Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Feb 2024

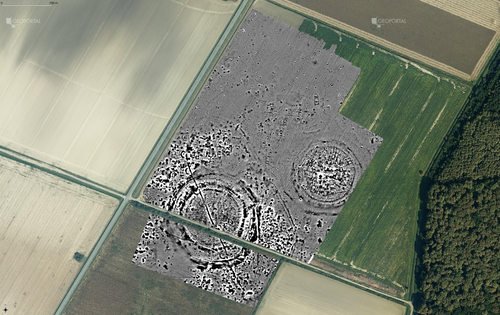

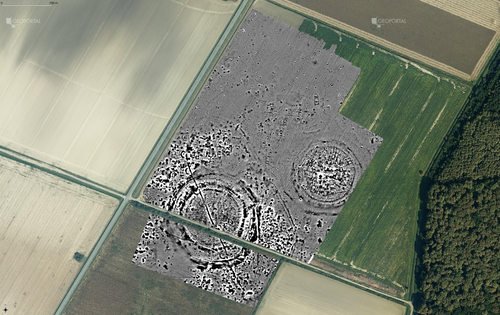

Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern CroatiaSosic Klindzic Rajna; Vuković Miroslav; Kalafatić Hrvoje; Šiljeg Bartul https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970703What lies on top lies also beneath? Connecting crop surface modelling to buried archaeology mapping.Recommended by Markos Katsianis based on reviews by Ian Moffat and Geert Verhoeven based on reviews by Ian Moffat and Geert Verhoeven

This paper (Sosic et al. 2024) explores the Neolithic landscape of the Sopot culture in Đakovština, Eastern Slavonija, revealing a network of settlements through a multi-faceted approach that combines aerial archaeology, magnetometry, excavation, and field survey. This strategy facilitates scalable research tailored to the particularities of each site and allows for improved representations of buried archaeology with minimal intrusion. Using the site of Tomašanci-Dubrava as an example of the overall approach, the study further explores the use of drone imagery for 3D surface modeling, revealing a consistent correlation between crop surface elevation during full plant growth and ground terrain after ploughing, attributed to subsurface archaeological features. Results are correlated with magnetic survey and test-pitting data to validate the micro-topography and clarify the relationship between different subsurface structures. The results obtained are presented in a comprehensive way, including their source data, and are contextualized in relation to conventional cropmark detection approaches and expectations. I found this aspect very interesting, since the crop surface and terrain models contradict typical or textbook examples of cropmark detection, where the vegetation is projected to appear higher in ditches and lower in areas with buried archaeology (Renfrew & Bahn 2016, 82). Regardless, the findings suggest the potential for broader applications of crop surface or canopy height modelling in landscape wide surveys, utilizing ALS data or aerial photographs. It seems then that the authors make a valid argument for a layered approach in landscape-based site detection, where aerial imagery can be used to accurately map the topography of areas of interest, which can then be further examined at site scale using more demanding methods, such as geophysical survey and excavation. This scalability enhances the research's relevance in broader archaeological and geographical contexts and renders it a useful example in site detection and landscape-scale mapping. References Renfrew, C. and Bahn, P. (2016). Archaeology: theories, methods and practice. Thames and Hudson. Sosic Klindzic, R., Vuković, M., Kalafatić, H. and Šiljeg, B. (2024). Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern Croatia, Zenodo, 7970703, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970703 | Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern Croatia | Sosic Klindzic Rajna; Vuković Miroslav; Kalafatić Hrvoje; Šiljeg Bartul | <p>This paper presents the results of a study on the neolithic landscape of the Sopot culture in the area of Đakovština in Eastern Slavonija. A vast network of settlements was uncovered using aerial archaeology, which was further confirmed and chr... |  | Landscape archaeology, Neolithic, Remote sensing, Spatial analysis | Markos Katsianis | 2023-09-01 12:57:04 | View | |

17 Dec 2020

Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbolsGuillaume Porraz, John E. Parkington, Patrick Schmidt, Gérald Bereiziat, Jean-Philip Brugal, Laure Dayet, Marina Igreja, Christopher E. Miller, Viola C. Schmid, Chantal Tribolo, Aurore Val, Christine Verna, Pierre-Jean Texier https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/ch53rExperimentation as a driving force for innovation in the Pre-Still Bay from Southern AfricaRecommended by Anne Delagnes based on reviews by Francesco d'Errico, Enza Elena Spinapolice and Kathryn RanhornThe article submitted by Guillaume Porraz et al. [1] shed light on the evolutionary changes recorded during the Pre-Still Bay Lynn stratigraphic unit (SU) from Diepkloof (Southern Africa). It promotes a multi-proxy and integrative approach based on a set of innovative behaviors, such as the engraving of geometric forms, silcrete heat- treatment, the use of adhesive, bladelet and bifacial tools production. This approach is not so common in Middle Stone Age (MSA) studies and makes a lot of sense for discussing the mechanisms that have fostered later innovations during the Still Bay and Howiesons Poort periods. The various innovations that emerge synchronously in this layer contrast with earlier innovations which appear as isolated phenomena in the MSA archaeological record. The strong inventiveness documented in Lynn SU is reported to a phase of experimentation for testing new ideas, new behaviors that would have played a crucial role for the emergence of the Still Bay in a context of socio-economic transformation. The data presented in this article broadens the scope of two previous articles [2-3] based on a more representative record, collected on an area of 3,5 m² opposed to 2 m² previously, and on the first presentation and description of an engraved bone with a rhomboid pattern. Macro- and microscopic analyses together with the analysis of the distribution of the engraved lines argue convincingly for an intentional engraving. This article constitutes a key contribution to the question of HOW emerged modern cultures in Southern Africa, while calling for further research related to sites’ function, environment and local resources to address the ever-debated question of WHY the MSA groups from Southern Africa developed such unprecedented inventiveness. It makes no doubt that this article deserves recommendation by PCI Archaeology. [1] Porraz, G., Schmidt, P., Bereiziat, G., Brugal, J.Ph., Dayet, L., Igreja, M., Miller, C.E., Viola, C., Tribolo, C., Val, A., Verna, C., Texier, P.J. 2020. Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbols. 10.32942/osf.io/ch53r [2] Porraz, G., Texier, P.J., Archer, W., Piboule, M., Rigaud, J.P, Tribolo, C. 2013. Technological successions in the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science 40, 3376–3400. 10.1016/j.jas.2013.02.012 [3] Porraz, G., Texier, J.P. Miller, C.E., 2014. Le complexe bifacial Still Bay et ses modalités d’émergence à l’abri Diepkloof (Middle Stone Age, Afrique du Sud). In: XXVIIème Congrès Préhistorique de France, Transitions, Ruptures et Continuité en Préhistoire. Mémoires de la Société Préhistorique Française, 155–175. | Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbols | Guillaume Porraz, John E. Parkington, Patrick Schmidt, Gérald Bereiziat, Jean-Philip Brugal, Laure Dayet, Marina Igreja, Christopher E. Miller, Viola C. Schmid, Chantal Tribolo, Aurore Val, Christine Verna, Pierre-Jean Texier | <p>In South Africa, key technologies and symbolic behaviors develop as early as the later Middle Stone Age in MIS5. These innovations arise independently in various places, contexts and forms, until their full expression during the Still Bay and t... |  | Africa, Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic, Symbolic behaviours | Anne Delagnes | 2020-08-04 09:13:27 | View | |

20 Jul 2022

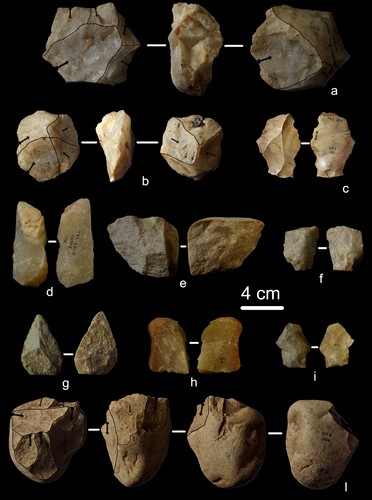

Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, IsraelNimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4New zooarchaeological data from the Upper Palaeolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2, IsraelRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio

The Levantine Corridor is considered a crossing point to Eurasia and one of the main areas for detecting population flows (and their associated cultural and economic changes) during the Pleistocene. This area could have been closed during the most arid periods, giving rise to processes of population isolation between Africa and Eurasia and intermittent contact between Eurasian human communities [1,2]. Zooarchaeological studies of the early Upper Palaeolithic assemblages constitute an important source of knowledge about human subsistence, making them central to the debate on modern behaviour. The Early Upper Palaeolithic sequence in the Levant includes two cultural entities – the Early Ahmarian and the Levantine Aurignacian. This latter is dated to 39-33 ka and is considered a local adaptation of the European Aurignacian techno-complex. In this work, the authors present a zooarchaeological study of the Nahal Rahaf 2 (ca. 35 ka) archaeological site in the southern Judean Desert in Israel [3]. Zooarchaeological data from the early Upper Paleolithic desert regions of the southern Levant are not common due to preservation problems of non-lithic finds. In the case of Nahal Rahaf 2, recent excavation seasons brought to light a stratigraphical sequence composed of very well-preserved archaeological surfaces attributed to the 'Arkov-Divshon' cultural entity, which is associated with the Levantine Aurignacian. This study shows age-specific caprine (Capra cf. Capra ibex) hunting on prime adults and a generalized procurement of gazelles (Gazella cf. Gazella gazella), which seem to have been selectively transported to the site and processed for within-bone nutrients. An interesting point to note is that the proportion of goats increases along the stratigraphic sequence, which suggests to the authors a specialization in the economy over time that is inversely related to the occupational intensity of use of the site. It is also noteworthy that the materials represent a large sample compared to previous studies from the Upper Paleolithic of the Judean Desert and Negev. In summary, this manuscript contributes significantly to the study of both the palaeoenvironment and human subsistence strategies in the Upper Palaeolithic and provides another important reference point for evaluating human hunting adaptations in the arid regions of the southern Levant. References [1] Bermúdez de Castro, J.-L., Martinon-Torres, M. (2013). A new model for the evolution of the human pleistocene populations of Europe. Quaternary Int. 295, 102-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.036 [2] Bar-Yosef, O., Belfer-Cohen, A. (2010). The Levantine Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic. In Garcea, E.A.A. (Ed), South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples Between 130,000 and 10,000 Years Ago. Oxbow Books, pp. 144-167. [3] Marom, N., Gnezdilov, D. L., Shafir, R., Barzilai, O. and Shemer, M. (2022). Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel. BioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492258, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4 | Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel | Nimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer | <p>Nahal Rahaf 2 (NR2) is an Early Upper Paleolithic (ca. 35 kya) rock shelter in the southern Judean Desert in Israel. Two excavation seasons in 2019 and 2020 revealed a stratigraphical sequence composed of intact archaeological surfaces attribut... |  | Upper Palaeolithic, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Joana Gabucio | 2022-05-19 06:16:47 | View |

12 Feb 2024

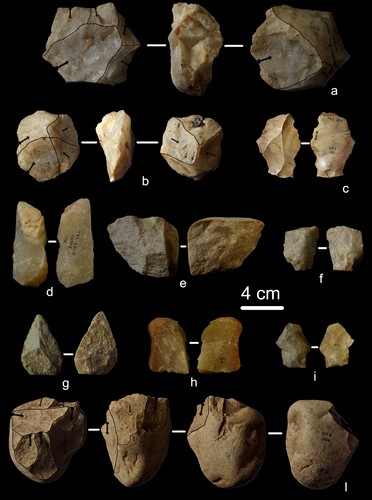

First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy)Sara Daffara, Carlo Giraudi, Gabriele L.F. Berruti, Sandro Caracausi, Francesca Garanzini https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4ufNot Simply the Surface: Manifesting Meaning in What Lies Above.Recommended by Marcel Kornfeld based on reviews by Lawrence Todd, Jason LaBelle and 2 anonymous reviewersThe archaeological record comes in many forms. Some, such as buried sites from volcanic eruptions or other abrupt sedimentary phenomena are perhaps the only ones that leave relatively clean snapshots of moments in the past. And even in those cases time is compressed. Much, if not all other archaeological record is a messy affair. Things, whatever those things may be, artifacts or construction works (i.e., features), moved, modified, destroyed, warped and in a myriad of ways modified from their behavioral contexts. Do we at some point say the record is worthless? Not worth the effort or continuing investigation. Perhaps sometimes this may be justified, but as Daffara and colleagues show, heavily impacted archaeological remains can give us clues and important information about the past. Thoughtful and careful prehistorians can make significant contributions from what appear to be poor archaeological records. In the case of Daffara and colleagues, a number of important theoretical cross-sections can be recognized. For a long time surface archaeology was thought of simply as a way of getting a preliminary peak at the subsurface. From some of the earliest professional archaeologists (e.g., Kidder 1924, 1931; Nelson 1916) to the New Archaeologists of the 1960s, the link between the surface and subsurface was only improved in precision and systematization (Binford et al. 1970). However, at Hatchery West Binford and colleagues not only showed that surface material can be used more reliably to get at the subsurface, but that substantive behavioral inferences can be made with the archaeological record visible on the surface. Much more important are the behavioral implications drawn from surface material. I am not sure we can cite the first attempts at interpreting prehistory from the surface manifestations of the archaeological record, but a flurry of such approaches proliferated in the 1970s and beyond (Dunnell and Dancey 1983; Ebert 1992; Foley 1981). Off-site archaeology, non-site archaeology, later morphing into landscape archaeology all deal strictly with surface archaeological record to aid in understanding the past. With the current paper, Daffara and colleagues (2024) are clearly in this camp. Although still not widely accepted, it is clear that some behaviors (parts of systems) can only be approached from surface archaeological record. It is very unlikely that a future archaeologist will be able to excavate an entire human social/cultural system; people moving from season to season, creating multiple long and short term camps, travelling, procuring resources, etc. To excavate an entire system one would need to excavate 20,000 km2 or some similarly impossible task. Even if it was physically possible to excavate such an enormous area, it is very likely that some of contextual elements of any such system will be surface manifestations. Without belaboring the point, surface archaeological record yields data like any other archaeological record. We must contextual the archaeological artifacts or features weather they come from surface or below. Daffara and colleagues show us that we can learn about deep prehistory of northern Italy, with collections that were unsystematically collected, biased by agricultural as well as other land deformations agents. They carefully describe the regional prehistory as we know it, in particular specific well documented sites and assemblages as a means of applying such knowledge to less well controlled or uncontrolled collections.

References Binford, L., Binford, R. S. R., Whallon, R. and Hardin, M. A. (1970). Archaeology of Hatchery West. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, No. 24, Washington D.C. Daffara, S., Giraudi, C., Berruti, G. L. F., Caracausi, S. and Garanzini, F. (2024). First evidence of a Palaeolithic frequentation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy), OSF Preprints, pz4uf, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4uf Dunnell, R. C. and Dancey, W. S. (1983). The siteless survey: a regional scale data collection strategy. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 6, edited by Michael B. Schiffer, pp. 267-287. Academic Press, New York. Ebert, J. I. (1992). Distributional Archaeology. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. Foley, R. A. (1981). Off site archaeology and human adaptation in eastern Africa: An analysis of regional artefact density in the Amboseli, Southern Kenya. British Archaeological Reports International Series 97. Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 3. Oxford England. Kidder, A. V. (1924). An Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology, With a Preliminary Account of the Excavations at Pecos. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy, no. 1. New Haven, Connecticut. Kidder, A. V. (1931). The Pottery of Pecos, vol. 1. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy. New Haven, Connecticut. Nelson, N. (1916). Chronology of the Tano Ruins, New Mexico. American Anthropologist 18(2):159-180. | First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy) | Sara Daffara, Carlo Giraudi, Gabriele L.F. Berruti, Sandro Caracausi, Francesca Garanzini | <p>The Trino hill is an isolated relief located in north-western Italy, close to Trino municipality. The hill was subject of multidisciplinary studies during the 1970s, when, because of quarrying and agricultural activities, five concentrations of... |  | Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic | Marcel Kornfeld | 2023-10-04 16:58:19 | View | |

20 Dec 2020

For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente.Marco Carpentieri, Marta Arzarello https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/2ptjbInvestigating the opportunistic debitage – an experimental approachRecommended by Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by David Hérisson and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper “For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente” [1] submitted by M. Carpentieri and M. Arzarello is a welcome addition to a growing number of studies focusing on flaking methods showing little to no core preparation, e.g., [2–4]. These flaking methods are often overlooked or seen as ‘simple’, which, in a Middle Palaeolithic context, sometimes leads to a dichotomy of Levallois vs. non-Levallois debitage (e.g., see discussion in [2]). The authors address this topic by first providing a definition for ‘opportunistic debitage’, derived from the definition of the ‘Alternating Surfaces Debitage System’ (SSDA, [5]). At the core of the definition is the adaptation to the characteristics (e.g., natural convexities and quality) of the raw material. This is one main challenge in studying this type of debitage in a consistent way, as the opportunistic debitage leads to a wide range of core and flake morphologies, which have sometimes been interpreted as resulting from different technical behaviours, but which the authors argue are part of a same ‘methodological substratum’ [1]. This article aims to further characterise the ‘opportunistic debitage’. The study relies on four archaeological assemblages from Italy, ranging from the Lower to the Upper Pleistocene, in which the opportunistic debitage has been recognised. Based on the characteristics associated with the occurrence of the opportunistic debitage in these assemblages, an experimental replication of the opportunistic debitage using the same raw materials found at these sites was conducted, with the aim to gain new insights into the method. Results show that experimental flakes and cores are comparable to the ones identified as resulting from the opportunistic debitage in the archaeological assemblage, and further highlight the high versatility of the opportunistic method. One outcome of the experimental replication is that a higher flake productivity is noted in the opportunistic centripetal debitage, along with the occurrence of 'predetermined-like' products (such as déjeté points). This brings the authors to formulate the hypothesis that the opportunistic debitage may have had a role in the process that will eventually lead to the development of Levallois and Discoid technologies. How this articulates with for example current discussions on the origins of Levallois technologies (e.g., [6–8]) is an interesting research avenue. This study also touches upon the question of how the implementation of one knapping method may be influenced by the broader technological knowledge of the knapper(s) (e.g., in a context where Levallois methods were common vs a context where they were not). It makes the case for a renewed attention in lithic studies for flaking methods usually considered as less behaviourally significant. [1] Carpentieri M, Arzarello M. 2020. For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente. OSF Preprints, doi:10.31219/osf.io/2ptjb [2] Bourguignon L, Delagnes A, Meignen L. 2005. Systèmes de production lithique, gestion des outillages et territoires au Paléolithique moyen : où se trouve la complexité ? Editions APDCA, Antibes, pp. 75–86. Available: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00447352 [3] Arzarello M, De Weyer L, Peretto C. 2016. The first European peopling and the Italian case: Peculiarities and “opportunism.” Quaternary International, 393: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.005 [4] Vaquero M, Romagnoli F. 2018. Searching for Lazy People: the Significance of Expedient Behavior in the Interpretation of Paleolithic Assemblages. J Archaeol Method Theory, 25: 334–367. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9339-x [5] Forestier H. 1993. Le Clactonien : mise en application d’une nouvelle méthode de débitage s’inscrivant dans la variabilité des systèmes de production lithique du Paléolithique ancien. Paléo, 5: 53–82. doi:10.3406/pal.1993.1104 [6] Moncel M-H, Ashton N, Arzarello M, Fontana F, Lamotte A, Scott B, et al. 2020. Early Levallois core technology between Marine Isotope Stage 12 and 9 in Western Europe. Journal of Human Evolution, 139: 102735. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102735 [7] White M, Ashton N, Scott B. 2010. The emergence, diversity and significance of the Mode 3 (prepared core) technologies. Elsevier. In: Ashton N, Lewis SG, Stringer CB, editors. The ancient human occupation of Britain. Elsevier. Amsterdam, pp. 53–66. [8] White M, Ashton N. 2003. Lower Palaeolithic Core Technology and the Origins of the Levallois Method in North‐Western Europe. Current Anthropology, 44: 598–609. doi:10.1086/377653 | For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente. | Marco Carpentieri, Marta Arzarello | <p>The opportunistic debitage, originally adapted from Forestier’s S.S.D.A. definition, is characterized by a strong adaptability to local raw material morphology and its physical characteristics and it is oriented towards flake production. Its mo... |  | Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic | Alice Leplongeon | 2020-07-23 14:26:04 | View | |

06 Oct 2023

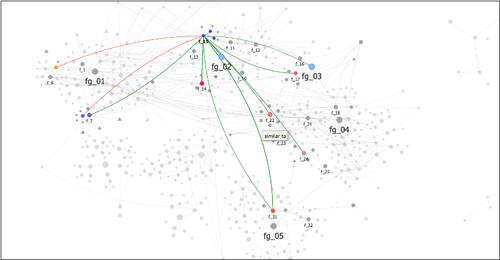

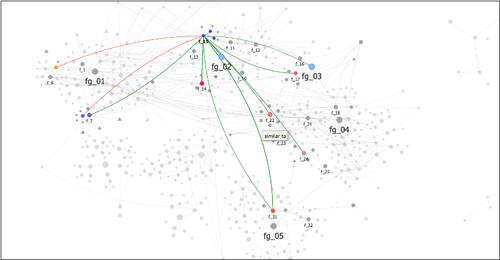

From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editionsAuth. Frederic; Rösler, Katja; Domscheit, Wenke; Hofmann, Kerstin P. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7304578Revitalising archaeological corpus publications through digitisation – the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae as exemplary casesRecommended by Felix Riede, Sébastien Plutniak and Shumon Tobias Hussain and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova

The paper entitled “From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions” submitted by Frederic Auth and colleagues discusses how those rich and often meticulously illustrated catalogues of particular find classes that exist in many corners of archaeology can be brought to the cutting edge of contemporary research through digitisation. This paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology, taxonomy, classification theory, and computational approaches in archaeology. Auth et al. (2023) begin with outlining the useful notion of the ‘thing-edition’ originally coined by Kerstin Hofmann in the context of her work with the many massive corpora of finds that have characterised, in particular, earlier archaeological knowledge production in Germany (Hofmann et al. 2019; Hofmann 2018). This work critically examines changing trends in the typological characterisation and recording of various find categories, their theoretical foundations or lack thereof and their legacy on contemporary practice. The present contribution focuses on what happens with such corpora when they are integrated into digitisation projects, specifically the efforts by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), the so-called iDAI.world and in regard to two Roman-era material culture groups, the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum (Roman finds from beyond the empire’s borders in eight printed volumes covering thousands of finds of various categories), and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae (Roman plain ware). Drawing on Bruno Latour’s (2005) actor-network theory (ANT), Auth et al. discuss and reflect on the challenges met and choices to be made when thing-editions are to be transformed into readily accessible data, that is as linked to open, usable data. The intellectual and infrastructural workload involved in such digitisation projects is not to be underestimated. Here, the contribution by Auth et al. excels in the manner that it does not present the finished product – the fully digitised corpora – but instead offers a glimpse ‘under the hood’ of the digitisation process as an interaction between analogue corpus, research team, and the technologies at hand. These aspects were rarely addressed in the literature, rooted in the 1970s early work (Borillo and Gardin 1974; Gaines 1981), on archaeological computerised databases, focused on technical dimensions (see Rösler 2016 for an exception). Their paper can so also be read in the broader context of heterogeneous computer-assisted knowledge ecologies and ‘mangles of practice’ (see Pickering and Guzik 2009) in which practitioners and technological structures respond to each other’s needs and attempt to cooperate in creative ways. As such, Auth et al.’s considerations not least offer valuable resources for Science and Technology Studies-inspired discussions on the cross-fertilization of archaeological theory, practice and currently emerging material and virtual research infrastructures and can be read in conjunction to Gavin Lucas’ (2022) paper on ‘machine epistemology’ due to appear in the same volume. Perhaps more importantly, however, the work by Auth and colleagues (2023) exemplifies the due diligence required in not merely turning a catalogue from paper to digital document but in transforming such catalogues into long-lasting and patently usable repositories of generations of scholars to come. Deploying the Latourian notions of trade-off and recursive reference, Auth et al. first examine the structure, strengths, and weakness of the two corpora before moving on to showing how the freshly digitised versions offer new and alternative ways of analysing the archaeological material at hand, notably through immediate visualisation opportunities, through ceramic form combinations, and relational network diagrams based on the data inherent in the respective thing-editions. Catalogues including basic descriptions and artefact illustrations exist for most if not all archaeological periods. They constitute an essential backbone of archaeological work as repeated access to primary material is impractical if not impossible. The catalogues addressed by Auth et al. themselves reflect major efforts on behalf of archaeological experts to arrive at clear and operational classifications in a pre-computerised era. The continued and expanded efforts by Auth and colleagues build on these works and clearly demonstrate the enormous analytical potential to make such data not merely more accessible but also more flexibly interoperable. Their paper will therefore be an important reference for future work with similar ambitions facing similar challenges. References Auth, Frederic, Katja Rösler, Wenke Domscheit, and Kerstin P. Hofmann. 2023. “From Paper to Byte: A Workshop Report on the Digital Transformation of Two Thing Editions.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8214563 Borillo, Mario, and Jean-Claude Gardin. 1974. Les Banques de Données Archéologiques. Marseille: Éditions du CNRS. Gaines, Sylvia W., ed. 1981. Data Bank Applications in Archaeology. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. Hofmann, Kerstin P. 2018. “Dingidentitäten Und Objekttransformationen. Einige Überlegungen Zur Edition von Archäologischen Funden.” In Objektepistemologien. Zum Verhältnis von Dingen Und Wissen, edited by Markus Hilgert, Kerstin P. Hofmann, and Henrike Simon, 179–215. Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 59. Berlin: Edition Topoi. https://dx.doi.org/10.17171/3-59 Hofmann, Kerstin P., Susanne Grunwald, Franziska Lang, Ulrike Peter, Katja Rösler, Louise Rokohl, Stefan Schreiber, Karsten Tolle, and David Wigg-Wolf. 2019. “Ding-Editionen. Vom Archäologischen (Be-)Fund Übers Corpus Ins Netz.” E-Forschungsberichte des DAI 2019/2. E-Forschungsberichte Des DAI. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2236/6674 Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lucas, Gavin. 2022. “Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7622162 Pickering, Andrew, and Keith Guzik, eds. 2009. The Mangle in Practice: Science, Society, and Becoming. The Mangle in Practice. Science and Cultural Theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Rösler, Katja. 2016. “Mit Den Dingen Rechnen: ‚Kulturen‘-Forschung Und Ihr Geselle Computer.” In Massendinghaltung in Der Archäologie. Der Material Turn Und Die Ur- Und Frühgeschichte, edited by Kerstin P. Hofmann, Thomas Meier, Doreen Mölders, and Stefan Schreiber, 93–110. Leiden: Sidestone Press. | From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions | Auth. Frederic; Rösler, Katja; Domscheit, Wenke; Hofmann, Kerstin P. | <p>One specific form of publication for archaeological objects are catalogues, atlases and corpora. Kerstin Hofmann has introduced the term ‘Ding-Editionen’ (thing editions) for this category of publications that present their data in lists, short... |  | Antiquity, Computational archaeology, Dating, Theoretical archaeology | Felix Riede | 2022-11-08 16:00:49 | View | |

28 Aug 2023

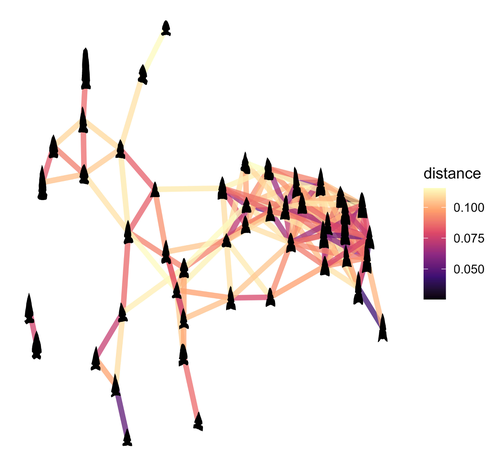

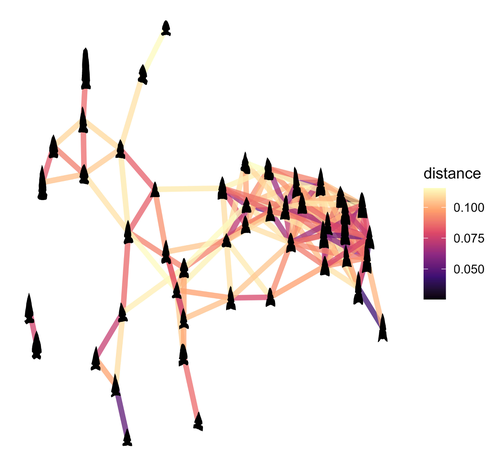

Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Projectile Points from the Southwest United StatesRobert J. Bischoff https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/a6wjc2D Geometric Morphometrics of Projectile Points from the Southwestern United StatesRecommended by Adrian L. Burke based on reviews by James Conolly and 1 anonymous reviewerBischoff (2023) is a significant contribution to the growing field of geometric morphometric analysis in stone tool analysis. The subject is projectile points from the southwestern United States. Projectile point typologies or systematics remain an important part of North American archaeology, and in fact these typologies continue to be used primarily as cultural-historical markers. This article looks at projectile point types using a 2D image geometric morphometric analysis as a way of both improving on projectile point types but also testing if these types are in fact based in measurable reality. A total of 164 point outlines are analyzed using Elliptical Fourier, semilandmark and landmark analyses. The author also uses a network analysis to look at possible relationships between projectile point morphologies in space. This is a clever way of working around the predefined distributions of projectile point types, some of which are over 100 years old. Because of the dynamic nature of stone tools in terms of their use, reworking and reuse, this article can also provide solutions for studying the dynamic nature of stone tools. This article therefore also has a wide applicability to other stone tool analyses. Reference Bischoff, R. J. (2023) Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Projectile Points from the Southwest United States, SocArXiv, a6wjc, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/a6wjc | Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Projectile Points from the Southwest United States | Robert J. Bischoff | <p style="text-align: justify;">Traditional analyses of projectile points often use visual identification, the presence or absence of discrete characteristics, or linear measurements and angles to classify points into distinct types. Geometric mor... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology, Lithic technology, North America | Adrian L. Burke | 2022-12-18 03:38:14 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific RegionChristopher Buckley https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2From Polished Stone Tools to Population Dynamics: Ethnographic Archives as InsightsRecommended by Solène Denis based on reviews by Adrian L. Burke and 1 anonymous reviewerMost archaeological contexts provide objects without organic materials making them quite silent regarding their hafting techniques and use. This is especially true for the polished stone tools that only thanks to a few discoveries in a wet environment, we can obtain some insights regarding their hafting techniques. Use-wear analysis can also be of some support to get a better picture of these artefacts (e.g. Masclans Latorre 2020), whose typology testifies to an important diversity in European Neolithic contexts that sometimes are well-documented from the chaîne opératoire perspective (see De Labriffe and Thirault dir. 2012). The study offered by Chris Buckley (2023) constitutes an important contribution to animating these tools. His work relies on the Asia Pacific region, where he gathered data and mapped more than 300 ethnographic hafted stone and shell tools. This database is available on a webpage https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1D_sC7VUtQRuRcCgc9rROVU7ghrdiVAg&ll=-2.458804534247277%2C154.35254980859378&z=6, providing a short description and pictures of some of the items, completed by Supplementary data. Thanks to this important record of entire objects, the author presents the different possibilities regarding hafting styles, blade orientations and attachment techniques. The combination of these different characteristics led the author to the introduction of a dynamic typology based on the concept of ‘morphospace’. Eight types have been so identified for the Asia Pacific region. The geographical distribution of these types is then presented and questioned, bringing also to the forefront some archaeological findings. An emphasis is made on New Guinea island where documentation is important. We can mention the emblematic work of Anne-Marie and Pierre Pétrequin (1993 and 2020) focused on West Papua, providing one of the most consulted books on stone axes by archaeologists. The worthy explanations tested to understand this repartition mobilize archaeological or linguistic data to hypothesise a three waves model of innovations in link with agricultural practices. A discussion on the correlation between material culture and language highlights in the background the need for interdisciplinary to deal finely with these interactions and linkages as has been effectively demonstrated elsewhere (Hermann and Walworth 2020). To conclude, the convergence between European Neolithic and New Guinea polished stone tools is demonstrated here through ‘morphospace’ comparisons. Thanks to this study, the polished stone tools come alive more than any European archaeological context would allow. The population dynamics investigated through these tools are directly relevant to current scientific issues concerning material culture. This example of convergent evolution is therefore an important key to considering this article as a source of inspiration for the archaeological community. References Buckley C. (2023). Hafted Stone and Shell Tools in the Asia Pacific Region, PsyArXiv, v.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2 De Labriffe A., Thirault E. dir. (2012). Produire des haches au Néolithique, de la matière première à l’abandon, Paris, Société préhistorique française (Séances de la Société préhistorique française, 1). Hermann A., Walworth M. (2020). Approche interdisciplinaire des échanges interculturels et de l’intégration des communautés polynésiennes dans le centre du Vanuatu, Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 151, 239-262. https://doi-org.docelec.u-bordeaux.fr/10.4000/jso.11963 Masclans Latorre A. (2020). Use-wear Analyses of Polished and Bevelled Stone Artefacts during the Sepulcres de Fossa/Pit Burials Horizon (NE Iberia, c. 4000–3400 cal B.C.), Oxford, BAR Publishing (BAR International Series 2972). Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (1993). Écologie d'un outil : la hache de pierre en Irian Jaya (Indonésie), Paris, CNRS Editions. Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (2020). Ecology of a Tool: The ground stone axes of Irian Jaya (Indonesia). Oxbow Books. | Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific Region | Christopher Buckley | <p>Hafted stone tools fell into disuse in the Pacific region in the 19th and 20th centuries. Before this occurred, examples of tools were collected by early travelers, explorers and tourists. These objects, which now reside in ethnographic collect... |  | Asia, Conservation/Museum studies, Lithic technology, Neolithic, Oceania | Solène Denis | 2022-11-09 18:37:08 | View | |

20 Mar 2024

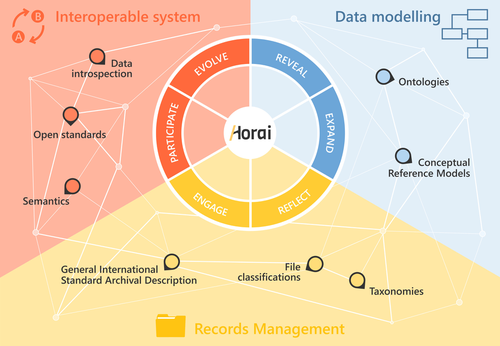

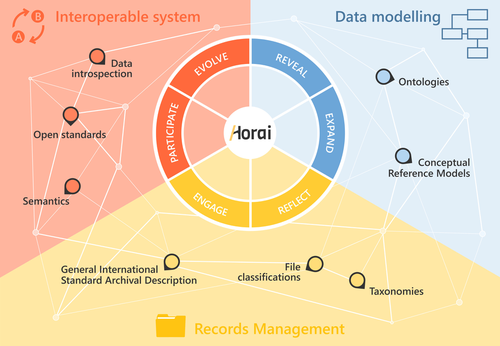

HORAI: An integrated management model for historical informationPablo del Fresno Bernal, Sonia Medina Gordo and Esther Travé Allepuz https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8185510A novel management model for historical informationRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Leandro Sánchez Zufiaurre and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper “HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information” presents a novel model for managing historical information. The study draws from an extensive indepth work in historical information management and a multi-disciplinary corpus of research ranging from heritage infrastructure research and practice to information studies and archival management literature. The paper ties into several key debates and discussions in the field showing awareness of the state-of-the-art of data management practice and theory. The authors argue for a new semantic data model HORAI and link it to a four-phase data management lifecycle model. The conceptual work is discussed in relation to three existing information systems partly predating and partly developed from the outset of the HORAI-model. While the paper shows appreciable understanding of the practical and theoretical state-of-the-art and the model has a lot of potential, in its current form it is still somewhat rough on the edges. Many of the both practical and theoretical threads introduced in the text warrant also more indepth consideration and it will be interesting to follow how the work will proceed in the future. For example, the comparison of the HORAI model and the ISAD(G): General International Standard Archival Description standard in the figure 1 is interesting but would require more elaboration. A slightly more thorough copyediting of the text would have also been helpful to make it more approachable. As a whole, in spite of the critique, I find both the paper and the model as valuable contributions to the literature and the practice of managing historical information. The paper reports thorough work, provides a lot of food for thought and several interesting lines of inquiry in the future. ReferencesDel Fresno Bernal, P., Medina Gordo, S. and Travé Allepuz, E. (2024). HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information. CAA 2023, Amsterdam, Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8185510 | HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information | Pablo del Fresno Bernal, Sonia Medina Gordo and Esther Travé Allepuz | <p>The archiving process goes beyond mere data storage, requiring a theoretical, methodological, and conceptual commitment to the sources of information. We present Horai as a semantic-based integration model designed to facilitate the development... |  | Computational archaeology, Spatial analysis | Isto Huvila | 2023-07-26 09:33:58 | View | |

14 Mar 2024

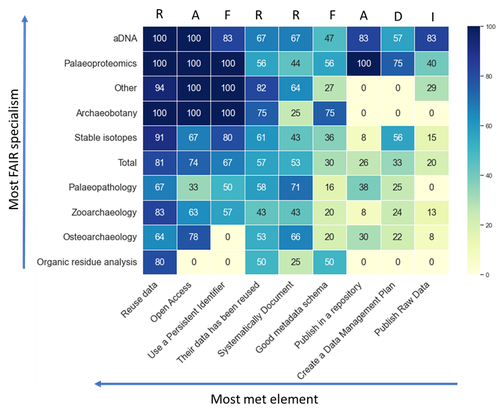

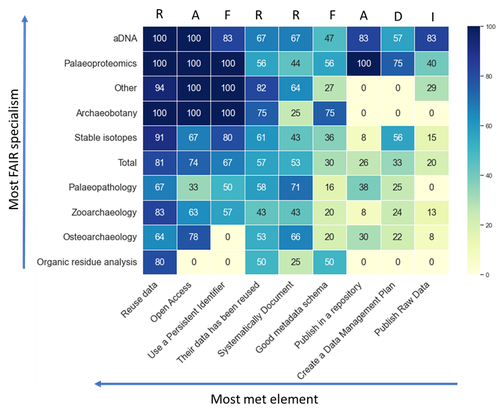

How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data ReusableLien-Talks, Alphaeus https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910FAIR data in bioarchaeology - where are we at?Recommended by Claudia Speciale based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers

The increasing reliance on digital and big data in archaeology is pushing the scientific community more and more to reconsider their storing and use [1, 2]. Furthermore, the openness and findability in the way these data are shared represent a key matter for the growth of the discipline, especially in the case of bioarchaeology and archaeological sciences [3]. In this paper, [4] the author presents the result of a survey targeted on UK bioarchaeologists and then extended worldwide. The paper maintains the structure of a report as it was intended for the conference it was part of (CAA 2023, Amsterdam) but it represents the first public outcome of an inquiry on the bioarchaeological scientific community. A reflection on ourselves and our own practices. Are all the disciplines adhering to the same policies? Do any bioarchaeologist use the same protocols and formats? Are there any differences in between the domains? Is the Needs Analysis fulfilling the questions? The results, obtained through an accurate screening to avoid distortions, are creating an intriguing picture on the current state of "fairness" and highlighting how Institutions' rules and policies can and should indicate the correct workflow to follow. In the end, the wide application of the FAIR principles will contribute significantly to the growth of the disciplines and to create an environment where the users are not just contributors, but primary beneficiaries of the system. [1] Huggett j. (2020). Is Big Digital Data Different? Towards a New Archaeological Paradigm, Journal of Field Archaeology, 45:sup1, S8-S17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2020.1713281 [2] Nicholson C., Kansa S., Gupta N. and Fernandez R. (2023). Will It Ever Be FAIR?: Making Archaeological Data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Advances in Archaeological Practice 11 (1): 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2022.40 [3] Plomp E., Stantis C., James H.F., Cheung C., Snoeck C., Kootker L., Kharobi A., Borges C., Reynaga D.K.M., Pospieszny Ł., Fulminante, F., Stevens, R., Alaica, A. K., Becker, A., de Rochefort, X. and Salesse, K. (2022). The IsoArcH initiative: Working towards an open and collaborative isotope data culture in bioarchaeology. Data in brief, 45, p.108595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2022.108595 [4] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable. Zenodo, 8139910, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910 | How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable | Lien-Talks, Alphaeus | <p>Bioarchaeology, which encompasses the study of ancient DNA, osteoarchaeology, paleopathology, palaeoproteomics, stable isotopes, and zooarchaeology, is generating an ever-increasing volume of data as a result of advancements in molecular biolog... |  | Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Zooarchaeology | Claudia Speciale | 2023-07-12 19:12:44 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer