Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

21 Nov 2022

Removing Barriers to Reproducible Research in ArchaeologyEmma Karoune and Esther Plomp https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7320029Three levels of reproducible workflow remove barriers for archaeologists and increase accessibilityRecommended by Ben Marwick based on reviews by Sam Leggett, Cyler Conrad, Cheng Liu and Lisa Lodwick based on reviews by Sam Leggett, Cyler Conrad, Cheng Liu and Lisa Lodwick

Over the last decade, a small but growing community of archaeologists, from a diversity of intellectual and demographic backgrounds, have been striving for computational reproducibility in their published research. In their survey of the accomplishments of this thriving community, Emma Karoune and Esther Plomp (2022) analyzed the wide variety of approaches researchers have taken to enhance the reproducibility of their research. A key contribution of this paper is their excellent synthesis of diverse approaches into three levels of increasing complexity. This is helpful because it provides multiple entry points for researchers new to the challenge of fortifying their research. Many researchers assume that computational reproducibility is only achievable if they have a high degree of technical skill with computers, or is only necessary if their work is very computationally intensive. Karoune and Plomp give three compelling reasons why reproducibility is important for all archaeological research, and through their three levels they demonstrate that how these levels can be accomplished with basic, non-specialized computer skills and widely used free software. They showcase exemplary work from a variety of archaeologists to show how practical and achievable reproducible research is for all archaeologists. They advocate for archaeologists to use the most widely used and supported tools and services to support their reproducible research, such as the R and Python programming languages for data analysis, and Git and GitHub for collaboration. This paper, with its extensive appendix including thoughtful responses to frequently asked questions about reproducible research in archaeology, is likely to have a wide reach and influence, beyond previous works on this topic that have largely focused on technical details. Karoune and Plomp have provided the on-ramp for a generation of archaeologists who will find their questions about reproducible research answered here. They will also find an agreeable entry point to reproducible research in one of the three levels described by the authors. Will every archaeologist embrace this way of working? Should they? The work of Leonelli (2018) can help us anticipate the answers to these questions. Leonelli asks where are the limits to reproducibility, and how do the characteristics of different ways of knowing affect the desirability of reproducibility? Leonelli's work invites us to consider that there will be archaeologists coming from different epistemic cultures for whom the motivations presented by Karoune and Plomp will not resonate. For example, archaeologists engaged in mostly hermeneutical social science and humanities research, who do little or no quantitative analysis and statistics, are unlikely to see reproducibility as meaningful or desirable for their work. We can describe these researchers as working in interpretative or constructivist epistemic cultures. In these cultures, the particulars of how an individual researcher engages with their subject are exclusive and unique, and they would argue it cannot be fully captured or shared in an meaningful way (Elman and Kapiszewski 2017). Here, knowledge is situational, emerging from a specific, once-off combination of people and circumstances. One example in archaeology is the chaîne opératoire approach of stone artefact analysis, which Monnier and Missal (2014:61) describe as "based upon the analyst's experience and intuition, and it is not replicable, nor quantifiable". To make sense of this example we can draw on Galison's (1997) concept of 'image traditions' and 'logic traditions'. An image tradition is a way of knowing that is qualitative, based on composing narratives from drawings and photographs. A logic tradition is based on the use of instruments and statistical methods to collect standardised quantitative data. Chaîne opératoire approaches fall into the image tradition, along with many other ways of working in archaeology that do not generate numbers or use them to support claims about the past. Archaeologists working in a logic tradition will find reproducible research to be more meaningful than those working in an image tradition. We should be mindful not to claim that one epistemic culture is superior to another because reproducibility is not meaningful or attainable for researchers in one culture. Such a claim would threaten the plurality that is essential for the reliability of scientific knowledge (Massimi 2022). Instead we should identify those communities in archaeology where reproducible research is both meaningful and attainable, but has not yet been widely embraced. That is the where the most beneficial effects can be expected. According to Leonelli's (2018) framework, we can recognise these communities by a few basic characteristics. For example: they are doing computationally intensive archaeology, such as using or writing software to collect, simulate, analyse or visualise data; they are doing experimental archaeology; or they are making knowledge claims that are supported by tables of numeric data and data visualisations. Archaeologists whose work shares one or more of these characteristics will find the guidance provided here by Karoune and Plomp to be highly instructive and relevant, and stand the most to benefit from it. But it is not only individual archaeological scientists that have potential to benefit from how Karoune and Plomp have lowered the barriers to reproducible research. An especially important implication of this paper is that by lowering the barriers to reproducible research, Karoune and Plomp help us all to lower barriers to participation in archaeology in general. Documenting our research transparently, and sharing our materials (such as data and code and so on) openly, can profoundly change how others can participate in archaeology. By doing this, we are enabling students and researchers elsewhere, for example in low and middle income locations, to use our materials in their teaching and learning. Other researchers and students can apply our methods to their data, and combine their data with ours to achieve syntheses beyond what a single project can do. Similarly, for archaeologists working with local, descendant or marginalized communities, the tools of reproducible research are vital for enabling community members to have full access to the archaeological process, and thus reproducibility may be considered a necessity for decolonising the discipline. Karoune and Plomp present the CARE principles (Carroll et al. 2020) to guide archaeologists in ensuring community control of data so that reproducibility can be ethically accomplished with community safety and well-being as a priority. This may have a profoundly positive impact on the demographics of archaeology, as it lowers the barriers of meaningful participation by people far beyond our immediate groups of collaborators. Making archaeology more accessible is of critical importance in stemming the negative social impacts of pseudoarchaeologists, who often claim that archaeologists actively suppress the truth of the archaeological record through secrecy, elitism, and exclusiveness. The harm in this is twofold. First, that pseudoarchaeology typically erases Indigenous heritage by claiming that their past achievements were due to an ancient, extinct advanced civilization, not Indigenous people. These claims are often adopted by white supremacists to support racist and antisemitic conspiracy theories (Turner and Turner 2021), which sometimes leads to prejudice, physical violence, radicalization and extremism. A second type of harm that can come from claims of secrecy and elitism is it drains public trust in experts, leading to science denial. Not only trust in archaeologists, but trust in many kinds of experts, including those working on urgent contemporary issues such as public health and climate change. Karoune and Plomp's work is important here because it provides a practical and affordable pathway for archaeologists to fight claims of secrecy and elitism by sharing their work in ways that make it possible for non-academics to inspect the analyses and logic in detail. Claims of secrecy and elitism can be easily countered by openness, transparently and reproducibility by archaeologists. This is not only useful for tackling pseudoarchaeologists, but also in enacting an ethic of care, framing members of the public as people that not only care about archaeology as part of humanity's shared heritage, but also care for the construction of reliable interpretations of the archaeological record to provide secure and authentic foundations for their social identities and relationships (Wylie et al 2018; de la Bellacasa 2011). By striving for reproducible research in the way described by Karoune and Plomp, we are practicing a kind of reciprocal care among ourselves as archaeologists, and between archaeologists and members of the public as two communities who care about the human past.

References Karoune, E., and Plomp, E. (2022). Removing Barriers to Reproducible Research in Archaeology. Zenodo, 7320029, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7320029 de la Bellacasa, M. P. (2011). Matters of care in technoscience: Assembling neglected things. Social Studies of Science, 41(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312710380301 Carroll, S. R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O. L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R., Sara, R., Walker, J. D., Anderson, J., and Hudson, M. (2020). The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Science Journal, 19(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-043 Elman, C., and Kapiszewski, D. (2017). Benefits and Challenges of Making Qualitative Research More Transparent. Inside Higher Ed 2017, http://web.archive.org/web/20220407064134/https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/rethinking-research/benefits-and-challenges-making-qualitative-research-more-transparent (accessed 21 Oct, 2022). Galison, P. (1997). Image and logic: a material culture of microphysics. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago Press. Leonelli, S. (2018). Re-Thinking Reproducibility as a Criterion for Research Quality [preprint]. Available online: http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/id/eprint/14352 (Accessed 21 Oct 2022). Massimi, M. (2022). Perspectival realism. Oxford University Press. Monnier, G. F., and Kele M.. "Another Mousterian debate? Bordian facies, chaîne opératoire technocomplexes, and patterns of lithic variability in the western European Middle and Upper Pleistocene." Quaternary International 350 (2014): 59-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2014.06.053 Turner, D. D., and Turner, M. I. (2021). “I’m Not Saying It Was Aliens”: An Archaeological and Philosophical Analysis of a Conspiracy Theory. In A. Killin and S. Allen-Hermanson (Eds.), Explorations in Archaeology and Philosophy (pp. 7–24). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61052-4_2 Wylie, C., Neeley, K., and Ferguson, S. (2018). Beyond Technological Literacy: Open Data as Active Democratic Engagement? Digital Culture & Society, 4(2), 157–182. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2018-0209

| Removing Barriers to Reproducible Research in Archaeology | Emma Karoune and Esther Plomp | <p>Reproducible research is being implemented at different speeds in different disciplines, and Archaeology is at the start of this journey. Reproducibility is the practice of reanalysing data by taking the same steps and producing the same or sim... |  | Computational archaeology | Ben Marwick | 2022-06-07 10:02:46 | View | |

08 Feb 2021

A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, ChinaLuc Doyon, Zhanyang Li, Hua Wang, Lila Geis, Francesco d’Errico https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/68xpzA step towards the challenging recognition of expedient bone toolsRecommended by Camille Daujeard based on reviews by Delphine Vettese, Jarod Hutson and 1 anonymous reviewerThis article by L. Doyon et al. [1] represents an important step to the recognition of bone expedient tools within archaeological faunal assemblages, and therefore deserves publication. In this work, the authors compare bone flakes and splinters experimentally obtained by percussion (hammerstone and anvil technique) with fossil ones coming from the Palaeolithic site of Lingjing in China. Their aim is to find some particularities to help distinguish the fossil bone fragments which were intentionally shaped, from others that result notably from marrow extraction. The presence of numerous (>6) contiguous flake scars and of a continuous size gradient between the lithics and the bone blanks used, appear to be two valuable criteria for identifying 56 bone elements of Lingjing as expedient bone tools. The latter are present alongside other bone tools used as retouchers [2]. Another important point underlined by this study is the co-occurrence of impact and flake scars among the experimentally broken specimens (~90%), while this association is seldom observed on archaeological ones. Thus, according to the authors, a low percentage of that co-occurrence could be also considered as a good indicator of the presence of intentionally shaped bone blanks. About the function of these expedient bone tools, the authors hypothesize that they were used for in situ butchering activities. However, future experimental investigations on this question of the function of these tools are expected, including an experimental use wear program. Finally, highlighting the presence of such a bone industry is of importance for a better understanding of the adaptive capacities and cultural practices of the past hominins. This work therefore invites all taphonomists to pay more attention to flake removal scars on bone elements, keeping in mind the possible existence of that type of bone tools. In fact, being able to distinguish between bone fragments due to marrow recovery and bone tools is still a persistent and important issue for all of us, but one that deserves great caution. [1] Doyon, L., Li, Z., Wang, H., Geis, L. and d'Errico, F. 2021. A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, China. Socarxiv, 68xpz, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/68xpz [2] Doyon, L., Li, Z., Li, H., and d’Errico, F. 2018. Discovery of circa 115,000-year-old bone retouchers at Lingjing, Henan, China. Plos one, 13(3), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194318. | A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, China | Luc Doyon, Zhanyang Li, Hua Wang, Lila Geis, Francesco d’Errico | <p>Activities attested since at least 2.6 Myr, such as stone knapping, marrow extraction, and woodworking may have allowed early hominins to recognize the technological potential of discarded skeletal remains and equipped them with a transferable ... |  | Asia, Middle Palaeolithic, Osseous industry, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Camille Daujeard | 2020-11-01 11:09:13 | View | |

04 Jul 2024

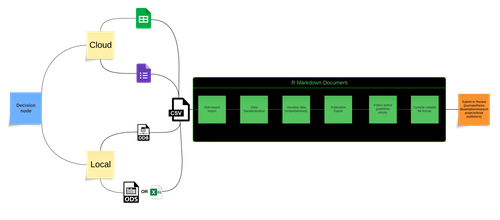

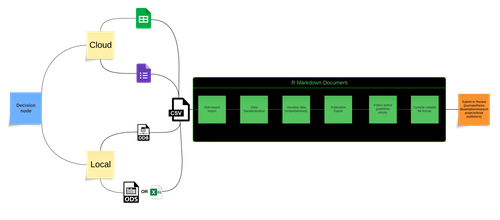

An approach to establishing a workflow pipeline for synergistic analysis of osteological and biochemical data. The case study of Amvrakia in the context of Corinthian colonisation between 625-189 BC in Epirus, Greece.Kiriakos Xanthopoulos, Angeliki Georgiadou, Christina Papageorgopoulou https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298579Establishing a workflow for recording and analysing bioarchaeological dataRecommended by Christianne Fernee based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper by Xanthopoulos and colleagues [1] presents an approach to establish a pipeline for the analysis of osteological and biochemical data. This approach integrates novel data collection, FAIR principles for data longevity and accessibility, utilises R markdown and cloud webware. Following the changes recommended by the reviewers this paper presents a welcome contribution to osteoarcheology and bioarchaeology. Osteoarchaeology and bioarchaeology often involves the collection of vast amounts of data both in the field and from consequential analysis in the lab. From this data we can reconstruct many aspects of past human experiences. However, issues often arise when bringing together these diverse types of data. In this regard, this paper proposes are useful methodology in which osteoarchaeological researchers can bring their data together as part of a streamlined process, from data collection to analyses.

References [1] Xanthopoulos, K., Georgiadou, A. and Papageorgopoulou, C. (2024). An approach to establishing a workflow pipeline for synergistic analysis of osteological and biochemical data. The case study of Amvrakia in the context of Corinthian colonisation between 625-189 BC in Epirus, Greece. Zenodo, 11156506, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298579 | An approach to establishing a workflow pipeline for synergistic analysis of osteological and biochemical data. The case study of Amvrakia in the context of Corinthian colonisation between 625-189 BC in Epirus, Greece. | Kiriakos Xanthopoulos, Angeliki Georgiadou, Christina Papageorgopoulou | <p>Bioarchaeology has long focused on understanding past human life through skeletal remains, including oral pathology and stable isotope analysis. Despite advancements in statistical analysis, correlations are still largely made manually. To stre... |  | Antiquity, Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Conservation/Museum studies, Mediterranean, Physical anthropology | Christianne Fernee | 2023-08-30 14:01:44 | View | |

02 May 2023

Transmission of lithic and ceramic technical know-how in the Early Neolithic of central-western Europe: Shedding Light on the Social Mechanisms underlying Cultural TransitionSolène Denis, Louise Gomart, Laurence Burnez-Lanotte, Pierre Allard https://osf.io/gqnht/A Thought Provoking Consideration of Craft in the NeolithicRecommended by Clare Burke based on reviews by Bogdana Milić and 1 anonymous reviewerThe pioneering work of Leroi-Gourhan introduced archaeologists to the concept of the chaîne opératoire[1], whereby, like his supervisor Mauss[2], Leroi-Gourhan proposed direct links between bodily actions and aspects of cultural identity. The chaîne opératoire offers a powerful conceptual tool with which to reconstruct and describe the technological practices undertaken by craftspeople, linking material objects to the cultural context in which crafts are learnt. Although initially applied to lithics, the concept today is well known in ceramic studies, as well as, other material crafts, in order to identify aspects of tradition and identity through ideas linked to technological style[3,4] and communities of practice[5]. Utilizing this approach, Denis et al.[6] use the chaîne opératoire to look at both lithics and ceramics together from a diachronic viewpoint, to examine technical systems present over the transition between Linearbandkeramic (LBK) and post LBK Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint German (BQY/VSG) timeframes. This much needed comparative and diachronic perspective, focuses on material from the sites of Vaux-et-Borset and Verlaine in Belgium, and has enabled the authors to consider the impact of changing social dynamics on these two crafts simultaneously. The authors examine the ceramic and lithic assemblages from a macroscopic and morphological perspective in order to identify techniques of production. The data gathered testifies to the dominance of one production technique for each craft within the LBK. There is particularly striking homogeneity noted for the lithics that suggests the transmission of a single tradition over the Hesbaye area, whilst the ceramics display greater regional diversity. The picture alters somewhat for the BQY/VSG material where it seems there is an increase in the diversity of production techniques, with both the introduction of new techniques, as well as a degree of hybridization of earlier techniques to form new BQY/VSG chaînes opératoires that have LBK roots. The BQY/VSG diversity noted for the lithics is especially interesting, with the introduction of techniques that attest to increased expertise which the authors attest to the migration of an external group. The results of this work have allowed Denis et al. to discuss multiple influences on the technical systems they identify. Rather than trying to fit the data within a single model, the authors demonstrate the need for nuance, considering the social changes associated with Neolithic migration and interactions, as multifaced and dynamic. As such, they are able to show not only the influence of contact with other groups, but that the apparent migration of external groups does not simply lead to the replacement of the crafting heritage already established at the sites they have examined. In concluding the authors acknowledge, that as scholars push the existing state of knowledge (in this respect analysis of raw materials would make an especially important contribution), the picture presented in the paper may alter. Future work will hopefully fill in current gaps, particularly in terms of how far the trends identified extend, and the extent to which the lithic and ceramic pictures diversify on a broader geographical scale. It is certain that based on such results, future work should adopt the comparative approach presented by the authors, who have demonstrated its explanatory potential for understanding the technical and cultural groups we all study. [2] Mauss, M. 2009 [1934]. Techniques, Technology and Civilisation. Edited and introduced by N. Schlanger. New York/Oxford: Durkheim Press/Berghahn Books. [3] Lechtman, H. 1977. Style in Technology: some early thoughts. In H. Lechtman and R.S. Merrill (eds.) Material Culture: styles, organization and dynamics of technology. Proceedings of the American Ethnological Society 1975, St. Paul, 3-20. [4] Gosselain, O. 1992. Technology and Style: Potters and Pottery Among Bafia of Cameroon. Man 27(3) 559- 586. htpps://doi.org/10.2307/2803929. [5] Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [6] Denis, S., Gomart, L., Burnez-Lanotte, L. and Allard, P. (2023). Transmission of lithic and ceramic technical know-how in the Early Neolithic of central-western Europe: Shedding Light on the Social Mechanisms underlying Cultural Transition. OSF Preprints, gqnht, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/gqnht

| Transmission of lithic and ceramic technical know-how in the Early Neolithic of central-western Europe: Shedding Light on the Social Mechanisms underlying Cultural Transition | Solène Denis, Louise Gomart, Laurence Burnez-Lanotte, Pierre Allard | <p>Research on the European Neolithisation agrees that a process of colonisation throughout the sixth millennium BC underlies the spread of agricultural ways of life on the continent. From central to central-western Europe, this colonisation path ... |  | Ceramics, Europe, Lithic technology, Neolithic | Clare Burke | 2022-11-18 12:03:55 | View | |

14 Mar 2024

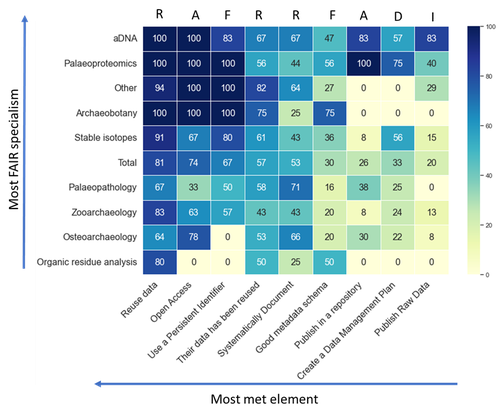

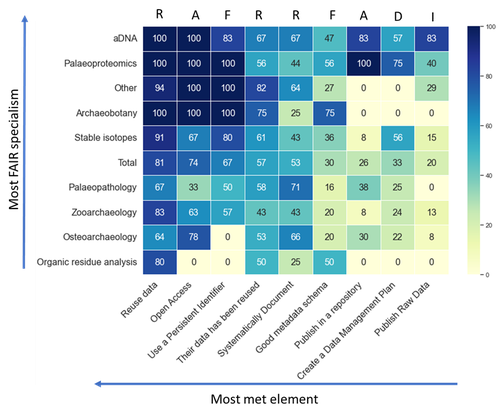

How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data ReusableLien-Talks, Alphaeus https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910FAIR data in bioarchaeology - where are we at?Recommended by Claudia Speciale based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers

The increasing reliance on digital and big data in archaeology is pushing the scientific community more and more to reconsider their storing and use [1, 2]. Furthermore, the openness and findability in the way these data are shared represent a key matter for the growth of the discipline, especially in the case of bioarchaeology and archaeological sciences [3]. In this paper, [4] the author presents the result of a survey targeted on UK bioarchaeologists and then extended worldwide. The paper maintains the structure of a report as it was intended for the conference it was part of (CAA 2023, Amsterdam) but it represents the first public outcome of an inquiry on the bioarchaeological scientific community. A reflection on ourselves and our own practices. Are all the disciplines adhering to the same policies? Do any bioarchaeologist use the same protocols and formats? Are there any differences in between the domains? Is the Needs Analysis fulfilling the questions? The results, obtained through an accurate screening to avoid distortions, are creating an intriguing picture on the current state of "fairness" and highlighting how Institutions' rules and policies can and should indicate the correct workflow to follow. In the end, the wide application of the FAIR principles will contribute significantly to the growth of the disciplines and to create an environment where the users are not just contributors, but primary beneficiaries of the system. [1] Huggett j. (2020). Is Big Digital Data Different? Towards a New Archaeological Paradigm, Journal of Field Archaeology, 45:sup1, S8-S17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2020.1713281 [2] Nicholson C., Kansa S., Gupta N. and Fernandez R. (2023). Will It Ever Be FAIR?: Making Archaeological Data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Advances in Archaeological Practice 11 (1): 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2022.40 [3] Plomp E., Stantis C., James H.F., Cheung C., Snoeck C., Kootker L., Kharobi A., Borges C., Reynaga D.K.M., Pospieszny Ł., Fulminante, F., Stevens, R., Alaica, A. K., Becker, A., de Rochefort, X. and Salesse, K. (2022). The IsoArcH initiative: Working towards an open and collaborative isotope data culture in bioarchaeology. Data in brief, 45, p.108595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2022.108595 [4] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable. Zenodo, 8139910, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910 | How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable | Lien-Talks, Alphaeus | <p>Bioarchaeology, which encompasses the study of ancient DNA, osteoarchaeology, paleopathology, palaeoproteomics, stable isotopes, and zooarchaeology, is generating an ever-increasing volume of data as a result of advancements in molecular biolog... |  | Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Zooarchaeology | Claudia Speciale | 2023-07-12 19:12:44 | View | |

02 May 2024

Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the MuseumAntonis G. Dimitriou, Stella Papadopoulou, Maria Dermenoudi, Angeliki Moneda, Vasiliki Drakaki, Andreana Malama, Alexandros Filotheou, Aristidis Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, Anastasios Tzitzis, Spyros Megalou, Stavroula Siachalou, Aggelos Bletsas, Traianos Yioultsis, Anna Maria Velentza, Sofia Pliasa, Nikolaos Fachantidis, Evangelia Tsangaraki, Dimitrios Karolidis, Charalampos Tsoungaris, Panagiota Balafa and Angeliki Koukouvou https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7805387Social Robotics in the Museum: a case for human-robot interaction using RFID TechnologyRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and Alexis PantosThe paper “Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum” (Dimitriou et al 2023) is a relevant contribution to museology and an interface between the public, archaeological discourse and the field of social robotics. It deals well with these themes and is concise in its approach, with a strong visual component that helps the reader to understand what is at stake. The option of demonstrating the different steps that lead to the final construction of the robot is appropriate, so that it is understood that it really is a linked process and not simple tasks that have no connection. The use of RFID technology for topological movement of social robots has been continuously developed (e.g., Corrales and Salichs 2009; Turcu and Turcu 2012; Sequeira and Gameiro 2017) and shown to have advantages for these environments. Especially in the context of a museum, with all the necessary precautions to avoid breaching the public's privacy, RFID labels are a viable, low-cost solution, as the authors point out (Dimitriou et al 2023), and, above all, one that does not require the identification of users. It is in itself part of an ambitious project, since the robot performs several functions and not just one, a development compared to other currents within social robotics (see Hellou et al 2022: 1770 for a description of the tasks given to robots in museums). The robotic system itself also makes effective use of the localization system, both physically, by RFID labels and by knowing how to situate itself with the public visiting the museum, adapting to their needs, which is essential for it to be successful (see Gasteiger, Hellou and Ahn 2022: 690 for the theme of localization). Archaeology can provide a threshold of approaches when it comes to social robotics and this project demonstrates that, bringing together elements of interaction, education and mobility in a single method. Hence, this is a paper with great merit and deserves to be recommended as it allows us to think of the museum as a space where humans and non-humans can converge to create intelligible discourses, whether in the historical, archaeological or cultural spheres. References Dimitriou, A. G., Papadopoulou, S., Dermenoudi, M., Moneda, A., Drakaki, V., Malama, A., Filotheou, A., Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, A., Tzitzis, A., Megalou, S., Siachalou, S., Bletsas, A., Yioultsis, T., Velentza, A. M., Pliasa, S., Fachantidis, N., Tsagkaraki, E., Karolidis, D., Tsoungaris, C., Balafa, P. and Koukouvou, A. (2024). Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum. Zenodo, 7805387, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7805387 Corrales, A. and Salichs, M.A. (2009). Integration of a RFID System in a Social Robot. In: Kim, JH., et al. Progress in Robotics. FIRA 2009. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 44. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03986-7_8 Gasteiger, N., Hellou, M. and Ahn, H.S. (2023). Factors for Personalization and Localization to Optimize Human–Robot Interaction: A Literature Review. Int J of Soc Robotics 15, 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-021-00811-8 Hellou, M., Lim, J., Gasteiger, N., Jang, M. and Ahn, H. (2022). Technical Methods for Social Robots in Museum Settings: An Overview of the Literature. Int J of Soc Robotics 14, 1767–1786 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-022-00904-y Sequeira, J. S., and Gameiro, D. (2017). A Probabilistic Approach to RFID-Based Localization for Human-Robot Interaction in Social Robotics. Electronics, 6(2), 32. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/electronics6020032 Turcu, C. and Turcu, C. (2012). The Social Internet of Things and the RFID-based robots. In: IV International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2012, pp. 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUMT.2012.6459769 | Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum | Antonis G. Dimitriou, Stella Papadopoulou, Maria Dermenoudi, Angeliki Moneda, Vasiliki Drakaki, Andreana Malama, Alexandros Filotheou, Aristidis Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, Anastasios Tzitzis, Spyros Megalou, Stavroula Siachalou, Aggelos Bletsas, ... | <p>This paper summarizes the adoption of new technologies in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece. RFID technology has been adopted. RFID tags have been attached to the artifacts. This allows for several interactions, including tracki... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Remote sensing | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-04-10 14:04:23 | View | |

29 Jan 2024

Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept researchJ.Y Blaise, I.Dudek, L.Bergerot, G.Simon https://zenodo.org/record/79831633D Models, Knowledge and Visualization: a prototype for 3D virtual models according to plausible criteriaRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Robert Bischoff and Louise TharandtThe construction of 3D realities is deeply embedded in archaeological practices. From sites to artifacts, archaeology has dedicated itself to creating digital copies for the most varied purposes. The paper “Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's 3 scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research” (Jean-Yves et al 2024) represents an advance, in the sense that it does not just deal with a three-dimensional theory for archaeological practice, but rather offers proposals regarding the epistemic component, how it is possible to represent knowledge through the workflow of 3D virtual reconstructions themselves. The authors aim to unite three main axes - knowledge modeling, visual encoding and 3D content reuse - (Jean-Yves et al 2024: 2), which, for all intents and purposes, form the basis of this article. With regard to the first aspect, this work questions how it is possible to transmit the knowledge we want to a 3D model and how we can optimize this epistemic component. A methodology based on plausibility criteria is offered, which, for the archaeological field, offers relevant space for reflection. Given our inability to fully understand the object or site that is the subject of the 3D representation, whether in space or time, building a method based on probabilistic categories is probably one of the most realistic approaches to the realities of the past. Thus, establishing a plausibility criterion allows the user to question the knowledge that is transmitted through the representation, and can corroborate or refute it in future situations. This is because the role of reusing these models is of great interest to the authors, a perfectly justifiable sentiment, as it encourages a critical view of scientific practices. Visual encoding is, in terms of its conjunction with knowledge practices, a key element. The notion of simplicity under Maeda's (2006) design principles not only represents a way of thinking that favors operability, but also a user-friendly design in the prototype that the authors have created. This is also visible when it comes to the reuse of parts of the models, in a chronological logic: adapting the models based on architectural elements that can be removed or molded is a testament to intelligent design, whereby instead of redoing models in their entirety, they are partially used for other purposes. All these factors come together in the final prototype, a web application that combines relational databases (RDBMS) with a data mapper (MassiveJS), using the PHP programming language. The example used is the Marmoutier Abbey hostelry, a centuries-old building which, according to the sources presented, has evolved architecturally over several centuries ((Jean-Yves et al 2024: 8). These states of the building are represented visually through architectural elements based on their existence, location, shape and size, always in terms of what is presented as being plausible. This allows not only the creation of a matrix in which various categories are related to various architectural elements, but also a visual aid, through a chromatic spectrum, of the plausibility that the authors are aiming for. In short, this is an article that seeks to rethink the degree of knowledge we can obtain through 3D visualizations and that does not take models as static, but rather realities that must be explored, recycled and reinterpreted in the light of different data, users and future research. For this reason, it is a work of great relevance to theoretical advances in 3D modeling adapted to archaeology.

References Blaise, J.-Y., Dudek, I., Bergerot, L. and Gaël, S. (2024). Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research, Zenodo, 7983163, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10496540 John Maeda. (2006). The Laws of Simplicity. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. | Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research | J.Y Blaise, I.Dudek, L.Bergerot, G.Simon | <p> 3D virtual reconstructions have become over the last decades a classical mean to communicate about analysts’ visions concerning past stages of development of an edifice or a site. However, they still today remain quite often a one-s... |  | Computational archaeology, Spatial analysis | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-05-30 00:43:03 | View | |

02 Jan 2024

Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenariosDiamanti, Eleni; Yip, Mauhing; Stahl, Annette; Ødegård, Øyvind https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305098Beyond Deep Blue: Underwater robotics, simulations and archaeologyRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Marco Moderato and 1 anonymous reviewerDiamanti et al. (2024) is a significant contribution to the field of underwater robotics and their use in archaeology, with an innovative approach to some major problems in the deployment of said technologies. It identifies issues when it comes to approaching Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) sites and does so through an interest in the combination of data, maneuverability, and the interpretation provided by the instruments that archaeologists operate. The article's motives are clear: it is not enough to find the means to reach these sites, but rather is fundamental to take a step forward in methodology and how we can safeguard certain aspects of data recovery with robust mission planning. To this end, the article does not fail to highlight previous contributions, in an intertwined web of references that demonstrate the marked evolution of the use of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), Remote Operated Vehicles (ROVs), Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Autonomous Surface Vehicles (ASVs), which are growing exponentially in use (see Kapetanović et al. 2020). It should be emphasized that the notion of ‘aquatic environment’ used here is quite broad and is not limited to oceanic or maritime environments, which allows for a larger perspective on distinct technologies that proliferate in underwater archaeology. There is also a relevant discussion on the typologies of sensors and how these autonomous vehicles obtain their data, where are debated Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) and LiDAR systems. Thus, the authors of this article propose the creation of a model that acquires data through simulations, which allows for a better understanding of what a real mission presupposes in the field. Their tripartite method - pre-mission planning; mission plan and post-mission plan - offers a performing algorithm that simplifies and provides reliability to all the parts of the intervention. The use of real cases to create simulation models allows for a substantial approximation to common practice in underwater environments. And yet, the article is at its most innovative status when it combines all the elements it sets out to explore. It could simply focus on the methodological or planning component, on obtaining data, or on theoretical problems. But it goes further, which makes this approach more complete and of interest to the archaeological community. By not taking any part as isolated, the problems and possible solutions arising from the course of the mission are carried over from one parameter to another, where details are worked upon and efficiency goals are set. One of the most significant cases is the tuning of ocean optics in aquatic environments according to the idiosyncracies of real cases (Diamanti et al. 2024: 8), a complex endeavor but absolutely necessary in order to increase the informative potential of the simulation. The exploration of various data capture models is also welcome, for the purposes of comparison and adaptation on a case-by-case basis. The brief theoretical reflection offered at the end of the article dwells in all these points and problematizes the difference between terrestrial and aquatic archaeology. In fact, the distinction does not only exist in the technical component, as although it draws in theoretical elements from archaeology that is carried out on land (see Krieger 2012 for this matter), the problems and interpretations are shaped by different factors and therefore become unique (Diamanti et al 2024: 15). The future, according to the authors, lies in increasing the autonomy of these vehicles so that the human element does not have to make decisions in a systematic way. It is in that note, and in order for that path to become closer to reality, that we strongly recommend this article for publication, in conjunction with the comments of the reviewers. We hope that its integrated approach, which brings together methods, theories and reflections, can become a broader modus operandi within the field of underwater robotics applied to archaeology. References: Diamanti, E., Yip, M., Stahl, A. and Ødegård, Ø. (2024). Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenarios, Zenodo, 8305098, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305098 Kapetanović, N., Vasilijević, A., Nađ, Đ., Zubčić, K., and Mišković, N. (2020). Marine Robots Mapping the Present and the Past: Unraveling the Secrets of the Deep. Remote Sensing, 12(23), 3902. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/rs12233902 Krieger, W. H. (2012). Theory, Locality, and Methodology in Archaeology: Just Add Water? HOPOS: The Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science, 2(2), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1086/666956

| Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenarios | Diamanti, Eleni; Yip, Mauhing; Stahl, Annette; Ødegård, Øyvind | <p>This paper presents a novel method for visual-based 3D mapping of underwater cultural heritage sites through marine robotic operations. The proposed methodology addresses the three main stages of an underwater robotic mission, specifically the ... | Computational archaeology, Remote sensing | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-08-31 16:03:10 | View | ||

24 Jan 2024

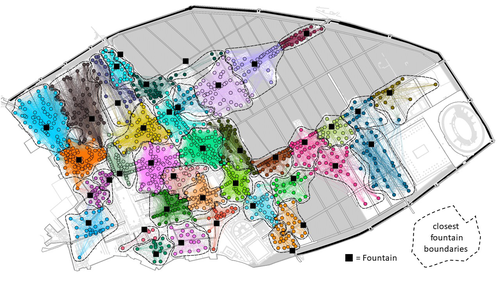

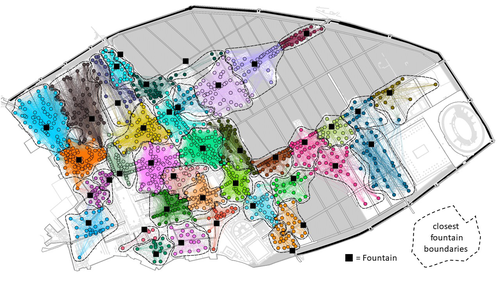

Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in PompeiiNotarian, Matthew https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305968A Valuable Contribution to Archaeological Network Research: A Case Study of PompeiiRecommended by David Laguna-Palma based on reviews by Matthew Peeples, Isaac Ullah and Philip Verhagen based on reviews by Matthew Peeples, Isaac Ullah and Philip Verhagen

The paper entitled 'Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii' [1] presents a significant contribution to the field of archaeological network research, particularly in the challenging task of identifying urban neighborhoods within the context of Pompeii. This study focuses on the relational dynamics within urban neighborhoods and examines their indistinct boundaries through advanced analytical methods. The methodology employed provides a comprehensive analysis of community detection, including the Louvain and Leiden algorithms, and introduces a novel Convex Hull of Admissible Modularity Partitions (CHAMP) algorithm. The incorporation of a network approach into this domain is both innovative and timely. The potential impact of this research is substantial, offering new perspectives and analytical tools. This opens new avenues for understanding social structures in ancient urban settings, which can be applied to other archaeological contexts beyond Pompeii. Moreover, the manuscript is not only methodologically solid but also well-written and structured, making complex concepts accessible to a broad audience. In conclusion, this study represents a valuable contribution to the field of archaeology, particularly for archaeological network research. Their results not only enhance our knowledge of Pompeii but also provide a robust framework for future studies in similar historical contexts. Therefore, this publication advances our understanding of social dynamics in historical urban environments. The rigorous analysis, combined with the innovative application of network algorithms, makes this study a noteworthy addition to the existing body of network science literature. It is recommended for a wide range of scholars interested in the intersection of archaeology, history, and network science. Reference [1] Notarian, Matthew. 2024. Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305968 | Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii | Notarian, Matthew | <p>The definition and identification of urban neighbourhoods in archaeological contexts remain complex and problematic, both theoretically and empirically. As constructs with both social and spatial characteristics, their detection through materia... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Computational archaeology, Mediterranean | David Laguna-Palma | 2023-08-31 19:28:35 | View | |

20 Feb 2024

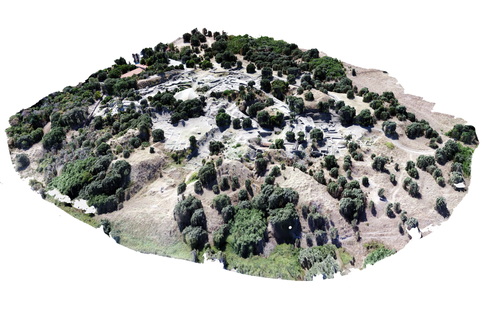

Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of ArchaeologyWaagen, Jitte & Wijngaarden, Gert Jan van https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10061343Rewriting Archaeological Narratives: Archaeology of Archaeology through 3D Site Topography RecordingRecommended by Devi Taelman based on reviews by Geert Verhoeven, Jesús García-Sánchez and Catherine Scott based on reviews by Geert Verhoeven, Jesús García-Sánchez and Catherine Scott

Even though applications of 3D recording have existed in archaeology for a long time, it is only since the early 2000s that this field of research has become mainstream thanks to technological advances, and the availability of low-cost sensors and image-based modelling software. This has led to significant changes in the way archaeological sites are documented. This paper entitled "Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology" by Jitte Waagen & Gert Jan van Wijngaarden (2024) presents an overview of the current developments in the application possibilities of 3D site topography recording in archaeology. The paper is the result of the round table discussion "Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology" at the CAA conference on 5 April 2023 in Amsterdam, with contributions from Radu Brunchi, Nicola Lercari, Joep Orbons, Davide Tanasi, Alicia Walsh, Pawel Wolf and Teagan Zoldoske. The paper starts with a discussion of the Amsterdam Troy Project (ATP). In the frame of the ATP, the rich history of archaeological activity (over 150 years of fieldwork) at Troy is being studied to explore how previous archaeological research has helped to shape the current topography of the site and how these earlier research activities, embedded in their contemporary theoretical frameworks, have determined our understanding of the site (see Murray and M. Spriggs 2017, Carver 2011 for the influence of theory on archaeological fieldwork and archaeology as a discipline), the so-called 'Archaeology of Archaeology' approach. In addition to studying previous research records and re-excavating old excavation trenches, a central element of the project is the 3D recording of the past and present topography of the site in order to reconstruct the archaeological research activities at the site and their impact on the archaeological landscape. The paper focuses on current trends in 3D recording of archaeological site topography and discusses three main areas where 3D recording of archaeological site topography can contribute to the "Archaeology of Archaeology" approach: (1) monitoring the topography of sites for preservation, conservation, research and dissemination purposes; (2) reconstructing, reevaluating and reinterpreting past archaeological research efforts; and (3) archiving in a 4D (GIS) environment. This is done using the example of the Amsterdam Troy project and comparing it with other projects using similar methods and approaches. Using these case studies, the authors effectively discuss the impact of these technologies on the understanding of the topography of archaeological sites and how 3D recording can enhance archaeological research methodologies and interpretations, for example, by not using such 3D approaches as a stand-alone product but integrating them with available information from previous research activities. They also recognise the limitations and challenges involved, such as the need for customised data acquisition strategies and the lack of ready-made software solutions for developing comprehensive data management strategies. One topic that could have been covered in more detail is how 3D site topography recording (and 3D recording in general) is affected by current theoretical developments in archaeology. Like any other archaeological fieldwork or data collection approach, it is a child of its time. Decisions such as what to record, how to record, what to store, how to store, what to visualise, and how to visualise influence our understanding of archaeological sites (Ward 2022). This minor critical reflection aside, the paper makes a timely and significant contribution to archaeology by addressing current trends and the limitations of the increasingly widespread use of 3D site topography recording technologies. References Carver, G. (2011). Reflections on the archaeology of archaeological excavation, Archaeological Dialogues 18(1), pp. 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203811000067 Murray, T. and Spriggs, M. (2017). The historiography of archaeology: exploring theory, contingency and rationality, World Archaeology 49(2), pp. 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2017.1334583 Ward, C. (2022). Excavating the Archive / Archiving the Excavation: Archival Processes and Contexts in Archaeology, Advances in Archaeological Practice 10(2), pp. 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2022.1 Waagen, J. and van Wijngaarden, G.J. (2024). Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology, Zenodo, 10061343, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommonded by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10061343 | Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology | Waagen, Jitte & Wijngaarden, Gert Jan van | <p>The current ubiquitous use of 3D recording technologies in archaeological fieldwork, for a large part due to the application of budget-friendly (drone) sensors and the availability of many low-cost image-based 3D modelling software packages, ha... |  | Computational archaeology, Remote sensing | Devi Taelman | 2023-10-17 23:03:47 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer