Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Sep 2023

Research workflows, paradata, and information visualisation: feedback on an exploratory integration of issues and practices - MEMORIA ISDudek Iwona, Blaise Jean-Yves https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8311129Using information visualisation to improve traceability, transmissibility and verifiability in research workflowsRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Adéla Sobotkova and 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper “Research workflows, paradata, and information visualisation: feedback on an exploratory integration of issues and practices - MEMORIA IS” (Dudek & Blaise, 2023) describes a prototype of an information system developed to improve the traceability, transmissibility and verifiability of archaeological research workflows. A key aspect of the work with MEMORIA is to make research documentation and the workflows underpinning the conducted research more approachable and understandable using a series of visual interfaces that allow users of the system to explore archaeological documentation, including metadata describing the data and paradata that describes its underlying processes. The work of Dudek and Blaise address one of the central barriers to reproducibility and transparency of research data and propose a set of both theoretically and practically well-founded tools and methods to solve this major problem. From the reported work on MEMORIA IS, information visualisation and the proposed tools emerge as an interesting and potentially powerful approach for a major push in improving the traceability, transmissibility and verifiability of research data through making research workflows easier to approach and understand. In comparison to technical work relating to archaeological data management, this paper starts commendably with a careful explication of the conceptual and epistemic underpinnings of the MEMORIA IS both in documentation research, knowledge organisation and information visualisation literature. Rather than being developed on the basis of a set of opaque assumptions, the meticulous description of the MEMORIA IS and its theoretical and technical premises is exemplary in its transparence and richness and has potential for a long-term impact as a part of the body of literature relating to the development of archaeological documentation and documentation tools. While the text is sometimes fairly densely written, it is worth taking the effort to read it through. Another major strength of the paper is that it provides a rich set of examples of the workings of the prototype system that makes it possible to develop a comprehensive understanding of the proposed approaches and assess their validity. As a whole, this paper and the reported work on MEMORIA IS forms a worthy addition to the literature on and practical work for developing critical infrastructures for data documentation, management and access in archaeology. Beyond archaeology and the specific context of the discussed work discussed this paper has obvious relevance to comparable work in other fields. ReferencesDudek, I. and Blaise, J.-Y. (2023) Research workflows, paradata, and information visualisation: feedback on an exploratory integration of issues and practices - MEMORIA IS, Zenodo, 8252923, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8252923

| Research workflows, paradata, and information visualisation: feedback on an exploratory integration of issues and practices - MEMORIA IS | Dudek Iwona, Blaise Jean-Yves | <p>The paper presents an exploratory web information system developed as a reaction to practical and epistemological questions, in the context of a scientific unit studying the architectural heritage (from both historical sciences perspective, and... |  | Computational archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-02 12:50:39 | View | |

16 May 2024

A return to function as the basis of lithic classificationRadu Iovita https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7734147Using insights from psychology and primatology to reconsider function in lithic typologiesRecommended by Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Vincent Delvigne and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Vincent Delvigne and 1 anonymous reviewer

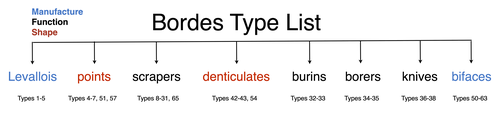

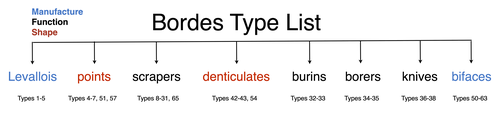

The paper “A return to function as the basis of lithic classification” by Radu Iovita (2024) is a contribution to an upcoming volume on the role of typology and type-thinking in current archaeological theory and praxis edited by the PCI recommenders. In this context, the paper offers an in-depth discussion of several crucial dimensions of typological thinking in past and current lithic studies, namely:

Discussing and importantly re-articulating these concepts, Iovita ultimately aims at “establishing unified guiding principles for studying a technology that spans several million years and several different species whose brain capacities range from ca. 300–1400 cm³”. The notion that tool function should dictate classification is not new (e.g. Gebauer 1987). It is particularly noteworthy, however, that the paper engages carefully with various relevant contributions on the topic from non-Anglophone research traditions. First, its considering works on lithic typologies published in other languages, such as Russian (Sergei Semenov), French (Georges Laplace), and German (Joachim Hahn). Second, it takes up the ideas of two French techno-anthropologists, in particular:

Interestingly, Iovita grounds his argumentation on insights from primatology, psychology and the cognitive sciences, to the extent that they fuel discussion on archaeological concepts and methods. Results regarding the so-called “design stance” for example play a crucial role: coined by philosopher and cognitive scientist and philosopher Daniel Dennett (1942-2024), this notion encompasses the possible discrepancies between the designer’s intended purpose and the object's current functions. DIF, as discussed by Iovita, directly relates to this idea, illustrating how concepts from other sciences can fruitfully be injected into archaeological thinking. Lastly, readers should note the intellectual contents generated on PCI as part of the reviewing process of the paper itself: both the reviewers and the author have engaged in in-depth discussions on the idea of (tool) “function” and its contested relationship with form or typology, delineating and mapping different views on these key issues in lithic study which are worth reading on their own. ReferencesGebauer, A. B. (1987). Stylistic Analysis. A Critical Review of Concepts, Models, and Interpretations, Journal of Danish Archaeology, 6, p. 223–229. Geertz, C. (1975). Common Sense as a Cultural System, The Antioch Review, 33 (1), p. 5–26. Iovita, R. (2024). A return to function as the basis of lithic classification. Zenodo, 7734147, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7734147 Lévi-Strauss, C. (1962). La pensée sauvage. Paris: Plon. Lévi-Strauss, C. (2021). Wild Thought: A New Translation of “La Pensée sauvage”. Translated by Jeffrey Mehlman & John Leavitt. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l'analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d'études technologiques en préhistoire : Bilan et perspectives, Juan-les-Pins: Éditions de l'association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques, p. 21-34. | A return to function as the basis of lithic classification | Radu Iovita | <p>Complex tool use is one of the defining characteristics of our species, and, because of the good preservation of stone tools (lithics), one of the few which can be studied on the evolutionary time scale. However, a quick look at the lithics lit... |  | Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Theoretical archaeology, Traceology | Sébastien Plutniak | 2023-03-14 19:01:40 | View | |

07 May 2024

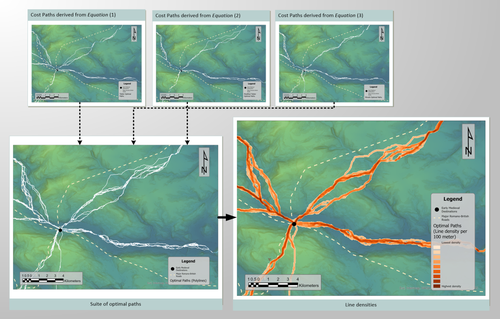

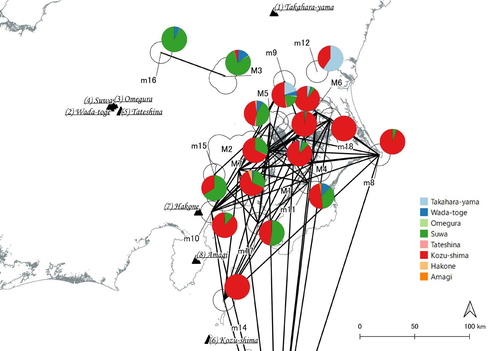

Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West EnglandWyatt Wilcox https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7999149Moving away from the ritual deposition: hoards from the Viking Age, Least Cost Paths and reused Roman RoadsRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Sam Leggett and Scott Madry based on reviews by Sam Leggett and Scott Madry

I had the pleasure of reading ‘Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England’ by Wyatt O. Wilcox (Wilcox 2024a). It is an honour to recommend this paper. The aim of this study is to research the relationship of 18 Viking Age hoards and their transport and depositional locations. This is studied in relation to the Roman road network and the landscape using least cost path analyses. Single finds from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (https://finds.org.uk/) are also incorporated in the study. The study deals with the distance of these Viking Age finds to these roads/least-cost-paths and the final interpretation moves away from ritual interpretation of these finds to a more mundane explanation. I feel that this could potentially open discussion also for hoards from other periods. While both reviewers (Sam Leggett and Scott Madry) presented various suggestions to improve the first submitted version of the paper, the author has done a tremendous job to improve the paper based on the comments and even beyond these comments. The author has also deposited the Jypiter-notebook online (Wilcox 2024b), showing that he is contributing to Open Science. The first version of the dataset has been improved and updated based on the comments by the reviewers and me, improving the reproducibility of the analyses. All in all, this paper has improved and I am very glad that I can recommend this for publication, and I’d like to do so with a sentence from the review by Sam Leggett: “this study has a lot of potential to be deployed across other regions, and time periods for similar purposes (Iron Age hoards for instance). And it will be of great interest to Viking Age experts interested in hoards, but also early medieval transport and travel.” References Wilcox, W. 2024a Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England. Zenodo, 7999149, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7999149 Wilcox, W. 2024b Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England (Supplemental Material). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11067607 | Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England | Wyatt Wilcox | <p>Discussions on Viking Age silver hoards in North West England have been dominated by analysis of the material compositions of the hoards. Despite a multi-century research legacy concerning the material composition of the Viking Age silver... |  | Europe, Landscape archaeology, Medieval, Spatial analysis | Ronald Visser | 2023-06-04 22:29:18 | View | |

01 Dec 2021

A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-MaatheideSonja Tomasso, Dries Cnuts, Justin Coppe, Marijn Van Gils, Ferdi Geerts, Marc De Bie, Veerle Rots https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pf3smPotential of a large-scale functional analysis to reconstructing past human activities at the Final Palaeolithic site of Lommel-MaatheideRecommended by Marta Arzarello and Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti and Ana Abrunhosa and Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti and Ana Abrunhosa

The paper “A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide” [1] focuses on the final Palaeolithic (Federmesser) site of Lommel-Maatheide. Federmesser sites from northern Belgium such as Lommel-Maatheide, Meer and Rekem, show evidence for dense human occupation of specific areas located on top of Tardiglacial dunes nearby water bodies [2]. Preserved spatial distribution of finds at the sites suggest different activity areas and the presence of habitat structures [2]. However, because of the low organic preservation at the sites, functional analyses of lithic assemblages have the potential to significantly contribute to the spatial organisation of activities at these sites. This study by Tomasso et al. [1], represents an excellent example of a large-scale integrated approach to the study of lithic industries. The article undoubtedly demonstrates the potential of the proposed methodology and the reliability of the results obtained. The article explores two different aspects (linked and excellently interconnected here): the possibility to apply use wear, residue and fracture analyses, on lithic assemblages affected by taphonomical alterations and to study lithic assemblages from dune landscapes. The study allows to answer differentiated questions: what is the influence of taphonomical alterations on use wear analysis? How do excavation methods impact the formation of use wear and the preservation of residues? Can we recognize distinct domestic activities? The article also provides an interesting hypothesis about hunting activities and propulsion methods. The applied methodology is effectively interdisciplinary and innovative. It demonstrates how a truly integrated and articulated approach can represent the turning point for going beyond a mainly descriptive dimension to move towards a real understanding of the sites. Studies dedicated to the analysis of the propulsion mode are not very frequent, but they are surely very important to better understand human behaviour [3]. Here, the methodology developed for the evaluation of the propulsion mode represent an important starting point for the definition of a new approach. Morphological and morphometrical analysis are integrated to the evaluation of the mechanical stress, to fracture delineations and to the hafting system (the latter defined on experimental basis). This article therefore underlines the potential of combining different approaches to functional analysis associated with a ‘tailored’ reference collection and applying them to a high number of artefacts for reconstructing past human activities involving materials that are otherwise not preserved in these contexts. [1] Tomasso, S., Cnuts, D., Coppe, J., Geerts, F., Gils, M.V., Bie, M.D., Rots, V. (2021). A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pf3sm, ver 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. [2] De Bie, M., Van Gils, M. (2006). Les habitats des groupes à Federmesser (aziliens) dans le Nord de la Belgique. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 103, 781–790. [3] Coppe, J., Lepers, C., Clarenne, V., Delaunois, E., Pirlot, M. and Rots V. (2019). Ballistic Study Tackles Kinetic Energy Values of Palaeolithic Weaponry. Archaeometry, (61)4, 933-956. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12452 | A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide | Sonja Tomasso, Dries Cnuts, Justin Coppe, Marijn Van Gils, Ferdi Geerts, Marc De Bie, Veerle Rots | <p>The vast Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide, which is located in the Campine region (Northern Belgium), revealed the presence of numerous Final Palaeolithic concentrations situated on a large Late Glacial sand ridge on the northern edg... | Environmental archaeology, Landscape archaeology, Lithic technology, Traceology, Upper Palaeolithic | Marta Arzarello | 2021-09-14 17:04:38 | View | ||

24 Jun 2021

The strength of parthood ties. Modelling spatial units and fragmented objects with the TSAR method – Topological Study of Archaeological RefittingSébastien Plutniak https://osf.io/q2e69A practical computational approach to stratigraphic analysis using conjoinable material culture.Recommended by Hector A. Orengo based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper by Plutniak [1] presents a new method that uses refitting to help interpret stratigraphy using the topological distribution of conjoinable material culture. This new method opens up new avenues to the archaeological use of network analysis but also to assess the integrity of interpreted excavation layers. Beyond its evident applicability to standard excavation practice, the paper presents a series of characteristics that exemplify archaeological publication best practices and, as someone more versed in computational than in refitting studies I would like to comment upon. It was no easy task to find adequate reviewers for this paper as it combines techniques and expertise that are not commonly found together in individual researchers. However, Plutniak, with help from three reviewers, particularly M. Peeples, a leading figure in archaeological applications of network science, makes a considerable effort to be accessible to non-specialist archaeologists. The core Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting (TSAR) method is freely accessible as the R package archeofrag, which is available at the Comprehensive R Archive Network (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=archeofrag) that can be applied without the need to understand all its mathematical, graph theory and coding aspects. Beside these, an online interface including test data has been provided (https://analytics.huma-num.fr/Sebastien.Plutniak/archeofrag/), which aims to ease access to the method to those archaeologists inexperienced with R. Finally, supplementary material showing how to use the package and evaluating its potential through excellent examples is provided as both pdf and Rmw (Sweave) files. This is an important companion for the paper as it allows a better understanding of the methods presented in the paper and its practical application. The author shows particular care in testing the potential and capabilities of the method. For example, a function is provided “frag.observer.failure” to test the robustness of the edge count method against the TSAR method, which is able to prove that TSAR can deal well with incomplete information. As a further step in this direction both simulated and real field-acquired data are used to test the method which further proves that archeofrag is not only able to quantitatively assess the mixture of excavated layers but to propose meaningful alternatives, which no doubt will add an increased methodological consistency and thoroughness to previous quantitative approaches to material refitting work, even when dealing with very complex stratigraphies. All in all, this paper makes an important contribution to core archaeological practice through the use of innovative, reproducible and accessible computational methods. I fully endorse it for the conscious and solid methods it presents but also for its adherence to open publication practices. I hope that it can become of standard use in the reconstruction of excavated stratigraphical layers through conjoinable material culture.

[1] Plutniak, S. 2021. The Strength of Parthood Ties. Modelling Spatial Units and Fragmented Objects with the TSAR Method – Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting. OSF Preprints, q2e69, ver. 3 Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/q2e69. | The strength of parthood ties. Modelling spatial units and fragmented objects with the TSAR method – Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting | Sébastien Plutniak | <p>Refitting and conjoinable pieces have long been used in archaeology to assess the consistency of discrete spatial units, such as layers, and to evaluate disturbance and post-depositional processes. The majority of current methods, despite their... | Computational archaeology, Taphonomy | Hector A. Orengo | 2021-01-14 18:31:01 | View | ||

20 Jun 2020

Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32-28 ka cal. BP) in France.Anaïs Vignoles, William E. Banks, Laurent Klaric, Masa Kageyama, Marlon E. Cobos, Daniel Romero-Alvarez https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/ud3hjUnderstanding Palaeolithic adaptations through niche modelling - the case of the French Middle GravettianRecommended by Felix Riede based on reviews by Andreas Maier and João MarreirosThe paper entitled “Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32-28 ky cal. BP) in France” [1] submitted by A. Vignoles and colleagues offers a robust and interesting new analysis of the niche differences between the Rayssian and Noaillian facies of the Middle Gravettian in France. Understanding technological variability in the Palaeolithic is a long-standing challenge. Previous debates have vacillated between strong, quasi-ethnic culture-historical interpretations rooted in the traditional European school and extreme functional stances that would see artefact forms and their frequencies with assemblages conditioned by site function. While both positions have their merits, many empirical and conceptual caveats haunt them equally [see 2]. In this new study Vignoles and colleagues, so-called eco-cultural niche modelling is applied in an attempt to explore whether, and if so, which environmental background factors may have conditioned the emergence and persistence of two sub-cultural categories (facies) within the Middle Gravettian: the Rayssian and the Noaillian. These are are defined through, respectively, a specific knapping method and the presence of a specific burin type, and the occurrence of these seems divided by the Garonne River. Eco-cultural niche modelling has emerged as an archaeological application of distribution models widely employed in ecology, including palaeoecology, to understand organismal niche envelopes [3]. They constitute powerful tools for using the spatial and chronological information inherent in the archaeological record to up-scale interpretations of human-environment relations beyond individual site stratigraphies or dating series. Another important feature of such models is that their performance can, as Vignoles et al. also show, be formally evaluated and replicated. Following on from earlier applications of such techniques [e.g. 4], the authors here present an interesting study that uses very specific archaeological indicators – namely the Raysse method and the Noaillian burin – as defining features for the units (communities, traditions) whose adaptations they investigate. While broad tool types have previously been used as cultural taxonomic indicators in niche modelling studies [5], the present study is ambitious in its attempt to understand variability at a relatively small spatial scale. This mirrors equally interesting attempts of doing so in later prehistoric contexts [6]. Applications of niche modelling that use analytical units defined through archaeological characteristics (technology, typology) are opening up exciting new opportunities for pinning down precisely which environmental or climatic features these cultural components reference, if any. The study by Vignoles et al. makes a good case. At the same time, this approach also acutely raises questions of cultural taxonomy, of how we define our units of analysis and what they might mean [7]. It remains unclear to whether we can define such units on the basis of very different technological traits if the aim is to then use them as taxonomically equivalent in subsequent analyses. There is also a risk that these facies become reified as traditions of sub-cultures – then often further equated with specific people – through an overly normative view of their constituent technological elements. In addition, studies of adaptation in principle need to be conscious of the so-called ‘Galton’s Problem’, where the historical relatedness of the analytical units in question need to be taken into account in seeking salient correlations between cultural and environmental features [8]. In pushing forward eco-cultural niche modelling, the study by Vignoles et al. thus takes us some way forward in understanding the potentially adaptive variability within the Gravettian; future work should consider more strongly the specific historical relatedness amongst the cultural taxa under study and follow more theory-driven definition thereof. Such definition would also allow the post-analysis interpretations of eco-cultural niche modelling to be more explicit. Without doubt, the Gravettian as a whole – including, for instance, phenomena such as the Maisierian [9] – would benefit from additional and extended applications of this method. Similarly, other periods of the Palaeolithic also characterized by such variability (e.g. the Magdalenian and Final Palaeolithic) offer additional cases moving forward. Bibliography [1] Vignoles, A. et al. (2020). Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in 1 the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32-28 ky cal. BP) in France. PCI Archaeology. 10.31219/osf.io/ud3hj [2] Dibble, H.L., Holdaway, S.J., Lin, S.C., Braun, D.R., Douglass, M.J., Iovita, R., McPherron, S.P., Olszewski, D.I., Sandgathe, D., 2017. Major Fallacies Surrounding Stone Artifacts and Assemblages. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24, 813–851. 10.1007/s10816-016-9297-8 [3] Svenning, J.-C., Fløjgaard, C., Marske, K.A., Nógues-Bravo, D., Normand, S., 2011. Applications of species distribution modeling to paleobiology. Quaternary Science Reviews 30, 2930–2947. 10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.06.012 [4] Banks, W.E., d’Errico, F., Dibble, H.L., Krishtalka, L., West, D., Olszewski, D.I., Townsend Petersen, A., Anderson, D.G., Gillam, J.C., Montet-White, A., Crucifix, M., Marean, C.W., Sánchez-Goñi, M.F., Wolfarth, B., Vanhaeren, M., 2006. Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling: New Tools for Reconstructing the Geography and Ecology of Past Human Populations. PaleoAnthropology 2006, 68–83. [5] Banks, W.E., Zilhão, J., d’Errico, F., Kageyama, M., Sima, A., Ronchitelli, A., 2009. Investigating links between ecology and bifacial tool types in Western Europe during the Last Glacial Maximum. Journal of Archaeological Science 36, 2853–2867. 10.1016/j.jas.2009.09.014 [6] Whitford, B.R., 2019. Characterizing the cultural evolutionary process from eco-cultural niche models: niche construction during the Neolithic of the Struma River Valley (c. 6200–4900 BC). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11, 2181–2200. 10.1007/s12520-018-0667-x [7] Reynolds, N., Riede, F., 2019. House of cards: cultural taxonomy and the study of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Antiquity 93, 1350–1358. 10.15184/aqy.2019.49 [8] Mace, R., Pagel, M.D., 1994. The Comparative Method in Anthropology. Current Anthropology 35, 549–564. 10.1086/204317 [9] Pesesse, D., 2017. Is it still appropriate to talk about the Gravettian? Data from lithic industries in Western Europe. Quartär 64, 107–128. 10.7485/QU64_5 | Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32-28 ka cal. BP) in France. | Anaïs Vignoles, William E. Banks, Laurent Klaric, Masa Kageyama, Marlon E. Cobos, Daniel Romero-Alvarez | <p>The French Middle Gravettian represents an interesting case study for attempting to identify mechanisms behind the typo-technological variability observed in the archaeological record. Associated with the relatively cold and dry environments of... |  | Europe, Lithic technology, Paleoenvironment, Peopling, Upper Palaeolithic | Felix Riede | 2020-03-23 12:16:20 | View | |

02 May 2024

Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the MuseumAntonis G. Dimitriou, Stella Papadopoulou, Maria Dermenoudi, Angeliki Moneda, Vasiliki Drakaki, Andreana Malama, Alexandros Filotheou, Aristidis Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, Anastasios Tzitzis, Spyros Megalou, Stavroula Siachalou, Aggelos Bletsas, Traianos Yioultsis, Anna Maria Velentza, Sofia Pliasa, Nikolaos Fachantidis, Evangelia Tsangaraki, Dimitrios Karolidis, Charalampos Tsoungaris, Panagiota Balafa and Angeliki Koukouvou https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7805387Social Robotics in the Museum: a case for human-robot interaction using RFID TechnologyRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and Alexis PantosThe paper “Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum” (Dimitriou et al 2023) is a relevant contribution to museology and an interface between the public, archaeological discourse and the field of social robotics. It deals well with these themes and is concise in its approach, with a strong visual component that helps the reader to understand what is at stake. The option of demonstrating the different steps that lead to the final construction of the robot is appropriate, so that it is understood that it really is a linked process and not simple tasks that have no connection. The use of RFID technology for topological movement of social robots has been continuously developed (e.g., Corrales and Salichs 2009; Turcu and Turcu 2012; Sequeira and Gameiro 2017) and shown to have advantages for these environments. Especially in the context of a museum, with all the necessary precautions to avoid breaching the public's privacy, RFID labels are a viable, low-cost solution, as the authors point out (Dimitriou et al 2023), and, above all, one that does not require the identification of users. It is in itself part of an ambitious project, since the robot performs several functions and not just one, a development compared to other currents within social robotics (see Hellou et al 2022: 1770 for a description of the tasks given to robots in museums). The robotic system itself also makes effective use of the localization system, both physically, by RFID labels and by knowing how to situate itself with the public visiting the museum, adapting to their needs, which is essential for it to be successful (see Gasteiger, Hellou and Ahn 2022: 690 for the theme of localization). Archaeology can provide a threshold of approaches when it comes to social robotics and this project demonstrates that, bringing together elements of interaction, education and mobility in a single method. Hence, this is a paper with great merit and deserves to be recommended as it allows us to think of the museum as a space where humans and non-humans can converge to create intelligible discourses, whether in the historical, archaeological or cultural spheres. References Dimitriou, A. G., Papadopoulou, S., Dermenoudi, M., Moneda, A., Drakaki, V., Malama, A., Filotheou, A., Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, A., Tzitzis, A., Megalou, S., Siachalou, S., Bletsas, A., Yioultsis, T., Velentza, A. M., Pliasa, S., Fachantidis, N., Tsagkaraki, E., Karolidis, D., Tsoungaris, C., Balafa, P. and Koukouvou, A. (2024). Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum. Zenodo, 7805387, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7805387 Corrales, A. and Salichs, M.A. (2009). Integration of a RFID System in a Social Robot. In: Kim, JH., et al. Progress in Robotics. FIRA 2009. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 44. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03986-7_8 Gasteiger, N., Hellou, M. and Ahn, H.S. (2023). Factors for Personalization and Localization to Optimize Human–Robot Interaction: A Literature Review. Int J of Soc Robotics 15, 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-021-00811-8 Hellou, M., Lim, J., Gasteiger, N., Jang, M. and Ahn, H. (2022). Technical Methods for Social Robots in Museum Settings: An Overview of the Literature. Int J of Soc Robotics 14, 1767–1786 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-022-00904-y Sequeira, J. S., and Gameiro, D. (2017). A Probabilistic Approach to RFID-Based Localization for Human-Robot Interaction in Social Robotics. Electronics, 6(2), 32. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/electronics6020032 Turcu, C. and Turcu, C. (2012). The Social Internet of Things and the RFID-based robots. In: IV International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2012, pp. 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUMT.2012.6459769 | Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum | Antonis G. Dimitriou, Stella Papadopoulou, Maria Dermenoudi, Angeliki Moneda, Vasiliki Drakaki, Andreana Malama, Alexandros Filotheou, Aristidis Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, Anastasios Tzitzis, Spyros Megalou, Stavroula Siachalou, Aggelos Bletsas, ... | <p>This paper summarizes the adoption of new technologies in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece. RFID technology has been adopted. RFID tags have been attached to the artifacts. This allows for several interactions, including tracki... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Remote sensing | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-04-10 14:04:23 | View | |

19 Feb 2024

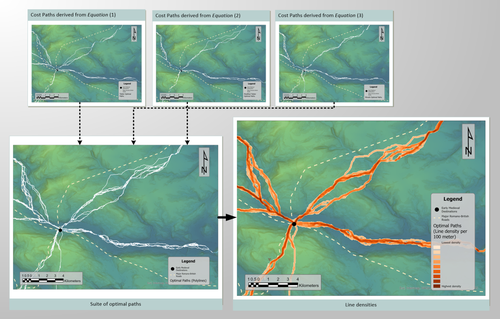

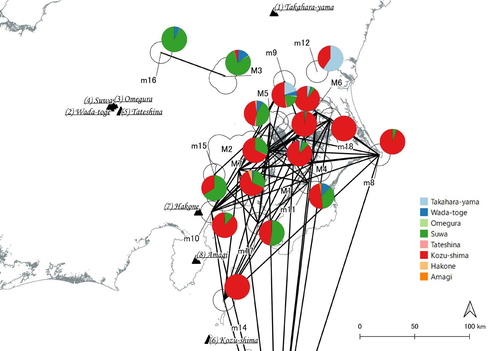

Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias ReductionFumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330Evaluating Methods for Reducing Sampling Bias in Network AnalysisRecommended by James Allison based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer

In a recent article, Fumihiro Sakahira and Hiro'omi Tsumura (2023) used social network analysis methods to analyze change in obsidian trade networks in Japan throughout the 13,000-year-long Jomon period. In the paper recommended here (Sakahira and Tsumura 2024), Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction they revisit that data and describe additional analyses that confirm the robustness of their social network analysis. The data, analysis methods, and substantive conclusions of the two papers overlap; what this new paper adds is a detailed examination of the data and methods, including use of bootstrap analysis to demonstrate the reasonableness of the methods they used to group sites into clusters. Both papers begin with a large dataset of approximately 21,000 artifacts from more than 250 sites dating to various times throughout the Jomon period. The number of sites and artifacts, varying sample sizes from the sites, as well as the length of the Jomon period, make interpretation of the data challenging. To help make the data easier to interpret and reduce problems with small sample sizes from some sites, the authors assign each site to one of five sub-periods, then define spatial clusters of sites within each period using the DBSCAN algorithm. Sites with at least three other sites within 10 km are joined into clusters, while sites that lack enough close neighbors are left as isolates. Clusters or isolated sites with sample sizes smaller than 30 were dropped, and the remaining sites and clusters became the nodes in the networks formed for each period, using cosine similarities of obsidian assemblages to define the strength of ties between clusters and sites. The main substantive result of Sakahira and Tsumura’s analysis is the demonstration that, during the Middle Jomon period (5500-4500 cal BP), clusters and isolated sites were much more connected than before or after that period. This is largely due to extensive distribution of obsidian from the Kozu-shima source, located on a small island off the Japanese mainland. Before the Middle Jomon period, Kozu-shima obsidian was mostly found at sites near the coast, but during the Middle Jomon, a trade network developed that took Kozu-shima obsidian far inland. This ended after the Middle Jomon period, and obsidian networks were less densely connected in the late and last Jomon periods. The methods and conclusions are all previously published (Sakahira and Tsumura 2023). What Sakahira and Tsumura add in Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction are: · an examination of the distribution of cosine similarities between their clusters for each period · a similar evaluation of the cosine similarities within each cluster (and among the unclustered sites) for each period · bootstrap analyses of the mean cosine similarities and network densities for each time period These additional analyses demonstrate that the methods used to cluster sites are reasonable, and that the use of spatially defined clusters as nodes (rather than the individual sites within the clusters) works well as a way of reducing bias from small, unrepresentative samples. An alternative way to reduce that bias would be to simply drop small assemblages, but that would mean ignoring data that could usefully contribute to the analysis. The cosine similarities between clusters show patterns that make sense given the results of the network analysis. The Middle Jomon period has, on average, the highest cosine similarities between clusters, and most cluster pairs have high cosine similarities, consistent with the densely connected, spatially expansive network from that time period. A few cluster pairs in the Middle Jomon have low similarities, apparently representing comparisons including one of the few nodes on the margins on the network that had little or no obsidian from the Kozu-shima source. The other four time periods all show lower average inter-cluster similarities and many cluster pairs have either high or low similarities. This probably reflects the tendency for nearby clusters to have very similar obsidian assemblages to each other and for geographically distant clusters to have dissimilar obsidian assemblages. The pattern is consistent with the less densely connected networks and regionalization shown in the network graphs. Thinking about this pattern makes me want to see a plot of the geographic distances between the clusters against the cosine similarities. There must be a very strong correlation, but it would be interesting to know whether there are any cluster pairs with similarities that deviate markedly from what would be predicted by their geographic separation. The similarities within clusters are also interesting. For each time period, almost every cluster has a higher average (mean and median) within-cluster similarity than the similarity for unclustered sites, with only two exceptions. This is partial validation of the method used for creating the spatial clusters; sites within the clusters are at least more similar to each other than unclustered sites are, suggesting that grouping them this way was reasonable. Although Sakahira and Tsumura say little about it, most clusters show quite a wide range of similarities between the site pairs they contain; average within-cluster similarities are relatively high, but many pairs of sites in most clusters appear to have low similarities (the individual values are not reported, but the pattern is clear in boxplots for the first four periods). There may be value in further exploring the occurrence of low site-to-site similarities within clusters. How often are they caused by small sample sizes? Clusters are retained in the analysis if they have a total of at least 30 artifacts, but clusters may contain sites with even smaller sample sizes, and small samples likely account for many of the low similarity values between sites in the same cluster. But is distance between sites in a cluster also a factor? If the most distant sites within a spatially extensive cluster are dissimilar, subdividing the cluster would likely improve the results. Further exploration of these within-cluster site-to-site similarity values might be worth doing, perhaps by plotting the similarities against the size of the smallest sample included in the comparison, as well as by plotting the cosine similarity against the distance between sites. Any low similarity values not attributable to small sample sizes or geographic distance would surely be worth investigating further. Sakahira and Tsumura also use a bootstrap analysis to simulate, for each time period, mean cosine similarities between clusters and between site pairs without clustering. They also simulate the network density for each time period before and after clustering. These analyses show that, almost always, mean simulated cosine similarities and mean simulated network density are higher after clustering than before. The simulated mean values also match the actual mean values better after clustering than before. This improved match to actual values when the sites are clustered for the bootstrap reinforces the argument that clustering the sites for the network analysis was a reasonable result. The strength of this paper is that Sakahira and Tsumura return to reevaluate their previously published work, which demonstrated strong patterns through time in the nature and extent of Jomon obsidian trade networks. In the current paper they present further analyses demonstrating that several of their methodological decisions were reasonable and their results are robust. The specific clusters formed with the DBSCAN algorithm may or may not be optimal (which would be unreasonable to expect), but the authors present analyses showing that using spatial clusters does improve their network analysis. Clustering reduces problems with small sample sizes from individual sites and simplifies the network graphs by reducing the number of nodes, which makes the results easier to interpret. Reference Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2023). Tipping Points of Ancient Japanese Jomon Trade Networks from Social Network Analyses of Obsidian Artifacts. Frontiers in Physics 10:1015870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.1015870 Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2024). Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction, Zenodo, 10057602, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330 | Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction | Fumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura | <p>This study aims to investigate the dynamics of obsidian trade networks during the Jomon period (approximately 15,000 to 2,400 years ago), the hunting and gathering era in Japan. To improve regional representation and reduce the distortions caus... |  | Asia, Computational archaeology | James Allison | Thegn Ladefoged, Matthew Peeples | 2023-05-28 05:51:12 | View |

25 Jul 2023

Sorghum and finger millet cultivation during the Aksumite period: insights from ethnoarchaeological modelling and microbotanical analysisAbel Ruiz-Giralt, Alemseged Beldados, Stefano Biagetti, Francesca D’Agostini, A. Catherine D’Andrea, Yemane Meresa, Carla Lancelotti https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7859673An innovative integration of ethnoarchaeological models with phytolith data to study histories of C4 crop cultivationRecommended by Emma Loftus based on reviews by Tanya Hattingh and 1 anonymous reviewerThis article “Sorghum and finger millet cultivation during the Aksumite period: insights from ethnoarchaeological modelling and microbotanical analysis”, submitted by Ruiz-Giralt and colleagues (2023a), presents an innovative attempt to address the lack of palaeobotanical data concerning ancient agricultural strategies in the northern Horn of Africa. In lieu of well-preserved macrobotanical remains, an especial problem for C4 crop species, these authors leverage microbotanical remains (phytoliths), in combination with ethnoarchaeologically-informed agroecology models to investigate finger millet and sorghum cultivation during the period of the Aksumite Kingdom (c. 50 BCE – 800 CE). Both finger millet and sorghum have played important roles in the subsistence of the Horn region, and throughout much of the rest of Africa and the world in the past. The importance of these drought-resistant and adaptable crops is likely to increase as we move into a warmer, drier world. Yet their histories of cultivation are still only approximately sketched due to a paucity of well-preserved remains from archaeological sites - for example, debate continues as to the precise centre of their domestication. Recent studies of phytoliths (by these and other authors) are demonstrating the likely continuous presence of these crops from the pre-Aksumite period. However, phytoliths are diagnostic only to broad taxonomic levels, and cannot be used to securely identify species. To supplement these observations, Ruiz-Giralt et al. deploy models (previously developed by this team: Ruiz-Giralt et al., 2023b) that incorporate environmental variables and ethnographic data on traditional agrosystems. They evaluate the feasibility of different agricultural regimes around the locations of numerous archaeological sites distributed across the highlands of northern Ethiopia and southern Eritrea. Their results indicate the general viability of finger millet and sorghum cultivation around archaeological settlements in the past, with various regions displaying greater-or-lesser suitability at different distances from the site itself. The models also highlight the likelihood of farmers utilising extensive-rainfed regimes, given low water and soil nutrient requirements for these crops. The authors discuss the results with respect to data on phytolith assemblages, particularly at the site of Ona Adi. They conclude that Aksumite agriculture very likely included the cultivation of finger millet and sorghum, as part of a broader system of rainfed cereal cultivation. Ruiz-Giralt et al. argue, and have demonstrated, that ethnoarchaeologically-informed models can be used to generate hypotheses to be evaluated against archaeological data. The integration of many diverse lines of information in this paper certainly enriches the discussion of agricultural possibilities in the past, and the use of a modelling framework helps to formalise the available hypotheses. However, they emphasise that modelling approaches cannot be pursued in lieu of rigorous archaeobotanical studies but only in tandem - a greater commitment to archaeobotanical sampling is required in the region if we are to fully detail the histories of these important crops. References Ruiz-Giralt, A., Beldados, A., Biagetti, S., D’Agostini, F., D’Andrea, A. C., Meresa, Y. and Lancelotti, C. (2023a). Sorghum and finger millet cultivation during the Aksumite period: insights from ethnoarchaeological modelling and microbotanical analysis. Zenodo, 7859673, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7859673 Ruiz-Giralt, A., Biagetti, S., Madella, M. and Lancelotti, C. (2023b). Small-scale farming in drylands: New models for resilient practices of millet and sorghum cultivation. PLoS ONE 18, e0268120. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268120

| Sorghum and finger millet cultivation during the Aksumite period: insights from ethnoarchaeological modelling and microbotanical analysis | Abel Ruiz-Giralt, Alemseged Beldados, Stefano Biagetti, Francesca D’Agostini, A. Catherine D’Andrea, Yemane Meresa, Carla Lancelotti | <p>For centuries, finger millet (<em>Eleusine coracana</em> Gaertn.) and sorghum (<em>Sorghum bicolor</em> (L.) Moench) have been two of the most economically important staple crops in the northern Horn of Africa. Nonetheless, their agricultural h... | Africa, Archaeobotany, Computational archaeology, Protohistory, Spatial analysis | Emma Loftus | 2023-04-29 16:24:54 | View | ||

20 Feb 2024

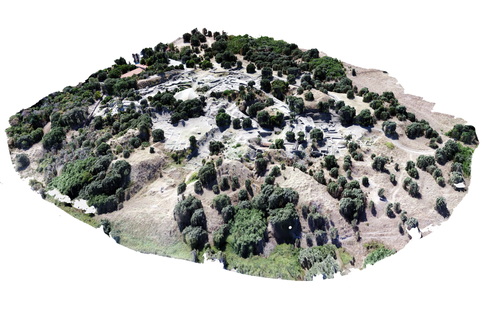

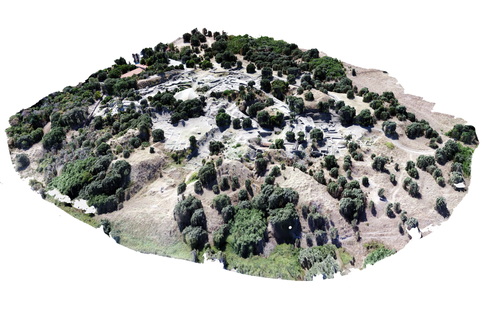

Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of ArchaeologyWaagen, Jitte & Wijngaarden, Gert Jan van https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10061343Rewriting Archaeological Narratives: Archaeology of Archaeology through 3D Site Topography RecordingRecommended by Devi Taelman based on reviews by Geert Verhoeven, Jesús García-Sánchez and Catherine Scott based on reviews by Geert Verhoeven, Jesús García-Sánchez and Catherine Scott

Even though applications of 3D recording have existed in archaeology for a long time, it is only since the early 2000s that this field of research has become mainstream thanks to technological advances, and the availability of low-cost sensors and image-based modelling software. This has led to significant changes in the way archaeological sites are documented. This paper entitled "Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology" by Jitte Waagen & Gert Jan van Wijngaarden (2024) presents an overview of the current developments in the application possibilities of 3D site topography recording in archaeology. The paper is the result of the round table discussion "Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology" at the CAA conference on 5 April 2023 in Amsterdam, with contributions from Radu Brunchi, Nicola Lercari, Joep Orbons, Davide Tanasi, Alicia Walsh, Pawel Wolf and Teagan Zoldoske. The paper starts with a discussion of the Amsterdam Troy Project (ATP). In the frame of the ATP, the rich history of archaeological activity (over 150 years of fieldwork) at Troy is being studied to explore how previous archaeological research has helped to shape the current topography of the site and how these earlier research activities, embedded in their contemporary theoretical frameworks, have determined our understanding of the site (see Murray and M. Spriggs 2017, Carver 2011 for the influence of theory on archaeological fieldwork and archaeology as a discipline), the so-called 'Archaeology of Archaeology' approach. In addition to studying previous research records and re-excavating old excavation trenches, a central element of the project is the 3D recording of the past and present topography of the site in order to reconstruct the archaeological research activities at the site and their impact on the archaeological landscape. The paper focuses on current trends in 3D recording of archaeological site topography and discusses three main areas where 3D recording of archaeological site topography can contribute to the "Archaeology of Archaeology" approach: (1) monitoring the topography of sites for preservation, conservation, research and dissemination purposes; (2) reconstructing, reevaluating and reinterpreting past archaeological research efforts; and (3) archiving in a 4D (GIS) environment. This is done using the example of the Amsterdam Troy project and comparing it with other projects using similar methods and approaches. Using these case studies, the authors effectively discuss the impact of these technologies on the understanding of the topography of archaeological sites and how 3D recording can enhance archaeological research methodologies and interpretations, for example, by not using such 3D approaches as a stand-alone product but integrating them with available information from previous research activities. They also recognise the limitations and challenges involved, such as the need for customised data acquisition strategies and the lack of ready-made software solutions for developing comprehensive data management strategies. One topic that could have been covered in more detail is how 3D site topography recording (and 3D recording in general) is affected by current theoretical developments in archaeology. Like any other archaeological fieldwork or data collection approach, it is a child of its time. Decisions such as what to record, how to record, what to store, how to store, what to visualise, and how to visualise influence our understanding of archaeological sites (Ward 2022). This minor critical reflection aside, the paper makes a timely and significant contribution to archaeology by addressing current trends and the limitations of the increasingly widespread use of 3D site topography recording technologies. References Carver, G. (2011). Reflections on the archaeology of archaeological excavation, Archaeological Dialogues 18(1), pp. 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203811000067 Murray, T. and Spriggs, M. (2017). The historiography of archaeology: exploring theory, contingency and rationality, World Archaeology 49(2), pp. 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2017.1334583 Ward, C. (2022). Excavating the Archive / Archiving the Excavation: Archival Processes and Contexts in Archaeology, Advances in Archaeological Practice 10(2), pp. 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2022.1 Waagen, J. and van Wijngaarden, G.J. (2024). Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology, Zenodo, 10061343, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommonded by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10061343 | Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology | Waagen, Jitte & Wijngaarden, Gert Jan van | <p>The current ubiquitous use of 3D recording technologies in archaeological fieldwork, for a large part due to the application of budget-friendly (drone) sensors and the availability of many low-cost image-based 3D modelling software packages, ha... |  | Computational archaeology, Remote sensing | Devi Taelman | 2023-10-17 23:03:47 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer