and Shumon Tobias Hussain

and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova

based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova

The paper entitled “From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions” submitted by Frederic Auth and colleagues discusses how those rich and often meticulously illustrated catalogues of particular find classes that exist in many corners of archaeology can be brought to the cutting edge of contemporary research through digitisation. This paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology, taxonomy, classification theory, and computational approaches in archaeology.

Auth et al. (2023) begin with outlining the useful notion of the ‘thing-edition’ originally coined by Kerstin Hofmann in the context of her work with the many massive corpora of finds that have characterised, in particular, earlier archaeological knowledge production in Germany (Hofmann et al. 2019; Hofmann 2018). This work critically examines changing trends in the typological characterisation and recording of various find categories, their theoretical foundations or lack thereof and their legacy on contemporary practice. The present contribution focuses on what happens with such corpora when they are integrated into digitisation projects, specifically the efforts by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), the so-called iDAI.world and in regard to two Roman-era material culture groups, the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum (Roman finds from beyond the empire’s borders in eight printed volumes covering thousands of finds of various categories), and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae (Roman plain ware).

Drawing on Bruno Latour’s (2005) actor-network theory (ANT), Auth et al. discuss and reflect on the challenges met and choices to be made when thing-editions are to be transformed into readily accessible data, that is as linked to open, usable data. The intellectual and infrastructural workload involved in such digitisation projects is not to be underestimated. Here, the contribution by Auth et al. excels in the manner that it does not present the finished product – the fully digitised corpora – but instead offers a glimpse ‘under the hood’ of the digitisation process as an interaction between analogue corpus, research team, and the technologies at hand. These aspects were rarely addressed in the literature, rooted in the 1970s early work (Borillo and Gardin 1974; Gaines 1981), on archaeological computerised databases, focused on technical dimensions (see Rösler 2016 for an exception). Their paper can so also be read in the broader context of heterogeneous computer-assisted knowledge ecologies and ‘mangles of practice’ (see Pickering and Guzik 2009) in which practitioners and technological structures respond to each other’s needs and attempt to cooperate in creative ways. As such, Auth et al.’s considerations not least offer valuable resources for Science and Technology Studies-inspired discussions on the cross-fertilization of archaeological theory, practice and currently emerging material and virtual research infrastructures and can be read in conjunction to Gavin Lucas’ (2022) paper on ‘machine epistemology’ due to appear in the same volume.

Perhaps more importantly, however, the work by Auth and colleagues (2023) exemplifies the due diligence required in not merely turning a catalogue from paper to digital document but in transforming such catalogues into long-lasting and patently usable repositories of generations of scholars to come. Deploying the Latourian notions of trade-off and recursive reference, Auth et al. first examine the structure, strengths, and weakness of the two corpora before moving on to showing how the freshly digitised versions offer new and alternative ways of analysing the archaeological material at hand, notably through immediate visualisation opportunities, through ceramic form combinations, and relational network diagrams based on the data inherent in the respective thing-editions.

Catalogues including basic descriptions and artefact illustrations exist for most if not all archaeological periods. They constitute an essential backbone of archaeological work as repeated access to primary material is impractical if not impossible. The catalogues addressed by Auth et al. themselves reflect major efforts on behalf of archaeological experts to arrive at clear and operational classifications in a pre-computerised era. The continued and expanded efforts by Auth and colleagues build on these works and clearly demonstrate the enormous analytical potential to make such data not merely more accessible but also more flexibly interoperable. Their paper will therefore be an important reference for future work with similar ambitions facing similar challenges.

References

Auth, Frederic, Katja Rösler, Wenke Domscheit, and Kerstin P. Hofmann. 2023. “From Paper to Byte: A Workshop Report on the Digital Transformation of Two Thing Editions.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8214563

Borillo, Mario, and Jean-Claude Gardin. 1974. Les Banques de Données Archéologiques. Marseille: Éditions du CNRS.

Gaines, Sylvia W., ed. 1981. Data Bank Applications in Archaeology. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Hofmann, Kerstin P. 2018. “Dingidentitäten Und Objekttransformationen. Einige Überlegungen Zur Edition von Archäologischen Funden.” In Objektepistemologien. Zum Verhältnis von Dingen Und Wissen, edited by Markus Hilgert, Kerstin P. Hofmann, and Henrike Simon, 179–215. Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 59. Berlin: Edition Topoi. https://dx.doi.org/10.17171/3-59

Hofmann, Kerstin P., Susanne Grunwald, Franziska Lang, Ulrike Peter, Katja Rösler, Louise Rokohl, Stefan Schreiber, Karsten Tolle, and David Wigg-Wolf. 2019. “Ding-Editionen. Vom Archäologischen (Be-)Fund Übers Corpus Ins Netz.” E-Forschungsberichte des DAI 2019/2. E-Forschungsberichte Des DAI. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2236/6674

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lucas, Gavin. 2022. “Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7622162

Pickering, Andrew, and Keith Guzik, eds. 2009. The Mangle in Practice: Science, Society, and Becoming. The Mangle in Practice. Science and Cultural Theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rösler, Katja. 2016. “Mit Den Dingen Rechnen: ‚Kulturen‘-Forschung Und Ihr Geselle Computer.” In Massendinghaltung in Der Archäologie. Der Material Turn Und Die Ur- Und Frühgeschichte, edited by Kerstin P. Hofmann, Thomas Meier, Doreen Mölders, and Stefan Schreiber, 93–110. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

DOI or URL of the preprint: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7304578

Version of the preprint: 1

Dear editors,

thank you for the reviews, which we have considered carefully. In the attached file you will find our comments (marked in blue) on the objections made, as well as references to changes we made in the paper itself. The reviews certainly have helped to identify somewhat blurry parts of the text. We hope its revised version will be accepted to the volume.

Warm regards,

Frederic, Katja, Wenke, Kerstin

and Shumon Tobias Hussain

and Shumon Tobias Hussain , posted 14 Dec 2022, validated 14 Dec 2022

, posted 14 Dec 2022, validated 14 Dec 2022Dear authors,

many thanks for going along with our PCI-based review and revision process. As you will see from the reviewers' comments, your chapter is considered a valuable contribution, packed with useful observations and insights. One of the reviewers is overall very positive indeed,although he also calls for a more critical and broader contextualisation of the results.

The other reviewer somewhat more critical, also highlighting some more technical issues as well as the at times unnecessarily opaque language. What also stands out is that perhaps the whole text could be re-framed not as a workshop report but a contribution that only refers to the workshop in passing but focusses more on the actual results and insights? If the workshop framing is retained, please consider outlining the rationale, aim, etc. of that meeting in more detail (although I would strongly recommend you to tone down the workshop component).

Overall, this is a really interesting and strong chapter that will fit beautifully into the volume - thank you for your submission; I look forward to seeing your revised version in due time.

, 28 Nov 2022

, 28 Nov 2022The manuscript is well written, clear, and comprehensive. The paper describes a project still in development and discussion. To my knowledge, there are no flaws in the analysis or the design of the research. There are also no ethic concerns with this paper. The only thing missing is a more detailed discussion at the end.

The title clearly reflects the content of the article. Although the abstract offers a good overview of the article, it does not provide the findings itself. The motivation for the study is clearly indicated in the introduction and based on the need to link so-called thing-editions, meaning lists of archaeological objects recorded in a normed data format, to open data repositories or databases. Based on two practical examples, the authors want to present the concept of digital transformation in this study. The research question here lies in understanding how two different concepts of order are functioning as part of circulating references. The study is done with the distinct goal of integrating these thing-editions in an already existing framework of the German Archaeological Institute (iDAI.world).

As methods, the authors rely on Brunu Latours terms of “inscription”, which describes fixed results in research processes and “circulating references”, which describes the process of knowledge making due to the research process and how these developments (called “trade-offs”) are forming what is considered the state of the art. The chapter on Latours theories is well written and understandable but could use one concrete example for illustration.

After that, the materials are described, which consist of the Corpus of Roman Finds in European Barbaricum (CRFB) on the one side and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae (Conspectus) on the other. The first data set (CRBF) is focusing on the dating of the objects, which oftentimes are not exactly described. As certain types are indicating certain chronological dates, others are vaguer and can only refer the dating frames. By utilizing a typochonological module, the authors present how dating in even vaguely described objects can be done. This part is very well written and understandable. The second example (Conspectus) is focusing on the form of the object and the integration of a well-established form catalogue into the iDAI.Objects database. The collection of Terra Sigillata types provided by Ettlinger can therefore be integrated into the databases of iDAI.Objects as well as iDAI.world. This part, although shorter, is written well, but I would have wished for some more paragraphs on the integration of Ettlingers system into iDAI.Objects and ultimately into iDAI.world.

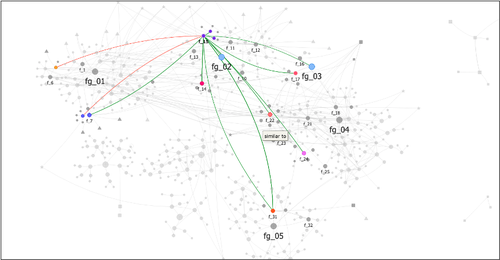

A very innovative idea is the Archaeological Form Slider with which the authors want to create a gaming component to the database, with which researchers could build their own Terra Sigillata profiles to see if they discovered a new form or an existing one. Another approach described is the Relation Diagram, which as well is a nice implementation for the data in the database. Both ideas are still in development, but well described.

Instead of Results and Discussion, the authors offer a Synthesis in which they summarize the application of Latours terms and the compensations for his trade-offs in archaeological data. This chapter falls too short as it does not include any further discussion of the results or problematizes other categories (except dating or form) not covered in this article. One could for example discuss the value of that classification system for the future in more detail. How should it be developed further? In which ways could Machine Learning contribute?

The references are well made and comprehensive. To my understanding, the amount of citations within the paper is appropriate.The figures were well chosen and well described. The tables were understandable as well.

From paper to byte: A workshop report on the digital transformation of two things editions

The paper focuses on the considerations involved in the creation of archaeological reference manuals in general and their digitalisation in particular. The challenges of the digitizing process are illustrated on two major reference collections, the Corpus of Roman finds in the Barbaricum (CFRB) and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae (Conspectus). The translation of a resource from analogue to digital format forces the authors to re-evaluate how 'types' and 'classifications' are created in catalogs and what effect they have on the standardization of archaeological practice and discourse. To address these issues, authors effectively utilize the theoretical framework of Latour (2002), using his 'inscription' and 'circulating reference' to refer to each thing or ideal type that becomes a scientific entity through its catalog description. Such type both expands and limits the possibilities of researchers, in amplifying compatibility, standardization and calculation on one hand and reducing the objects particularity, variety and locality on the other. Authors zoom in on the digitalisation of the varied chrono-types and artifact forms, the two main ordering concepts in the CFRB and Conspectus resources. Both these concepts are implemented through group-based taxonomies, where the variants and core type maintain functional but malleable dependency. As each variant needs to be digitized, and broken out of its defining frame, the delineation of these taxonomies is called for re-evaluation, the omissions are rendered explicit and visible, and solutions are devised for information that is the property of the group rather than individual artefacts.

While this paper discusses classifications pertinent to researchers studying the material culture of Roman Limes, the issues raised with regard to creation of digital standards are relevant for all historical digital archives as they are generalized/globally applicable.

The sections on the chrono-types and artefact form taxonomies were clear for someone who deals with this material culture and digital archives, but will be hard to read by a novice to these topics. I particularly enjoyed the final section on the FormSlider and relation diagram, interactive tools that can verify and validate type definitions. Such tools fulfill the promise of the digital medium.

The manuscript is fairly densely written and could use more active voice, less vagueness and more consistency in spelling key words, such as Roman Era (the term Roman appears throughout the article with both upper and lower case, which is simply disturbing). The rationale is clear in the introduction, however it is hard to follow up in the rest of the paper, which focuses on the description of the structure of the analogue resources and their digital handling:

- Authors entitled the manuscript to be a report on the results of a workshop, but workshop agenda, aims and participants remain unspecified, and thus the stakeholders and adopters/users of the new digital resources remain muted and devoid of agency.

- When opening the paper, the authors declare that they are "not concerned with the making or publishing process but with the possibilities and limitations of working with aggregate information in the context of catalogues " (3-4). Yet there are no examples of aggregate analysis of the catalog data in the paper, not even as putative scenarios or use cases. A lot of attention paid to the translation of the various typochronological modules and artefact forms into a digital format, which seems perfectly legitimate and the authors might want to say include in the introduction.

The article utilizes a lot of 10-dollar and abstract terms where simpler ones might be substituted. Some of the figures (4, 5, 6 are small and bordering on non-legible A native speaker editor with a focus on consistency and readability is recommended. Occasionally the text suffers from vagueness and sometimes leaves the reader hanging entirely :

"Thus, in CRFB, the specific bead, casserole, and fibula found in graves [...] are not merely grave gifts for a deceased anymore. " (p.12) I have read this sentence several times and still wonder what the authors intended. Shared implicit knowledge is expected from the reader, who would rather hear what the bead, casserole and fibula have become from the authors, rather than wonder herself.

The overall aim of exploring how digitalisation impacts the work with aggregate information in the catalogues could be addressed more thoroughly:

- The authors seem silent or equivocal on the impact of digitalization. While they consider digitisation important, they do not differentiate between 1.0 and 2.0 approaches, and fail to address the impact of different digital solutions to the specific problems of typochronological module or artifact form taxonomies.

- Authors support LOUD data creation, mostly so that the data can be connected to other DAI digital collections, but again the concern for the usability of the result is missing. How many of the user community can effectively query LOUD data and how usability guaranteed?

- The authors problematize the missing and vague dating intervals in the CRFB, yet rarely specify the limitations this actually imposes on aggregate research. Do researchers avoid such records? Does the search algorithm leave them out? Do machines and people actively discard broadly dated records? We learn little about the particular failure mode the authors fear with the digital medium. The authors also seem unaware of the numerous tools that have been designed to deal with chronologically broad or uncertain data (e.g chronolog, tempun in Python just to mention a few).

-Likewise the group structure of forms in the Conspectus is described, but no actual comparison of the digital vs analogue resource usage of the shape taxonomy is presented, thus leaving the reader wondering about the actual impact of digitisation and missing the mark of being able to gauge the limitations and possibilities with reference to analogue resource.

The way analogue resources are transformed into digital format matters. Each tool has its affordances which is a reason why many digitization projects take stock from user groups as to what their research goals are so as to minimize the constraints imposed by the new medium, and to take advantage of the new affordances inherited from it. Authors fail to discuss such a process, which leaves the article and digitisation process without a frame of reference that could serve as a clear measure against which the final outcome can be evaluated. Authors also miss a chance here to explore which catalogues hold more authority with the users: analogue or digital ones?

One particularly striking omission was the lack of connection to other digitisation /standardisation initiatives in other EU or US where initiatives (DINAA, tDAR, Getty Museum) too are engaged in the digitisation of cultural heritage collections and their systematisation through reference manuals.