“What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery” by P. Boissinot (1) is a timely contribution to broader theoretical reflections on classification and ordering practices in archaeology, including type-construction and justification. Boissinot rightly reminds us that engagement with the type concept always touches upon the uneasy relationship between the abstract and the concrete, alternatively cast as the ongoing struggle in knowledge production between idealization and particularization. Types are always abstract and as such both ‘more’ and ‘less’ than the concrete objects they refer to. They are ‘more’ because they establish a higher-order identity of variously heterogeneous, concrete objects and they are ‘less’ because they necessarily reduce the richness of the concrete and often erase it altogether. The confusion that types evoke in archaeology and elsewhere has therefore a lot to do with the fact that types are simply not spatiotemporally distinct particulars. As abstract entities, types so almost automatically re-introduce the question of universalism but they do not decide this question, and Boissinot also tentatively rejects such ambitions. In fact, with Boissinot (1) it may be said that universality is often precisely confused with idealization, which is indispensable to all archaeological ordering practices.

Idealization, increasingly recognized as an important epistemic operation in science (2, 3), paradoxically revolves around the deliberate misrepresentation of the empirical systems being studied, with models being the paradigm cases (4). Models can go so far as to assume something strictly false about the phenomena under consideration in order to advance their epistemic goals. In the words of Angela Potochnik (5), ‘the role of idealization in securing understanding distances understanding from truth but […] this understanding nonetheless gives rise to scientific knowledge’. The affinity especially to models may in part explain why types are so controversial and are often outright rejected as ‘real’ or ‘useful’ by those who only recognize the existence of concrete particulars (nominalism). As confederates of the abstract, types thus join the ranks of mathematics and geometry, which the author identifies as prototypical abstract systems. Definitions are also abstract. According to Boissinot (1), they delineate a ‘position of limits’, and the precision and rigorousness they bring comes at the cost of subjectivity. This unites definitions and types, as both can be precise and clear-cut but they can never be strictly singular or without alternative – in order to do so, they must rely on yet another higher-order system of external standards, and so ad infinitum.

Boissinot (1) advocates a mathematical and thus by definition abstract approach to archaeological type-thinking in the realm of pottery, as the abstractness of this approach affords relatively rigorous description based on the rules of geometry. Importantly, this choice is not a mysterious a priori rooted in questionable ideas about the supposed superiority of such an approach but rather is the consequence of a careful theoretical exploration of the particularities (domain-specificities) of pottery as a category of human practice and materiality. The abstract thus meets the concrete again: objects of pottery, in sharp contrast to stone artefacts for example, are the product of additive processes. These processes, moreover, depend on the ‘fusion’ of plastic materials and the subsequent fixation of the resulting configuration through firing (processes which, strictly speaking, remove material, such as stretching, appear to be secondary vis-à-vis global shape properties). Because of this overriding ‘fusion’ of pottery, the identification of parts, functional or otherwise, is always problematic and indeterminate to some extent. As products of fusion, parts and wholes represent an integrated unity, and this distinguishes pottery from other technologies, especially machines. The consequence is that the presence or absence of parts and their measurements may not be a privileged locus of type-construction as they are in some biological contexts for example. The identity of pottery objects is then generally bound to their fusion. As a ‘plastic montage’ rather than an assembly of parts, individual parts cannot simply be replaced without threatening the identity of the whole. Although pottery can and must sometimes be repaired, this renders its objects broadly morpho-static (‘restricted plasticity’) rather than morpho-dynamic, which is a condition proper to other material objects such as lithic (use and reworking) and metal artefacts (deformation) but plays out in different ways there. This has a number of important implications, namely that general shape and form properties may be expected to hold much more relevant information than in technological contexts characterized by basal modularity or morpho-dynamics.

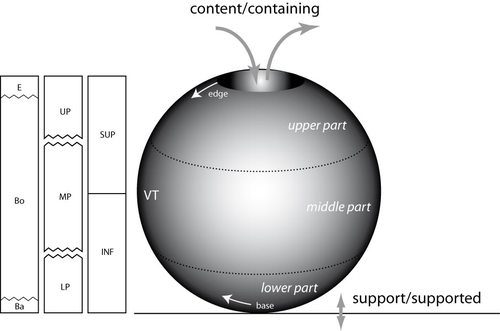

It is no coincidence that ‘fusion’ is also emphasized by Stephen C. Pepper (6) as a key category of what he calls contextualism. Fusion for Pepper pays dividends to the interpenetration of different parts and relations, and points to a quality of wholes which cannot be reduced any further and integrates the details into a ‘more’. Pepper maintains that ‘fusion, in other words, is an agency of simplification and organization’ – it is the ‘ultimate cosmic determinator of a unit’ (p. 243-244, emphasis added). This provides metaphysical reasons to look at pottery from a whole-centric perspective and to foreground the agency of its materiality. This is precisely what Boissinot (1) does when he, inspired by the great techno-anthropologist François Sigaut (7), gestures towards the fact that elementarily a pot is ‘useful for containing’. He thereby draws attention not to the function of pottery objects but to what pottery as material objects do by means of their material agency: they disclose a purposive tension between content and container, the carrier and carried as well as inclusion and exclusion, which can also be understood as material ‘forces’ exerted upon whatever is to be contained. This, and not an emic reading of past pottery use, leads to basic qualitative distinctions between open and closed vessels following Anna O. Shepard’s (8) three basic pottery categories: unrestricted, restricted, and necked openings. These distinctions are not merely intuitive but attest to the object-specificity of pottery as fused matter.

This fused dimension of pottery also leads to a recognition that shapes have geometric properties that emerge from the forced fusion of the plastic material worked, and Boissinot (1) suggests that curvature is the most prominent of such features, which can therefore be used to describe ‘pure’ pottery forms and compare abstract within-pottery differences. A careful mathematical theorization of curvature in the context of pottery technology, following George D. Birkhoff (9), in this way allows to formally distinguish four types of ‘geometric curves’ whose configuration may serve as a basis for archaeological object grouping. The idealization involved in this proposal is not accidental but deliberately instrumental – it reminds us that type-thinking in archaeology cannot escape the abstract. It is notable here that the author does not suggest to simply subject total pottery form to some sort of geometric-morphometric analysis but develops a proposal that foregrounds a limited range of whole-based geometric properties (in contrast to part-based) anchored in general considerations as to the material specificity of pottery as quasi-species of objects.

As Boissinot (1) notes himself, this amounts to a ‘naturalization’ of archaeological artefacts and offers somewhat of an alternative (a third way) to the old discussion between disinterested form analysis and functional (and thus often theory-dependent) artefact groupings. He thereby effectively rejects both of these classic positions because the first ignores the particularities of pottery and the real function of artefacts is in most cases archaeologically inaccessible. In this way, some clear distance is established to both ethnoarchaeology and thing studies as a project. Attending to the ‘discipline of things’ proposal by Bjørnar Olsen and others (10, 11), and by drawing on his earlier work (12), Boissinot interestingly notes that archaeology – never dealing with ‘complete societies’ – could only be ‘deficient’. This has mainly to do with the underdetermination of object function by the archaeological record (and the confusion between function and functionality) as outlined by the author. It seems crucial in this context that Boissinot does not simply query ‘What is a thing?’ as other thing-theorists have previously done, but emphatically turns this question into ‘In what way is it not the same as something else?’. He here of course comes close to Olsen’s In Defense of Things insofar as the ‘mode of being’ or the ‘ontology’ of things is centred. What appears different, however, is the emphasis on plurality and within-thing heterogeneity on the level of abstract wholes. With Boissinot, we always have to speak of ontologies and modes of being and those are linked to different kinds of things and their material specificities. Theorizing and idealizing these specificities are considered central tasks and goals of archaeological classification and typology. As such, this position provides an interesting alternative to computational big-data (the-more-the-better) approaches to form and functionally grounded type-thinking, yet it clearly takes side in the debate between empirical and theoretical type-construction as essential object-specific properties in the sense of Boissinot (1) cannot be deduced in a purely data-driven fashion.

Boissinot’s proposal to re-think archaeological types from the perspective of different species of archaeological objects and their abstract material specificities is thought-provoking and we cannot stop wondering what fruits such interrogations would bear in relation to other kinds of objects such as lithics, metal artefacts, glass, and so forth. In addition, such meta-groupings are inherently problematic themselves, and they thus re-introduce old challenges as to how to separate the relevant super-wholes, technological genesis being an often-invoked candidate discriminator. The latter may suggest that we cannot but ultimately circle back on the human context of archaeological objects, even if we, for both theoretical and epistemological reasons, wish to embark on strictly object-oriented archaeologies in order to emancipate ourselves from the ‘contamination’ of language and in-built assumptions.

Bibliography

1. Boissinot, P. (2024). What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery, Zenodo, 7429330, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433

2. Fletcher, S.C., Palacios, P., Ruetsche, L., Shech, E. (2019). Infinite idealizations in science: an introduction. Synthese 196, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02069-6

3. Potochnik, A. (2017). Idealization and the aims of science (University of Chicago Press). https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226507194.001.0001

4. J. Winkelmann, J. (2023). On Idealizations and Models in Science Education. Sci & Educ 32, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00291-2

5. Potochnik, A. (2020). Idealization and Many Aims. Philosophy of Science 87, 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1086/710622

6. Pepper S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (University of California Press).

7. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l’analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d’études Technologiques En Préhistoire. Bilan et Perspectives (Association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques), pp. 21–34.

8. Shepard, A. O. (1956). Ceramics for the Archeologist (Carnegie Institution of Washington n° 609).

9. Birkhoff G. D. (1933). Aesthetic Measure (Harvard University Press).

10. Olsen, B. (2010). In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects (AltaMira Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/ept014

11. Olsen, B., Shanks, M., Webmoor, T., Witmore, C. (2012). Archaeology: the discipline of things (University of California Press). https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520954007

12. Boissinot, P. (2011). “Comment sommes-nous déficients ?” in L’archéologie Comme Discipline ? (Le Seuil), pp. 265–308.

DOI or URL of the preprint: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7429330

Version of the preprint: 1

Dear reviewers, thank you very much for your careful and, most of the time, very relevant reading.

In particular, I've written a real introduction in which I develop some of the questions that were suggested to me, multiplying their importance by 3. I've gone into more detail about the state of the art (thanks for the reading I've been able to do thanks to you, which can be found in the bibliography). For example, I introduced the concept of affordance, gave a few details about (French) authors such as Leroi-Gourhan, Simondon and Gardin, and clarified some concepts. There's also a conclusion that didn't exist before.

The text has been revised by an English-speaking professional. I made a few ad hoc clarifications.

Thank you also, in addition to the criticisms, for the interest that most of you have shown in my essay.

You can find attached the manuscript with additions in yellow.

, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak

, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , posted 29 Mar 2023, validated 29 Mar 2023

, posted 29 Mar 2023, validated 29 Mar 2023Dear colleague,

many thanks for submitting your draft chapter and going along with our PCI-based review process. As you will see from the reviewers’ comments, your chapter is considered a valuable contribution to our planned volume, packed with useful observations, arguments and insight.

Both reviewers have made useful comments and offer some critique that should be taken into consideration before publication. Their observations are extremely useful and should help in further improving the chapter. As both reviewers’ point out, a structural revision of the introduction and a clearer statement of the goal, approach and contribution of the chapter would be beneficial. I would suggest to also add a short recap/summary of the key points at the end of the chapter.

The reviewers’ comments are listed below.

I have here taken the liberty to add a few points to their comments as you may want to consider them in your revisions as well:

p. 1, “comprehensive perspectives” of the social sciences: perhaps consider to flag up the notion of “holism”/“holistic” perspectives in this context already early as well, as this is later in some way addressed in your mereological discussion (holism would relate to whole-centrism, as opposed to part-centrism, for example)

p. 2 abstract vs. concrete: to clarify this point and to avoid misunderstandings, I may be useful to refer to G. Simondon’s influential distinction between ‘abstract’ and ‘concrete’ objects, which has recently made an impact on archaeological research as well

p. 1., “Finally, rather than imposing a very precise definition of the notion of “type” from the outset, we shall consider it initially as equivalent to that of “category” or “class”, …”: I think this needs to be explained/justified a bit more as these distinctions are crucial for some and conflating them is sometimes argued to lie at the heart of the problem

p. 1ff., Artefact identity and classification section: I believe that this section could benefit from some brief notes on artefacts and copying vis-à-vis industrial and non-industrial objects, leading to a general discussion on the “replicability” of (artefactual) form. Schmücker (2020), for example, discusses the condition of replicability with regard to ‘unicale’ vs. ‘replicable’ artefacts (text attached below) and some of these points may be of relevance here

p. 3, “The matter is even more complex when the function understood by the manufacturers differs from that of the users, for example when the objects cross socio-cultural frontiers, or when the opportunity or the circumstances seem to impose themselves”: it may be useful to briefly mention and discuss ‘affordances’ in this context as they are now explicitly invoked to solve part of this problem (see for example Jung 2020: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/pz-2020-0026/html?lang=de); perhaps especially so since Sigaut seems to have a strong view as to the utility of the concept in understanding object instrumentalization

p. 3, “It must then be admitted that the identity of the artifacts remains largely undetermined”: do you really mean ‘undertermined’ or do you rather mean ‘underdetermined’?

p. 3ff., The essential properties of (archaeological) pottery: at the latest here but probably earlier, I would suggest to provide some sort of a discussion of the concept of ‘form’. What definition of form do you have in mind here/refer to? The understanding and foregrounding of form often reflects a Platonian/Aristotelian view of reality, frequently mirrored in talk about ‘ideals’. This may be important to highlight as the distinction of ‘abstract’ and ‘concrete’ as well as the relationship between ‘form’ and ‘matter’ might hinge/rely on this background

p. 5: perhaps consider to add ‘synthesis’ as a key feature of pottery form, calling for a synthetic approach (whole-centric) rather than an analytical (part-centric), and the tensions and problems arising from this

p. 12ff, Point of view from nowhere, universals and culturalism: note that Alison Wylie and other philosophers of science also speak of a ‘view from nowhere’ but with regard to theory-laden observation etc.; it may be useful to mention this and distinguish your use of the label from theirs. I would also suggest to briefly refer to the problem of alterity (alterité) as culturalism and the emic dimension of artefact form, esp. ‘function’, are discussed

All of this being said, this is a potentially strong chapter that will fit beautifully into the volume – so thank you again for your submission.

We are looking forward to seeing your revised version in due time.

Best wishes,

Shumon

Download recommender's annotations-The title reflects clearly the content of the article.

-The abstract is concise and presents the main findings of the study.

-The introduction (I guess): I find the first part of the introduction (until ‘before we focus on the specificity’) a bit more confused that the rest of the article. Indeed, it is not really discussed in detail afterwards. The notions which are discussed are very interesting so, in my opinion, either the author has to develop a bit more, either he has to reduce. The rest of the introduction is extremely interesting and sum up the previous notions regarding the definition of form and functions. The author mentions that he will not deal with the function, just the form.

-The core of the article and discussion: this very interesting and brilliant article is much more like an ‘essay’ than presentation of new data. It is a thought about the classification/identification of the forms (how to name them, how to distinguish them, etc.) by the archaeologists but from a philosophical/epistemological perspective. The author has decided to left apart the connection between form and function to really focus of the description of the form and the ways to do it (volumes, mereology, etc.). I wonder why the work done by Gardin is not discussed. I guess that the author associates him to the ‘computer’ approach with the development of mathematics.

Personally I would be interested to know what the author thinks about the platform ONICER https://www.onicer.org/accueil/introduction/les-typologies/ set up by Xavier Deru in this attempt to record and to create a kind of “universal” index for the form.

General Assessment

The intended audience, and the main aims of this paper are difficult to follow. The author proposes to bring mathematical approaches to the characterisation of form to traditional archaeological (social science-based) methods of typology-building. This, they argue, sets up an opposition between abstract and concrete (ontological and semantic) that can be bridged by using an “onto-epistemo-semantic” approach. I believe that both the problem addressed and the proposed methods and approaches used could be explained to the reader far more clearly, at the start and at the end of the article. A broader readership could also be reached if the author were to unpack excessive theoretical terminology using more accessible language.

The main strengths of this article arise in discrete sections of discussion dispersed throughout. It provides a solid introduction to some of the relevant theories behind object form, a sophisticated discussion regarding the unique materiality of pottery vessels (e.g. as fusions rather than assemblies), and integrates various inter-disciplinary perspectives (mathematical, artistic, phenomenological etc.) that have rarely been brought to these discussions. These are supported by useful figures.

Two of the primary arguments made are that:

1) Classification based on form is inherently subjective: this has been widely accepted by ceramicists across the discipline for a long time. Archaeological 'types', by and large, are not in themselves designed to reflect past realities, but to enable the ceramicist to pursue their own research objectives (whether technological, functional, or chronological).

2) Pottery form as an “aim” or an “idea” of the potter rather than a concrete reality: this has also been a long-standing topic within archaeological craft analyses, usually discussed under the guise of the craftsperson’s “mental template” (after Deetz 1967) prior to production, as distinguished from the realised form following production.

It is for these reasons that I hold reservations about the originality of the research in this article. The author overlooks some core philosophical/anthropological approaches to object form and typological/classification practice. Two major publications that cover similar ground, for instance, are Daniel Miller’s (1985) Artefacts as Categories, and William Adams and Ernest Adams’ (1991) Archaeological Typology and Practical Reality. There are also important publications on geometric approaches to pottery classification that should be referenced (see specific comments below).

By integrating some of these wider discussions, this paper might become a very useful overview covering key theories of and approaches to pottery form. To expand beyond this in terms of rigour and originality, I would suggest two main developments:

· To integrate a case study type/assemblage: the structure of the piece would benefit enormously from being supported by a case study against which the abstract ideas are developed.

· To explain clearly the methodological applicability of the findings. How could I, as a ceramicist, bring the theoretical perspectives discussed in this article to bear on my own methodological practices of form recognition/typology building?

Note on writing style

The writing requires revision. Numerous grammatical errors and lack of clarity in meaning, largely due to overly complex word choices. I did not pick up on these instances systematically, and would suggest editing from someone with full professional proficiency in English if this paper were to be prepared for publication. The issues with grammar, phrasing, and word choice may result in some of the subtlety/complexity of the paper’s argument being lost.

Specific Comments on each section

Since no page numbers were provided with this preprint, I have chosen to structure specific comments by section:

Introduction

The introductory paragraph presents the reader with a host of theoretical terms with little attempt to unpack them for a broader non-specialist audience. After reading through several times, I am still unclear as to who precisely the audience for this paper is and what its main contribution(s) to the field are. This should be spelled out clearly.

‘Artefact identity and classification’

There are some really interesting points scattered throughout this section:

- Questions of the “identical” and how this differs between industrial and non-industrial archaeological contexts.

- The differences developed between “qualitative identity” and “sortal identity”.

- The difference between societal recognition of objects according to “spatial configuration” rather than “their microscopic nature”.

- The slippage of an object’s functional identity during its use-life, using the example of the author’s bedside table.

These points are combined to state that “the identity of the artefacts remains largely undetermined.” While this is of course true to an extent, the author should show further consideration of the contextual/relational approaches developed in the last few decades, which do in fact seek to take into account those issues outlined above.

‘The essential properties of (archaeological) pottery’

Taking on board Birkhoff’s “visual contour”, where focus is placed on specific “characteristic points” rather than entire vessel profiles and cross-sections. An interesting point of reference, but such an approach has a heavy focus on the aesthetic qualities of vessels. This is stated as a way of “naturalizing” an object; it is unclear what ‘naturalizing’ means here, or why it is necessary?

Very interesting discussion of the “container/content” and “carrier/carried” relationship. Qualification of this relationship is given in reference to the preposition “on”. Specific examples should be given to explain this linguistic point to the reader.

A sophisticated discussion of pots as a “fusion”, therefore different to other objects which tend to be an “assembly of different parts”. This is, conceptually, very interesting in terms of the irreversibility and lack of adaptability of a vessel’s form.

Important critique of ceramicists who see the production of typological plates alone as the outcome of their research – described as “epistemic reduction”. Would like to see this idea developed further.

“plural particulars” – this explanation confused me. Feels like more clarity is needed.

‘Measuring operations and mereology’

Interesting introduction to ideas of ‘mereology’ – not something I have seen in archaeological classification before and well worth theoretical discussion here.

Birkhoff’s ideas of visual contours are introduced again, this time with a methodology of classification in four points. However, what must be kept in mind is the how Birkhoff’s ideas of visual contours are modernist in terms of how they privilege visual consumption over the other senses. This is to some extent acknowledged by the author (e.g. “recalls Renaissance research on the proportions of the human body”), but could be placed better within emic conceptions of vessel classification.

Effective use of Anne Shephard’s work, an influential formative ceramicist. It would, however, have been useful to follow this thread through a bit further. What of the general analyses of ceramics and typology-making that have emerged since (Rice 1987; Orton and Hughes 2014)? These are the most widely read introductory ceramic analysis textbooks– do they discuss these topics?

This brings the author onto a key argument: “how unsatisfactory the commonly used names are.” While I agree on the problems of inconsistency in the use of traditional pottery terminology, this is not new or original observation. The author does draw out some core arguments for and against the use of ‘neutral’ geometric typologies, using Shephard’s (1956) work as a basis. There has, however, been a stream of discussion on this very topic over the last 50 years which is overlooked here. This includes, but is certainly not limited to:

Ericson, J. E., and Stickel, E. G. (1973) A Proposed Classification System for Ceramics. World Archaeology, 4(3): p.357-367.

Kempton, W. 1981. The Folk Classification of Ceramics. New York: Academic Press.

Miller, D. 1985. Artefacts as Categories. A Study of Ceramic Variability in Central India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Riemer, H. 1997. Form und Funktion. Zur systematischen Aufnahme und vergleichenden Analyse prähistorischer Gefäßkeramik. Archäologische Informationen, 20: p.117-131.

Inclusion of some of these sources would no doubt strengthen the discussion in this section.

‘Point of view from nowhere, universals and culturalism’

This concluding section is confusing. A range of ideas, from metaphysics (van Inwagen 1990) to phenomenology (Husserl 1984), are introduced without being fully developed and integrated. It feels like to core arguments and aims of the article are not fully unaddressed, or are discussed far too implicitly.

The last paragraph introduces the concept of type/form as an “idea” or an “aim” as much as a concrete reality. How does this differ from the notion of a “mental template” (after Deetz 1967), which has influenced a wide range of archaeological craft analyses ever since?