Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers▲ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

29 Jan 2024

Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept researchJ.Y Blaise, I.Dudek, L.Bergerot, G.Simon https://zenodo.org/record/79831633D Models, Knowledge and Visualization: a prototype for 3D virtual models according to plausible criteriaRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Robert Bischoff and Louise TharandtThe construction of 3D realities is deeply embedded in archaeological practices. From sites to artifacts, archaeology has dedicated itself to creating digital copies for the most varied purposes. The paper “Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's 3 scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research” (Jean-Yves et al 2024) represents an advance, in the sense that it does not just deal with a three-dimensional theory for archaeological practice, but rather offers proposals regarding the epistemic component, how it is possible to represent knowledge through the workflow of 3D virtual reconstructions themselves. The authors aim to unite three main axes - knowledge modeling, visual encoding and 3D content reuse - (Jean-Yves et al 2024: 2), which, for all intents and purposes, form the basis of this article. With regard to the first aspect, this work questions how it is possible to transmit the knowledge we want to a 3D model and how we can optimize this epistemic component. A methodology based on plausibility criteria is offered, which, for the archaeological field, offers relevant space for reflection. Given our inability to fully understand the object or site that is the subject of the 3D representation, whether in space or time, building a method based on probabilistic categories is probably one of the most realistic approaches to the realities of the past. Thus, establishing a plausibility criterion allows the user to question the knowledge that is transmitted through the representation, and can corroborate or refute it in future situations. This is because the role of reusing these models is of great interest to the authors, a perfectly justifiable sentiment, as it encourages a critical view of scientific practices. Visual encoding is, in terms of its conjunction with knowledge practices, a key element. The notion of simplicity under Maeda's (2006) design principles not only represents a way of thinking that favors operability, but also a user-friendly design in the prototype that the authors have created. This is also visible when it comes to the reuse of parts of the models, in a chronological logic: adapting the models based on architectural elements that can be removed or molded is a testament to intelligent design, whereby instead of redoing models in their entirety, they are partially used for other purposes. All these factors come together in the final prototype, a web application that combines relational databases (RDBMS) with a data mapper (MassiveJS), using the PHP programming language. The example used is the Marmoutier Abbey hostelry, a centuries-old building which, according to the sources presented, has evolved architecturally over several centuries ((Jean-Yves et al 2024: 8). These states of the building are represented visually through architectural elements based on their existence, location, shape and size, always in terms of what is presented as being plausible. This allows not only the creation of a matrix in which various categories are related to various architectural elements, but also a visual aid, through a chromatic spectrum, of the plausibility that the authors are aiming for. In short, this is an article that seeks to rethink the degree of knowledge we can obtain through 3D visualizations and that does not take models as static, but rather realities that must be explored, recycled and reinterpreted in the light of different data, users and future research. For this reason, it is a work of great relevance to theoretical advances in 3D modeling adapted to archaeology.

References Blaise, J.-Y., Dudek, I., Bergerot, L. and Gaël, S. (2024). Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research, Zenodo, 7983163, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10496540 John Maeda. (2006). The Laws of Simplicity. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. | Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research | J.Y Blaise, I.Dudek, L.Bergerot, G.Simon | <p> 3D virtual reconstructions have become over the last decades a classical mean to communicate about analysts’ visions concerning past stages of development of an edifice or a site. However, they still today remain quite often a one-s... |  | Computational archaeology, Spatial analysis | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-05-30 00:43:03 | View | |

13 Jan 2024

Dealing with post-excavation data: the Omeka S TiMMA web-databaseBastien Rueff https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7989904Managing Archaeological Data with Omeka SRecommended by Jonathan Hanna based on reviews by Electra Tsaknaki and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Electra Tsaknaki and 1 anonymous reviewer

Managing data in archaeology is a perennial problem. As the adage goes, every day in the field equates to several days in the lab (and beyond). For better or worse, past archaeologists did all their organizing and synthesis manually, by hand, but since the 1970s ways of digitizing data for long term management and analysis have gained increasing attention [1]. It is debatable whether this ever actually made things easier, particularly given the associated problem of sustainable maintenance and accessibility of the data. Many older archaeologists, for instance, still have reels and tapes full of data that now require a new form of archaeology to excavate (see [2] for an unrealized idea on how to solve this). Today, the options for managing digital archaeological data are limited only by one’s imagination. There are systems built specifically for archaeology, such as Arches [3], Ark [4], Codifi [5], Heurist [6], InTerris Registries [7], OpenAtlas [8], S-Archeo [9], and Wild Note [10], as well as those geared towards museum collections like PastPerfect [11] and CatalogIt [12], among others. There are also mainstream databases that can be adapted to archaeological needs like MS Access [13] and Claris FileMaker [14], as well as various web database apps that function in much the same way (e.g., Caspio [15], dbBee [16], Amazon's Simpledb [17], Sci-Note [18], etc.) — all with their own limitations in size, price, and utility. One could also write the code for specific database needs using pre-built frameworks like those in Ruby-On-Rails [19] or similar languages. And of course, recent advances in machine-learning and AI will undoubtedly bring new solutions in the near future. But let’s be honest — most archaeologists probably just use Excel. That's partly because, given all the options, it is hard to decide the best tool and whether its worth changing from your current system, especially given few real-world examples in the literature. Bastien Rueff’s new paper [20] is therefore a welcomed presentation on the use of Omeka S [21] to manage data collected for the Timbers in Minoan and Mycenaean Architecture (TiMMA) project. Omeka S is an open-source web-database that is based in PHP and MySQL, and although it was built with the goal of connecting digital cultural heritage collections with other resources online, it has been rarely used in archaeology. Part of the issue is that Omeka Classic was built for use on individual sites, but this has now been scaled-up in Omeka S to accommodate a plurality of sites. Some of the strengths of Omeka S include its open-source availability (accessible regardless of budget), the way it links data stored elsewhere on the web (keeping the database itself lean), its ability to import data from common file types, and its multi-lingual support. The latter feature was particularly important to the TiMAA project because it allowed members of the team (ranging from English, Greek, French, and Italian, among others) to enter data into the system in whatever language they felt most comfortable. However, there are several limitations specific to Omeka S that will limit widespread adoption. Among these, Omeka S apparently lacks the ability to export metadata, auto-fill forms, produce summations or reports, or provide basic statistical analysis. Its internal search capabilities also appear extremely limited. And that is not to mention the barriers typical of any new software, such as onerous technical training, questionable long-term sustainability, or the need for the initial digitization and formatting of data. But given the rather restricted use-case for Omeka S, it appears that this is not a comprehensive tool but one merely for data entry and storage that requires complementary software to carry out common tasks. As such, Rueff has provided a review of a program that most archaeologists will likely not want or need. But if one was considering adopting Omeka S for a project, then this paper offers critical information for how to go about that. It is a thorough overview of the software package and offers an excellent example of its use in archaeological practice.

[1] Doran, J. E., and F. R. Hodson (1975) Mathematics and Computers in Archaeology. Harvard University Press. [2] Snow, Dean R., Mark Gahegan, C. Lee Giles, Kenneth G. Hirth, George R. Milner, Prasenjit Mitra, and James Z. Wang (2006) Cybertools and Archaeology. Science 311(5763):958–959. [3] https://www.archesproject.org/ [4] https://ark.lparchaeology.com/ [5] https://codifi.com/ [6] https://heuristnetwork.org/ [7] https://www.interrisreg.org/ [8] https://openatlas.eu/ [9] https://www.skinsoft-lab.com/software/archaelogy-collection-management [10] https://wildnoteapp.com/ [11] https://museumsoftware.com/ [12] https://www.catalogit.app/ [13] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/access [14] https://www.claris.com/filemaker/ [15] https://www.caspio.com/ [16] https://www.dbbee.com/ [17] https://aws.amazon.com/simpledb/ [18] https://www.scinote.net/ [19] https://rubyonrails.org/ [20] Rueff, Bastien (2023) Dealing with Post-Excavation Data: The Omeka S TiMMA Web-Database. peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://zenodo.org/records/7989905 [21] https://omeka.org/

| Dealing with post-excavation data: the Omeka S TiMMA web-database | Bastien Rueff | <p>This paper reports on the creation and use of a web database designed as part of the TiMMA project with the Content Management System Omeka S. Rather than resulting in a technical manual, its goal is to analyze the relevance of using Omeka S in... |  | Buildings archaeology, Computational archaeology | Jonathan Hanna | 2023-05-31 12:16:25 | View | |

06 Oct 2023

Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice.Araar, Leila; Morgan, Colleen; Fowler, Louise https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7990581Understanding archaeological documentation through a participatory, arts-based approachRecommended by Nicolo Dell'Unto based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThis paper presents the use of a participatory arts-based methodology to understand how digital and analogue tools affect individuals' participation in the process of archaeological recording and interpretation. The preliminary results of this work highlight the importance of rethinking archaeologists' relationship with different recording methods, emphasising the need to recognise the value of both approaches and to adopt a documentation strategy that exploits the strengths of both analogue and digital methods. Although a larger group of participants with broader and more varied experience would have provided a clearer picture of the impact of technology on current archaeological practice, the article makes an important contribution in highlighting the complex and not always easy transition that archaeologists trained in analogue methods are currently experiencing when using digital technology. This is assessed by using arts-based methodologies to enable archaeologists to consider how digital technologies are changing the relationship between mind, body and practice. I found the range of experiences described in the papers by the archaeologists involved in the experiment particularly interesting and very representative of the change in practice that we are all experiencing. As the article notes, the two approaches cannot be directly compared because they offer different possibilities: if analogue methods foster a deeper connection with the archaeological material, digital documentation seems to be perceived as more effective in terms of data capture, information exchange and data sharing (Araar et al., 2023). It seems to me that an important element to consider in such a study is the generational shift and the incredible divide between native and non-native digital. The critical issues highlighted in the paper are central and provide important directions for navigating this ongoing (digital) transition. References Araar, L., Morgan, C. and Fowler, L. (2023) Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice., Zenodo, 7990581, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7990581 | Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice. | Araar, Leila; Morgan, Colleen; Fowler, Louise | <p>This paper uses a participatory, art-based methodology to understand how digital and analog tools impact individuals' experience and perceptions of archaeological recording. Body mapping involves the co-creation of life-sized drawings and narra... |  | Computational archaeology, Theoretical archaeology | Nicolo Dell'Unto | 2023-06-01 09:06:52 | View | |

02 Apr 2024

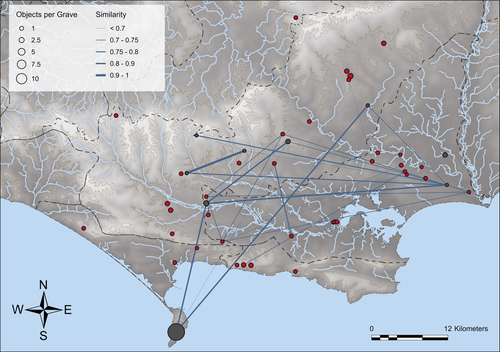

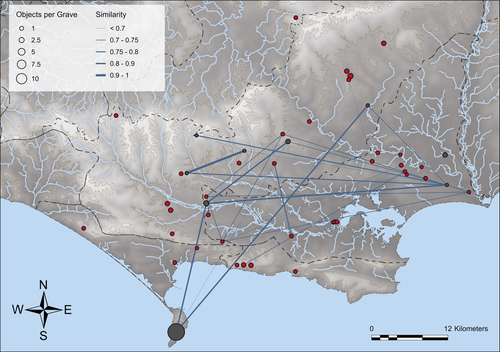

Similarity Network Fusion: Understanding Patterns and their Spatial Significance in Archaeological DatasetsTimo Geitlinger https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7998239A different approach to similarity networks in Archaeology - Similarity Network FusionRecommended by Joel Santos based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewerThis is a fascinating paper for anyone interested in network analysis or the chronology and cultures of the case study, namely the Late prehistoric burial sites in Dorset, for which the author’s approach allowed a new perspective over an already deeply studied area [1]. This paper's implementation of Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) is noteworthy. This method is typically utilized within genetic research but has yet to be employed in Archaeology. SNF has the potential to benefit Archaeology due to its unique capabilities and approach significantly. The author exhibits a deep and thorough understanding of previous investigations concerning material and similarity networks while emphasizing the innovative nature of this particular study. The SNF approach intends to improve a lack of the most used (in Archaeology) similarity coefficient, the Brainerd-Robinson, in certain situations, mainly in heterogenous and noisy datasets containing a small number of samples but a large number of measurements, scale differences, and collection biases, among other things. The SNF technique, demonstrated in the case study, effectively incorporates various similarity networks derived from different datatypes into one network. As shown during the Dorset case study, the SNF application has a great application in archaeology, even in already available data, allowing us to go further and bring new visions to the existing interpretations. As stated by the author, SNF shows its potential for other applications and fields in archaeology coping with similar datasets, such as archaeobotany or archaeozoology, and seems to complement different multivariate statistical approaches, such as correspondence or cluster analysis. This paper has been subject to two excellent revisions, which the author mostly accepted. One of the revisions was more technical, improving the article in the metadata part, data availability and clarification, etc. Although the second revision was more conceptual and gave some excellent technical inputs, it focused more on complementary aspects that will allow the paper to reach a wider audience. I vividly recommend its publication. References [1] Geitlinger, T. (2024). Similarity Network Fusion: Understanding Patterns and their Spatial Significance in Archaeological Datasets. Zenodo, 7998239, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7998239

| Similarity Network Fusion: Understanding Patterns and their Spatial Significance in Archaeological Datasets | Timo Geitlinger | <p>Since its earliest application in the 1970s, network analysis has become increasingly popular in both theoretical and GIS-based archaeology. Yet, applications of material networks remained relatively restricted. This paper describes a specific ... |  | Computational archaeology, Protohistory | Joel Santos | 2023-06-02 16:51:19 | View | |

02 Feb 2024

Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley CollectionRaykovska Miglena, Jones Kristen, Klecherova Hristina, Alexandrov Stefan, Petkov Nikolay, Hristova Tanya, Ivanov Georgi https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8027548Out of the storeroom and into the virtualRecommended by Jitte Waagen based on reviews by Alicia Walsh and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Alicia Walsh and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (Raykovska et al. 2023) discusses the digital documentation techniques and development of a virtual exhibition for artefacts retrieved from the necropolis of Baley, Bulgaria. The principal aim of this particular project is a solid one, trying to provide a solution to display artefacts that would otherwise remain hidden in museum storerooms. The paper describes how through a combination of 3D scanning and photogrammetry high quality 3D models have been produced, and provide content for an online virtual exhibition for the scientific community but also the larger public. It is a well-written and concise paper, in which the information on developed methods and techniques are transparently described, and various important aspects of digitization workflows, such as the importance of storing raw data, are addressed. The paper is a timely discussion on this subject, as strategies to develop digital artefact collections and what to do with those are increasingly being researched. Specifically, it discusses a workflow and its results, both in great detail. Although critical reflection on the process, goals and results from various perspectives would have been a valuable addition to the paper (cf., Jeffra 2020, Paardekoper 2019), it nonetheless provides a good practice example of how to approach the creation of a virtual museum. Those who consider projects concerning digital documentation of archaeological artefacts as well as the creation of virtual spaces to use those in for research, education or valorisation purposes would do well to read this paper carefully. References Jeffra, C., Hilditch, J., Waagen, J., Lanjouw, T., Stoffer, M., de Gelder, L., and Kim, M. J. (2020). Blending the Material and the Digital: A Project at the Intersection of Museum Interpretation, Academic Research, and Experimental Archaeology. The EXARC Journal, 2020(4). https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10541 Paardekooper, R.P. (2019). Everybody else is doing it, so why can’t we? Low-tech and High-tech approaches in archaeological Open-Air Museums. The EXARC Journal, 2019(4). https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10457/ Raykovska, M., Jones, K., Klecherova, H., Alexandrov, S., Petkov, N., Hristova, T., and Ivanov, G. (2023). Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley Collection. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10091870 | Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley Collection | Raykovska Miglena, Jones Kristen, Klecherova Hristina, Alexandrov Stefan, Petkov Nikolay, Hristova Tanya, Ivanov Georgi | <p>Over the past decade, virtual reality has been quickly growing in popularity across disciplines including the field of archaeology and cultural heritage. Despite numerous artifacts being uncovered each year by archaeological excavations around ... |  | Ceramics, Computational archaeology, Conservation/Museum studies | Jitte Waagen | 2023-06-12 14:02:44 | View | |

12 Apr 2024

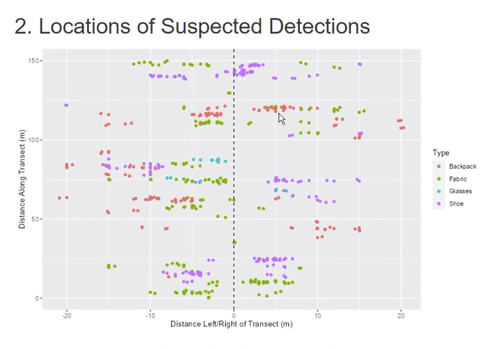

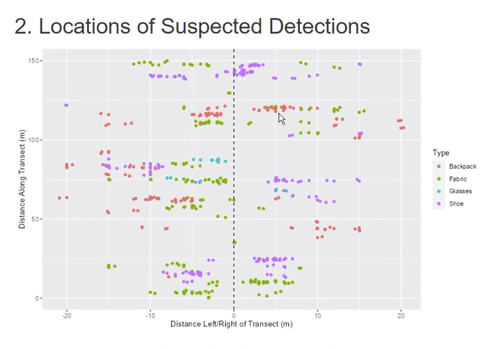

Survey Planning, Allocation, Costing and Evaluation (SPACE) Project: Developing a Tool to Help Archaeologists Conduct More Effective SurveysE. B. Banning, Steven Edwards, and Isaac Ullah https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8072178A new tool to increase the robustness of archaeological field surveyRecommended by Jitte Waagen based on reviews by Philip Verhagen and Tymon de Haas based on reviews by Philip Verhagen and Tymon de Haas

This well-written and interesting paper ‘Survey Planning, Allocation, Costing and Evaluation (SPACE) Project: Developing a Tool to Help Archaeologists Conduct More Effective Surveys’ deals with the development of a ‘modular, accessible, and simple web-based platform for survey planning and quality assurance’ in the area of pedestrian field survey methods (Banning et al. 2024). Although there have been excellent treatments of statistics in archaeological field survey (among which various by the first author: Banning 2020, 2021), and there is continuous methodological debate on platforms such as the International Mediterranean Survey Workshop (IMSW), in papers dealing with the current development and state of the field (Knodell et al. 2023), good practices (Attema et al. 2020) or the merits of a quantifying approach to archaeological densities (cf. de Haas et al. 2023), this paper rightfully addresses the lack of rigorous statistical approaches in archaeological field survey. As argued by several scholars such as Orton (2000), this mainly appears the result of lack of knowledge/familiarity/resources to bring in the required expertise etc. with the application of seemingly intricate statistics (cf. Waagen 2022). In this context this paper presents a welcome contribution to the feasibility of a robust archaeological field survey design. The SPACE application, under development by the authors, is introduced in this paper. It is a software tool that aims to provide different modules to assist archaeologists to make calculations for sample size, coverage, stratification, etc. under the conditions of survey goals and available resources. In the end, the goal is to ensure archaeological field surveys will attain their objectives effectively and permit more confidence in the eventual outcomes. The module concerning Sweep Widths, an issue introduced by the main author in 2006 (Banning 2006) is finished; the sweep width assessment is a methodology to calibrate one’s survey project for artefact types, landscape, visibility and person-bound performance, eventually increasing the quality (comparability) of the collected samples. This is by now a well-known calibration technique, yet little used, so this effort to make that more accessible is certainly laudable. An excellent idea, and another aim of this project, is indeed to build up a database with calibration data, so applying sweep-width corrections will become easier accessible to practitioners who lack time to set up calibration exercises. It will be very interesting to have a closer look at the eventual platform and to see if, and how, it will be adapted by the larger archaeological field survey community, both from an academic research perspective as from a heritage management point of view. I happily recommend this paper and all debate relating to it, including the excellent peer reviews of the manuscript by Philip Verhagen and Tymon de Haas (available as part of this PCI recommendation procedure), to any practitioner of archaeological field survey. References Attema, P., Bintliff, J., Van Leusen, P.M., Bes, P., de Haas, T., Donev, D., Jongman, W., Kaptijn, E., Mayoral, V., Menchelli, S., Pasquinucci, M., Rosen, S., García Sánchez, J., Luis Gutierrez Soler, L., Stone, D., Tol, G., Vermeulen, F., and Vionis. A. 2020. “A guide to good practice in Mediterranean surface survey projects”, Journal of Greek Archaeology 5, 1–62. https://doi.org/10.32028/9781789697926-2 Banning, E.B., Alicia L. Hawkins, S.T. Stewart, Sweep widths and the detection of artifacts in archaeological survey, Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 38, Issue 12, 2011, Pages 3447-3458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.08.007 Banning, E.B. 2020. Spatial Sampling. In: Gillings, M., Hacıgüzeller, P., Lock, G. (eds.) Archaeological Spatial Analysis. A Methodological Guide. Routledge. Banning, E.B. 2021. Sampled to Death? The Rise and Fall of Probability Sampling in Archaeology. American Antiquity, 86(1), 43-60. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2020.39 Banning, E. B. Steven Edwards, & Isaac Ullah. (2024). Survey Planning, Allocation, Costing and Evaluation (SPACE) Project: Developing a Tool to Help Archaeologists Conduct More Effective Surveys. Zenodo, 8072178, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8072178 Knodell, A.R., Wilkinson, T.C., Leppard, T.P. et al. 2023. Survey Archaeology in the Mediterranean World: Regional Traditions and Contributions to Long-Term History. J Archaeol Res 31, 263–329 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-022-09175-7 Orton, C. 2000. Sampling in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139163996 Waagen, J. 2022. Sampling past landscapes. Methodological inquiries into the bias problems of recording archaeological surface assemblages. PhD-Thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/e9cb922c-c7e4-40a1-b648-7b8065c46880 de Haas, T., Leppard, T. P., Waagen, J., & Wilkinson, T. (2023). Myopic Misunderstandings? A Reply to Meyer (JMA 35(2), 2022). Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 36(1), 127-137. https://doi.org/10.1558/jma.27148 | Survey Planning, Allocation, Costing and Evaluation (SPACE) Project: Developing a Tool to Help Archaeologists Conduct More Effective Surveys | E. B. Banning, Steven Edwards, and Isaac Ullah | <p>Designing an effective archaeological survey can be complicated and confidence that it was effective requires post-survey evaluation. The goal of SPACE is to develop software to facilitate survey designers’ decisions and partially automate tool... |  | Computational archaeology, Landscape archaeology | Jitte Waagen | 2023-06-28 13:42:28 | View | |

14 Mar 2024

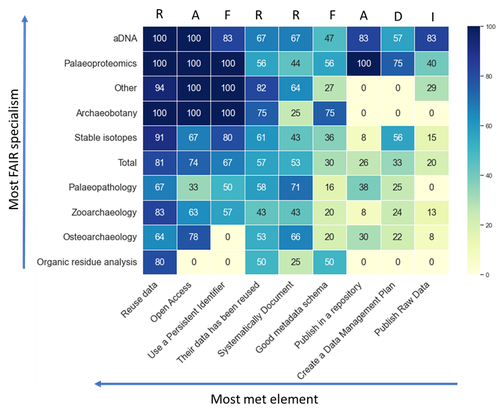

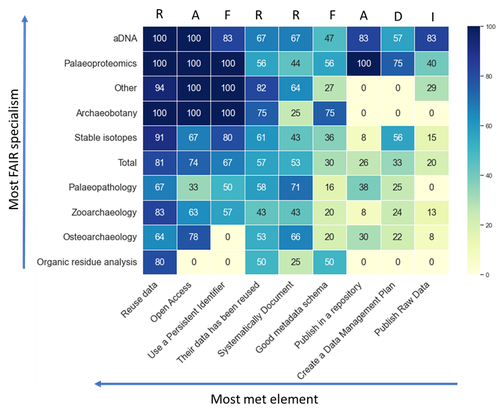

How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data ReusableLien-Talks, Alphaeus https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910FAIR data in bioarchaeology - where are we at?Recommended by Claudia Speciale based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers

The increasing reliance on digital and big data in archaeology is pushing the scientific community more and more to reconsider their storing and use [1, 2]. Furthermore, the openness and findability in the way these data are shared represent a key matter for the growth of the discipline, especially in the case of bioarchaeology and archaeological sciences [3]. In this paper, [4] the author presents the result of a survey targeted on UK bioarchaeologists and then extended worldwide. The paper maintains the structure of a report as it was intended for the conference it was part of (CAA 2023, Amsterdam) but it represents the first public outcome of an inquiry on the bioarchaeological scientific community. A reflection on ourselves and our own practices. Are all the disciplines adhering to the same policies? Do any bioarchaeologist use the same protocols and formats? Are there any differences in between the domains? Is the Needs Analysis fulfilling the questions? The results, obtained through an accurate screening to avoid distortions, are creating an intriguing picture on the current state of "fairness" and highlighting how Institutions' rules and policies can and should indicate the correct workflow to follow. In the end, the wide application of the FAIR principles will contribute significantly to the growth of the disciplines and to create an environment where the users are not just contributors, but primary beneficiaries of the system. [1] Huggett j. (2020). Is Big Digital Data Different? Towards a New Archaeological Paradigm, Journal of Field Archaeology, 45:sup1, S8-S17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2020.1713281 [2] Nicholson C., Kansa S., Gupta N. and Fernandez R. (2023). Will It Ever Be FAIR?: Making Archaeological Data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Advances in Archaeological Practice 11 (1): 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2022.40 [3] Plomp E., Stantis C., James H.F., Cheung C., Snoeck C., Kootker L., Kharobi A., Borges C., Reynaga D.K.M., Pospieszny Ł., Fulminante, F., Stevens, R., Alaica, A. K., Becker, A., de Rochefort, X. and Salesse, K. (2022). The IsoArcH initiative: Working towards an open and collaborative isotope data culture in bioarchaeology. Data in brief, 45, p.108595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2022.108595 [4] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable. Zenodo, 8139910, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910 | How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable | Lien-Talks, Alphaeus | <p>Bioarchaeology, which encompasses the study of ancient DNA, osteoarchaeology, paleopathology, palaeoproteomics, stable isotopes, and zooarchaeology, is generating an ever-increasing volume of data as a result of advancements in molecular biolog... |  | Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Zooarchaeology | Claudia Speciale | 2023-07-12 19:12:44 | View | |

20 Mar 2024

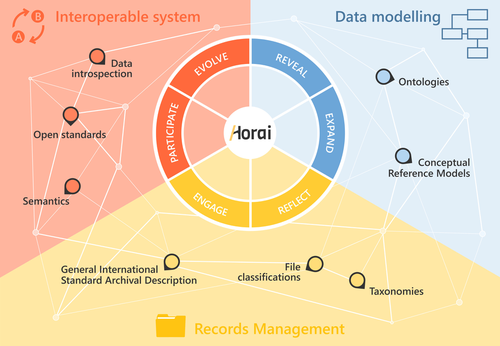

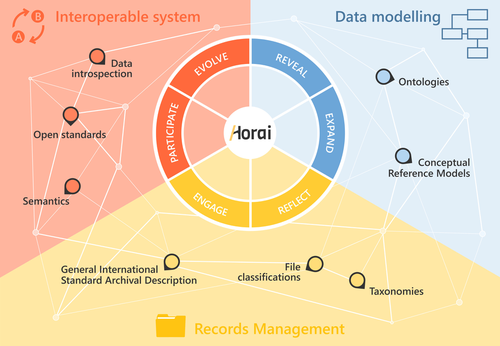

HORAI: An integrated management model for historical informationPablo del Fresno Bernal, Sonia Medina Gordo and Esther Travé Allepuz https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8185510A novel management model for historical informationRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Leandro Sánchez Zufiaurre and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper “HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information” presents a novel model for managing historical information. The study draws from an extensive indepth work in historical information management and a multi-disciplinary corpus of research ranging from heritage infrastructure research and practice to information studies and archival management literature. The paper ties into several key debates and discussions in the field showing awareness of the state-of-the-art of data management practice and theory. The authors argue for a new semantic data model HORAI and link it to a four-phase data management lifecycle model. The conceptual work is discussed in relation to three existing information systems partly predating and partly developed from the outset of the HORAI-model. While the paper shows appreciable understanding of the practical and theoretical state-of-the-art and the model has a lot of potential, in its current form it is still somewhat rough on the edges. Many of the both practical and theoretical threads introduced in the text warrant also more indepth consideration and it will be interesting to follow how the work will proceed in the future. For example, the comparison of the HORAI model and the ISAD(G): General International Standard Archival Description standard in the figure 1 is interesting but would require more elaboration. A slightly more thorough copyediting of the text would have also been helpful to make it more approachable. As a whole, in spite of the critique, I find both the paper and the model as valuable contributions to the literature and the practice of managing historical information. The paper reports thorough work, provides a lot of food for thought and several interesting lines of inquiry in the future. ReferencesDel Fresno Bernal, P., Medina Gordo, S. and Travé Allepuz, E. (2024). HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information. CAA 2023, Amsterdam, Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8185510 | HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information | Pablo del Fresno Bernal, Sonia Medina Gordo and Esther Travé Allepuz | <p>The archiving process goes beyond mere data storage, requiring a theoretical, methodological, and conceptual commitment to the sources of information. We present Horai as a semantic-based integration model designed to facilitate the development... |  | Computational archaeology, Spatial analysis | Isto Huvila | 2023-07-26 09:33:58 | View | |

11 Dec 2023

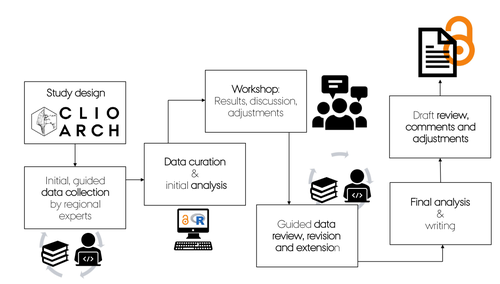

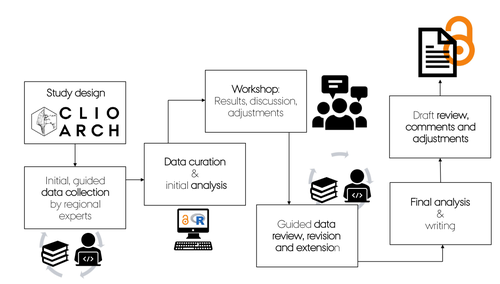

A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in EuropeFelix Riede, David N. Matzig, Miguel Biard, Philippe Crombé, Javier Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, Federica Fontana, Daniel Groß, Thomas Hess, Mathieu Langlais, Ludovic Mevel, William Mills, Martin Moník, Nicolas Naudinot, Caroline Posch, Tomas Rimkus, Damian Stefański, Hans Vandendriessche, Shumon T. Hussain https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8195587Questioning Final Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic cultural taxonomy with a data-driven statistical approachRecommended by Anaïs Vignoles based on reviews by Dirk Leder and 2 anonymous reviewersCultural taxonomies are an essential tool for archaeologists working with prehistoric material cultures as they have historically been used to create the basic analytical units for studying cultural evolution through time (de Mortillet, 1883 ; Breuil, 1913). This approach has its limits as the taxonomic units are essentially etic constructions, i.e., they are defined in a cultural context exterior to the one that produced the material culture on which they are based (e.g., Pesesse, 2019). But to approach questions related to cultural evolution, one has to define archaeological units with clear geographic and chronological delineations in order to be compared synchronically and diachronically (e.g., Willey and Philips, 1958). In « A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolitic/Earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe », F. Riede and colleagues propose a novel and interesting approach to question the end of the Palaeolithic and beginning of the Mesolithic’s « named archaeological cultures » (NACs) analytical pertinence (Riede et al., 2023). In this particular context, NACs are indeed very numerous (n = 86) and result from complex and regional research histories. It seems thus pertinent to question the extent to which the said NACs chronological and geographic patterns result from past cultural diversity and evolution, and are not artefacts of research. To do so, the authors adopted a data-driven approach that they describe in detail in the paper. First, they gathered an European data base of lithic tool-kit composition, blade and bladelet technology and armature morphology at 350 key sites considered representative of NACs, dated between 15 and 11 ka (Hussain et al., 2023). These data were then analyzed using geometric morphometrics and a set of statisticaal tests in order to 1) test the coherence of these taxonomic units, and 2) test the chronological change in artefact shape variation. The authors conclude that the data set is partially biased by reasearch practices and histories, as their data-driven approach has only partially replicated traditional NACs for the european Late Palaeolithic/Early Mesolithic. However, their analysis of armature shape evolution has shown a tendency to diversification overtime, a pattern that was already observed in more « traditional » approaches. This study is, in my opinion, an excellent contribution for a significant step in macro-regional approaches to the archaeological record: defining discrete archaeological units that serve as a basis for subsequent analyses aimed at delineating cultural evolutionary processes. The authors propose a carefully designed and statistically grounded procedure in order to achieve these definitions in the most replicable and explicit possible manner. Taking advantage of drawings as a primary source of information is also very original despite several limitations of this approach (such as the necessary selection of most typical artefacts to be represented, the incompleteness of data publication or the difficulty to access all published work across such a large geographic area). The results of the study are convincing enough to allow the authors to discuss the pertinence of European Late Paleo/Early Mesolithic NACs, the potential epistemological and historical factors that could affect this taxonomic framework, as well as to give more weight to the traditional hypothesis of lithic cultural diversification towards the end of the Pleistocene/beginning of the Holocene in Europe. I would also like to underline the authors’ important efforts to ensure transparence and replicability of their study, as well as the accessibility of the data, thanks to extensive supplementary data and a data paper describing their data set in detail. Anaïs L. Vignoles References Breuil, H. (1913). Les subdivisions du paléolithique supérieur et leur signification. In Congrès international d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques - compte-rendu de la XIVème session, tome 1:165‑238. Genève: Imprimerie Albert Kündig. Hussain, S. T., Riede, F., Matzig, D. N., Biard, M., Crombé, P., Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, J., Fontana, F., Groß, D., Hess, T., Langlais, M., Mevel, L., Mills, W., Moník, M., Naudinot, N., Posch, C., Rimkus, T., Stefański, D. and Vandendriessche, H. (2023). A Pan-European Dataset Revealing Variability in Lithic Technology, Toolkits, and Artefact Shapes ~15-11 Kya. Scientific Data 10 (1): 593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02500-9. Mortillet, G. (1883). Le Préhistorique, antiquité de l’homme. Reinwald. Paris. Pesesse, D. (2019). Analyser un silex, le façonner à nouveau ? Sur certains usages de la chaîne opératoire au Paléolithique supérieur. Techniques & culture, no 71: 74‑77. https://doi.org/10.4000/tc.11321. Riede, F., Matzig, D. N., Biard, M., Crombé, P., Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, J., Fontana, F., Groß, D., Hess, T., Langlais, M., Mevel, L., Mills, W., Moník, M., Naudinot, N., Posch, C., Rimkus, T., Stefański, D., Vandendriessche, H. and Hussain, S. T. (2023). A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe, Zenodo, 8195587., ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8195587 Willey, G. R. and Phillips, P. (1958). Method and Theory in American Archaeology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. | A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe | Felix Riede, David N. Matzig, Miguel Biard, Philippe Crombé, Javier Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, Federica Fontana, Daniel Groß, Thomas Hess, Mathieu Langlais, Ludovic Mevel, William Mills, Martin Moník, Nicolas Naudinot, Caroline Posch, Tomas Rimkus,... | <p>Archaeological systematics, together with spatial and chronological information, are commonly used to infer cultural evolutionary dynamics in the past. For the study of the Palaeolithic, and particularly the European Final Palaeolithic and earl... |  | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Mesolithic, Upper Palaeolithic | Anaïs Vignoles | 2023-07-29 16:06:17 | View | |

08 Feb 2024

CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient CoinsUlrike Peter, Claus Franke, Jan Köster, Karsten Tolle, Sebastian Gampe, Vladimir F. Stolba https://zenodo.org/records/8263517The valuable Corpus Nummorum: a not so Little MinionRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Fleur Kemmers and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Fleur Kemmers and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper under review/recommendation deals with Corpus Nummorum (Peter et al. 2024). The Corpus Nummorum (CN) is web portal for ancient Greek coins from various collections (https://www.corpus-nummorum.eu/). The CN is a database and research tool for Greek coins dating between 600 BCE to 300 CE. While many traditional collection databases aim at collecting coins, CN also includes coin dies, coin types and issues. It aims at achieving a complete online coin type catalogue. The paper is not a paper in a traditional sense, but presents the CN as a tool and shows the functionalities in the system. The relevance and the possibilities of the CN for numismatists is made clear in the paper and the merits are clear even for me as a Roman archaeologist and non-numismatist. The CN was presented as a poster at the CAA 2023 in Amsterdam during “S03. Our Little Minions pt. V: small tools with major impact”, organized by Moritz Mennenga, Florian Thiery, Brigit Danthine and myself (Mennenga et al. 2023). Little Minions help us significantly in our daily work as small self-made scripts, home-grown small applications and small hardware devices. They often reduce our workload or optimize our workflows, but are generally under-represented during conferences and not often presented to the outside world. Therefore, the Little Minions form a platform that enables researchers and software engineers to share these tools (Thiery, Visser and Mennenga 2021). Little Minions have become a well known happening within the CAA-community since we started this in 2018, also because we do not only allow 10-minute lightning talks, but also spontaneous stand-up presentations during the conference. A full list of all minions presented in the past, can be found online: https://caa-minions.github.io/minions/. In a strict sense the CN would not count as a Little Minion, because it is a large project consisting of many minions that help a numismatist in his/her daily work. The CN seems a very Big Minion in that sense. Personally, I am very happy to see the database being developed as a fully open system and that code can be found on Github (https://github.com/telota/corpus-nummorum-editor), and also made citable with citation information in GitHub (see https://citation-file-format.github.io/) and a version deposited in Zenodo with DOI (Köster and Franke 2024). In addition, the authors claim that the CN will be shared based on the FAIR-principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016, 2019). These guidelines are developed to improve the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse of digital data. I feel that CN will be a way forward in open numismatics and open archaeology. The CN is well known within the numismatist community and it was hard to find reviewers in this close community, because many potential reviewers work together with one or more of the authors, or are involved in the project. This also proves the relevance of the CN to the research community and beyond. Luckily, a Roman numismatist and a specialist in digital/computational archaeology were able to provide valuable feedback on the current paper. The reviewers only submitted feedback on the first version of the paper (Peter et al. 2023). The numismatist was positive on the content and the usefulness of CN for the discipline in general. However, she pointed out some important points that need to be addressed. The digital specialist was positive is various aspects, but also raised some important issues in relation to technical aspects and the explanation thereof. While both were positive on the project and the paper in general, both reviewers pointed out some issues that were largely addressed in the second version of this paper. The revised version was edited throughout and the paper was strongly improved. The Corpus Nummorum is well presented in this easy to read paper, although the explanations can sometimes be slightly technical. This paper gives a good introduction to the CN and I recommend this for publication. I sincerely hope that the CN will contribute and keep on contributing to the domains of numismatics, (digital) archaeology and open science in general. References Köster, J and Franke, C. 2024 Corpus Nummorum Editor. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10458195 Mennenga, M, Visser, RM, Thiery, F and Danthine, B. 2023 S03. Our Little Minions pt. V: small tools with major impact. In:. Book of Abstracts. CAA 2023: 50 Years of Synergy. Amsterdam: Zenodo. pp. 249–251. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7930991 Peter, U, Franke, C, Köster, J, Tolle, K, Gampe, S and Stolba, VF. 2023 CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.8263518 Peter, U., Franke, C., Köster, J., Tolle, K., Gampe, S. and Stolba, V. F. (2024). CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins, Zenodo, 8263517, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8263517 Thiery, F, Visser, RM and Mennenga, M. 2021 Little Minions in Archaeology An open space for RSE software and small scripts in digital archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.4575167 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Aalbersberg, IjJ, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, ’t Hoen, PAC, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Velterop, J, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2016 The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1): 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Jan Aalbersberg, I, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, Hoen, PAC ’t, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Jan Velterop, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2019 Addendum: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 6(1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0009-6 | CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins | Ulrike Peter, Claus Franke, Jan Köster, Karsten Tolle, Sebastian Gampe, Vladimir F. Stolba | <p>CORPUS NUMMORUM indexes ancient Greek coins from various landscapes and develops typologies. The coins and coin types are published on the multilingual website www.corpus-nummorum.eu utilizing numismatic authority data and adhering to FAIR prin... |  | Antiquity, Classic | Ronald Visser | 2023-08-18 17:37:51 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer