based on reviews by Mario Zimmerman and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Mario Zimmerman and 2 anonymous reviewers

The advent of biomolecular methods has certainly increased our overall comprehension of archaeological societies. One of the materials of choice to perform ancient DNA or proteomics analyses is dental calculus[1,2], a mineralised biofilm formed during the life of one individual. Research conducted in the past few decades has demonstrated the potential of dental calculus to retrieve information about past societies health[3–6], diet[7–11], and more recently, as a putative proxy for isotopic analyses[12].

Based on a proof-of-concept previously published by their team[13], Bartholdy and collaborators’ paper presents the identification of compounds and their secondary metabolites derived from consumed plants in individuals from a XIXth century rural Dutch archaeological deposit[14]. Sørensen indeed demonstrated that drug intake is recorded in dental calculus, which are mineralised biofilms that can encapsulate drug compounds long after the latter are no longer detectable in blood. The liquid-chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)-based method developed showed the potential for archaeological applications[13].

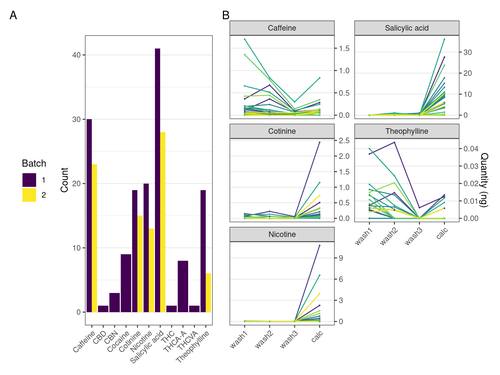

Bartholdy et al. utilised the developed LC-MS/MS method to 41 buried individuals, most of them bearing pipe notches on their teeth, from the cemetery of the 19th rural settlement of Middenbeemster, the Netherlands. Along with dental calculus sampling and analysis, they undertook the skeletal and dental examination of all of the specimens in order to assess sex, age-at-death, and pathology on the two tissues. The results obtained on the dental calculus of the sampled individuals show probable consumption of tea, coffee and tobacco indicated by the detection of the various plant compounds and associated metabolites (caffeine, nicotine and salicylic acid, amongst others).

The authors were able to place their results in perspective and propose several interpretations concerning the ingestion of plant-derived products, their survival in dental calculus and the importance of their findings for our overall comprehension of health and habits of the XIXth c. Dutch population. The paper is well-written and accessible to a non-specialist audience, maximising the impact of their study. I personally really enjoyed handling this manuscript that is not only a good piece of scientific literature but also a pleasant read, the reason why I warmly recommend this paper to be accessible through PCI Archaeology.

References

1. Fagernäs, Z. and Warinner, C. (2023) Dental Calculus. in Handbook of Archaeological Sciences 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119592112.ch28

2. Wright, S. L., Dobney, K. & Weyrich, L. S. (2021) Advancing and refining archaeological dental calculus research using multiomic frameworks. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 7, 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2021.1882122

3. Fotakis, A. K. et al. (2020) Multi-omic detection of Mycobacterium leprae in archaeological human dental calculus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 375, 20190584. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0584

4. Warinner, C. et al. (2014) Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nat. Genet. 46, 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2906

5. Weyrich, L. S. et al. (2017) Neanderthal behaviour, diet, and disease inferred from ancient DNA in dental calculus. Nature 544, 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21674

6. Jersie-Christensen, R. R. et al. (2018) Quantitative metaproteomics of medieval dental calculus reveals individual oral health status. Nat. Commun. 9, 4744. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07148-3

7. Hendy, J. et al. (2018) Proteomic evidence of dietary sources in ancient dental calculus. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.0977

8. Wilkin, S. et al. (2020) Dairy pastoralism sustained eastern Eurasian steppe populations for 5,000 years. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1120-y

9. Bleasdale, M. et al. (2021) Ancient proteins provide evidence of dairy consumption in eastern Africa. Nat. Commun. 12, 632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20682-3

10. Warinner, C. et al. (2014) Direct evidence of milk consumption from ancient human dental calculus. Sci. Rep. 4, 7104. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07104

11. Buckley, S., Usai, D., Jakob, T., Radini, A. and Hardy, K. (2014) Dental Calculus Reveals Unique Insights into Food Items, Cooking and Plant Processing in Prehistoric Central Sudan. PLoS One 9, e100808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100808

12. Salazar-García, D. C., Warinner, C., Eerkens, J. W. and Henry, A. G. (2023) The Potential of Dental Calculus as a Novel Source of Biological Isotopic Data. in Exploring Human Behavior Through Isotope Analysis: Applications in Archaeological Research (eds. Beasley, M. M. & Somerville, A. D.) 125–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32268-6_6

13. Sørensen, L. K., Hasselstrøm, J. B., Larsen, L. S. and Bindslev, D. A. (2021) Entrapment of drugs in dental calculus - Detection validation based on test results from post-mortem investigations. Forensic Sci. Int. 319, 110647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110647

14. Bartholdy, Bjørn Peare, Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B., Sørensen, Lambert K., Casna, Maia, Hoogland, Menno, Historisch Genootschap Beemster and Henry, Amanda G. (2023) Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch population, Zenodo, 7649150, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7649150

The authors have address all my concerns and I recommend the article for publication.

DOI or URL of the preprint: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8199885

Version of the preprint: 3

Dear Reviewers, Louise,

Thank you for taking the time to review this preprint; it has greatly improved the scientific component and clarity. We are very pleased with the overall positive feedback, and we recognise that this takes time from your busy schedules. We greatly appreciate it!

We have addressed all of the comments. Most of the recommendations have been incorporated into the revised manuscript, barring a few minor details which were either not feasible or conflicted with our personal preferences (more details in the response to the specific comments). We restricted the length of the added components due to the fact that the discussion is already a bit on the long side.

The tracked changes document represents the git diff output for the paper.tex file (which was used to generate the PDF manuscript). Removed items are marked in red and new additions are marked in green.

Best,

Bjorn (on behalf of co-authors)

, posted 12 Sep 2023, validated 12 Sep 2023

, posted 12 Sep 2023, validated 12 Sep 2023The manuscript brought forth by Bartholdy et al. represents an important step forward in the study

of secondary metabolite residues in archaeological human remains. Building on their own team’s

recent advances as well as research published by other scholarly groups, the authors address new

questions – the correlation between the detection of different compounds, or the correlation

between pathological conditions and residue signals – while at the same time increasing the time

depth for the application of a protocol previously only tested on contemporary samples. While

contamination remains an issue to be aware of, Bartholdy et al. also provide suggestions as to how

to distinguish diagenetic impacts and lab contaminants from metabolomic signals related to human

substance consumption.

Specific suggestions for improvements:

This is an inteteresting article building on previous studies on alkaloid preservation in dental calculus. It will make an important contribution to the growing field of dental calculus studies, and I recommend it be published in a journal. The study is well-designed and reaches some interesting conclusions regarding this 19th century rural population from the Netherlands. I don't have any major critiques or criticisms.

Bartholdy et al. investigate the utility of a new method for detecting alkaloids, previously validated using recently deceased individuals, on archaeological dental calculus. The manuscript is well-written, the methods are sound, and the conclusions are relevant to the data presented. I only have minor comments for further clarification of the manuscript as detailed below.

Throughout the manuscript, the authors state that “well-preserved” individuals have higher yields of substances of interest. It would be helpful to briefly define what they mean by well preserved.

L48: “The relation to plasma is why there is often a close correlation between the presence (not concentration) of drugs in oral fluid and blood” This sentence was a little confusing to me, can the authors clarify?

L82: “To reduce the number of potentially confounding factors to account for in the analysis, we preferentially selected males from the middle adult age category” Can the authors expand on this choice? Is there previous literature that details how age/biological sex are confounding factors?

L98: Is this sentence missing “allow for statistical analysis”?

L196: Here it states that the accuracy of the method is 59.3% but in the abstract, it is 60% if I’m interpreting these statements correctly?

L206: Please match these numbers to the same rounding point as found in Table 2 (e.g., 0.982 should be 0.98? 0.507 should be 0.51?)

Table 2: In general, this table asks the reader to do much of the work to pull out the important points. Maybe highlight those correlations that are most interesting?

Figure 3: Again, this figure is a little hard to interpret. From my understanding of the text, the scatter plots are supposed to illustrate the correlation between weight and quantity of the substance – are there corresponding statistics that could be shown (e.g., R2 values?). Similarly, are the amounts shown in the violin plots statistically different from one another?

Figure 4: Similar issue here, distinguishing differences between the sizes and color gradient of the circles are a little difficult for me to see. Could again highlight important correlations with some statistics maybe?

L269: “salicilyc acid is a very mobile organic acid” Can you expand on this?

L295: “It has been shown that, while abundant in opium, morphine degrades rapidly…” This sentence seems to be missing a statement. What is abundant in opium?

L308: “We suspect that the original detection of cocaine was a result of lab contamination during analysis” Was this also detected in batch one (which was presumed contaminated)?

L360: “be around 59.3%” Again, should this be 60%?