KORNFELD Marcel

- PaleoIndian Research Laboratory, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming, United States of America

- Lithic technology, North America, Peopling, Taphonomy, Theoretical archaeology, Traceology, Zooarchaeology

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Reviews: 0

Recommendation: 1

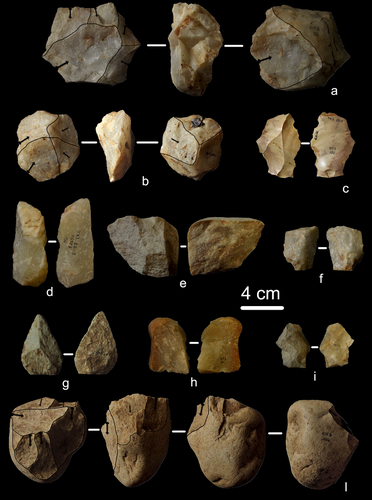

First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy)

Not Simply the Surface: Manifesting Meaning in What Lies Above.

Recommended by Marcel Kornfeld based on reviews by Lawrence Todd, Jason LaBelle and 2 anonymous reviewersThe archaeological record comes in many forms. Some, such as buried sites from volcanic eruptions or other abrupt sedimentary phenomena are perhaps the only ones that leave relatively clean snapshots of moments in the past. And even in those cases time is compressed. Much, if not all other archaeological record is a messy affair. Things, whatever those things may be, artifacts or construction works (i.e., features), moved, modified, destroyed, warped and in a myriad of ways modified from their behavioral contexts. Do we at some point say the record is worthless? Not worth the effort or continuing investigation. Perhaps sometimes this may be justified, but as Daffara and colleagues show, heavily impacted archaeological remains can give us clues and important information about the past. Thoughtful and careful prehistorians can make significant contributions from what appear to be poor archaeological records.

In the case of Daffara and colleagues, a number of important theoretical cross-sections can be recognized. For a long time surface archaeology was thought of simply as a way of getting a preliminary peak at the subsurface. From some of the earliest professional archaeologists (e.g., Kidder 1924, 1931; Nelson 1916) to the New Archaeologists of the 1960s, the link between the surface and subsurface was only improved in precision and systematization (Binford et al. 1970). However, at Hatchery West Binford and colleagues not only showed that surface material can be used more reliably to get at the subsurface, but that substantive behavioral inferences can be made with the archaeological record visible on the surface.

Much more important are the behavioral implications drawn from surface material. I am not sure we can cite the first attempts at interpreting prehistory from the surface manifestations of the archaeological record, but a flurry of such approaches proliferated in the 1970s and beyond (Dunnell and Dancey 1983; Ebert 1992; Foley 1981). Off-site archaeology, non-site archaeology, later morphing into landscape archaeology all deal strictly with surface archaeological record to aid in understanding the past. With the current paper, Daffara and colleagues (2024) are clearly in this camp. Although still not widely accepted, it is clear that some behaviors (parts of systems) can only be approached from surface archaeological record. It is very unlikely that a future archaeologist will be able to excavate an entire human social/cultural system; people moving from season to season, creating multiple long and short term camps, travelling, procuring resources, etc. To excavate an entire system one would need to excavate 20,000 km2 or some similarly impossible task. Even if it was physically possible to excavate such an enormous area, it is very likely that some of contextual elements of any such system will be surface manifestations.

Without belaboring the point, surface archaeological record yields data like any other archaeological record. We must contextual the archaeological artifacts or features weather they come from surface or below. Daffara and colleagues show us that we can learn about deep prehistory of northern Italy, with collections that were unsystematically collected, biased by agricultural as well as other land deformations agents. They carefully describe the regional prehistory as we know it, in particular specific well documented sites and assemblages as a means of applying such knowledge to less well controlled or uncontrolled collections.

References

Binford, L., Binford, R. S. R., Whallon, R. and Hardin, M. A. (1970). Archaeology of Hatchery West. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, No. 24, Washington D.C.

Daffara, S., Giraudi, C., Berruti, G. L. F., Caracausi, S. and Garanzini, F. (2024). First evidence of a Palaeolithic frequentation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy), OSF Preprints, pz4uf, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4uf

Dunnell, R. C. and Dancey, W. S. (1983). The siteless survey: a regional scale data collection strategy. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 6, edited by Michael B. Schiffer, pp. 267-287. Academic Press, New York.

Ebert, J. I. (1992). Distributional Archaeology. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Foley, R. A. (1981). Off site archaeology and human adaptation in eastern Africa: An analysis of regional artefact density in the Amboseli, Southern Kenya. British Archaeological Reports International Series 97. Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 3. Oxford England.

Kidder, A. V. (1924). An Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology, With a Preliminary Account of the Excavations at Pecos. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy, no. 1. New Haven, Connecticut.

Kidder, A. V. (1931). The Pottery of Pecos, vol. 1. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy. New Haven, Connecticut.

Nelson, N. (1916). Chronology of the Tano Ruins, New Mexico. American Anthropologist 18(2):159-180.