Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers▲ | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

21 Mar 2023

Automation and Novelty –Archaeocomputational Typo-Praxis in the Wake of the Third Science RevolutionRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Rachel Crellin and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Rachel Crellin and 1 anonymous reviewer

“Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology” submitted by G. Lucas (1) offers a refreshing and welcome reflection on the role of computer-based practice, type-thinking and approaches to typology in the age of big data and the widely proclaimed ‘Third Science Revolution’ (2–4). At the annual meeting of the EAA in Maastricht in 2017, a special thematic block was dedicated to issues and opportunities linked to the Third Science Revolution in archaeology “because of [its] profound and wide ranging impact on practice and theory in archaeology for the years to come” (5). Even though the Third Science Revolution, as influentially outlined by Kristiansen in 2014 (2), has occasionally also been met with skepticism and critique as to its often implicit scientism and epistemological naivety (6–8), archaeology as a whole seems largely euphoric as to the promises of the advancing ‘revolution’. As Lucas perceptively points out, some even regard it as the long-awaited opportunity to finally fulfil the ambitions and goals of Anglophone processualism. The irony here, as Lucas rightly notes, is that early processualists initially foregrounded issues of theory and scientific epistemology, while much work conducted under the banner of the Third Science Revolution, especially within its computational branches, does not. Big data advocates have echoed Anderson’s much-cited “end of theory” (9) or at least emphatically called for an ‘empirization’ and ‘computationalization’ of theory, often under the banner of ‘data-driven archaeology’ (10), yet typically without much specification of what this is supposed to mean for archaeological theory and reflexivity. The latter is indeed often openly opposed by archaeological Third Science Revolution enthusiasts, arguably because it is viewed as part of the supposedly misguided ‘post-modernist’ project. Lucas makes an original meta-archaeological contribution here and attempts to center the epistemological, ontological and praxeological dimensions of what is actually – in situated archaeological praxis and knowledge-production – put at stake by the mobilization of computers, algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI), including its many but presently under-reflected implications for ordering practices such as typologization. Importantly, his perspective thereby explicitly and deliberately breaks with the ‘normative project’ in traditional philosophy of science, which sought to nail down a universal, prescriptive way of doing science and securing scientific knowledge. He instead focuses on the practical dimensions and consequences of computer-reliant archaeologies, what actually happens on the ground as researchers try to grapple with the digital and the artefactual and try to negotiate new insights and knowledge, including all of the involved messiness – thereby taking up the powerful impetus of the broader practice turn in interdisciplinary science studies and STS (Science and Technology Studies (11)) (12–14), which have recently also re-oriented archaeological self-observation, metatheory and epistemology (15). This perspective on the dawning big data age in archaeology and incurred changes in the status, nature and aims of type-thinking produces a number of important insights, which Lucas fruitfully discusses in relation to promises of ‘automation’ and ‘novelty’ as these feature centrally in the rhetorics and politics of the Third Science Revolution. With regard to automation, Lucas makes the important point that machine or computer work as championed by big data proponents cannot adequately be qualified or understood if we approach the issue from a purely time-saving perspective. The question we have to ask instead is what work do machines actually do and how do they change the dynamics of archaeological knowledge production in the process? In this optic, automation and acceleration achieved through computation appear to make most sense in the realm of the uncontroversial, in terms of “reproducing an accepted way of doing things” as Lucas says, and this is precisely what can be observed in archaeological practice as well. The ramifications of this at first sight innocent realization are far-reaching, however. If we accept the noncontroversial claim that automation partially bypasses the need for specialists through the reproduction of already “pre-determined outputs”, automated typologization would primarily be useful in dealing with and synthesizing larger amounts of information by sorting artefacts into already accepted types rather than create novel types or typologies. If we identity the big data promise at least in part with automation, even the detection of novel patterns in any archaeological dataset used to construct new types cannot escape the fact that this novelty is always already prefigured in the data structure devised. The success of ‘supervised learning’ in AI-based approaches illustrates this. Automation thus simply shifts the epistemological burden back to data selection and preparation but this is rarely realized, precisely because of the tacit requirement of broad non-contentiousness. Minimally, therefore, big data approaches ironically curtail their potential for novelty by adhering to conventional data treatment and input formats, rarely problematizing the issue of data construction and the contested status of (observational) data themselves. By contrast, they seek to shield themselves against such attempts and tend to retain a tacit universalism as to the nature of archaeological data. Only in this way is it possible to claim that such data have the capacity to “speak for themselves”. To use a concept borrowed from complexity theory, archaeological automation-based type-construction that relies on supposedly basal, incontrovertible data inputs can only ever hope to achieve ‘weak emergence’ (16) – ‘strong emergence’ and therefore true, radical novelty require substantial re-thinking of archaeological data and how to construct them. This is not merely a technical question as sometimes argued by computational archaeologies – for example with reference to specifically developed, automated object tracing procedures – as even such procedures cannot escape the fundamental question of typology: which kind of observations to draw on in order to explore what aspects of artefactual variability (and why). The focus on readily measurable features – classically dimensions of artefactual form – principally evades the key problem of typology and ironically also reduces the complexity of artefactual realities these approaches assert to take seriously. The rise of computational approaches to typology therefore reintroduces the problem of universalism and, as it currently stands, reduces the complexity of observational data potentially relevant for type-construction in order to enable to exploration of the complexity of pattern. It has often been noted that this larger configuration promotes ‘data fetishism’ and because of this alienates practitioners from the archaeological record itself – to speak with Marxist theory that Lucas briefly touches upon. We will briefly return to the notion of ‘distance’ below because it can be described as a symptomatic research-logical trope (and even a goal) in this context of inquiry. In total, then, the aspiration for novelty is ultimately difficult to uphold if computational archaeologies refuse to engage in fundamental epistemological and reflexive self-engagement. As Lucas poignantly observes, the most promising locus for novelty is currently probably not to be found in the capacity of the machines or algorithms themselves, but in the modes of collaboration that become possible with archaeological practitioners and specialists (and possibly diverse other groups of knowledge stakeholders). In other words, computers, supercomputers and AI technologies do not revolutionize our knowledge because of their superior computational and pattern-detection capacities – or because of some mysterious ‘superintelligence’ – but because of the specific ‘division of labour’ they afford and the cognitive challenge(s) they pose. Working with computers and AI also often requires to ask new questions or at least to adapt the questions we ask. This can already be seen on the ground, when we pay attention to how machine epistemologies are effectively harnessed in archaeological practice (and is somewhat ironic given that the promise of computational archaeology is often identified with its potential to finally resolve "long-standing (old) questions"). The Third Science Revolution likely prompts a consequential transformation in the structural and material conditions of the kinds of ‘distributed’ processes of knowledge production that STS have documented as characteristic for scientific discoveries and knowledge negotiations more generally (14, 17, 18). This ongoing transformation is thus expected not only to promote new specializations with regard to the utilization of the respective computing infrastructures emerging within big data ecologies but equally to provoke increasing demand for new ways of conceptualizing observations and to reformulate the theoretical needs and goals of typology in archaeology. The rediscovery of reflexivity as an epistemic virtue within big data debates would be an important step into this direction, as it would support the shared goal of achieving true epistemic novelty, which, as Lucas points out, is usually not more than an elusive self-declaration. Big data infrastructures require novel modes of human-machine synergy, which simply cannot be developed or cultivated in an atheoretical and/or epistemological disinterested space. Lucas’ exploration ultimately prompts us to ask big questions (again), and this is why this is an important contribution. The elephant in the room, of course, is the overly strong notion of objectivity on which much computational archaeology is arguably premised – linked to the vow to eventually construct ‘objective typologies’. This proclivity, however, re-tables all the problematic debates of the 1960s and – to speak with the powerful root metaphor of the machine fueling much of causal-mechanistic science (19, 20) – is bound to what A. Wylie (21) and others have called the ‘view from nowhere’. Objectivity, in this latter view, is defined by the absence of positionality and subjectivity – chiefly human subjectivity – and the promise of the machine, and by extension of computational archaeology, is to purify and thus to enhance processes of knowledge production by minimizing human interference as much as possible. The distancing of the human from actual processes of data processing and inference is viewed as positive and sometimes even as an explicit goal of scientific development. Interestingly, alienation from the archaeological record is framed as an epistemic virtue here, not as a burden, because close connection with (or even worse, immersion in) the intricacies of artefacts and archaeological contexts supposedly aggravates the problem of bias. The machine, in this optic, is framed as the gatekeeper to an observer-independent reality – which to the backdoor often not only re-introduces Platonian/Aristotelian pledges to a quasi-eternal fabric of reality that only needs to be “discovered” by applying the right (broadly nonhuman) means, it is also largely inconsistent with defendable and currently debated conceptions of scientific objectivity that do not fall prey to dogma. Furthermore, current discussions on the open AI ChatGPT have exposed the enormous and still under-reflected dangers of leaning into radical renderings of machine epistemology: precisely because of the principles of automation and the irreducible theory-ladenness of all data, ecologies such as ChatGPT tend to reinforce the tacit epistemological background structures on which they operate and in this way can become collaborators in the legitimization and justification of the status quo (which again counteracts the potential for novelty) – they reproduce supposedly established patterns of thought. This is why, among other things, machines and AI can quickly become perpetuators of parochial and neocolonial projects – their supposed authority creates a sense of impartiality that shields against any possible critique. With Lucas, we can thus perhaps cautiously say that what is required in computational archaeology is to defuse the authority of the machine in favour of a new community archaeology that includes machines as (fallible) co-workers. Radically put, computers and AI should be recognized as subjects themselves, and treated as such, with interesting perspectives on team science and collaborative practice.

Bibliography 1. Lucas, G. (2022). Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology. https:/doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7620824. 2. Kristiansen, K. (2014). Towards a New Paradigm? The Third Science Revolution and its Possible Consequences in Archaeology. Current Swedish Archaeology 22, 11–34. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2014.01. 3. Kristiansen, K. (2022). Archaeology and the Genetic Revolution in European Prehistory. Elements in the Archaeology of Europe. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009228701 4. Eisenhower, M. S. (1964). The Third Scientific Revolution. Science News 85, 322/332. https://www.sciencenews.org/archive/third-scientific-revolution. 5. The ‘Third Science Revolution’ in Archaeology. http://www.eaa2017maastricht.nl/theme4 (March 16, 2023). 6. Ribeiro, A. (2019). Science, Data, and Case-Studies under the Third Science Revolution: Some Theoretical Considerations. Current Swedish Archaeology 27, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2019.06 7. Samida, S. (2019). “Archaeology in times of scientific omnipresence” in Archaeology, History and Biosciences: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, pp. 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110616651 8. Sørensen, T. F.. (2017). The Two Cultures and a World Apart: Archaeology and Science at a New Crossroads. Norwegian Archaeological Review 50, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2017.1367031 9. Anderson, C. (2008). The end of theory: The data deluge makes the scientific method obsolete. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/. 10. Gattiglia, G. (2015). Think big about data: Archaeology and the Big Data challenge. Archäologische Informationen 38, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.11588/ai.2015.1.26155 11. Hackett, E. J. (2008). The handbook of science and technology studies, Third edition, MIT Press/Society for the Social Studies of Science. 12. Ankeny, R., Chang, H., Boumans, M. and Boon, M. (2011). Introduction: philosophy of science in practice. Euro Jnl Phil Sci 1, 303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-011-0036-4 13. Soler, L., Zwart, S., Lynch, M., Israel-Jost, V. (2014). Science after the Practice Turn in the Philosophy, History, and Social Studies of Science, Routledge. 14. Latour, B. and Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: the construction of scientific facts, Princeton University Press. 15. Chapman, R. and Wylie, A. (2016) Evidential reasoning in archaeology, Bloomsbury Academic. 16. Greve, J. and Schnabel, A. (2011). Emergenz: zur Analyse und Erklärung komplexer Strukturen, Suhrkamp. 17. Shapin, S., Schaffer, S. and Hobbes, T. (1985). Leviathan and the air-pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life, including a translation of Thomas Hobbes, Dialogus physicus de natura aeris by Simon Schaffer, Princeton University Press. 18. Galison, P. L. and Stump, D. J. (1996).The Disunity of Science: Boundaries, Contexts, and Power, Stanford University Press. 19. Pepper, S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print, University of California Press. 20. Hussain, S. T. (2019). The French-Anglophone divide in lithic research: A plea for pluralism in Palaeolithic Archaeology, Open Access Leiden Dissertations. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/69812 21. A. Wylie, A. (2015). “A plurality of pluralisms: Collaborative practice in archaeology” in Objectivity in Science, pp. 189-210, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14349-1_10 | Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology | Gavin Lucas | <p>In this paper, I will explore some of the implications of machine learning for archaeological method and theory. Against a back-drop of the rise of Big Data and the Third Science Revolution, what lessons can be drawn from the use of new digital... | Computational archaeology, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | Anonymous, Rachel Crellin | 2022-10-31 15:25:38 | View | |

01 Sep 2023

Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854))Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552A zooarchaeological perspective on testudine bones from Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Southeast AsiaRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta

The study of the evolution of the human diet has been a central theme in numerous archaeological and paleoanthropological investigations. By reconstructing diets, researchers gain deeper insights into how humans adapted to their environments. The analysis of animal bones plays a crucial role in extracting dietary information. Most studies involving ancient diets rely heavily on zooarchaeological examinations, which, due to their extensive history, have amassed a wealth of data. During the Pleistocene–Holocene periods, testudine bones have been commonly found in a multitude of sites. The use of turtles and tortoises as food sources appears to stretch back to the Early Pleistocene [1-4]. More importantly, these small animals play a more significant role within a broader debate. The exploitation of tortoises in the Mediterranean Basin has been examined through the lens of optimal foraging theory and diet breadth models (e.g. [5-10]). According to the diet breadth model, resources are incorporated into diets based on their ranking and influenced by factors such as net return, which in turn depends on caloric value and search/handling costs [11]. Within these theoretical frameworks, tortoises hold a significant position. Their small size and sluggish movement require minimal effort and relatively simple technology for procurement and processing. This aligns with optimal foraging models in which the low handling costs of slow-moving prey compensate for their small size [5-6,9]. Tortoises also offer distinct advantages. They can be easily transported and kept alive, thereby maintaining freshness for deferred consumption [12-14]. For example, historical accounts suggest that Mexican traders recognised tortoises as portable and storable sources of protein and water [15]. Furthermore, tortoises provide non-edible resources, such as shells, which can serve as containers. This possibility has been discussed in the context of Kebara Cave [16] and noted in ethnographic and historical records (e.g. [12]). However, despite these advantages, their slow growth rate might have rendered intensive long-term predation unsustainable. While tortoises are well-documented in the Southeast Asian archaeological record, zooarchaeological analyses in this region have been limited, particularly concerning prehistoric hunter-gatherer populations that may have relied extensively on inland chelonian taxa. With the present paper Bochaton et al. [17] aim to bridge this gap by conducting an exhaustive zooarchaeological analysis of turtle bone specimens from four Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Thailand and Cambodia. These assemblages span from the Late Pleistocene to the first half of the Holocene. The authors focus on bones attributed to the yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata), which is the most prevalent taxon in the assemblages. The research include osteometric equations to estimate carapace size and explore population structures across various sites. The objective is to uncover human tortoise exploitation strategies in the region, and the results reveal consistent subsistence behaviours across diverse locations, even amidst varying environmental conditions. These final proposals suggest the possibility of cultural similarities across different periods and regions in continental Southeast Asia. In summary, this paper [17] represents a significant advancement in the realm of zooarchaeological investigations of small prey within prehistoric communities in the region. While certain approaches and issues may require further refinement, they serve as a comprehensive and commendable foundation for assessing human hunting adaptations.

References [1] Hartman, G., 2004. Long-term continuity of a freshwater turtle (Mauremys caspica rivulata) population in the northern Jordan Valley and its paleoenvironmental implications. In: Goren-Inbar, N., Speth, J.D. (Eds.), Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 61-74. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dtct.11 [2] Alperson-Afil, N., Sharon, G., Kislev, M., Melamed, Y., Zohar, I., Ashkenazi, R., Biton, R., Werker, E., Hartman, G., Feibel, C., Goren-Inbar, N., 2009. Spatial organization of hominin activities at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. Science 326, 1677-1680. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180695 [3] Archer, W., Braun, D.R., Harris, J.W., McCoy, J.T., Richmond, B.G., 2014. Early Pleistocene aquatic resource use in the Turkana Basin. J. Hum. Evol. 77, 74-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.02.012 [4] Blasco, R., Blain, H.A., Rosell, J., Carlos, D.J., Huguet, R., Rodríguez, J., Arsuaga, J.L., Bermúdez de Castro, J.M., Carbonell, E., 2011. Earliest evidence for human consumption of tortoises in the European Early Pleistocene from Sima del Elefante, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain. J. Hum. Evol. 11, 265-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.06.002 [5] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N., Surovell, T.A., Tchernov, E., Bar-Yosef, O., 1999. Palaeolithic growth pulses evidenced by small animal exploitation. Science 283, 190-194. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5399.190 [6] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., Surovell, T.A., 2000. The tortoise and the hare: small-game use, the Broad-Spectrum Revolution, and paleolithic demography. Curr. Anthropol. 41, 39-73. https://doi.org/10.1086/300102 [7] Stiner, M.C., 2001. Thirty years on the “Broad Spectrum Revolution” and paleolithic demography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 (13), 6993-6996. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.121176198 [8] Stiner, M.C., 2005. The Faunas of Hayonim Cave (Israel): a 200,000-Year Record of Paleolithic Diet. Demography and Society. American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 48. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge. [9] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., 2002. Approaches to prehistoric diet breadth, demography, and prey ranking systems in time and space. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 9, 181-214. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016530308865 [10] Blasco, R., Cochard, D., Colonese, A.C., Laroulandie, V., Meier, J., Morin, E., Rufà, A., Tassoni, L., Thompson, J.C. 2022. Small animal use by Neanderthals. In Romagnoli, F., Rivals, F., Benazzi, S. (eds.), Updating Neanderthals: Understanding Behavioral Complexity in the Late Middle Palaeolithic. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 123-143. ISBN 978-0-12-821428-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2019-0-03240-2 [11] Winterhalder, B., Smith, E.A., 2000. Analyzing adaptive strategies: human behavioural ecology at twenty-five. Evol. Anthropol. 9, 51-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(2000)9:2%3C51::aid-evan1%3E3.0.co;2-7 [12] Schneider, J.S., Everson, G.D., 1989. The Desert Tortoise (Xerobates agassizii) in the Prehistory of the Southwestern Great Basin and Adjacent areas. J. Calif. Gt. Basin Anthropol. 11, 175-202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825383 [13] Thompson, J.C., Henshilwood, C.S., 2014b. Nutritional values of tortoises relative to ungulates from the Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa: implications for foraging and social behaviour. J. Hum. Evol. 67, 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.010 [14] Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Smith, K.T., Maul, L.Ch., Sañudo, P., Barkai, R., Gopher, A. 2016. Tortoises as a Dietary Supplement: a view from the Middle Pleistocene site of Qesem Cave, Israel. Quat Sci Rev 133, 165-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.12.006 [15] Pepper, C., 1963. The truth about the tortoise. Desert Mag. 26, 10-11. [16] Speth, J.D., Tchernov, E., 2002. Middle Paleolithic tortoise use at Kebara Cave (Israel). J. Archaeol. Sci. 29, 471-483. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2001.0740 [17] Bochaton, C., Chantasri, S., Maneechote, M., Claude, J., Griggo, C., Naksri, W., Forestier, H., Sophady, H., Auertrakulvit, P., Bowonsachoti, J. and Zeitoun, V. (2023) Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed Tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854)), BioRXiv, 2023.04.27.538552 , ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552v3 | Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (*Indotestudo elongata* (Blyth, 1854)) | Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun | <p style="text-align: justify;">While non-marine turtles are almost ubiquitous in the archaeological record of Southeast Asia, their zooarchaeological examination has been inadequately pursued within this tropical region. This gap in research hind... |  | Asia, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Iratxe Boneta, Noel Amano | 2023-05-02 09:30:50 | View |

26 Mar 2024

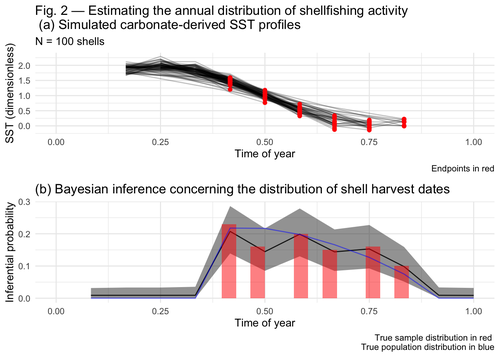

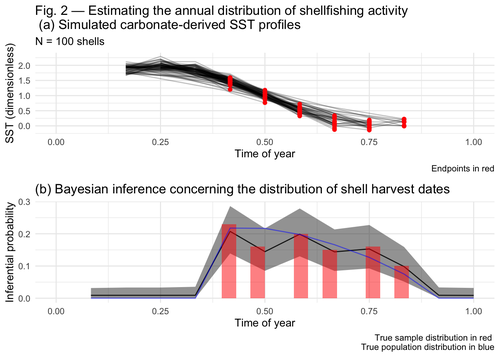

Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approachJordan Brown and Gabriel Lewis https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7949547Mixture models and seasonal mobilityRecommended by Alfredo Cortell-Nicolau and Simon Carrignon based on reviews by Iza Romanowska and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper by Brown & Lewis [1] presents an approach to measure seasonal mobility and subsistence practices. In order to do so, the paper proposes a Bayesian mixture model to estimate the annual distribution of shellfish harvesting activity. Following the recommendations of the two reviewers, the paper presents a clear and innovative method to assess seasonal mobility for prehistoric groups, although it could benefit from additional references regarding isotopic literature. While the adequacy of isotope analysis for estimating mobility patterns in Archaeology has been extensively proven by now, work on specific seasonal mobility is not that much abundant. However, this is a key issue, since seasonal mobility is one of the main social components defining the differences between groups both considering farming vs hunting and gathering or even among hunter-gatherer groups themselves. In this regard, the paper brings a valuable methodological resources that can be used for further research in this issue. One of its greatest values is the fact that it can quantify the uncertainty present in previous isotope studies in seasonal mobility. As stated by the authors, the model can still undergo several optimisation aspects, but as it stands, it is already providing a valuable asset regarding the quantification of uncertainy in the isotopic studies of seasonal mobility. Reference [1] Brown, J. and Lewis, G. (2024). Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approach. Zenodo, 7949547, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7949547 | Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approach | Jordan Brown and Gabriel Lewis | <p>The problem of accurately and reliably estimating the annual distribution of seasonally-varying human settlement and subsistence practices is a classic concern among archaeologists, which has only become more relevant with the increasing import... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology, Environmental archaeology, North America, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Alfredo Cortell-Nicolau | Iza Romanowska, Eduardo Herrera Malatesta, Alejandro Sierra Sainz-Aja, Sam Leggett, Christianne Fernee, Anonymous, Asier García-Escárzaga , Paul Szpak , Maria Elena Castiello , Jasmine Lundy , Tansy Branscombe | 2023-10-03 04:45:54 | View |

20 Jul 2022

Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, IsraelNimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4New zooarchaeological data from the Upper Palaeolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2, IsraelRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio

The Levantine Corridor is considered a crossing point to Eurasia and one of the main areas for detecting population flows (and their associated cultural and economic changes) during the Pleistocene. This area could have been closed during the most arid periods, giving rise to processes of population isolation between Africa and Eurasia and intermittent contact between Eurasian human communities [1,2]. Zooarchaeological studies of the early Upper Palaeolithic assemblages constitute an important source of knowledge about human subsistence, making them central to the debate on modern behaviour. The Early Upper Palaeolithic sequence in the Levant includes two cultural entities – the Early Ahmarian and the Levantine Aurignacian. This latter is dated to 39-33 ka and is considered a local adaptation of the European Aurignacian techno-complex. In this work, the authors present a zooarchaeological study of the Nahal Rahaf 2 (ca. 35 ka) archaeological site in the southern Judean Desert in Israel [3]. Zooarchaeological data from the early Upper Paleolithic desert regions of the southern Levant are not common due to preservation problems of non-lithic finds. In the case of Nahal Rahaf 2, recent excavation seasons brought to light a stratigraphical sequence composed of very well-preserved archaeological surfaces attributed to the 'Arkov-Divshon' cultural entity, which is associated with the Levantine Aurignacian. This study shows age-specific caprine (Capra cf. Capra ibex) hunting on prime adults and a generalized procurement of gazelles (Gazella cf. Gazella gazella), which seem to have been selectively transported to the site and processed for within-bone nutrients. An interesting point to note is that the proportion of goats increases along the stratigraphic sequence, which suggests to the authors a specialization in the economy over time that is inversely related to the occupational intensity of use of the site. It is also noteworthy that the materials represent a large sample compared to previous studies from the Upper Paleolithic of the Judean Desert and Negev. In summary, this manuscript contributes significantly to the study of both the palaeoenvironment and human subsistence strategies in the Upper Palaeolithic and provides another important reference point for evaluating human hunting adaptations in the arid regions of the southern Levant. References [1] Bermúdez de Castro, J.-L., Martinon-Torres, M. (2013). A new model for the evolution of the human pleistocene populations of Europe. Quaternary Int. 295, 102-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.036 [2] Bar-Yosef, O., Belfer-Cohen, A. (2010). The Levantine Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic. In Garcea, E.A.A. (Ed), South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples Between 130,000 and 10,000 Years Ago. Oxbow Books, pp. 144-167. [3] Marom, N., Gnezdilov, D. L., Shafir, R., Barzilai, O. and Shemer, M. (2022). Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel. BioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492258, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4 | Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel | Nimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer | <p>Nahal Rahaf 2 (NR2) is an Early Upper Paleolithic (ca. 35 kya) rock shelter in the southern Judean Desert in Israel. Two excavation seasons in 2019 and 2020 revealed a stratigraphical sequence composed of intact archaeological surfaces attribut... |  | Upper Palaeolithic, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Joana Gabucio | 2022-05-19 06:16:47 | View |

03 Nov 2023

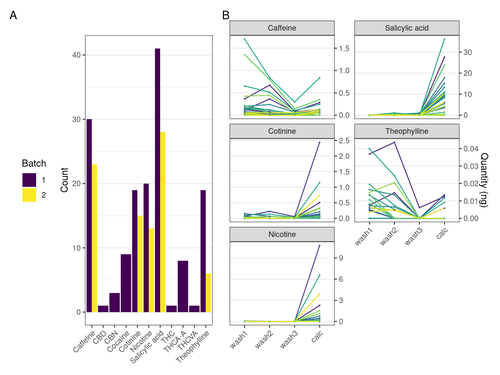

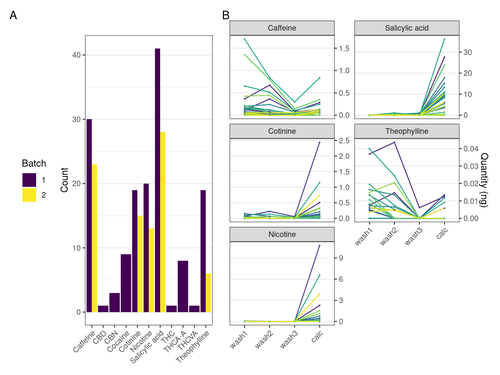

Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch populationBartholdy, Bjørn Peare; Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B.; Sørensen, Lambert K.; Casna, Maia; Hoogland, Menno; Historisch Genootschap Beemster; Henry, Amanda G. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7649150Detection of plant-derived compounds in XIXth c. Dutch dental calculusRecommended by Louise Le Meillour based on reviews by Mario Zimmerman and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Mario Zimmerman and 2 anonymous reviewers

The advent of biomolecular methods has certainly increased our overall comprehension of archaeological societies. One of the materials of choice to perform ancient DNA or proteomics analyses is dental calculus[1,2], a mineralised biofilm formed during the life of one individual. Research conducted in the past few decades has demonstrated the potential of dental calculus to retrieve information about past societies health[3–6], diet[7–11], and more recently, as a putative proxy for isotopic analyses[12].

Bartholdy et al. utilised the developed LC-MS/MS method to 41 buried individuals, most of them bearing pipe notches on their teeth, from the cemetery of the 19th rural settlement of Middenbeemster, the Netherlands. Along with dental calculus sampling and analysis, they undertook the skeletal and dental examination of all of the specimens in order to assess sex, age-at-death, and pathology on the two tissues. The results obtained on the dental calculus of the sampled individuals show probable consumption of tea, coffee and tobacco indicated by the detection of the various plant compounds and associated metabolites (caffeine, nicotine and salicylic acid, amongst others). The authors were able to place their results in perspective and propose several interpretations concerning the ingestion of plant-derived products, their survival in dental calculus and the importance of their findings for our overall comprehension of health and habits of the XIXth c. Dutch population. The paper is well-written and accessible to a non-specialist audience, maximising the impact of their study. I personally really enjoyed handling this manuscript that is not only a good piece of scientific literature but also a pleasant read, the reason why I warmly recommend this paper to be accessible through PCI Archaeology. References 1. Fagernäs, Z. and Warinner, C. (2023) Dental Calculus. in Handbook of Archaeological Sciences 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119592112.ch28 2. Wright, S. L., Dobney, K. & Weyrich, L. S. (2021) Advancing and refining archaeological dental calculus research using multiomic frameworks. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 7, 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2021.1882122 3. Fotakis, A. K. et al. (2020) Multi-omic detection of Mycobacterium leprae in archaeological human dental calculus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 375, 20190584. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0584 4. Warinner, C. et al. (2014) Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nat. Genet. 46, 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2906 5. Weyrich, L. S. et al. (2017) Neanderthal behaviour, diet, and disease inferred from ancient DNA in dental calculus. Nature 544, 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21674 6. Jersie-Christensen, R. R. et al. (2018) Quantitative metaproteomics of medieval dental calculus reveals individual oral health status. Nat. Commun. 9, 4744. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07148-3 7. Hendy, J. et al. (2018) Proteomic evidence of dietary sources in ancient dental calculus. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.0977 8. Wilkin, S. et al. (2020) Dairy pastoralism sustained eastern Eurasian steppe populations for 5,000 years. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1120-y 9. Bleasdale, M. et al. (2021) Ancient proteins provide evidence of dairy consumption in eastern Africa. Nat. Commun. 12, 632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20682-3 10. Warinner, C. et al. (2014) Direct evidence of milk consumption from ancient human dental calculus. Sci. Rep. 4, 7104. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07104 11. Buckley, S., Usai, D., Jakob, T., Radini, A. and Hardy, K. (2014) Dental Calculus Reveals Unique Insights into Food Items, Cooking and Plant Processing in Prehistoric Central Sudan. PLoS One 9, e100808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100808 12. Salazar-García, D. C., Warinner, C., Eerkens, J. W. and Henry, A. G. (2023) The Potential of Dental Calculus as a Novel Source of Biological Isotopic Data. in Exploring Human Behavior Through Isotope Analysis: Applications in Archaeological Research (eds. Beasley, M. M. & Somerville, A. D.) 125–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32268-6_6 13. Sørensen, L. K., Hasselstrøm, J. B., Larsen, L. S. and Bindslev, D. A. (2021) Entrapment of drugs in dental calculus - Detection validation based on test results from post-mortem investigations. Forensic Sci. Int. 319, 110647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110647 14. Bartholdy, Bjørn Peare, Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B., Sørensen, Lambert K., Casna, Maia, Hoogland, Menno, Historisch Genootschap Beemster and Henry, Amanda G. (2023) Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch population, Zenodo, 7649150, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7649150 | Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch population | Bartholdy, Bjørn Peare; Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B.; Sørensen, Lambert K.; Casna, Maia; Hoogland, Menno; Historisch Genootschap Beemster; Henry, Amanda G. | <p>Dental calculus is an excellent source of information on the dietary patterns of past populations, including consumption of plant-based items. The detection of plant-derived residues such as alkaloids and their metabolites in dental calculus pr... |  | Bioarchaeology, Post-medieval | Louise Le Meillour | Mario Zimmerman, Anonymous | 2023-07-31 17:21:40 | View |

19 Feb 2024

Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias ReductionFumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330Evaluating Methods for Reducing Sampling Bias in Network AnalysisRecommended by James Allison based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer

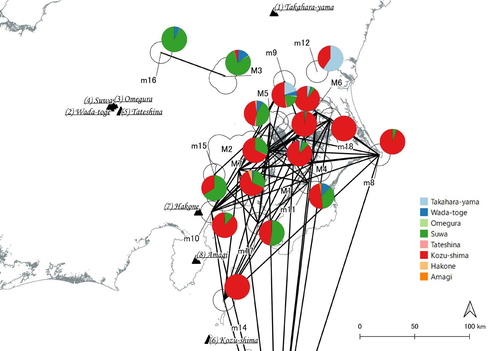

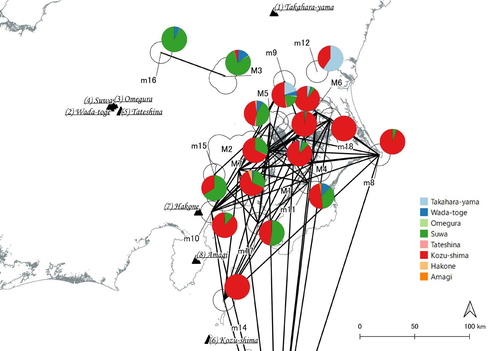

In a recent article, Fumihiro Sakahira and Hiro'omi Tsumura (2023) used social network analysis methods to analyze change in obsidian trade networks in Japan throughout the 13,000-year-long Jomon period. In the paper recommended here (Sakahira and Tsumura 2024), Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction they revisit that data and describe additional analyses that confirm the robustness of their social network analysis. The data, analysis methods, and substantive conclusions of the two papers overlap; what this new paper adds is a detailed examination of the data and methods, including use of bootstrap analysis to demonstrate the reasonableness of the methods they used to group sites into clusters. Both papers begin with a large dataset of approximately 21,000 artifacts from more than 250 sites dating to various times throughout the Jomon period. The number of sites and artifacts, varying sample sizes from the sites, as well as the length of the Jomon period, make interpretation of the data challenging. To help make the data easier to interpret and reduce problems with small sample sizes from some sites, the authors assign each site to one of five sub-periods, then define spatial clusters of sites within each period using the DBSCAN algorithm. Sites with at least three other sites within 10 km are joined into clusters, while sites that lack enough close neighbors are left as isolates. Clusters or isolated sites with sample sizes smaller than 30 were dropped, and the remaining sites and clusters became the nodes in the networks formed for each period, using cosine similarities of obsidian assemblages to define the strength of ties between clusters and sites. The main substantive result of Sakahira and Tsumura’s analysis is the demonstration that, during the Middle Jomon period (5500-4500 cal BP), clusters and isolated sites were much more connected than before or after that period. This is largely due to extensive distribution of obsidian from the Kozu-shima source, located on a small island off the Japanese mainland. Before the Middle Jomon period, Kozu-shima obsidian was mostly found at sites near the coast, but during the Middle Jomon, a trade network developed that took Kozu-shima obsidian far inland. This ended after the Middle Jomon period, and obsidian networks were less densely connected in the late and last Jomon periods. The methods and conclusions are all previously published (Sakahira and Tsumura 2023). What Sakahira and Tsumura add in Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction are: · an examination of the distribution of cosine similarities between their clusters for each period · a similar evaluation of the cosine similarities within each cluster (and among the unclustered sites) for each period · bootstrap analyses of the mean cosine similarities and network densities for each time period These additional analyses demonstrate that the methods used to cluster sites are reasonable, and that the use of spatially defined clusters as nodes (rather than the individual sites within the clusters) works well as a way of reducing bias from small, unrepresentative samples. An alternative way to reduce that bias would be to simply drop small assemblages, but that would mean ignoring data that could usefully contribute to the analysis. The cosine similarities between clusters show patterns that make sense given the results of the network analysis. The Middle Jomon period has, on average, the highest cosine similarities between clusters, and most cluster pairs have high cosine similarities, consistent with the densely connected, spatially expansive network from that time period. A few cluster pairs in the Middle Jomon have low similarities, apparently representing comparisons including one of the few nodes on the margins on the network that had little or no obsidian from the Kozu-shima source. The other four time periods all show lower average inter-cluster similarities and many cluster pairs have either high or low similarities. This probably reflects the tendency for nearby clusters to have very similar obsidian assemblages to each other and for geographically distant clusters to have dissimilar obsidian assemblages. The pattern is consistent with the less densely connected networks and regionalization shown in the network graphs. Thinking about this pattern makes me want to see a plot of the geographic distances between the clusters against the cosine similarities. There must be a very strong correlation, but it would be interesting to know whether there are any cluster pairs with similarities that deviate markedly from what would be predicted by their geographic separation. The similarities within clusters are also interesting. For each time period, almost every cluster has a higher average (mean and median) within-cluster similarity than the similarity for unclustered sites, with only two exceptions. This is partial validation of the method used for creating the spatial clusters; sites within the clusters are at least more similar to each other than unclustered sites are, suggesting that grouping them this way was reasonable. Although Sakahira and Tsumura say little about it, most clusters show quite a wide range of similarities between the site pairs they contain; average within-cluster similarities are relatively high, but many pairs of sites in most clusters appear to have low similarities (the individual values are not reported, but the pattern is clear in boxplots for the first four periods). There may be value in further exploring the occurrence of low site-to-site similarities within clusters. How often are they caused by small sample sizes? Clusters are retained in the analysis if they have a total of at least 30 artifacts, but clusters may contain sites with even smaller sample sizes, and small samples likely account for many of the low similarity values between sites in the same cluster. But is distance between sites in a cluster also a factor? If the most distant sites within a spatially extensive cluster are dissimilar, subdividing the cluster would likely improve the results. Further exploration of these within-cluster site-to-site similarity values might be worth doing, perhaps by plotting the similarities against the size of the smallest sample included in the comparison, as well as by plotting the cosine similarity against the distance between sites. Any low similarity values not attributable to small sample sizes or geographic distance would surely be worth investigating further. Sakahira and Tsumura also use a bootstrap analysis to simulate, for each time period, mean cosine similarities between clusters and between site pairs without clustering. They also simulate the network density for each time period before and after clustering. These analyses show that, almost always, mean simulated cosine similarities and mean simulated network density are higher after clustering than before. The simulated mean values also match the actual mean values better after clustering than before. This improved match to actual values when the sites are clustered for the bootstrap reinforces the argument that clustering the sites for the network analysis was a reasonable result. The strength of this paper is that Sakahira and Tsumura return to reevaluate their previously published work, which demonstrated strong patterns through time in the nature and extent of Jomon obsidian trade networks. In the current paper they present further analyses demonstrating that several of their methodological decisions were reasonable and their results are robust. The specific clusters formed with the DBSCAN algorithm may or may not be optimal (which would be unreasonable to expect), but the authors present analyses showing that using spatial clusters does improve their network analysis. Clustering reduces problems with small sample sizes from individual sites and simplifies the network graphs by reducing the number of nodes, which makes the results easier to interpret. Reference Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2023). Tipping Points of Ancient Japanese Jomon Trade Networks from Social Network Analyses of Obsidian Artifacts. Frontiers in Physics 10:1015870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.1015870 Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2024). Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction, Zenodo, 10057602, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330 | Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction | Fumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura | <p>This study aims to investigate the dynamics of obsidian trade networks during the Jomon period (approximately 15,000 to 2,400 years ago), the hunting and gathering era in Japan. To improve regional representation and reduce the distortions caus... |  | Asia, Computational archaeology | James Allison | Thegn Ladefoged, Matthew Peeples | 2023-05-28 05:51:12 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer