RIEDE Felix

- CLIOARCH, Aarhus University, Højbjerg, Denmark

- Europe, Geoarchaeology, Lithic technology, Mesolithic, Middle Palaeolithic, Paleoenvironment, Peopling, Upper Palaeolithic

- recommender

Recommendations: 12

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 12

The Physics and Metaphysics of Classification in Archaeology

The “Beast Within” – Querying the (Cultural Evolutionary) Status of Types in Archaeology

Recommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Edward B. Banning and 2 anonymous reviewers“On the Physics and Metaphysics of Classification in Archaeology” by M. Okumura and A.G.M. Araujo (1) is a welcome contribution to our upcoming edited volume on type-thinking and the uses and misuses of archaeological typologies. Questions of type-delineation and classification of archaeological materials have recently re-emerged as key arenas of scholarly attention and interrogation (2–4), as many researchers have turned to a matured field of cultural evolutionary studies (5–7) and as fine-grained archaeological data and novel computational-quantitative methods have becomes increasingly available in recent years (8, 9). Re-assessing the utility and significance of traditional archaeological types has also become pertinent as macro-scale approaches to the past have grown progressive to the centre of the discipline (10, 11), promising not only to ‘re-do’ typology ‘from the ground up’, but also to put types and typological systems to novel and powerful use, and in the process illuminate the many understudied large-scale dynamics of human cultural evolution which are so critical to understanding our species’ venture on this planet. As such, the promise is colossal yet it requires a solid analytical base, as many have insisted (e.g., 12). Types are often identified as such foundational analytical units, and much therefore hinges on the robust identification and differentiation of types within the archaeological record. Typo-praxis – the practice of delineating and constructing types and to harness them to learn about the archaeological record – is therefore also increasingly seen as a key ingredient of what Hussain and Soressi (13) have dubbed the ‘basic science’ claim of lithic research within human origins or broader (deep-time) evolutionary studies.

The stakes are accordingly incredibly high, yet as Okumura and Araujo point out there is still no need to ‘re-invent the wheel’ as there is a rich literature on classification and systematics in the biological sciences, from which archaeologists can draw and benefit. Some of this literature was indeed already referenced by some archaeologists between the 1960s and early 2000s when first attempts were undertaken to integrate Darwinian evolutionary theory into processual archaeological practice (14, 15). It may be argued that much of this literature and its insights – including its many conceptual and terminological clarifications – have been forgotten or sidelined in archaeology primarily because the field has witnessed a pronounced ‘cultural turn’ beginning in the early 2000s, with even processualists expanding their research portfolio to include what was previously considered post-processual terrain (16, 17). Michelle Hegmon’s (16) ‘processualism plus’ was perhaps the most emphatic expression of this trajectory within the influential Anglo-American segments of the profession. Okumura and Araujo are therefore to be applauded for their attempt to draw attention again to this literature in an effort to re-activate it for contemporary research efforts at the intersection of cultural evolutionary and computational archaeology. Decisions need to be made on the way, of course, and the authors defend a theory-guided (and largely theory-driven) approach, for example insisting on the importance of understanding the metaphysical status of types as arbitrary kinds. Their chapter is hence also a contribution (some may say intervention) to the long-standing tension between the tyranny of data vs. the tyranny of theory in type-construction. They clearly take side with those who argue that typo-praxis cannot evade its metaphysical nature – i.e., it will always be concerned (to some extent at least) with uncovering basic metaphysical principles of the world, even if the link between types and world is not understood as a simple mapping function. Carving the investigated archaeological realities ‘at their joints’ remains an overarching ambition from this perspective. Following Okumura and Araujo, archaeologists interested in these matters therefore cannot avoid to become part-time metaphysicians.

Okumura and Araujo’s contribution is timely and it brings key issues of debate to archaeological attention, and many of these issues tellingly overlap substantially with foundational debates in the philosophy of science (e.g. monism vs. pluralism, essentialism vs. functionalism, and so forth). Their chapter also showcases how critical (both in an enabling and limiting way) biological metaphors such as ‘species’ are (see esp. the discussion of ‘species as sets’ vs. ‘species as individuals’) for their and cognate projects. Whether such metaphors are justified in the context of human action is a longstanding point of contention, and other archaeologies – for example those with decidedly relational, ontological, and post-humanist aspirations – have developed very different optics (see e.g. 18, esp. Chapter 6). This being said, Okumura and Araujo’s contribution will be essential for those interested in (re-)learning about the ‘physics and metaphysics’ of archaeological classification and their chapter will be an excellent place to start with such engagement.

References

1. M. Okumura and A. G. M. Araujo (2024) The Physics and Metaphysics of Classification in Archaeology. Zenodo, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7515797

2. F. Riede (2017) “The ‘Bromme problem’ – notes on understanding the Federmessergruppen and Bromme culture occupation in southern Scandinavia during the Allerød and early Younger Dryas chronozones” in Problems in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Research, pp. 61–85.

3. N. Reynolds and F. Riede (2019) House of cards: cultural taxonomy and the study of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Antiquity 93, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.49

4. R. L. Lyman (2021) On the Importance of Systematics to Archaeological Research: the Covariation of Typological Diversity and Morphological Disparity. J Paleo Arch 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00077-6

5. A. Mesoudi (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences, University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/9780226520452

6. N. Creanza, O. Kolodny and M. W. Feldman (2017) Cultural evolutionary theory: How culture evolves and why it matters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 7782–7789. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620732114

7. R. Boyd and P. J. Richerson (2024) Cultural evolution: Where we have been and where we are going (maybe). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, e2322879121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2322879121

8. F. Riede, D. N. Matzig, M. Biard, P. Crombé, J. F.-L. de Pablo, F. Fontana, D. Groß, T. Hess, M. Langlais, L. Mevel, W. Mills, M. Moník, N. Naudinot, C. Posch, T. Rimkus, D. Stefański, H. Vandendriessche and S. T. Hussain (2024) A quantitative analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe. PLOS ONE 19, e0299512, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299512

9. L. Fogarty, A. Kandler, N. Creanza and M. W. Feldman (2024) Half a century of quantitative cultural evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, e2418106121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2418106121

10. A. M. Prentiss, M. J. Walsh, E. Gjesfjeld, M. Denis and T. A. Foor (2022) Cultural macroevolution in the middle to late Holocene Arctic of east Siberia and north America. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 65, 101388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101388

11. C. Perreault (2023) Guest Editorial. Antiquity 97, 1369–1380.

12. F. Riede, C. Hoggard and S. Shennan (2019) Reconciling material cultures in archaeology with genetic data requires robust cultural evolutionary taxonomies. Palgrave Commun 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0260-7

13. S. T. Hussain and M. Soressi (2021) The Technological Condition of Human Evolution: Lithic Studies as Basic Science. J Paleo Arch 4, 25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00098-1

14. R. C. Dunnell (1978) Style and Function: A Fundamental Dichotomy. American Antiquity 43, 192–202.

15. R. C. Dunnell (2002) Systematics in Prehistory, Illustrated Edition, The Blackburn Press.

16. M. Hegmon (2003) Setting Theoretical Egos Aside: Issues and Theory in North American Archaeology. American Antiquity 68, 213–243. https://doi.org/10.2307/3557078

17. R. Torrence (2001) “Hunter-gatherer technology: macro- and microscale approaches” in Hunter-Gatherers: An Interdisciplinary Perspective, Cambridge University Press.

18. C. N. Cipolla, R. Crellin and O. J. T. Harris (2024) Archaeology for today and tomorrow, Routledge.

IT- and machine learning-based methods of classification: The cooperative project ClaReNet – Classification and Representation for Networks

Humans, machines, and the classification of Celtic coinage – the ClaReNet project

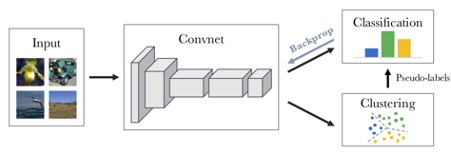

Recommended by Felix Riede, Sébastien Plutniak and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Eythan LevyThe paper entitled “IT- and machine learning-based methods of classification: The cooperative project ClaReNet – Classification and Representation for Networks” submitted by Chrisowalandis Deligio and colleagues presents the joint efforts of numismatists and data scientists in classifying a large corpus of Celtic coinage. Under the project banner “ClaReNet – Classification and Representation for Networks”, they seek to explore the possibilities and also the limits of new computational methods for classification and representation. This approach seeks to rigorously keep humans in the loop in that insights from Science and Technology Studies inform the way in which knowledge generation is monitored as part of this project. The paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology, taxonomy, classification theory, and computational approaches in archaeology.

Deligio et al. (2024) begin with a brief and pertinent research-historical outline of Celtic coin studies with a specific focus on issues of classification. They raise interesting points about how variable degrees of standardisation in manufacture – industrial versus craft production, for instance – impact our ability to derive tidy typologies. The successes and failures of particular classificatory procedures and protocols can therefore help inform on the technological contexts of various object worlds and the particularities of human practices linked to their creation. These insights and discussion are eminently case-transferrable and applies not only to coinage, which after all is rather standardised, but to practically all material culture not made by machines – a point that gels particularly well with the contribution by Lucas (2022) to be published in the same volume. Although Deligio et al. do not flag this up specifically, the very expectation that archaeological finds should neatly fall into typological categories likely related to the objects that were initially used by pioneers of the method such as Montelius (1903) to elaborate its basic principles: these were metal objects often produced in moulds and very likely by only a very small number of highly-trained craftspeople such that the production of these objects approached the standardisation seen in industrial times (Nørgaard 2018) – see also Riede’s (2023) contribution due to be published in the same volume.

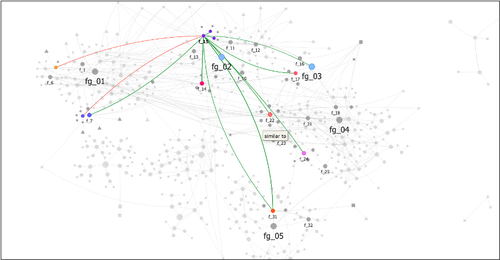

At the core of Deligio and colleagues’ contribution is the exploration of machine-aided classification that should, via automation, assist in handling the often large numbers of coins available in collections and, at times, from single sites or hoards. Specifically, the authors discuss the treatment of the remarkable coin hoard from Le Câtillon II on Jersey consisting of approximately 70,000 individual Celtic coins. They proceeded to employ several advanced supervised and unsupervised classification methods to process this stupendously large number of objects. Their contribution does not stop there, however, but also seeks to articulate the discussion of machine-aided classification with more theoretically informed perspectives on knowledge production. In line with similar approaches developed in-house at the Römisch-Germanische Kommission (Hofmann 2018; Hofmann et al. 2019; Auth et al. 2023), the authors also report on their cutely acronymed PANDA (Path Dependencies, Actor-Network and Digital Agency) methodology, which they deploy to reflect on the various actors and actants – humans, software, and hardware – that come together in the creation of this new body of knowledge. This latter impetus of the paper thus lifts the lid on the many intricate, idiosyncratic, and often quirky decisions and processes that characterise research in general and research that brings together humans and machines in particular – a concrete example of the messiness of knowledge production that commonly remains hidden behind the face of the published book or paper but which science studies have long pointed at as vital components of the scientific process itself (Latour and Woolgar 1979; Galison 1997; Shapin and Schaffer 2011). In this manner, the present contribution serves as inspiration to the many similar projects that are emerging right now in demonstrating just how vital a due integration of theory, epistemology, and method is as scholars are forging their path into a future where few if any archaeological projects do not include some element of machine-assistance.

References

Auth, Frederic, Katja Rösler, Wenke Domscheit, and Kerstin P. Hofmann. 2023. “From Paper to Byte: A Workshop Report on the Digital Transformation of Two Thing Editions.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8214563

Deligio, Chrisowalandis, Caroline von Nicolai, Markus Möller, Katja Rösler, Julia Tietz, Robin Krause, Kerstin P. Hofmann, Karsten Tolle, and David Wigg-Wolf. 2024. “IT- and Machine Learning-Based Methods of Classification: The Cooperative Project ClaReNet – Classification and Representation for Networks.” Zenodo, ver.5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7341342

Galison, Peter Louis. 1997. Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hofmann, Kerstin P. 2018. “Dingidentitäten Und Objekttransformationen. Einige Überlegungen Zur Edition von Archäologischen Funden.” In Objektepistemologien. Zum Verhältnis von Dingen Und Wissen, edited by Markus Hilgert, Kerstin P. Hofmann, and Henrike Simon, 179–215. Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 59. Berlin: Edition Topoi. https://dx.doi.org/10.17171/3-59

Hofmann, Kerstin P., Susanne Grunwald, Franziska Lang, Ulrike Peter, Katja Rösler, Louise Rokohl, Stefan Schreiber, Karsten Tolle, and David Wigg-Wolf. 2019. “Ding-Editionen. Vom Archäologischen (Be-)Fund Übers Corpus Ins Netz.” E-Forschungsberichte des DAI 2019/2. E-Forschungsberichte Des DAI. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2236/6674

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. 1979. Laboratory Life: The Social Construction of Scientific Facts. Laboratory Life : The Social Construction of Scientific Facts. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lucas, Gavin. 2022. “Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7622162

Montelius, Gustaf Oscar Augustin. 1903. Die Typologische Methode. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wicksell.

Nørgaard, Heide Wrobel. 2018. Bronze Age Metalwork: Techniques and Traditions in the Nordic Bronze Age 1500-1100 BC. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology.

Riede, Felix. 2023. “The Role of Heritage Databases in Typological Reification: A Case Study from the Final Palaeolithic of Southern Scandinavia.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8372671

Shapin, Steven, and Simon Schaffer. 2011. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times.

The Postmodern Predicament of Type-Thinking in Archaeology

Recommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Gavin Lucas, Miguel John Versluys and Anna S. Beck“Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times” by A. Ribeiro (1) offers some timely, critical and creative reflections on the manifold struggles of and disappointments in type-thinking and typological approaches in recent archaeological scholarship. Ribeiro insightfully situates what has been identified as a “crisis” in archaeological typo-praxis in the historical conditions of postmodernity and late capitalism themselves. The author thereby attempts what he himself considers “quite hard”, namely “to understand the current Zeitgeist and how it affects how we think and do archaeology” (p. 4). This provides a sort of historical epistemology of the present which can of course only be preliminary and incomplete as it crystallizes, takes shape, and transforms as we write these lines, is available only in fragments and hints, and is generally difficult to talk about and describe as we (the author included) lack critical distance – present-day archaeologists and fellow academics are both enfolded in postmodernity and continue to contribute to its logics and trajectories. Ribeiro’s key argument is provocative as it is interesting: he contends that archaeologists’ difficulties of coming to terms with types and typologies – staple knowledge practices of the discipline ever since – are a symptom of the changing cultural matrix of our times.

The diagnosis is multilayered and complex, and Ribeiro at times only scratches the surface of what may be at stake here as he openly admits himself. At the core of his proposal is a shift in attention away from classical questions of epistemological rank, which in archaeology have tended to orbit the contentious issue of the reality of types (see also 2). Instead of foregrounding the question of type-realities – whether types, once identified, can be meaningfully said to exist and to represent something significant in the world – archaeologists are urged to recognize that typo-praxis is culturally saturated in at least two profound ways. First, devising and mobilizing types and typologies is a cultural practice itself – it may indeed have long been a foundational ‘cultural technique’ (Kulturtechnik) (3) of archaeology as a disciplined community-venture of methodical knowledge production. Typo-centric understandings of the archaeological record are quite akin to definition-centric apprehensions of the same as in both cases order, discreteness, and one-to-one correspondence are considered overriding epistemic virtues and credible pointers to a subject-independent “reality”. As such, these practices have a location of their own and they may thus notably conflict with the particularities of alternate and ever-mutating phenomenal realities and historical conditions. Discreteness may for instance lose its paradigmatic status as a descriptor of worldly order, and this is precisely what Ribeiro argues to have happened in the wake of postmodern transformations, influentially said to have deeply reconfigured the relation between the local and the global, at times even superseding such distinctions altogether. When coupled to questions of reality, types, in a similar fashion as definitions, quickly become vehicles to affirm epistemic power and knowledge authority and so help certify certain kinds of realities while supressing others. This is the paradox of modernity: to insist on monolithic understandings of the world while professing radical difference.

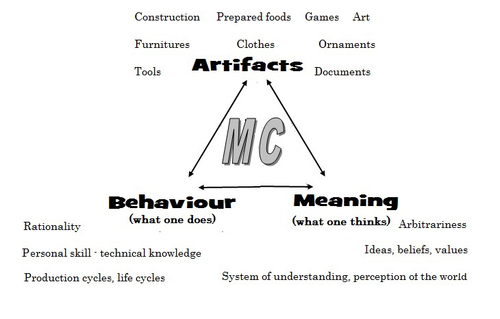

Second, and for Ribeiro more importantly, typo-praxis is not just subject to cultural variation and thus by implication is plural, it also always has its proper associated cultural milieu in which it exerts some sort of efficacy, i.e. enables action and insight. Ribeiro maintains that this sort of efficacy has become contentious under postmodern conditions and this is because culture, under the gaze of global consumerism, has lost much of its classical significance, and as “hyperculture” (4) developed new logics, significations, and material culture correspondences, essentially “flattening” the highly textured and differentiated world of modernity (p. 6). Some of these new configurations sharply violate the expectations of traditional views of culture. The postmodern situation has in this way effectively emerged as a resistant force proffering much caution and growing scepticism among archaeologists and other academics alike as received ideas about “types” and “cultures” do not seem to work anymore the same way as before. The credibility of different modes of typo-praxis, archaeological or not, in other words, may depend much more on the cultural ecology of lived experience and contemporary diagnosis than is often realized. With Ribeiro, we may say that culture concepts and type concepts are indeed co-constitutive, and what sort of types and typologies archaeologists can persuasively deploy thus also depends greatly on how we construct the link between culture and type, and how (well) we grapple with our own realities and the lessons we draw from them – yet another important reminder of how our own subjectivities figure in such foundational debates (see esp. 5).

The crisis of typo-praxis in archaeology, then, is intricately linked to the crisis of modernity, broached by Ribeiro with the labels of postmodernity and late capitalism. Upon reflection, this is not surprising at all since Tylor’s (6) influential definition of culture for example, which is extensively referenced in the paper, was both reflective of and conducive to the project of modernity and its distinctive historical formations such as empire and colonialism. Ribeiro reminds us that questions of justification and credibility, be it in the domain of type-thinking or other epistemic contexts, can never be fully divorced from the contemporary situation, and archaeologists thus need to be vigilant observers of the present, too. Typo-praxis ultimately is motivated by and draws authority from what Foucault (7) has called épistémè, the totality of pertinent parameters forming the historical a priori of understanding or the guiding unconsciousness of subjectivity within a given epoch. The crisis of archaeological typo-praxis, in this view, signifies a calling into question of the historical a priori on which much traditional type-work in archaeology was premised. Archaeologists still have to come to terms with the implications and consequences of this assessment. “Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times” offers a first poignant analysis of some of these challenges of postmodern archaeological type-thinking.

Bibliography

1. Ribeiro, A. (2024). Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times. Zenodo, 10567441, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10567441

2. Hussain, S. T. (2024). The Loss of Typological Innocence: An Archaeology of Archaeological Typo-Praxis. Zenodo, 10567441. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10547264

3. Macho, T. (2013). Second-Order Animals: Cultural Techniques of Identity and Identification. Theory, Culture & Society 30, 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413499189

4. Han, B.-C. (2022). Hyperculture: culture and globalization (Polity Press).

5. Frank, A., Gleiser, M. and Thompson, E. (2024). The blind spot: why science cannot ignore human experience (The MIT Press). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13711.001.0001

6. E. B. Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom (J. Murray).

7. Foucault, M. (2007). The order of things: an archaeology of the human sciences, Repr (Routledge).

A return to function as the basis of lithic classification

Using insights from psychology and primatology to reconsider function in lithic typologies

Recommended by Sébastien Plutniak, Felix Riede and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Vincent Delvigne and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper “A return to function as the basis of lithic classification” by Radu Iovita (2024) is a contribution to an upcoming volume on the role of typology and type-thinking in current archaeological theory and praxis edited by the PCI recommenders. In this context, the paper offers an in-depth discussion of several crucial dimensions of typological thinking in past and current lithic studies, namely:

- “common sense” in archaeology, discussed based on earlier proposals by influential anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1975),

- “function”, argued by the author to be the “fundamental property of tools”,

- “cognitive” aspects, said to be reflected in the “property we naturally use to classify” stone tools and then argued to be grounded in function,

- “traceology” as an archaeological bundle of methods and practices to determine (tool) function, discussing the current status of this research perspective in archaeology and its future.

Discussing and importantly re-articulating these concepts, Iovita ultimately aims at “establishing unified guiding principles for studying a technology that spans several million years and several different species whose brain capacities range from ca. 300–1400 cm³”.

The notion that tool function should dictate classification is not new (e.g. Gebauer 1987). It is particularly noteworthy, however, that the paper engages carefully with various relevant contributions on the topic from non-Anglophone research traditions. First, its considering works on lithic typologies published in other languages, such as Russian (Sergei Semenov), French (Georges Laplace), and German (Joachim Hahn). Second, it takes up the ideas of two French techno-anthropologists, in particular:

- Anthropologist of technics François Sigaut's (1940-2012) distinction of form, function, and “fonctionnement” (Sigaut 1991). Iovita proposes to draw and recast this tripartition, splitting the notion of function into “structural function” (a concept encompassing biological function as well as the “interface between the tool and its environment”), “operation” (which “relates to learning the function of artifacts from others and representing them through their motor associations”), and "designer-intended function” (DIF). Iovita shows how these distinctions can be used to clarify the ways and the grounds on which we build lithic typologies.

- Structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss' (1908-2009) concept of “bricolage”, influentially proposed and developed in his La pensée sauvage (Lévi-Strauss 1962); this concept was also much discussed by North American anthropologist Clifford Geertz and more recently critically re-considered in the English-speaking literature thanks to a new translation of Lévi-Strauss' original text (Lévi-Strauss 2021).

Interestingly, Iovita grounds his argumentation on insights from primatology, psychology and the cognitive sciences, to the extent that they fuel discussion on archaeological concepts and methods. Results regarding the so-called “design stance” for example play a crucial role: coined by philosopher and cognitive scientist and philosopher Daniel Dennett (1942-2024), this notion encompasses the possible discrepancies between the designer’s intended purpose and the object's current functions. DIF, as discussed by Iovita, directly relates to this idea, illustrating how concepts from other sciences can fruitfully be injected into archaeological thinking.

Lastly, readers should note the intellectual contents generated on PCI as part of the reviewing process of the paper itself: both the reviewers and the author have engaged in in-depth discussions on the idea of (tool) “function” and its contested relationship with form or typology, delineating and mapping different views on these key issues in lithic study which are worth reading on their own.

References

Gebauer, A. B. (1987). Stylistic Analysis. A Critical Review of Concepts, Models, and Interpretations, Journal of Danish Archaeology, 6, p. 223–229.

Geertz, C. (1975). Common Sense as a Cultural System, The Antioch Review, 33 (1), p. 5–26.

Iovita, R. (2024). A return to function as the basis of lithic classification. Zenodo, 7734147, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7734147

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1962). La pensée sauvage. Paris: Plon.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (2021). Wild Thought: A New Translation of “La Pensée sauvage”. Translated by Jeffrey Mehlman & John Leavitt. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l'analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d'études technologiques en préhistoire : Bilan et perspectives, Juan-les-Pins: Éditions de l'association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques, p. 21-34.

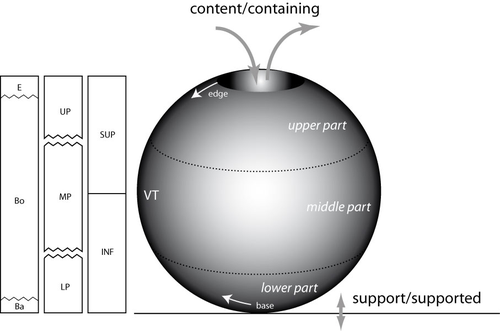

What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery.

Abstract and Concrete – Querying the Metaphysics and Geometry of Pottery Classification

Recommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers“What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery” by P. Boissinot (1) is a timely contribution to broader theoretical reflections on classification and ordering practices in archaeology, including type-construction and justification. Boissinot rightly reminds us that engagement with the type concept always touches upon the uneasy relationship between the abstract and the concrete, alternatively cast as the ongoing struggle in knowledge production between idealization and particularization. Types are always abstract and as such both ‘more’ and ‘less’ than the concrete objects they refer to. They are ‘more’ because they establish a higher-order identity of variously heterogeneous, concrete objects and they are ‘less’ because they necessarily reduce the richness of the concrete and often erase it altogether. The confusion that types evoke in archaeology and elsewhere has therefore a lot to do with the fact that types are simply not spatiotemporally distinct particulars. As abstract entities, types so almost automatically re-introduce the question of universalism but they do not decide this question, and Boissinot also tentatively rejects such ambitions. In fact, with Boissinot (1) it may be said that universality is often precisely confused with idealization, which is indispensable to all archaeological ordering practices.

Idealization, increasingly recognized as an important epistemic operation in science (2, 3), paradoxically revolves around the deliberate misrepresentation of the empirical systems being studied, with models being the paradigm cases (4). Models can go so far as to assume something strictly false about the phenomena under consideration in order to advance their epistemic goals. In the words of Angela Potochnik (5), ‘the role of idealization in securing understanding distances understanding from truth but […] this understanding nonetheless gives rise to scientific knowledge’. The affinity especially to models may in part explain why types are so controversial and are often outright rejected as ‘real’ or ‘useful’ by those who only recognize the existence of concrete particulars (nominalism). As confederates of the abstract, types thus join the ranks of mathematics and geometry, which the author identifies as prototypical abstract systems. Definitions are also abstract. According to Boissinot (1), they delineate a ‘position of limits’, and the precision and rigorousness they bring comes at the cost of subjectivity. This unites definitions and types, as both can be precise and clear-cut but they can never be strictly singular or without alternative – in order to do so, they must rely on yet another higher-order system of external standards, and so ad infinitum.

Boissinot (1) advocates a mathematical and thus by definition abstract approach to archaeological type-thinking in the realm of pottery, as the abstractness of this approach affords relatively rigorous description based on the rules of geometry. Importantly, this choice is not a mysterious a priori rooted in questionable ideas about the supposed superiority of such an approach but rather is the consequence of a careful theoretical exploration of the particularities (domain-specificities) of pottery as a category of human practice and materiality. The abstract thus meets the concrete again: objects of pottery, in sharp contrast to stone artefacts for example, are the product of additive processes. These processes, moreover, depend on the ‘fusion’ of plastic materials and the subsequent fixation of the resulting configuration through firing (processes which, strictly speaking, remove material, such as stretching, appear to be secondary vis-à-vis global shape properties). Because of this overriding ‘fusion’ of pottery, the identification of parts, functional or otherwise, is always problematic and indeterminate to some extent. As products of fusion, parts and wholes represent an integrated unity, and this distinguishes pottery from other technologies, especially machines. The consequence is that the presence or absence of parts and their measurements may not be a privileged locus of type-construction as they are in some biological contexts for example. The identity of pottery objects is then generally bound to their fusion. As a ‘plastic montage’ rather than an assembly of parts, individual parts cannot simply be replaced without threatening the identity of the whole. Although pottery can and must sometimes be repaired, this renders its objects broadly morpho-static (‘restricted plasticity’) rather than morpho-dynamic, which is a condition proper to other material objects such as lithic (use and reworking) and metal artefacts (deformation) but plays out in different ways there. This has a number of important implications, namely that general shape and form properties may be expected to hold much more relevant information than in technological contexts characterized by basal modularity or morpho-dynamics.

It is no coincidence that ‘fusion’ is also emphasized by Stephen C. Pepper (6) as a key category of what he calls contextualism. Fusion for Pepper pays dividends to the interpenetration of different parts and relations, and points to a quality of wholes which cannot be reduced any further and integrates the details into a ‘more’. Pepper maintains that ‘fusion, in other words, is an agency of simplification and organization’ – it is the ‘ultimate cosmic determinator of a unit’ (p. 243-244, emphasis added). This provides metaphysical reasons to look at pottery from a whole-centric perspective and to foreground the agency of its materiality. This is precisely what Boissinot (1) does when he, inspired by the great techno-anthropologist François Sigaut (7), gestures towards the fact that elementarily a pot is ‘useful for containing’. He thereby draws attention not to the function of pottery objects but to what pottery as material objects do by means of their material agency: they disclose a purposive tension between content and container, the carrier and carried as well as inclusion and exclusion, which can also be understood as material ‘forces’ exerted upon whatever is to be contained. This, and not an emic reading of past pottery use, leads to basic qualitative distinctions between open and closed vessels following Anna O. Shepard’s (8) three basic pottery categories: unrestricted, restricted, and necked openings. These distinctions are not merely intuitive but attest to the object-specificity of pottery as fused matter.

This fused dimension of pottery also leads to a recognition that shapes have geometric properties that emerge from the forced fusion of the plastic material worked, and Boissinot (1) suggests that curvature is the most prominent of such features, which can therefore be used to describe ‘pure’ pottery forms and compare abstract within-pottery differences. A careful mathematical theorization of curvature in the context of pottery technology, following George D. Birkhoff (9), in this way allows to formally distinguish four types of ‘geometric curves’ whose configuration may serve as a basis for archaeological object grouping. The idealization involved in this proposal is not accidental but deliberately instrumental – it reminds us that type-thinking in archaeology cannot escape the abstract. It is notable here that the author does not suggest to simply subject total pottery form to some sort of geometric-morphometric analysis but develops a proposal that foregrounds a limited range of whole-based geometric properties (in contrast to part-based) anchored in general considerations as to the material specificity of pottery as quasi-species of objects.

As Boissinot (1) notes himself, this amounts to a ‘naturalization’ of archaeological artefacts and offers somewhat of an alternative (a third way) to the old discussion between disinterested form analysis and functional (and thus often theory-dependent) artefact groupings. He thereby effectively rejects both of these classic positions because the first ignores the particularities of pottery and the real function of artefacts is in most cases archaeologically inaccessible. In this way, some clear distance is established to both ethnoarchaeology and thing studies as a project. Attending to the ‘discipline of things’ proposal by Bjørnar Olsen and others (10, 11), and by drawing on his earlier work (12), Boissinot interestingly notes that archaeology – never dealing with ‘complete societies’ – could only be ‘deficient’. This has mainly to do with the underdetermination of object function by the archaeological record (and the confusion between function and functionality) as outlined by the author. It seems crucial in this context that Boissinot does not simply query ‘What is a thing?’ as other thing-theorists have previously done, but emphatically turns this question into ‘In what way is it not the same as something else?’. He here of course comes close to Olsen’s In Defense of Things insofar as the ‘mode of being’ or the ‘ontology’ of things is centred. What appears different, however, is the emphasis on plurality and within-thing heterogeneity on the level of abstract wholes. With Boissinot, we always have to speak of ontologies and modes of being and those are linked to different kinds of things and their material specificities. Theorizing and idealizing these specificities are considered central tasks and goals of archaeological classification and typology. As such, this position provides an interesting alternative to computational big-data (the-more-the-better) approaches to form and functionally grounded type-thinking, yet it clearly takes side in the debate between empirical and theoretical type-construction as essential object-specific properties in the sense of Boissinot (1) cannot be deduced in a purely data-driven fashion.

Boissinot’s proposal to re-think archaeological types from the perspective of different species of archaeological objects and their abstract material specificities is thought-provoking and we cannot stop wondering what fruits such interrogations would bear in relation to other kinds of objects such as lithics, metal artefacts, glass, and so forth. In addition, such meta-groupings are inherently problematic themselves, and they thus re-introduce old challenges as to how to separate the relevant super-wholes, technological genesis being an often-invoked candidate discriminator. The latter may suggest that we cannot but ultimately circle back on the human context of archaeological objects, even if we, for both theoretical and epistemological reasons, wish to embark on strictly object-oriented archaeologies in order to emancipate ourselves from the ‘contamination’ of language and in-built assumptions.

Bibliography

1. Boissinot, P. (2024). What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery, Zenodo, 7429330, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433

2. Fletcher, S.C., Palacios, P., Ruetsche, L., Shech, E. (2019). Infinite idealizations in science: an introduction. Synthese 196, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02069-6

3. Potochnik, A. (2017). Idealization and the aims of science (University of Chicago Press). https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226507194.001.0001

4. J. Winkelmann, J. (2023). On Idealizations and Models in Science Education. Sci & Educ 32, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00291-2

5. Potochnik, A. (2020). Idealization and Many Aims. Philosophy of Science 87, 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1086/710622

6. Pepper S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (University of California Press).

7. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l’analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d’études Technologiques En Préhistoire. Bilan et Perspectives (Association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques), pp. 21–34.

8. Shepard, A. O. (1956). Ceramics for the Archeologist (Carnegie Institution of Washington n° 609).

9. Birkhoff G. D. (1933). Aesthetic Measure (Harvard University Press).

10. Olsen, B. (2010). In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects (AltaMira Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/ept014

11. Olsen, B., Shanks, M., Webmoor, T., Witmore, C. (2012). Archaeology: the discipline of things (University of California Press). https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520954007

12. Boissinot, P. (2011). “Comment sommes-nous déficients ?” in L’archéologie Comme Discipline ? (Le Seuil), pp. 265–308.

Comparing summed probability distributions of shoreline and radiocarbon dates from the Mesolithic Skagerrak coast of Norway

Taking the Reverend Bayes to the seaside: Improving Norwegian Mesolithic shoreline dating with advanced statistical approaches

Recommended by Felix Riede based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper entitled “Comparing summed probability distributions of shoreline and radiocarbon dates from the Mesolithic Skagerrak coast of Norway” by Isak Roalkvam and Steinar Solheim (2024) sheds new light on the degree to which shoreline dating may be used as a reliable chronological and palaeodemographic proxy in the Mesolthic of southern Norway.

Based on geologically motivated investigations of eustatic and isostatic sea-level changes, shoreline dating has long been used as a method to date archaeological sites in Scandinavia, not least in Norway (e.g., Bjerck 2008; Astrup 2018). Establishing reliable sea-level curves requires much effort and variations across regions may be substantial. While this topic has seen a great deal of attention in Norway specifically, many purely geological questions remain. In addition, dating archaeological sites by linking their elevation to previously established seal-level curves relies strongly on the foundational assumption that such sites were in fact shore-bound. Given the strong contrast between terrestrial and marine productivity in high-latitude regions such as Norway, this assumption per se is not unreasonable. It is very likely that the sea has played a decisive role in the lives of Stone Age peoples throughout (Persson et al. 2017), just as it has in later periods here. However, many confounding factors relating to both taphonomy and human behaviour are also likely to have loosened the shore/site relationship. Systematic variations driven by cultural norms about settlement location, mobility, as well as factors such as shelter construction, fuel use and a range of other possible factors could variously have impacted the validity or at least the precision of shoreline dating.

By developing a new methodology for handling and assessing a large number of shoreline dated sites, Roalkvam and Solheim use state-of-the-art Bayesian statistical methods to compare shoreline and radiocarbon dates as proxies for population activity. The probabilistic treatment of shoreline dates in this way is novel, and the divergences between the two data sets are interpreted by the authors in light of specific behavioural, cultural, and demographic changes. Many of the peaks and troughs observed in these time-series may be interpreted in light of long-observed cultural transitions while others may relate to population dynamics now also visible in palaeogenomic analyses (Günther et al. 2018; Manninen et al. 2021). Overall, this paper makes an innovative and fresh contribution to the use of shoreline dating in Norwegian archaeology, specifically by articulating it with recent developments in Open Science and data-driven approaches to archaeological questions (Marwick et al. 2017).

References

Astrup, P. M. 2018. Sea-Level Change in Mesolithic Southern Scandinavia : Long- and Short-Term Effects on Society and the Environment. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Bjerck, H. B. 2008. Norwegian Mesolithic Trends: A Review. In Mesolithic Europe, edited by Geoff Bailey and Penny Spikins, 60–106. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Günther, T., Malmström, H., Svensson, E. M., Omrak, A., Sánchez-Quinto, F., Kılınç, G. M., Krzewińska, M. et al. 2018. Population Genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating Early Postglacial Migration Routes and High-Latitude Adaptation. PLOS Biology 16 (1): e2003703. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703

Manninen, M. A., Damlien, H., Kleppe, J. I., Knutsson, K., Murashkin, A., Niemi, A. R., Rosenvinge, C. S. and Persson, P. 2021. First Encounters in the North: Cultural Diversity and Gene Flow in Early Mesolithic Scandinavia. Antiquity 95 (380): 310–28. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.252

Marwick, B., d’Alpoim Guedes, J. A., Barton, C. M., Bates, L. A., Baxter, M., Bevan, A., Bollwerk, E. A. et al. 2017. Open Science in Archaeology. The SAA Archaeological Record 17 (4): 8–14. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/72n8g

Persson, P., Riede, F., Skar, B., Breivik, H. M. and Jonsson, L. 2017. The Ecology of Early Settlement in Northern Europe: Conditions for Subsistence and Survival. Sheffield: Equinox.

Roalkvam, I. and Solheim, S. (2024). Comparing summed probability distributions of shoreline and radiocarbon dates from the Mesolithic Skagerrak coast of Norway, SocArXiv, 2f8ph, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/2f8ph

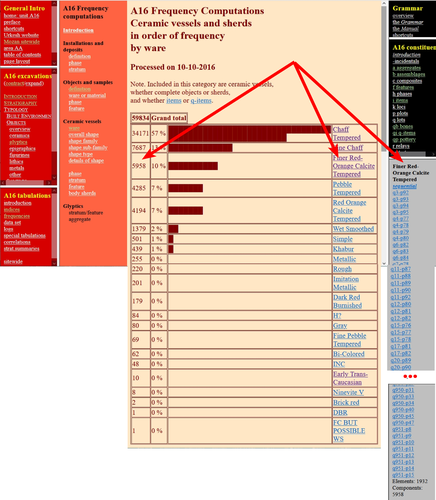

The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A Website Approach to Archaeological Typology.

Roster and Lexicon – A Radical Digital-Dialogical Approach to Questions of Typology and Categorization in Archaeology

Recommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and 2 anonymous reviewers“The density of types and the dignity of the fragment. A website approach to archaeological typology” by G. Buccellati and M. Kelly-Buccellati (1) is a contribution to the rapidly growing literature on digital approaches to archaeological data management, expertly showcasing the significant theoretical and epistemological impetus of such work. The authors offer a conceptually lucid discussion of key concepts in archaeological ordering practices surrounding the longstanding tension between so-called ‘etic’ and ‘emic’ approaches, thereby providing a thorough systematic of how to think through sameness and difference in the context of voluminous digital archaeological data.

As a point of departure, the authors reconsider the relationship between archaeological fragments – spatiotemporally bounded artefacts and features – and their larger meaning-giving totality as the primary locus of archaeological knowledge. Typology can then be said to serve this overriding quest to resolve the conflict between parts and wholes, as the parts themselves are never sufficient to render the whole but the whole remains elusive without reference to the parts. Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati here make an interesting point about the importance to register the globality of the archaeological record – that is, literally everything encountered in the soil – without making any prior choices as to what supposedly matters and what not. The distinctiveness of the archaeological enterprise, according to them, indeed consists of the circumstance that merely disconnected fragments come to the attention of archaeologists and the only objective data that can be attained, because of this, are about the situated location of fragments in the ground and their relation to other fragments – what they call ‘emplacement’. This, we would add, includes the relationship of fragments with human observers and the employed methods of excavation as observation. As the authors say: “[i]t is in this sense that the fragments are natively digital: they are atoms that do not cohere into a typological whole”.

The systematic exploration of how the so recovered fragments may be re-articulated is then essentially the goal of archaeological categorization and typology but these practices can only ever be successful if the whole context of original ‘emplacement’ is carefully taken into consideration. This reconstruction of the fundamental epistemological situation archaeology finds itself in leads the authors to a general rejection of ‘more’ vs. ‘less’ objective or even subjective ordering practices as such qualifications tend to miss the point. What matters is to enable the flexible and scalable confrontation of isolated archaeological fragments, to do experiment with and test different part-whole relations and their possible knowledge contributions. It is no coincidence that the authors insist on a dynamical approach to ordering practices and type-thinking in archaeology here, which in many ways comes often very close to the general conceptual orientation philosopher Stephen C. Pepper (2) has called ‘organicism’ – a preoccupation of resolving the tension between heterogeneous fragments and coherent wholes without losing sight of the specificity of each single fragment. In the view of organicist thinkers, and the authors seem to share this recognition, to take complexity seriously means to centre the dialectics between fragments and wholes in their entirety. This notion is directly reflected in the authors’ interesting definition of ‘big data’ in archaeology as a multi-layered and multi-referential system of organizing the totality of observations of emplacement (the Global record).

Based on this broader exposition, Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati make some perceptive and noteworthy observations vis-à-vis the aforementioned emic-etic distinction that has caused so much archaeological confusion and debate (3–6). To begin with, emic and etic designate different systemic logics of organizing observable sameness and difference. Emic systems are closed and foreground the idea of the roster, they recognize only a limited set of types whose identity depends on relative differences. Etic systems, on the other hand, are in principle open (and even open-ended) and rely on the notion of the lexicon; they enlist a principally endless repertoire of traits, types and sub-types (classes and sub-classes may be added to this list of course). Difference in etic systems is moreover defined according to some general standards that appear to eclipse the standards of the system itself. Etic systems therefore tend to advocate supposedly universal principles of how to establish similarity vs. difference, although, in reality, there is substantial debate as to what these principles may be or whether such endeavour is a useful undertaking. In the wild, both etic and emic systems of ordering and categorization are of course encountered in the plural but etic systems deploy external standards of order while emic systems operate via internal standards. An interesting observation by the authors in this context is that archaeological reasoning in relation to sameness and difference is almost never either exclusively etic or exclusively emic. The simple reason is that any grouping of fragments according to technological (means/modes of production) or functional considerations (use-wear, tool design, relation between form and function) based on empirical evidence is typically already infused by emic standards. The classic example from the analysis of archaeological pottery is ware groups, which reference the nexus of technological know-how and concrete practices, and which rely, in a given context, on internal, relative differentiations between the respective observed practices. Yet ignoring these distinctions would sideline significant knowledge on the past.

These discussions are refreshing as they may indicate that ordering practices – when considered as an end in themselves – misconstrue the archaeological process as static and so advocate for categories, classes, and types to be carved out before any serious analysis can begin. It could in fact be argued that in doing so, they merely construct a new closed system, then emic by definition. Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati propose an alternative without discarding the intuition that ordering archaeological materials is conditional to the inferential and knowledge-production process: they propose that typologies should be treated as arguments. Moreover, the sort of argument they have in mind is to a lesser extent ‘formal-logical’ but instead emphatically ‘dialogical’ in nature, as such argumentative form helps to combat the inherent static-ness of ordering practices the authors criticize, and so discloses a radically dynamic approach to the undertaking of fragment-whole matching. The organicist inclination to preserve ‘the dignity of fragments’ while working towards their resolution in attendant wholes and sub-wholes further gives rise to the idea that such ‘native digital fragments’ must be brought into systematic conversation with one another, acknowledging the involved complexity. To this end, the authors frame ordering work and typo-praxis as a ‘digital discourse’ and ask what the conditions and possibilities for such discourse are and how it can be facilitated. It is here that they put forward the idea that the webpage may provide an ideal epistemic model system to promote the preservation of emplaced archaeological fragments while simultaneously promoting multistranded and multi-context explorations of fragment coherence and articulation. The website enables unique forms of exploration and engagement with data and new arguments escaping the fixity of the analogue-printed which dominates current archaeological practice. Similar experiences were for example made in the context of Gardin’s ‘logicism’, leading to broadly comparable attempts to overcome the analogue with more dynamic, HTML/web-based forms of data presentation, exploration and discussion (7, 8).

As such, Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati table a range of fresh arguments for re-thinking typology beyond and with text at the same time, to enable ‘dynamic reading’ of fragment-whole relationships in an increasingly digital world. Their proposal comes thereby close to what has been termed ‘deep mapping’ in the context of critical cartographies and other spatially-inclined scholarship in the Anglophone world (9, 10). Deep maps seek to transcend the epistemological limitations of 2D-representations of spatiality on traditional maps and introduce different layers of informational depth and heterogeneity, which, similarly to the living digital webpage proposed by the authors, can be continuously extended and revised and which may also greatly promote multidisciplinary and team-based research endeavours. In the same spirit as the authors’ ‘digital discourse’, deep mapping draws attention to the knowledge potential of bringing together the heterogeneous, the etic and the emic, and to pay more attention to ‘multiplanar’ and ‘multilinear’ relationships as well as the associated relations of relations. This proposal to deploy types and typology in general as dynamic arguments is linked to the ambition to contribute to and work on the narrativization of the archaeological record without tacit (and often unconscious) conceptual pre-subscription, countering typologies that remain largely in the abstract and so have contributed to the creeping anonymity of the past.

Bibliography

1. Buccellati, G. and Kelly-Buccellati, M. (2023). The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A website approach to archaeological typology, Zenodo, 7743834, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7743834.

2. Pepper, S C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (Univ. of California Press).

3. Hayden, B. (1984). Are Emic Types Relevant to Archaeology? Ethnohistory 31, 79–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/482057

4. Tostevin, G. B. (2011). An Introduction to the Special Issue: Reduction Sequence, Chaîne Opératoire, and Other Methods: The Epistemologies of Different Approaches to Lithic Analysis. PaleoAnthropology, 293−296. https://www.doi.org/10.4207/PA.2011.ART59

5. Tostevin, G. B. (2013). Seeing lithics: a middle-range theory for testing for cultural transmission in the pleistocene (Oakville, CT: Oxbow Books).

6. Boissinot, P. (2015). Qu’est-ce qu’un fait archéologique? (Éditions EHESS). https://doi.org/10.4000/lectures.19921

7. Gardin, J.-C. and Roux, V. (2004). The Arkeotek Project: a European Network of Knowledge Bases in the Archaeology of Techniques. Archeologia e Calcolatori 15, 25–40.

8. Husi, P. (2022). La céramique médiévale et moderne du bassin de la Loire moyenne, chrono-typologie et transformation des aires culturelles dans la longue durée (6e—17e s.) (FERACF).

9. Bodenhamer, D. J., Corrigan, J. and Harris, T. M. (2015). Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives (Indiana University Press).

10. Gillings, M., Hacigüzeller, P. and Lock, G. R. (2019). Re-mapping archaeology: critical perspectives, alternative mappings (Routledge).

Research perspectives and their influence for typologies

Complexity and Purpose – A Pragmatic Approach to the Diversity of Archaeological Classificatory Practice and Typology

Recommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Ulrich Veit, Martin Hinz, Artur Ribeiro and 1 anonymous reviewer“Research perspectives and their influence for typologies” by E. Giannichedda (1) is a contribution to the upcoming volume on the role of typology and type-thinking in current archaeological theory and praxis edited by the recommenders. Taking a decidedly Italian perspective on classificatory practice grounded in what the author dubs the “history of material culture”, Giannichedda offers an inventory of six divergent but overall complementary modes of ordering archaeological material: i) chrono-typological and culture-historical, ii) techno-anthropological, iii) social, iv) socio-economic and v) cognitive. These various lenses broadly align with similarly labeled perspectives on the archaeological record more generally. According to the author, they lend themselves to different ways of identifying and using types in archaeological work. Importantly, Giannichedda reminds us that no ordering practice is a neutral act and typologies should not be devised for their own sake but because we have specific epistemic interests. Even though this view is certainly not shared by everyone involved in the broader debate on the purpose and goal of systematics, classification, typology or archaeological taxonomy (2–4), the paper emphatically defends the long-standing idea that ordering practices are not suitable to elucidate the structure and composition of reality but instead devise tools to answer certain questions or help investigate certain dimensions of complex past realities. This position considers typologies as conceptual prosthetics of knowing, a view that broadly resonates with what is referred to as epistemic instrumentalism in the philosophy of science (5, 6). Types and type-work should accordingly reflect well-defined means-end relationships.

Based on the recognition of archaeology as part of an integrated “history of material culture” rooted in a blend of continental and Anglophone theories, Giannichedda argues that type-work should pay attention to relevant relations between various artefacts in a given historical context that help further historical understanding. Classificatory practice in archaeology – the ordering of artefactual materials according to properties – must thus proceed with the goal of multifaceted “historical reconstruction in mind”. It should serve this reconstruction, and not the other way around. By drawing on the example of a Medieval nunnery in the Piedmont region of northwestern Italy, Giannichedda explores how different goals of classification and typo-praxis (linked to i-v; see above) foreground different aspects, features, and relations of archaeological materials and as such allow to pinpoint and examine different constellations of archaeological objects. He argues that archaeological typo-praxis, for this reason, should almost never concern itself with isolated artefacts but should take into account broader historical assemblages of artefacts. This does not necessarily mean to pay equal attention to all available artefacts and materials, however. To the contrary, in many cases, it is necessary to recognize that some artefacts and some features are more important than others as anchors grouping materials and establishing relations with other objects. An example are so-called ‘barometer objects’ (7) or unique pieces which often have exceptional informational value but can easily be overlooked when only shared features are taken into consideration. As Giannichedda reminds us, considering all objects and properties equally is also a normative decision and does not render ordering less subjective. The archaeological analysis of types should therefore always be complemented by an examination of variants, even if some of these variants are idiosyncratic or even unique. A type, then, may be difficult to define universally.

In total, “Research perspectives and their influence for typologies” emphasizes the need for “elastic” and “flexible” approaches to archaeological types and typologies in order to effectively respond to the manifold research interests cultivated by archaeologists as well as the many and complex past realities they face. Complexity is taken here to indicate that no single research perspective and associated mode of ordering can adequately capture the dimensionality and richness of these past realities and we can therefore only benefit from multiple co-existing ways of grouping and relating archaeological artefacts. Different logics of grouping may simply reveal different aspects of these realities. As such, Giannichedda’s proposal can be read as a formulation of the now classic pluralism thesis (8–11) – that only a plurality of ways of ordering and interrelating artefacts can unlock the full suite of relationships within historical assemblages archaeologists are interested in.

Bibliography

1. Giannichedda, E. (2023). Research perspectives and their influence for typologies, Zenodo, 7322855, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7322855

2. Dunnell, R. C. (2002). Systematics in Prehistory, Illustrated Edition (The Blackburn Press, 2002).

3. Reynolds, N. and Riede, F. (2019). House of cards: cultural taxonomy and the study of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Antiquity 93, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.49

4. Lyman, R. L. (2021). On the Importance of Systematics to Archaeological Research: the Covariation of Typological Diversity and Morphological Disparity. J Paleo Arch 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00077-6

5. Van Fraassen, B. C. (2002). The empirical stance (Yale University Press).

6. Stanford, P. K. (2006). Exceeding Our Grasp: Science, History, and the Problem of Unconceived Alternatives (Oxford University Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/0195174089.001.0001

7. Radohs, L. (2023). Urban elite culture: a methodological study of aristocracy and civic elites in sea-trading towns of the southwestern Baltic (12th-14th c.) (Böhlau).

8. Kellert, S. H., Longino, H. E. and Waters, C. K. (2006). Scientific pluralism (University of Minnesota Press).

9. Cat, J. (2012). Essay Review: Scientific Pluralism. Philosophy of Science 79, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/664747

10. Chang, H. (2012). Is Water H2O?: Evidence, Realism and Pluralism (Springer Netherlands). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3932-1

11. Wylie, A. (2015). “A plurality of pluralisms: Collaborative practice in archaeology” in Objectivity in Science, (Springer), pp. 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14349-1_10

From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions

Revitalising archaeological corpus publications through digitisation – the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae as exemplary cases

Recommended by Felix Riede, Sébastien Plutniak and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla SobotkovaThe paper entitled “From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions” submitted by Frederic Auth and colleagues discusses how those rich and often meticulously illustrated catalogues of particular find classes that exist in many corners of archaeology can be brought to the cutting edge of contemporary research through digitisation. This paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology, taxonomy, classification theory, and computational approaches in archaeology.

Auth et al. (2023) begin with outlining the useful notion of the ‘thing-edition’ originally coined by Kerstin Hofmann in the context of her work with the many massive corpora of finds that have characterised, in particular, earlier archaeological knowledge production in Germany (Hofmann et al. 2019; Hofmann 2018). This work critically examines changing trends in the typological characterisation and recording of various find categories, their theoretical foundations or lack thereof and their legacy on contemporary practice. The present contribution focuses on what happens with such corpora when they are integrated into digitisation projects, specifically the efforts by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), the so-called iDAI.world and in regard to two Roman-era material culture groups, the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum (Roman finds from beyond the empire’s borders in eight printed volumes covering thousands of finds of various categories), and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae (Roman plain ware).

Drawing on Bruno Latour’s (2005) actor-network theory (ANT), Auth et al. discuss and reflect on the challenges met and choices to be made when thing-editions are to be transformed into readily accessible data, that is as linked to open, usable data. The intellectual and infrastructural workload involved in such digitisation projects is not to be underestimated. Here, the contribution by Auth et al. excels in the manner that it does not present the finished product – the fully digitised corpora – but instead offers a glimpse ‘under the hood’ of the digitisation process as an interaction between analogue corpus, research team, and the technologies at hand. These aspects were rarely addressed in the literature, rooted in the 1970s early work (Borillo and Gardin 1974; Gaines 1981), on archaeological computerised databases, focused on technical dimensions (see Rösler 2016 for an exception). Their paper can so also be read in the broader context of heterogeneous computer-assisted knowledge ecologies and ‘mangles of practice’ (see Pickering and Guzik 2009) in which practitioners and technological structures respond to each other’s needs and attempt to cooperate in creative ways. As such, Auth et al.’s considerations not least offer valuable resources for Science and Technology Studies-inspired discussions on the cross-fertilization of archaeological theory, practice and currently emerging material and virtual research infrastructures and can be read in conjunction to Gavin Lucas’ (2022) paper on ‘machine epistemology’ due to appear in the same volume.

Perhaps more importantly, however, the work by Auth and colleagues (2023) exemplifies the due diligence required in not merely turning a catalogue from paper to digital document but in transforming such catalogues into long-lasting and patently usable repositories of generations of scholars to come. Deploying the Latourian notions of trade-off and recursive reference, Auth et al. first examine the structure, strengths, and weakness of the two corpora before moving on to showing how the freshly digitised versions offer new and alternative ways of analysing the archaeological material at hand, notably through immediate visualisation opportunities, through ceramic form combinations, and relational network diagrams based on the data inherent in the respective thing-editions.

Catalogues including basic descriptions and artefact illustrations exist for most if not all archaeological periods. They constitute an essential backbone of archaeological work as repeated access to primary material is impractical if not impossible. The catalogues addressed by Auth et al. themselves reflect major efforts on behalf of archaeological experts to arrive at clear and operational classifications in a pre-computerised era. The continued and expanded efforts by Auth and colleagues build on these works and clearly demonstrate the enormous analytical potential to make such data not merely more accessible but also more flexibly interoperable. Their paper will therefore be an important reference for future work with similar ambitions facing similar challenges.

References

Auth, Frederic, Katja Rösler, Wenke Domscheit, and Kerstin P. Hofmann. 2023. “From Paper to Byte: A Workshop Report on the Digital Transformation of Two Thing Editions.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8214563

Borillo, Mario, and Jean-Claude Gardin. 1974. Les Banques de Données Archéologiques. Marseille: Éditions du CNRS.

Gaines, Sylvia W., ed. 1981. Data Bank Applications in Archaeology. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Hofmann, Kerstin P. 2018. “Dingidentitäten Und Objekttransformationen. Einige Überlegungen Zur Edition von Archäologischen Funden.” In Objektepistemologien. Zum Verhältnis von Dingen Und Wissen, edited by Markus Hilgert, Kerstin P. Hofmann, and Henrike Simon, 179–215. Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 59. Berlin: Edition Topoi. https://dx.doi.org/10.17171/3-59

Hofmann, Kerstin P., Susanne Grunwald, Franziska Lang, Ulrike Peter, Katja Rösler, Louise Rokohl, Stefan Schreiber, Karsten Tolle, and David Wigg-Wolf. 2019. “Ding-Editionen. Vom Archäologischen (Be-)Fund Übers Corpus Ins Netz.” E-Forschungsberichte des DAI 2019/2. E-Forschungsberichte Des DAI. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2236/6674

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lucas, Gavin. 2022. “Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7622162

Pickering, Andrew, and Keith Guzik, eds. 2009. The Mangle in Practice: Science, Society, and Becoming. The Mangle in Practice. Science and Cultural Theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rösler, Katja. 2016. “Mit Den Dingen Rechnen: ‚Kulturen‘-Forschung Und Ihr Geselle Computer.” In Massendinghaltung in Der Archäologie. Der Material Turn Und Die Ur- Und Frühgeschichte, edited by Kerstin P. Hofmann, Thomas Meier, Doreen Mölders, and Stefan Schreiber, 93–110. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

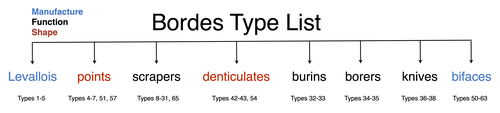

Tool types and the establishment of the Late Palaeolithic (Later Stone Age) cultural taxonomic system in the Nile Valley

Cultural taxonomic systems and the Late Palaeolithic/Later Stone Age prehistory of the Nile Valley – a critical review

Recommended by Felix Riede, Sébastien Plutniak and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Giuseppina Mutri and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper entitled “Tool types and the establishment of the Late Palaeolithic (Later Stone Age) cultural taxonomic system in the Nile Valley” submitted by A. Leplongeon offers a review of the many cultural taxonomic in use for the prehistory – especially the Late Palaeolithic/Late Stone Age – of the Nile Valley (Leplongeon 2023). This paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology and taxonomy in archaeology.

Issues of cultural taxonomy have recently risen to the forefront of archaeological debate (Reynolds and Riede 2019; Ivanovaitė et al. 2020; Lyman 2021). Archaeological systematics, most notably typology, have roots in the research history of a particular region and period (e.g. Plutniak 2022); commonly, different scholars employ different and at times incommensurable systems, often leading to a lack of clarity and inter-regional interoperability. African prehistory is not exempt from this debate (e.g. Wilkins 2020) and, in fact, such a situation is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in the iconic Nile Valley. The Nile Valley is marked by a complex colonial history and long-standing archaeological interest from a range of national and international actors. It is also a vital corridor for understanding human dispersals out of and into Africa, and along the North African coastal zone. As Leplongeon usefully reviews, early researchers have, as elsewhere, proposed a variety of archaeological cultures, the legacies of which still weigh in on contemporary discussions. In the Nile Valley, these are the Kubbaniyan (23.5-19.3 ka cal. BP), the Halfan (24-19 ka cal. BP), the Qadan (20.2-12 ka cal BP), the Afian (16.8-14 ka cal. BP) and the Isnan (16.6-13.2 ka cal. BP) but their temporal and spatial signatures remain in part poorly constrained, or their epistemic status debated. Leplongeon’s critical and timely chronicle of this debate highlights in particular the vital contributions of the many female prehistorians who have worked in the region – Angela Close (e.g. 1978; 1977) and Maxine Kleindienst (e.g. 2006) to name just a few of the more recent ones – and whose earlier work had already addressed, if not even solved many of the pressing cultural taxonomic issues that beleaguer the Late Palaeolithic/Later Stone Age record of this region.

Leplongeon and colleagues (Leplongeon et al. 2020; Mesfin et al. 2020) have contributed themselves substantially to new cultural taxonomic research in the wider region, showing how novel quantitative methods coupled with research-historical acumen can flag up and overcome the shortcomings of previous systematics. Yet, as Leplongeon also notes, the cultural taxonomic framework for the Nile Valley specifically has proven rather robust and does seem to serve its purpose as a broad chronological shorthand well. By the same token, she urges due caution when it comes to interpreting these lithic-based taxonomic units in terms of past social groups. Cultural systematics are essential for such interpretations, but age-old frameworks are often not fit for this purpose. New work by Leplongeon is likely to not only continue the long tradition of female prehistorians working in the Nile Valley but also provides an epistemologically and empirically more robust platform for understanding the social and ecological dynamics of Late Palaeolithic/Later Stone Age communities there.

Bibliography

Close, Angela E. 1977. The Identification of Style in Lithic Artefacts from North East Africa. Mémoires de l’Institut d’Égypte 61. Cairo: Geological Survey of Egypt.

Close, Angela E. 1978. “The Identification of Style in Lithic Artefacts.” World Archaeology 10 (2): 223–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1978.9979732

Ivanovaitė, Livija, Serwatka, Kamil, Steven Hoggard, Christian, Sauer, Florian and Riede, Felix. 2020. “All These Fantastic Cultures? Research History and Regionalization in the Late Palaeolithic Tanged Point Cultures of Eastern Europe.” European Journal of Archaeology 23 (2): 162–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2019.59

Kleindienst, M. R. 2006. “On Naming Things: Behavioral Changes in the Later Middle to Earlier Late Pleistocene, Viewed from the Eastern Sahara.” In Transitions Before the Transition. Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age, edited by E. Hovers and Steven L. Kuhn, 13–28. New York, NY: Springer.

Leplongeon, Alice. 2023. “Tool Types and the Establishment of the Late Palaeolithic (Later Stone Age) Cultural Taxonomic System in the Nile Valley.” https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8115202

Leplongeon, Alice, Ménard, Clément, Bonhomme, Vincent and Bortolini, Eugenio. 2020. “Backed Pieces and Their Variability in the Later Stone Age of the Horn of Africa.” African Archaeological Review 37 (3): 437–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-020-09401-x

Lyman, R. Lee. 2021. “On the Importance of Systematics to Archaeological Research: The Covariation of Typological Diversity and Morphological Disparity.” Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 4 (1): 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00077-6

Mesfin, Isis, Leplongeon, Alice, Pleurdeau, David, and Borel, Antony. 2020. “Using Morphometrics to Reappraise Old Collections: The Study Case of the Congo Basin Middle Stone Age Bifacial Industry.” Journal of Lithic Studies 7 (1): 1–38. https://doi.org/10.2218/jls.4329

Plutniak, Sébastien. 2022. “What Makes the Identity of a Scientific Method? A History of the ‘Structural and Analytical Typology’ in the Growth of Evolutionary and Digital Archaeology in Southwestern Europe (1950s–2000s).” Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 5 (1): 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-022-00119-7