Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * ▲ | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

05 Jan 2024

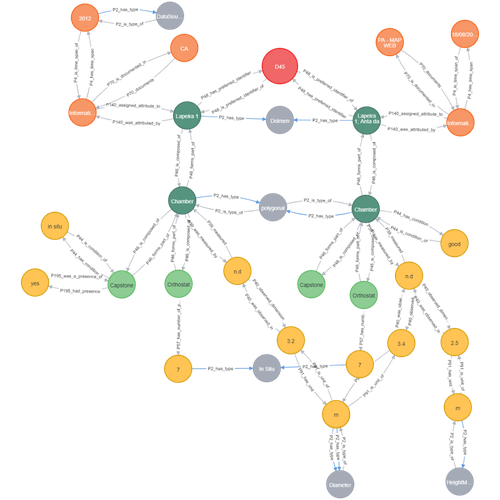

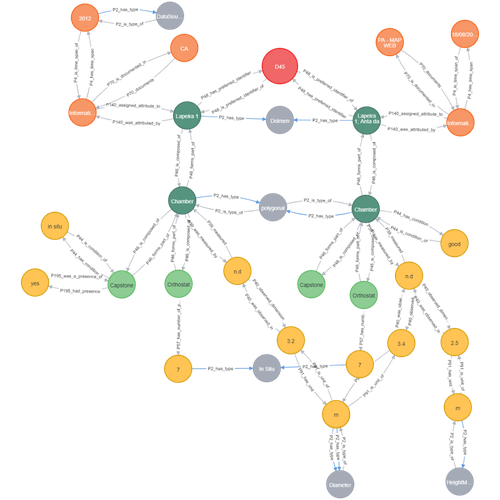

Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graphAriele Câmara, Ana de Almeida, João Oliveira https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981230Informative description of a project implementing a CIDOC-CRM based native graph database for representing megalithic informationRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper “Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph” describes an interesting endeavour of developing and implementing a CIDOC-CRM based knowledge graph using a native graph database (Neo4J) to represent megalithic information (Câmara et al. 2023). While there are earlier examples of using native graph databases and CIDOC-CRM in diverse heritage contexts, the present paper is useful addition to the literature as a detailed description of an implementation in the context of megalithic heritage. The paper provides a demonstration of a working implementation, and guidance for future projects. The described project is also documented to an extent that the paper will open up interesting opportunities to compare the approach to previous and forthcoming implementations. The same applies to the knowledge graph and use of CIDOC-CRM in the project. Readers interested in comparing available technologies and those who are developing their own knowledge graphs might have benefited of a more detailed description of the work in relation to the current state-of-the-art and what the use of a native graph database in the built-heritage contexts implies in practice for heritage documentation beyond that it is possible and it has potentially meaningful performance-related advantages. While also the reasons to rely on using plain CIDOC-CRM instead of extensions could have been discussed in more detail, the approach demonstrates how the plain CIDOC-CRM provides a good starting point to satisfy many heritage documentation needs. As a whole, the shortcomings relating to positioning the work to the state-of-the-art and reflecting and discussing design choices do not reduce the value of the paper as a valuable case description for those interested in the use of native graph databases and CIDOC-CRM in heritage documentation in general and the documentation of megalithic heritage in particular. ReferencesCâmara, A., de Almeida, A. and Oliveira, J. (2023). Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph, Zenodo, 7981230, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981230 | Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph | Ariele Câmara, Ana de Almeida, João Oliveira | <p>This paper presents a method to store information about megalithic monuments' building components as graph nodes in a knowledge graph (KG). As a case study we analyse the dolmens from the region of Pavia (Portugal). To build the KG, information... |  | Computational archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-29 13:46:49 | View | |

02 Jan 2024

Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenariosDiamanti, Eleni; Yip, Mauhing; Stahl, Annette; Ødegård, Øyvind https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305098Beyond Deep Blue: Underwater robotics, simulations and archaeologyRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Marco Moderato and 1 anonymous reviewerDiamanti et al. (2024) is a significant contribution to the field of underwater robotics and their use in archaeology, with an innovative approach to some major problems in the deployment of said technologies. It identifies issues when it comes to approaching Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) sites and does so through an interest in the combination of data, maneuverability, and the interpretation provided by the instruments that archaeologists operate. The article's motives are clear: it is not enough to find the means to reach these sites, but rather is fundamental to take a step forward in methodology and how we can safeguard certain aspects of data recovery with robust mission planning. To this end, the article does not fail to highlight previous contributions, in an intertwined web of references that demonstrate the marked evolution of the use of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), Remote Operated Vehicles (ROVs), Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Autonomous Surface Vehicles (ASVs), which are growing exponentially in use (see Kapetanović et al. 2020). It should be emphasized that the notion of ‘aquatic environment’ used here is quite broad and is not limited to oceanic or maritime environments, which allows for a larger perspective on distinct technologies that proliferate in underwater archaeology. There is also a relevant discussion on the typologies of sensors and how these autonomous vehicles obtain their data, where are debated Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) and LiDAR systems. Thus, the authors of this article propose the creation of a model that acquires data through simulations, which allows for a better understanding of what a real mission presupposes in the field. Their tripartite method - pre-mission planning; mission plan and post-mission plan - offers a performing algorithm that simplifies and provides reliability to all the parts of the intervention. The use of real cases to create simulation models allows for a substantial approximation to common practice in underwater environments. And yet, the article is at its most innovative status when it combines all the elements it sets out to explore. It could simply focus on the methodological or planning component, on obtaining data, or on theoretical problems. But it goes further, which makes this approach more complete and of interest to the archaeological community. By not taking any part as isolated, the problems and possible solutions arising from the course of the mission are carried over from one parameter to another, where details are worked upon and efficiency goals are set. One of the most significant cases is the tuning of ocean optics in aquatic environments according to the idiosyncracies of real cases (Diamanti et al. 2024: 8), a complex endeavor but absolutely necessary in order to increase the informative potential of the simulation. The exploration of various data capture models is also welcome, for the purposes of comparison and adaptation on a case-by-case basis. The brief theoretical reflection offered at the end of the article dwells in all these points and problematizes the difference between terrestrial and aquatic archaeology. In fact, the distinction does not only exist in the technical component, as although it draws in theoretical elements from archaeology that is carried out on land (see Krieger 2012 for this matter), the problems and interpretations are shaped by different factors and therefore become unique (Diamanti et al 2024: 15). The future, according to the authors, lies in increasing the autonomy of these vehicles so that the human element does not have to make decisions in a systematic way. It is in that note, and in order for that path to become closer to reality, that we strongly recommend this article for publication, in conjunction with the comments of the reviewers. We hope that its integrated approach, which brings together methods, theories and reflections, can become a broader modus operandi within the field of underwater robotics applied to archaeology. References: Diamanti, E., Yip, M., Stahl, A. and Ødegård, Ø. (2024). Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenarios, Zenodo, 8305098, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305098 Kapetanović, N., Vasilijević, A., Nađ, Đ., Zubčić, K., and Mišković, N. (2020). Marine Robots Mapping the Present and the Past: Unraveling the Secrets of the Deep. Remote Sensing, 12(23), 3902. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/rs12233902 Krieger, W. H. (2012). Theory, Locality, and Methodology in Archaeology: Just Add Water? HOPOS: The Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science, 2(2), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1086/666956

| Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenarios | Diamanti, Eleni; Yip, Mauhing; Stahl, Annette; Ødegård, Øyvind | <p>This paper presents a novel method for visual-based 3D mapping of underwater cultural heritage sites through marine robotic operations. The proposed methodology addresses the three main stages of an underwater robotic mission, specifically the ... | Computational archaeology, Remote sensing | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-08-31 16:03:10 | View | ||

03 Feb 2024

Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern CroatiaSosic Klindzic Rajna; Vuković Miroslav; Kalafatić Hrvoje; Šiljeg Bartul https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970703What lies on top lies also beneath? Connecting crop surface modelling to buried archaeology mapping.Recommended by Markos Katsianis based on reviews by Ian Moffat and Geert Verhoeven based on reviews by Ian Moffat and Geert Verhoeven

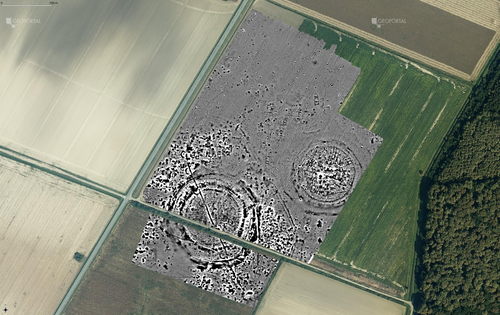

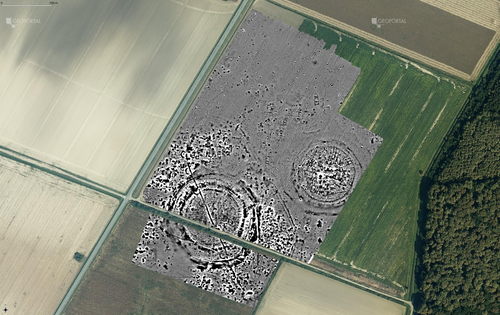

This paper (Sosic et al. 2024) explores the Neolithic landscape of the Sopot culture in Đakovština, Eastern Slavonija, revealing a network of settlements through a multi-faceted approach that combines aerial archaeology, magnetometry, excavation, and field survey. This strategy facilitates scalable research tailored to the particularities of each site and allows for improved representations of buried archaeology with minimal intrusion. Using the site of Tomašanci-Dubrava as an example of the overall approach, the study further explores the use of drone imagery for 3D surface modeling, revealing a consistent correlation between crop surface elevation during full plant growth and ground terrain after ploughing, attributed to subsurface archaeological features. Results are correlated with magnetic survey and test-pitting data to validate the micro-topography and clarify the relationship between different subsurface structures. The results obtained are presented in a comprehensive way, including their source data, and are contextualized in relation to conventional cropmark detection approaches and expectations. I found this aspect very interesting, since the crop surface and terrain models contradict typical or textbook examples of cropmark detection, where the vegetation is projected to appear higher in ditches and lower in areas with buried archaeology (Renfrew & Bahn 2016, 82). Regardless, the findings suggest the potential for broader applications of crop surface or canopy height modelling in landscape wide surveys, utilizing ALS data or aerial photographs. It seems then that the authors make a valid argument for a layered approach in landscape-based site detection, where aerial imagery can be used to accurately map the topography of areas of interest, which can then be further examined at site scale using more demanding methods, such as geophysical survey and excavation. This scalability enhances the research's relevance in broader archaeological and geographical contexts and renders it a useful example in site detection and landscape-scale mapping. References Renfrew, C. and Bahn, P. (2016). Archaeology: theories, methods and practice. Thames and Hudson. Sosic Klindzic, R., Vuković, M., Kalafatić, H. and Šiljeg, B. (2024). Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern Croatia, Zenodo, 7970703, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970703 | Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern Croatia | Sosic Klindzic Rajna; Vuković Miroslav; Kalafatić Hrvoje; Šiljeg Bartul | <p>This paper presents the results of a study on the neolithic landscape of the Sopot culture in the area of Đakovština in Eastern Slavonija. A vast network of settlements was uncovered using aerial archaeology, which was further confirmed and chr... |  | Landscape archaeology, Neolithic, Remote sensing, Spatial analysis | Markos Katsianis | 2023-09-01 12:57:04 | View | |

13 Jan 2024

Dealing with post-excavation data: the Omeka S TiMMA web-databaseBastien Rueff https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7989904Managing Archaeological Data with Omeka SRecommended by Jonathan Hanna based on reviews by Electra Tsaknaki and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Electra Tsaknaki and 1 anonymous reviewer

Managing data in archaeology is a perennial problem. As the adage goes, every day in the field equates to several days in the lab (and beyond). For better or worse, past archaeologists did all their organizing and synthesis manually, by hand, but since the 1970s ways of digitizing data for long term management and analysis have gained increasing attention [1]. It is debatable whether this ever actually made things easier, particularly given the associated problem of sustainable maintenance and accessibility of the data. Many older archaeologists, for instance, still have reels and tapes full of data that now require a new form of archaeology to excavate (see [2] for an unrealized idea on how to solve this). Today, the options for managing digital archaeological data are limited only by one’s imagination. There are systems built specifically for archaeology, such as Arches [3], Ark [4], Codifi [5], Heurist [6], InTerris Registries [7], OpenAtlas [8], S-Archeo [9], and Wild Note [10], as well as those geared towards museum collections like PastPerfect [11] and CatalogIt [12], among others. There are also mainstream databases that can be adapted to archaeological needs like MS Access [13] and Claris FileMaker [14], as well as various web database apps that function in much the same way (e.g., Caspio [15], dbBee [16], Amazon's Simpledb [17], Sci-Note [18], etc.) — all with their own limitations in size, price, and utility. One could also write the code for specific database needs using pre-built frameworks like those in Ruby-On-Rails [19] or similar languages. And of course, recent advances in machine-learning and AI will undoubtedly bring new solutions in the near future. But let’s be honest — most archaeologists probably just use Excel. That's partly because, given all the options, it is hard to decide the best tool and whether its worth changing from your current system, especially given few real-world examples in the literature. Bastien Rueff’s new paper [20] is therefore a welcomed presentation on the use of Omeka S [21] to manage data collected for the Timbers in Minoan and Mycenaean Architecture (TiMMA) project. Omeka S is an open-source web-database that is based in PHP and MySQL, and although it was built with the goal of connecting digital cultural heritage collections with other resources online, it has been rarely used in archaeology. Part of the issue is that Omeka Classic was built for use on individual sites, but this has now been scaled-up in Omeka S to accommodate a plurality of sites. Some of the strengths of Omeka S include its open-source availability (accessible regardless of budget), the way it links data stored elsewhere on the web (keeping the database itself lean), its ability to import data from common file types, and its multi-lingual support. The latter feature was particularly important to the TiMAA project because it allowed members of the team (ranging from English, Greek, French, and Italian, among others) to enter data into the system in whatever language they felt most comfortable. However, there are several limitations specific to Omeka S that will limit widespread adoption. Among these, Omeka S apparently lacks the ability to export metadata, auto-fill forms, produce summations or reports, or provide basic statistical analysis. Its internal search capabilities also appear extremely limited. And that is not to mention the barriers typical of any new software, such as onerous technical training, questionable long-term sustainability, or the need for the initial digitization and formatting of data. But given the rather restricted use-case for Omeka S, it appears that this is not a comprehensive tool but one merely for data entry and storage that requires complementary software to carry out common tasks. As such, Rueff has provided a review of a program that most archaeologists will likely not want or need. But if one was considering adopting Omeka S for a project, then this paper offers critical information for how to go about that. It is a thorough overview of the software package and offers an excellent example of its use in archaeological practice.

[1] Doran, J. E., and F. R. Hodson (1975) Mathematics and Computers in Archaeology. Harvard University Press. [2] Snow, Dean R., Mark Gahegan, C. Lee Giles, Kenneth G. Hirth, George R. Milner, Prasenjit Mitra, and James Z. Wang (2006) Cybertools and Archaeology. Science 311(5763):958–959. [3] https://www.archesproject.org/ [4] https://ark.lparchaeology.com/ [5] https://codifi.com/ [6] https://heuristnetwork.org/ [7] https://www.interrisreg.org/ [8] https://openatlas.eu/ [9] https://www.skinsoft-lab.com/software/archaelogy-collection-management [10] https://wildnoteapp.com/ [11] https://museumsoftware.com/ [12] https://www.catalogit.app/ [13] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/access [14] https://www.claris.com/filemaker/ [15] https://www.caspio.com/ [16] https://www.dbbee.com/ [17] https://aws.amazon.com/simpledb/ [18] https://www.scinote.net/ [19] https://rubyonrails.org/ [20] Rueff, Bastien (2023) Dealing with Post-Excavation Data: The Omeka S TiMMA Web-Database. peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://zenodo.org/records/7989905 [21] https://omeka.org/

| Dealing with post-excavation data: the Omeka S TiMMA web-database | Bastien Rueff | <p>This paper reports on the creation and use of a web database designed as part of the TiMMA project with the Content Management System Omeka S. Rather than resulting in a technical manual, its goal is to analyze the relevance of using Omeka S in... |  | Buildings archaeology, Computational archaeology | Jonathan Hanna | 2023-05-31 12:16:25 | View | |

02 May 2024

Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the MuseumAntonis G. Dimitriou, Stella Papadopoulou, Maria Dermenoudi, Angeliki Moneda, Vasiliki Drakaki, Andreana Malama, Alexandros Filotheou, Aristidis Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, Anastasios Tzitzis, Spyros Megalou, Stavroula Siachalou, Aggelos Bletsas, Traianos Yioultsis, Anna Maria Velentza, Sofia Pliasa, Nikolaos Fachantidis, Evangelia Tsangaraki, Dimitrios Karolidis, Charalampos Tsoungaris, Panagiota Balafa and Angeliki Koukouvou https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7805387Social Robotics in the Museum: a case for human-robot interaction using RFID TechnologyRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and Alexis PantosThe paper “Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum” (Dimitriou et al 2023) is a relevant contribution to museology and an interface between the public, archaeological discourse and the field of social robotics. It deals well with these themes and is concise in its approach, with a strong visual component that helps the reader to understand what is at stake. The option of demonstrating the different steps that lead to the final construction of the robot is appropriate, so that it is understood that it really is a linked process and not simple tasks that have no connection. The use of RFID technology for topological movement of social robots has been continuously developed (e.g., Corrales and Salichs 2009; Turcu and Turcu 2012; Sequeira and Gameiro 2017) and shown to have advantages for these environments. Especially in the context of a museum, with all the necessary precautions to avoid breaching the public's privacy, RFID labels are a viable, low-cost solution, as the authors point out (Dimitriou et al 2023), and, above all, one that does not require the identification of users. It is in itself part of an ambitious project, since the robot performs several functions and not just one, a development compared to other currents within social robotics (see Hellou et al 2022: 1770 for a description of the tasks given to robots in museums). The robotic system itself also makes effective use of the localization system, both physically, by RFID labels and by knowing how to situate itself with the public visiting the museum, adapting to their needs, which is essential for it to be successful (see Gasteiger, Hellou and Ahn 2022: 690 for the theme of localization). Archaeology can provide a threshold of approaches when it comes to social robotics and this project demonstrates that, bringing together elements of interaction, education and mobility in a single method. Hence, this is a paper with great merit and deserves to be recommended as it allows us to think of the museum as a space where humans and non-humans can converge to create intelligible discourses, whether in the historical, archaeological or cultural spheres. References Dimitriou, A. G., Papadopoulou, S., Dermenoudi, M., Moneda, A., Drakaki, V., Malama, A., Filotheou, A., Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, A., Tzitzis, A., Megalou, S., Siachalou, S., Bletsas, A., Yioultsis, T., Velentza, A. M., Pliasa, S., Fachantidis, N., Tsagkaraki, E., Karolidis, D., Tsoungaris, C., Balafa, P. and Koukouvou, A. (2024). Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum. Zenodo, 7805387, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7805387 Corrales, A. and Salichs, M.A. (2009). Integration of a RFID System in a Social Robot. In: Kim, JH., et al. Progress in Robotics. FIRA 2009. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 44. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03986-7_8 Gasteiger, N., Hellou, M. and Ahn, H.S. (2023). Factors for Personalization and Localization to Optimize Human–Robot Interaction: A Literature Review. Int J of Soc Robotics 15, 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-021-00811-8 Hellou, M., Lim, J., Gasteiger, N., Jang, M. and Ahn, H. (2022). Technical Methods for Social Robots in Museum Settings: An Overview of the Literature. Int J of Soc Robotics 14, 1767–1786 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-022-00904-y Sequeira, J. S., and Gameiro, D. (2017). A Probabilistic Approach to RFID-Based Localization for Human-Robot Interaction in Social Robotics. Electronics, 6(2), 32. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/electronics6020032 Turcu, C. and Turcu, C. (2012). The Social Internet of Things and the RFID-based robots. In: IV International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2012, pp. 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUMT.2012.6459769 | Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum | Antonis G. Dimitriou, Stella Papadopoulou, Maria Dermenoudi, Angeliki Moneda, Vasiliki Drakaki, Andreana Malama, Alexandros Filotheou, Aristidis Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, Anastasios Tzitzis, Spyros Megalou, Stavroula Siachalou, Aggelos Bletsas, ... | <p>This paper summarizes the adoption of new technologies in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece. RFID technology has been adopted. RFID tags have been attached to the artifacts. This allows for several interactions, including tracki... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Remote sensing | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-04-10 14:04:23 | View | |

06 Oct 2023

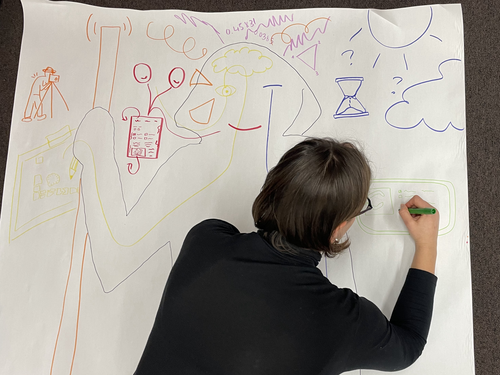

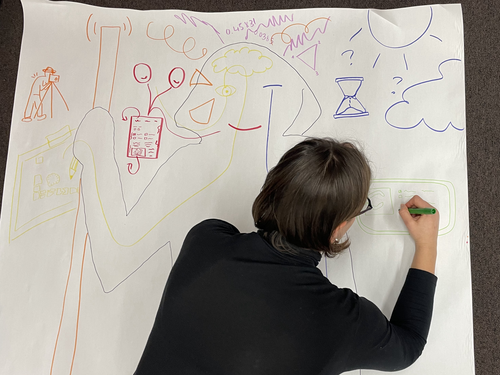

Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice.Araar, Leila; Morgan, Colleen; Fowler, Louise https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7990581Understanding archaeological documentation through a participatory, arts-based approachRecommended by Nicolo Dell'Unto based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThis paper presents the use of a participatory arts-based methodology to understand how digital and analogue tools affect individuals' participation in the process of archaeological recording and interpretation. The preliminary results of this work highlight the importance of rethinking archaeologists' relationship with different recording methods, emphasising the need to recognise the value of both approaches and to adopt a documentation strategy that exploits the strengths of both analogue and digital methods. Although a larger group of participants with broader and more varied experience would have provided a clearer picture of the impact of technology on current archaeological practice, the article makes an important contribution in highlighting the complex and not always easy transition that archaeologists trained in analogue methods are currently experiencing when using digital technology. This is assessed by using arts-based methodologies to enable archaeologists to consider how digital technologies are changing the relationship between mind, body and practice. I found the range of experiences described in the papers by the archaeologists involved in the experiment particularly interesting and very representative of the change in practice that we are all experiencing. As the article notes, the two approaches cannot be directly compared because they offer different possibilities: if analogue methods foster a deeper connection with the archaeological material, digital documentation seems to be perceived as more effective in terms of data capture, information exchange and data sharing (Araar et al., 2023). It seems to me that an important element to consider in such a study is the generational shift and the incredible divide between native and non-native digital. The critical issues highlighted in the paper are central and provide important directions for navigating this ongoing (digital) transition. References Araar, L., Morgan, C. and Fowler, L. (2023) Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice., Zenodo, 7990581, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7990581 | Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice. | Araar, Leila; Morgan, Colleen; Fowler, Louise | <p>This paper uses a participatory, art-based methodology to understand how digital and analog tools impact individuals' experience and perceptions of archaeological recording. Body mapping involves the co-creation of life-sized drawings and narra... |  | Computational archaeology, Theoretical archaeology | Nicolo Dell'Unto | 2023-06-01 09:06:52 | View | |

06 Aug 2023

A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional ProjectScott Madry, Gregory Jansen, Seth Murray, Elizabeth Jones, Lia Willcoxon, Ebtihal Alhashem https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7967035A meticulous description of archiving research data from a long-running landscape research projectRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and Iwona DudekThe paper “A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project” (Madry et al., 2023) describes practices, challenges and opportunities encountered in digital archiving of a landscape research project running in Burgundy, France for more than 45 years. As an unusually long-running multi-disciplinary undertaking working with a large variety of multi-modal digital and non-digital data, the Burgundy project has lived through the development of documentation and archiving technologies from the 1970s until today and faced many of the challenges relating to data management, preservation and migration. The major strenght of the paper is that it provides a detailed description of the evolution of digital data archiving practices in the project including considerations about why some approaches were tested and abandoned. This differs from much of the earlier literature where it has been more common to describe individual solutions how digital archiving was either planned or was performed at one point of time. A longitudinal description of what was planned, how and why it has worked or failed so far, as described in the paper, provides important insights in the everyday hurdles and ways forward in digital archiving. As a description of a digital archiving initiative, the paper makes a valuable contribution for the data archiving scholarship as a case description of practices and considerations in one research project. For anyone working with data management in a research project either as a researcher or data manager, the text provides useful advice on important practical matters to consider ahead, during and after the project. The main advice the authors are giving, is to plan and act for data preservation from the beginning of the project rather than doing it afterwards. To succeed in this, it is crucial to be knowledgeable of the key concepts of data management—such as “digital data fixity, redundant backups, paradata, metadata, and appropriate keywords” as the authors underline—including their rationale and practical implications. The paper shows also that when and if unexpected issues raise, it is important to be open for different alternatives, explore ways forward, and in general be flexible. The paper makes also a timely contribution to the discussion started at the session “Archiving information on archaeological practices and work in the digital environment: workflows, paradata and beyond” at the Computer Applications and Quantitative 2023 conference in Amsterdam where it was first presented. It underlines the importance of understanding and communicating the premises and practices of how data was collected (and made) and used in research for successful digital archiving, and the similar pertinence of documenting digital archiving processes to secure the keeping, preservation and effective reuse of digital archives possible. ReferencesMadry, S., Jansen, G., Murray, S., Jones, E., Willcoxon, L. and Alhashem, E. (2023) A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project, Zenodo, 7967035, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7967035 | A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project | Scott Madry, Gregory Jansen, Seth Murray, Elizabeth Jones, Lia Willcoxon, Ebtihal Alhashem | <p>This paper will consider the practical realities that have been encountered while seeking to create a usable Digital Archiving system of a long-term and multi-participant research project. The lead author has been involved in archaeologic... |  | Computational archaeology, Environmental archaeology, Landscape archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-24 18:46:34 | View | |

28 Feb 2024

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and DutchAlex Brandsen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10610882Multilingual Named Entity Recognition in archaeology: an approach based on deep learningRecommended by Maria Pia di Buono based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch” (Brandsen 2024) explores the use of BERT-based models for Named Entity Recognition (NER) in archaeology across three languages: English, German, and Dutch. It introduces six models trained and fine-tuned on archaeological literature, followed by the presentation and evaluation of three models specifically tailored for NER tasks. The focus on multilingualism enhances the applicability of the research, while the meticulous evaluation using standard metrics demonstrates a rigorous methodology. The introduction of NER for extracting concepts from literature is intriguing, while the provision of a method for others to contribute to BERT model pre-training enhances collaborative research efforts. The innovative use of BERT models to contextualize archaeological data is a notable strength, bridging the gap between digitized information and computational models. Additionally, the paper's release of fine-tuned models and consideration of environmental implications add further value. In summary, the paper contributes significantly to the task of NER in archaeology, filling a crucial gap and providing foundational tools for data mining and reevaluating legacy archaeological materials and archives. Reference Brandsen, A. (2024). Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch. Zenodo, 8296920, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296920 | Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch | Alex Brandsen | <p>This short paper describes a collection of BERT models for the archaeology domain. We took existing language specific BERT models in English, German, and Dutch, and further pre-trained them with archaeology specific training data. We then took ... |  | Computational archaeology | Maria Pia di Buono | 2023-08-29 14:50:21 | View | |

19 Feb 2024

Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias ReductionFumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330Evaluating Methods for Reducing Sampling Bias in Network AnalysisRecommended by James Allison based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer

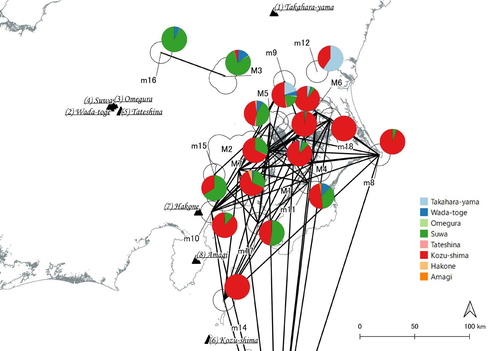

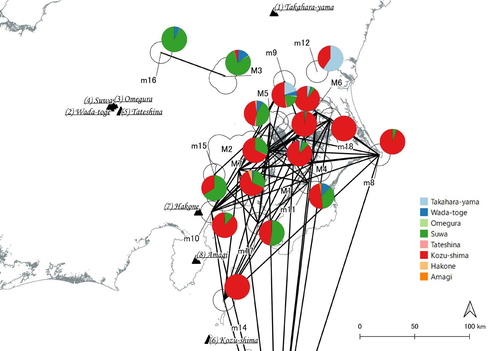

In a recent article, Fumihiro Sakahira and Hiro'omi Tsumura (2023) used social network analysis methods to analyze change in obsidian trade networks in Japan throughout the 13,000-year-long Jomon period. In the paper recommended here (Sakahira and Tsumura 2024), Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction they revisit that data and describe additional analyses that confirm the robustness of their social network analysis. The data, analysis methods, and substantive conclusions of the two papers overlap; what this new paper adds is a detailed examination of the data and methods, including use of bootstrap analysis to demonstrate the reasonableness of the methods they used to group sites into clusters. Both papers begin with a large dataset of approximately 21,000 artifacts from more than 250 sites dating to various times throughout the Jomon period. The number of sites and artifacts, varying sample sizes from the sites, as well as the length of the Jomon period, make interpretation of the data challenging. To help make the data easier to interpret and reduce problems with small sample sizes from some sites, the authors assign each site to one of five sub-periods, then define spatial clusters of sites within each period using the DBSCAN algorithm. Sites with at least three other sites within 10 km are joined into clusters, while sites that lack enough close neighbors are left as isolates. Clusters or isolated sites with sample sizes smaller than 30 were dropped, and the remaining sites and clusters became the nodes in the networks formed for each period, using cosine similarities of obsidian assemblages to define the strength of ties between clusters and sites. The main substantive result of Sakahira and Tsumura’s analysis is the demonstration that, during the Middle Jomon period (5500-4500 cal BP), clusters and isolated sites were much more connected than before or after that period. This is largely due to extensive distribution of obsidian from the Kozu-shima source, located on a small island off the Japanese mainland. Before the Middle Jomon period, Kozu-shima obsidian was mostly found at sites near the coast, but during the Middle Jomon, a trade network developed that took Kozu-shima obsidian far inland. This ended after the Middle Jomon period, and obsidian networks were less densely connected in the late and last Jomon periods. The methods and conclusions are all previously published (Sakahira and Tsumura 2023). What Sakahira and Tsumura add in Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction are: · an examination of the distribution of cosine similarities between their clusters for each period · a similar evaluation of the cosine similarities within each cluster (and among the unclustered sites) for each period · bootstrap analyses of the mean cosine similarities and network densities for each time period These additional analyses demonstrate that the methods used to cluster sites are reasonable, and that the use of spatially defined clusters as nodes (rather than the individual sites within the clusters) works well as a way of reducing bias from small, unrepresentative samples. An alternative way to reduce that bias would be to simply drop small assemblages, but that would mean ignoring data that could usefully contribute to the analysis. The cosine similarities between clusters show patterns that make sense given the results of the network analysis. The Middle Jomon period has, on average, the highest cosine similarities between clusters, and most cluster pairs have high cosine similarities, consistent with the densely connected, spatially expansive network from that time period. A few cluster pairs in the Middle Jomon have low similarities, apparently representing comparisons including one of the few nodes on the margins on the network that had little or no obsidian from the Kozu-shima source. The other four time periods all show lower average inter-cluster similarities and many cluster pairs have either high or low similarities. This probably reflects the tendency for nearby clusters to have very similar obsidian assemblages to each other and for geographically distant clusters to have dissimilar obsidian assemblages. The pattern is consistent with the less densely connected networks and regionalization shown in the network graphs. Thinking about this pattern makes me want to see a plot of the geographic distances between the clusters against the cosine similarities. There must be a very strong correlation, but it would be interesting to know whether there are any cluster pairs with similarities that deviate markedly from what would be predicted by their geographic separation. The similarities within clusters are also interesting. For each time period, almost every cluster has a higher average (mean and median) within-cluster similarity than the similarity for unclustered sites, with only two exceptions. This is partial validation of the method used for creating the spatial clusters; sites within the clusters are at least more similar to each other than unclustered sites are, suggesting that grouping them this way was reasonable. Although Sakahira and Tsumura say little about it, most clusters show quite a wide range of similarities between the site pairs they contain; average within-cluster similarities are relatively high, but many pairs of sites in most clusters appear to have low similarities (the individual values are not reported, but the pattern is clear in boxplots for the first four periods). There may be value in further exploring the occurrence of low site-to-site similarities within clusters. How often are they caused by small sample sizes? Clusters are retained in the analysis if they have a total of at least 30 artifacts, but clusters may contain sites with even smaller sample sizes, and small samples likely account for many of the low similarity values between sites in the same cluster. But is distance between sites in a cluster also a factor? If the most distant sites within a spatially extensive cluster are dissimilar, subdividing the cluster would likely improve the results. Further exploration of these within-cluster site-to-site similarity values might be worth doing, perhaps by plotting the similarities against the size of the smallest sample included in the comparison, as well as by plotting the cosine similarity against the distance between sites. Any low similarity values not attributable to small sample sizes or geographic distance would surely be worth investigating further. Sakahira and Tsumura also use a bootstrap analysis to simulate, for each time period, mean cosine similarities between clusters and between site pairs without clustering. They also simulate the network density for each time period before and after clustering. These analyses show that, almost always, mean simulated cosine similarities and mean simulated network density are higher after clustering than before. The simulated mean values also match the actual mean values better after clustering than before. This improved match to actual values when the sites are clustered for the bootstrap reinforces the argument that clustering the sites for the network analysis was a reasonable result. The strength of this paper is that Sakahira and Tsumura return to reevaluate their previously published work, which demonstrated strong patterns through time in the nature and extent of Jomon obsidian trade networks. In the current paper they present further analyses demonstrating that several of their methodological decisions were reasonable and their results are robust. The specific clusters formed with the DBSCAN algorithm may or may not be optimal (which would be unreasonable to expect), but the authors present analyses showing that using spatial clusters does improve their network analysis. Clustering reduces problems with small sample sizes from individual sites and simplifies the network graphs by reducing the number of nodes, which makes the results easier to interpret. Reference Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2023). Tipping Points of Ancient Japanese Jomon Trade Networks from Social Network Analyses of Obsidian Artifacts. Frontiers in Physics 10:1015870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.1015870 Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2024). Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction, Zenodo, 10057602, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330 | Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction | Fumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura | <p>This study aims to investigate the dynamics of obsidian trade networks during the Jomon period (approximately 15,000 to 2,400 years ago), the hunting and gathering era in Japan. To improve regional representation and reduce the distortions caus... |  | Asia, Computational archaeology | James Allison | Thegn Ladefoged, Matthew Peeples | 2023-05-28 05:51:12 | View |

14 Nov 2023

Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics ClassroomStephan, Robert https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8221286Learning with Archaeogaming? A study based on student feedbackRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Jeremiah McCall and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jeremiah McCall and 1 anonymous reviewer

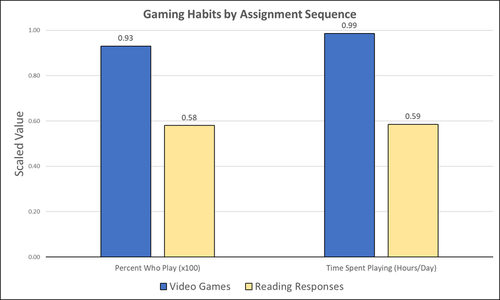

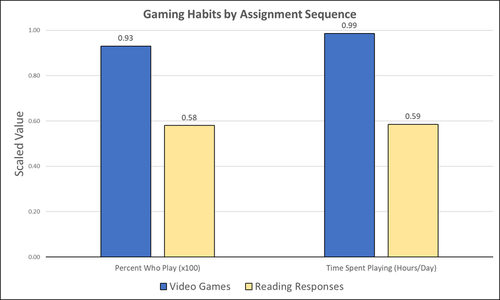

This paper (Stephan 2023) is about the use of video games as a pedagogical tool in class. Instead of taking the perspective of a lecturer, the author seeks the student’s perspectives to evaluate the success of an interactive teaching method at the crossroads of history, archaeology, and classics. The paper starts with a literature review, that highlights the intensive use of video games among college students and high schoolers as well as the impact video games can have on learning about the past. The case study this paper is based on is made with the game Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, which is introduced in the next part of the paper as well as previous works on the same game. The author then explains his method, which entailed the tasks students had to complete for a class in classics. They could either choose to play a video game or more classically read some texts. After the tasks were done, students filled out a 14-question-survey to collect data about prior gaming experience, assignment enjoyment, and other questions specific to the assignments. The results were based on only a fraction of the course participants (n=266) that completed the survey (n=26), which is a low number for doing statistical analysis. Besides some quantitative questions, students had also the possibility to freely give feedback on the assignments. Both survey types (quantitative answers and qualitative feedback) solely relied on the self-assessment of the students and one might wonder how representative a self-assessment is for evaluating learning outcomes. Both problems (size of the survey and actual achievements of learning outcomes) are getting discussed at the end of the paper, that rightly refers to its results as preliminary. I nevertheless think that this survey can help to better understand the role that video games can play in class. As the author rightly claims, this survey needs to be enhanced with a higher number of participants and a better way of determining the learning outcomes objectively. This paper can serve as a start into how we can determine the senseful use of video games in classrooms and what students think about doing so. References

Stephan, R. (2023). Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics Classroom, Zenodo, 8221286, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8221286

| Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics Classroom | Stephan, Robert | <p>This study assesses student feedback from the implementation of Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey as a teaching tool in a lower level, general education Classics course (CLAS 160B1 - Meet the Ancients: Gateway to Greece and Rome). In this course, which... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Mediterranean | Sebastian Hageneuer | Anonymous, Jeremiah McCall | 2023-08-07 16:45:31 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer