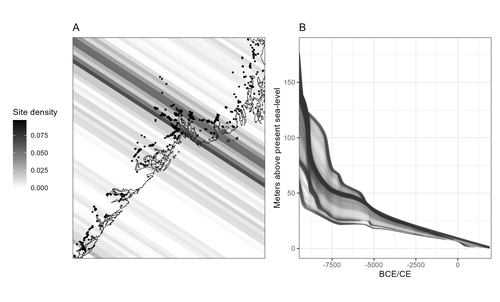

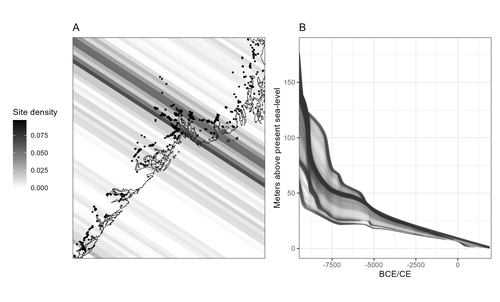

Comparing summed probability distributions of shoreline and radiocarbon dates from the Mesolithic Skagerrak coast of NorwayIsak Roalkvam, Steinar Solheim https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/2f8ph/Taking the Reverend Bayes to the seaside: Improving Norwegian Mesolithic shoreline dating with advanced statistical approachesRecommended by Felix Riede based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper entitled “Comparing summed probability distributions of shoreline and radiocarbon dates from the Mesolithic Skagerrak coast of Norway” by Isak Roalkvam and Steinar Solheim (2024) sheds new light on the degree to which shoreline dating may be used as a reliable chronological and palaeodemographic proxy in the Mesolthic of southern Norway. Based on geologically motivated investigations of eustatic and isostatic sea-level changes, shoreline dating has long been used as a method to date archaeological sites in Scandinavia, not least in Norway (e.g., Bjerck 2008; Astrup 2018). Establishing reliable sea-level curves requires much effort and variations across regions may be substantial. While this topic has seen a great deal of attention in Norway specifically, many purely geological questions remain. In addition, dating archaeological sites by linking their elevation to previously established seal-level curves relies strongly on the foundational assumption that such sites were in fact shore-bound. Given the strong contrast between terrestrial and marine productivity in high-latitude regions such as Norway, this assumption per se is not unreasonable. It is very likely that the sea has played a decisive role in the lives of Stone Age peoples throughout (Persson et al. 2017), just as it has in later periods here. However, many confounding factors relating to both taphonomy and human behaviour are also likely to have loosened the shore/site relationship. Systematic variations driven by cultural norms about settlement location, mobility, as well as factors such as shelter construction, fuel use and a range of other possible factors could variously have impacted the validity or at least the precision of shoreline dating. By developing a new methodology for handling and assessing a large number of shoreline dated sites, Roalkvam and Solheim use state-of-the-art Bayesian statistical methods to compare shoreline and radiocarbon dates as proxies for population activity. The probabilistic treatment of shoreline dates in this way is novel, and the divergences between the two data sets are interpreted by the authors in light of specific behavioural, cultural, and demographic changes. Many of the peaks and troughs observed in these time-series may be interpreted in light of long-observed cultural transitions while others may relate to population dynamics now also visible in palaeogenomic analyses (Günther et al. 2018; Manninen et al. 2021). Overall, this paper makes an innovative and fresh contribution to the use of shoreline dating in Norwegian archaeology, specifically by articulating it with recent developments in Open Science and data-driven approaches to archaeological questions (Marwick et al. 2017). References Astrup, P. M. 2018. Sea-Level Change in Mesolithic Southern Scandinavia : Long- and Short-Term Effects on Society and the Environment. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. Bjerck, H. B. 2008. Norwegian Mesolithic Trends: A Review. In Mesolithic Europe, edited by Geoff Bailey and Penny Spikins, 60–106. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Günther, T., Malmström, H., Svensson, E. M., Omrak, A., Sánchez-Quinto, F., Kılınç, G. M., Krzewińska, M. et al. 2018. Population Genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating Early Postglacial Migration Routes and High-Latitude Adaptation. PLOS Biology 16 (1): e2003703. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703 Manninen, M. A., Damlien, H., Kleppe, J. I., Knutsson, K., Murashkin, A., Niemi, A. R., Rosenvinge, C. S. and Persson, P. 2021. First Encounters in the North: Cultural Diversity and Gene Flow in Early Mesolithic Scandinavia. Antiquity 95 (380): 310–28. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.252 Marwick, B., d’Alpoim Guedes, J. A., Barton, C. M., Bates, L. A., Baxter, M., Bevan, A., Bollwerk, E. A. et al. 2017. Open Science in Archaeology. The SAA Archaeological Record 17 (4): 8–14. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/72n8g Persson, P., Riede, F., Skar, B., Breivik, H. M. and Jonsson, L. 2017. The Ecology of Early Settlement in Northern Europe: Conditions for Subsistence and Survival. Sheffield: Equinox. Roalkvam, I. and Solheim, S. (2024). Comparing summed probability distributions of shoreline and radiocarbon dates from the Mesolithic Skagerrak coast of Norway, SocArXiv, 2f8ph, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/2f8ph | Comparing summed probability distributions of shoreline and radiocarbon dates from the Mesolithic Skagerrak coast of Norway | Isak Roalkvam, Steinar Solheim | <p>By developing a new methodology for handling and assessing a large number of shoreline dated sites, this paper compares the summed probability distribution of radiocarbon dates and shoreline dates along the Skagerrak coast of south-eastern Norw... |  | Computational archaeology, Dating, Europe, Mesolithic, Paleoenvironment | Felix Riede | 2023-09-26 16:43:29 | View | |

08 Apr 2024

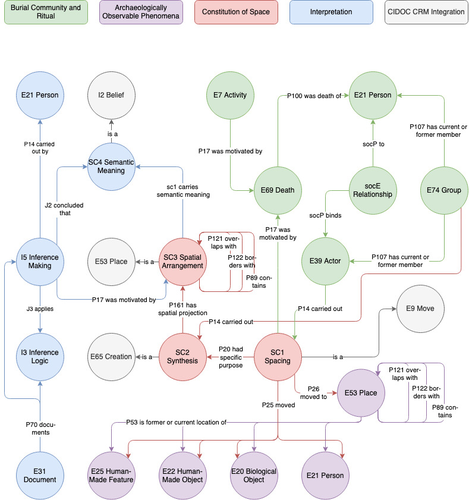

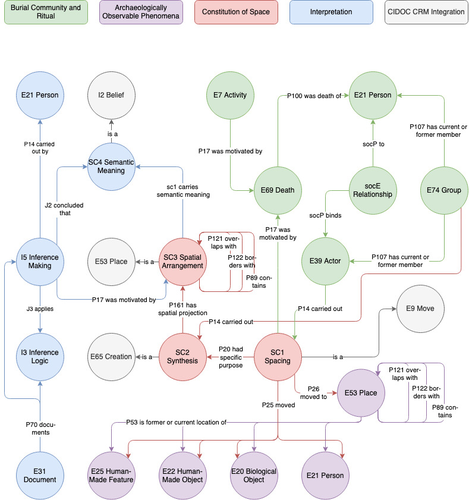

Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contextsAline Deicke https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8310170A new approach to a data ontology for the qualitative assessment of funerary spacesRecommended by Asuman Lätzer-Lasar based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The paper by Aline Deicke [1] is very readable, and it succeeds in presenting a still unnoticed topic in a well-structured way. It addresses the topic of “how to model social-spatial relations in antiquity”, as the title concisely implies, and makes important and interesting points about their interrelationship by drawing on latest theories of sociologists such as Martina Löw combined with digital tools, such as the CIDOC CRM-modeling. The author provides an introductory insight into the research history of funerary archaeology and addresses the problematic issue of not having investigated fully the placement of entities of the grave inventory. So far, the focus of the analysis has been on the composition of the assemblage and not on the positioning within this space-and time-limited context. However, the positioning of the various entities within the burial context also reveals information about the objects themselves, their value and function, as well as about the world view and intentions of the living and dead people involved in the burial. To obtain this form of qualitative data, the author suggests modeling knowledge networks using the CIDOC CRM. The method allows to integrate the spatial turn combined with aspects of the actor-network-theory. The theoretical backbone of the contribution is the fundamental scholarship of Martina Löw’s “Raumsoziologie” (sociology of space), especially two categories of action namely placing and spacing (SC1). The distinction between the two types of action enables an interpretative process that aims for the detection of meaningfulness behind the creation process (deposition process) and the establishment of spatial arrangement (find context). To illustrate with a case study, the author discusses elite burial sites from the Late Urnfield Period covering a region north of the Alps that stretches from the East of France to the entrance of the Carpathian Basin. With the integration of very basic spatial relations, such as “next to”, “above”, “under” and qualitative differentiations, for instance between iron and bronze knives, the author detects specific patterns of relations: bronze knives for food preparing (ritual activities at the burial site), iron knives associated with the body (personal accoutrement). The complexity of the knowledge engineering requires the gathering of several CIDOC CRM extensions, such as CRMgeo, CRMarchaeo, CRMba, CRMinf and finally CRMsoc, the author rightfully suggests. In the end, the author outlines a path that can be used to create this kind of data model as the basis for a graph database, which then enables a further analysis of relationships between the entities in a next step. Since this is only a preliminary outlook, no corrections or alterations are needed. The article is an important step in advancing digital archaeology for qualitative research. References [1] Deicke, A. (2024). Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contexts. Zenodo, 8310170, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8310170 | Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contexts | Aline Deicke | <p>Burials have long been one of the most important sources of archaeology, especially when studying past social practices and structure. Unlike archaeological finds from settlements, objects from graves can be assumed to have been placed there fo... |  | Computational archaeology, Protohistory, Spatial analysis, Theoretical archaeology | Asuman Lätzer-Lasar | 2023-09-01 23:15:41 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3DFlorian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269A valuable contribution to automated analysis of palaeolithic artefactsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper (Linsel/Bullenkamp/Mara 2024), the authors propose an automatic system for scar-ridge-pattern detection on palaeolithic artefacts based on Morse Theory. Scare-Ridge pattern recognition is a process that is usually done manually while creating a drawing of the object itself. Automatic systems to detect scars or ridges exist, but only a small amount of them is utilizing 3D data. In addition to the scar-ridges detection, the authors also experiment in automatically detecting the operational sequence, the temporal relation between scars and ridges. As a result, they can export a traditional drawing as well as graph models displaying the relationships between the scars and ridges. After an introduction to the project and the practice of documenting palaeolithic artefacts, the authors explain their procedure in automatising the analysis of scars and ridges as well as their temporal relation to each other on these artefacts. To illustrate the process, an open dataset of lithic artefacts from the Grotta di Fumane, Italy, was used and 62 artefacts selected. To establish a Ground Truth, the artefacts were first annotated manually. The authors then continue to explain in detail each step of the automated process that follows and the results obtained. In the second part of the paper, the results are presented. First the results of the segmentation process shows that the average percentage of correctly labelled vertices is over 91%, which is a remarkable result. The graph modelling however shows some more difficulties, which the authors are aware of. To enhance the process, the authors rightfully aim to include datasets of experimental archaeology in the future. They also aim to develop a way of detecting the operational sequence automatically and precisely. This paper has great potential as it showcases exactly what Digital and Computational Archaeology is about: The development of new digital methods to enhance the analysis of archaeological data. While this procedure is still in development, the authors were able to present a valuable contribution to the automatization of analytical archaeology. By creating a step towards the machine-readability of this data, they also open up the way to further steps in machine learning within Archaeology. BibliographyLinsel, F., Bullenkamp, J. P., and Mara, H. (2024). Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D, Zenodo, 8296269, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269 | Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D | Florian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara | <p>Motivated by the concept of combining the archaeological practice of creating lithic artifact drawings with the potential of 3D mesh data, our goal in this project is not only to analyze the shape at the artifact level, but also to enable a mor... | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Upper Palaeolithic | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-09-01 23:03:59 | View | ||

03 Feb 2024

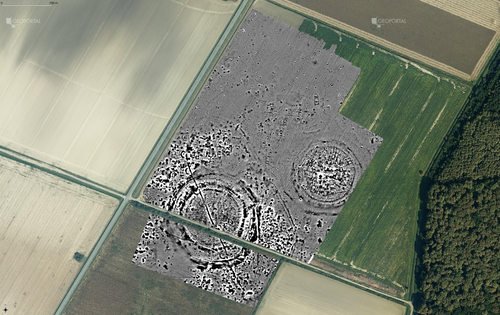

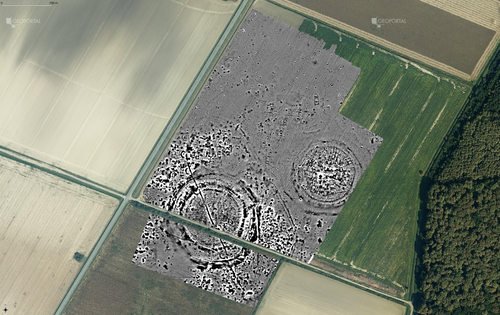

Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern CroatiaSosic Klindzic Rajna; Vuković Miroslav; Kalafatić Hrvoje; Šiljeg Bartul https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970703What lies on top lies also beneath? Connecting crop surface modelling to buried archaeology mapping.Recommended by Markos Katsianis based on reviews by Ian Moffat and Geert Verhoeven based on reviews by Ian Moffat and Geert Verhoeven

This paper (Sosic et al. 2024) explores the Neolithic landscape of the Sopot culture in Đakovština, Eastern Slavonija, revealing a network of settlements through a multi-faceted approach that combines aerial archaeology, magnetometry, excavation, and field survey. This strategy facilitates scalable research tailored to the particularities of each site and allows for improved representations of buried archaeology with minimal intrusion. Using the site of Tomašanci-Dubrava as an example of the overall approach, the study further explores the use of drone imagery for 3D surface modeling, revealing a consistent correlation between crop surface elevation during full plant growth and ground terrain after ploughing, attributed to subsurface archaeological features. Results are correlated with magnetic survey and test-pitting data to validate the micro-topography and clarify the relationship between different subsurface structures. The results obtained are presented in a comprehensive way, including their source data, and are contextualized in relation to conventional cropmark detection approaches and expectations. I found this aspect very interesting, since the crop surface and terrain models contradict typical or textbook examples of cropmark detection, where the vegetation is projected to appear higher in ditches and lower in areas with buried archaeology (Renfrew & Bahn 2016, 82). Regardless, the findings suggest the potential for broader applications of crop surface or canopy height modelling in landscape wide surveys, utilizing ALS data or aerial photographs. It seems then that the authors make a valid argument for a layered approach in landscape-based site detection, where aerial imagery can be used to accurately map the topography of areas of interest, which can then be further examined at site scale using more demanding methods, such as geophysical survey and excavation. This scalability enhances the research's relevance in broader archaeological and geographical contexts and renders it a useful example in site detection and landscape-scale mapping. References Renfrew, C. and Bahn, P. (2016). Archaeology: theories, methods and practice. Thames and Hudson. Sosic Klindzic, R., Vuković, M., Kalafatić, H. and Šiljeg, B. (2024). Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern Croatia, Zenodo, 7970703, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970703 | Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern Croatia | Sosic Klindzic Rajna; Vuković Miroslav; Kalafatić Hrvoje; Šiljeg Bartul | <p>This paper presents the results of a study on the neolithic landscape of the Sopot culture in the area of Đakovština in Eastern Slavonija. A vast network of settlements was uncovered using aerial archaeology, which was further confirmed and chr... |  | Landscape archaeology, Neolithic, Remote sensing, Spatial analysis | Markos Katsianis | 2023-09-01 12:57:04 | View | |

02 Apr 2024

The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial CommunityAlphaeus Lien-Talks https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307882A nice project looking at under-represented demographicRecommended by Alexis Pantos based on reviews by Catriona Cooper and Steinar Kristensen based on reviews by Catriona Cooper and Steinar Kristensen

The paper by A. Lien-Talks [1] presents a small project looking at the use of crowd sourced data collection and particpatory GIS. In particular it looks at the potential of these tools in response to socially disruptive and isolating events such as the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the potential role of digitially mediated heritage initiatives in tackling some of the challenges of changing demographics and life styles. The types of technologies employed are relatively mature, the project identifies potential for such approaches to be used within the local-history/local community settings, though is also a reminer that depsite the much broader adoption of technology within all areas of society than even a few years ago many barriers still remain. While the the sample size and data collected in the project is relatively modest, the focus on empathy toward the intended audiences from the design process, as well as some of the qualitative feedback reported serve as a reminder that participatory, or crowd-sourced data collection initiatives in heritage can, and perhaps should place potential social benefit before data-acquisition of objectives. The project also presents a demographic that is not often represented within the literature and the publication and as such the publication of the article represents a meaningful contribution to ongoing discussions of the role heritage and digitally mediated community archaeology can play a role in developing our societies. References [1] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial Community. Zenodo, 8307882, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307882 | The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial Community | Alphaeus Lien-Talks | <p>Background:<br>As the world becomes increasingly digital, so too must the way in which archaeologists engage with the public. This was particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic, and many outreach and engagement efforts began to move o... |  | Computational archaeology | Alexis Pantos | 2023-09-01 11:25:54 | View | |

24 Jan 2024

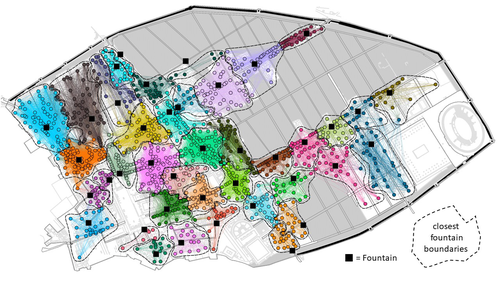

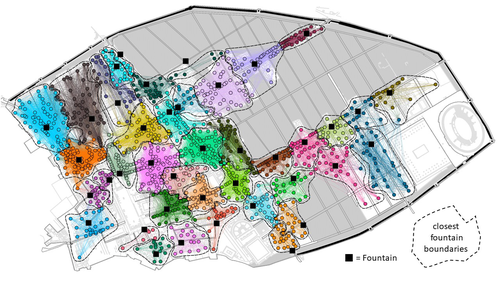

Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in PompeiiNotarian, Matthew https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305968A Valuable Contribution to Archaeological Network Research: A Case Study of PompeiiRecommended by David Laguna-Palma based on reviews by Matthew Peeples, Isaac Ullah and Philip Verhagen based on reviews by Matthew Peeples, Isaac Ullah and Philip Verhagen

The paper entitled 'Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii' [1] presents a significant contribution to the field of archaeological network research, particularly in the challenging task of identifying urban neighborhoods within the context of Pompeii. This study focuses on the relational dynamics within urban neighborhoods and examines their indistinct boundaries through advanced analytical methods. The methodology employed provides a comprehensive analysis of community detection, including the Louvain and Leiden algorithms, and introduces a novel Convex Hull of Admissible Modularity Partitions (CHAMP) algorithm. The incorporation of a network approach into this domain is both innovative and timely. The potential impact of this research is substantial, offering new perspectives and analytical tools. This opens new avenues for understanding social structures in ancient urban settings, which can be applied to other archaeological contexts beyond Pompeii. Moreover, the manuscript is not only methodologically solid but also well-written and structured, making complex concepts accessible to a broad audience. In conclusion, this study represents a valuable contribution to the field of archaeology, particularly for archaeological network research. Their results not only enhance our knowledge of Pompeii but also provide a robust framework for future studies in similar historical contexts. Therefore, this publication advances our understanding of social dynamics in historical urban environments. The rigorous analysis, combined with the innovative application of network algorithms, makes this study a noteworthy addition to the existing body of network science literature. It is recommended for a wide range of scholars interested in the intersection of archaeology, history, and network science. Reference [1] Notarian, Matthew. 2024. Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305968 | Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii | Notarian, Matthew | <p>The definition and identification of urban neighbourhoods in archaeological contexts remain complex and problematic, both theoretically and empirically. As constructs with both social and spatial characteristics, their detection through materia... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Computational archaeology, Mediterranean | David Laguna-Palma | 2023-08-31 19:28:35 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer