Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▼ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

03 Nov 2023

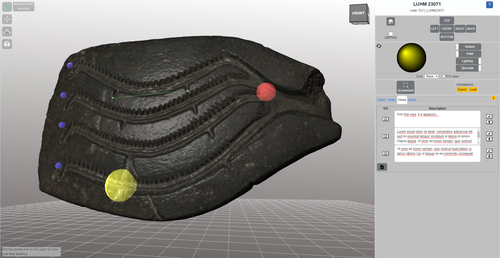

The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep InteractionMarco Callieri, Åsa Berggren, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Paola Derudas, Domenica Dininno, Fredrik Ekengren, Giuseppe Naponiello https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10067103A comparative teaching and learning tool for 3D data: Dynamic CollectionsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Louise Tharandt based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Louise Tharandt

The paper (Callieri, M. et al. 2023) describes the “Dynamic Collections” project, an online platform initially created to showcase digital archaeological collections of Lund University. During a phase of testing by department members, new functionalities and artefacts were added resulting in an interactive platform adapted to university-level teaching and learning. The paper introduces into the topic and related works after which it starts to explain the project itself. The idea is to resemble the possibilities of interaction of non-digital collections in an online platform. Besides the objects themselves, the online platform offers annotations, measurement and other interactive tools based on the already known 3DHOP framework. With the possibility to create custom online collections a collaborative working/teaching environment can be created. The already wide-spread use of the 3DHOP framework enabled the authors to develop some functionalities that could be used in the “Dynamic Collections” project. Also, current and future plans of the project are discussed and will include multiple 3D models for one object or permanent identifiers, which are both important additions to the system. The paper then continues to explain some of its further planned improvements, like comparisons and support for teaching, which will make the tool an important asset for future university-level education. The paper in general is well-written and informative and introduces into the interactive tool, that is already available and working. It is very positive, that the authors rely on up-to-date methodologies in creating 3D online repositories and are in fact improving them by testing the tool in a teaching environment. They mention several times the alignment with upcoming EU efforts related to the European Collaborative Cloud for Cultural Heritage (ECCCH), which is anticipatory and far-sighted and adds to the longevity of the project. Comments of the reviewers were reasonably implemented and led to a clearer and more concise paper. I am very confident that this tool will find good use in heritage research and presentation as well as in university-level teaching and learning. Although the authors never answer the introductory question explicitly (What characteristics should a virtual environment have in order to trigger dynamic interaction?), the paper gives the implicit answer by showing what the "Dynamic Collections" project has achieved and is able to achieve in the future. BibliographyCallieri, M., Berggren, Å., Dell'Unto, N., Derudas, P., Dininno, D., Ekengren, F., and Naponiello, G. (2023). The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep Interaction, Zenodo, 10067103, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10067103 | The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep Interaction | Marco Callieri, Åsa Berggren, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Paola Derudas, Domenica Dininno, Fredrik Ekengren, Giuseppe Naponiello | <p>The Dynamic Collections project is an ongoing initiative pursued by the Visual Computing Lab ISTI-CNR in Italy and the Lund University Digital Archaeology Laboratory-DARKLab, Sweden. The aim of this project is to explore the possibilities offer... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-31 15:05:32 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3DFlorian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269A valuable contribution to automated analysis of palaeolithic artefactsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper (Linsel/Bullenkamp/Mara 2024), the authors propose an automatic system for scar-ridge-pattern detection on palaeolithic artefacts based on Morse Theory. Scare-Ridge pattern recognition is a process that is usually done manually while creating a drawing of the object itself. Automatic systems to detect scars or ridges exist, but only a small amount of them is utilizing 3D data. In addition to the scar-ridges detection, the authors also experiment in automatically detecting the operational sequence, the temporal relation between scars and ridges. As a result, they can export a traditional drawing as well as graph models displaying the relationships between the scars and ridges. After an introduction to the project and the practice of documenting palaeolithic artefacts, the authors explain their procedure in automatising the analysis of scars and ridges as well as their temporal relation to each other on these artefacts. To illustrate the process, an open dataset of lithic artefacts from the Grotta di Fumane, Italy, was used and 62 artefacts selected. To establish a Ground Truth, the artefacts were first annotated manually. The authors then continue to explain in detail each step of the automated process that follows and the results obtained. In the second part of the paper, the results are presented. First the results of the segmentation process shows that the average percentage of correctly labelled vertices is over 91%, which is a remarkable result. The graph modelling however shows some more difficulties, which the authors are aware of. To enhance the process, the authors rightfully aim to include datasets of experimental archaeology in the future. They also aim to develop a way of detecting the operational sequence automatically and precisely. This paper has great potential as it showcases exactly what Digital and Computational Archaeology is about: The development of new digital methods to enhance the analysis of archaeological data. While this procedure is still in development, the authors were able to present a valuable contribution to the automatization of analytical archaeology. By creating a step towards the machine-readability of this data, they also open up the way to further steps in machine learning within Archaeology. BibliographyLinsel, F., Bullenkamp, J. P., and Mara, H. (2024). Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D, Zenodo, 8296269, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269 | Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D | Florian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara | <p>Motivated by the concept of combining the archaeological practice of creating lithic artifact drawings with the potential of 3D mesh data, our goal in this project is not only to analyze the shape at the artifact level, but also to enable a mor... | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Upper Palaeolithic | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-09-01 23:03:59 | View | ||

16 May 2022

Wood technology: a Glossary and Code for analysis of archaeological wood from stone tool culturesAnnemieke Milks, Jens Lehmann, Utz Böhner, Dirk Leder, Tim Koddenberg, Michael Sietz, Matthias Vogel, Thomas Terberger https://osf.io/x8m4jOpen glossary for wood technologiesRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Paloma Vidal-Matutano, Oriol López-Bultó, Eva Francesca Martellotta and Laura Caruso Fermé based on reviews by Paloma Vidal-Matutano, Oriol López-Bultó, Eva Francesca Martellotta and Laura Caruso Fermé

Wood is a widely available and versatile material, so it is not surprising that it has been a key resource throughout human history. However, it is more vulnerable to decomposition than other materials, and its direct use is only rarely recorded in prehistoric sites. Despite this, there are exceptions (e.g., [1-5] [6] and references therein), and indirect evidence of its use has been attested through use-wear analyses, residue analyses (e.g., [7]) and imprints on the ground (e.g., [8]). One interesting finding of note is that the technology required to make, for example, wooden spears was quite complex [9], leading some authors to propose that this type of tool production represented a cognitive leap for Pleistocene hominids [10]. Other researchers, however, have proposed that the production process for wooden tools could have been much easier than is currently thought [11]. Be that as it may, in recent years researchers have begun to approach wood remains systematically, developing analyses of natural and anthropogenic damage, often with the help of experimental reference samples. In this work, the authors elaborate a comprehensive glossary as a first step towards the understanding of the use of wood for technological purposes in different times and places, as there is still a general gap in the established nomenclature. Thus, this glossary is a synthesis and standardisation of analytical terms for early wood technologies that includes clear definitions and descriptions of traces from stone tool-using cultures, to avoid confusion in ongoing and future studies of wood tools. For this, the authors have carried out a detailed search of the current literature to select appropriate terms associated with additional readings that provide a wide, state-of-the-art description of the field of wood technology. An interesting point is that the glossary has been organised within a chaîne opératoire framework divided into categories including general terms and natural traces, and then complemented by an appendix of images. It is important to define the natural traces –understanding these as alterations caused by natural processes–because they can mask those modifications produced by other agents affecting both unmodified and modified wood before, during or after its human use. In short, the work carried out by Milks et al. [6] is an excellent and complete assessment and vital to the technological approach to wooden artifacts from archaeological contexts and establishing a common point for a standardised nomenclature. One of its particular strengths is that the glossary is a preprint that will remain open during the coming years, so that other researchers can continue to make suggestions and refinements to improve the definitions, terms and citations within it. [1] Oakley, K., Andrews, P., Keeley, L., Clark, J. (1977). A reappraisal of the Clacton spearpoint. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 43, 13-30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00010343 [2] Thieme, H. (1997). Lower Palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany. Nature 385, 807-810. https://doi.org/10.1038/385807a0 [3] Schoch, W.H., Bigga, G., Böhner, U., Richter, P., Terberger, T. (2015). New insights on the wooden weapons from the Paleolithic site of Schöningen. Journal of Human Evolution 89, 214-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.08.004 [4] Aranguren, B., Revedin, A., Amico, N., Cavulli, F., Giachi, G., Grimaldi, S. et al. (2018). Wooden tools and fire technology in the early Neanderthal site of Poggetti Vecchi (Italy). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115, 2054-2059. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1716068115 [5] Rios-Garaizar, J., López-Bultó, O., Iriarte, E., Pérez-Garrido, C., Piqué, R., Aranburu, A., et al. (2018). A Middle Palaeolithic wooden digging stick from Aranbaltza III, Spain. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0195044. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195044 [6] Milks, A. G., Lehmann, J., Böhner, U., Leder, D., Koddenberg, T., Sietz, M., Vogel, M., Terberger, T. (2022). Wood technology: a Glossary and Code for analysis of archaeological wood from stone tool cultures. Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/x8m4j [7] Nugent, S. (2006). Applying use-wear and residue analyses to digging sticks. Mem Qld Mus Cult Herit Ser 4, 89-105. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.890092331962439 [8] Allué, E., Cabanes, D., Solé, A., Sala, R. (2012). Hearth Functioning and Forest Resource Exploitation Based on the Archeobotanical Assemblage from Level J, in: i Roura E. (Ed.), High Resolution Archaeology and Neanderthal Behavior: Time and Space in Level J of Abric Romaní (Capellades, Spain). Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp. 373-385. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3922-2_9 [9] Ennos, A.R., Chan, T.L. (2016). "Fire hardening" spear wood does slightly harden it, but makes it much weaker and more brittle. Biology Letters 12. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0174 [10] Haidle, M.N. (2009). How to think a simple spear?, in: de Beaune S.A., Coolidge F.L., Wynn T. (Eds.), Cognitive Archaeology and Human Evolution. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 57-73. [11] Garofoli, D. (2015). A Radical Embodied Approach to Lower Palaeolithic Spear-making. Journal of Mind and Behavior 36, 1-26. | Wood technology: a Glossary and Code for analysis of archaeological wood from stone tool cultures | Annemieke Milks, Jens Lehmann, Utz Böhner, Dirk Leder, Tim Koddenberg, Michael Sietz, Matthias Vogel, Thomas Terberger | <p>The analysis of wood technologies created by stone tool-using cultures remains underdeveloped relative to the study of lithic and bone technologies. In recent years archaeologists have begun to approach wood assemblages systematically, developi... |  | Ancient Palaeolithic, Archaeobotany, Mesolithic, Middle Palaeolithic, Neolithic, Raw materials, Taphonomy, Traceology, Upper Palaeolithic | Ruth Blasco | 2021-12-01 12:18:53 | View | |

20 Jul 2022

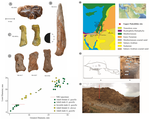

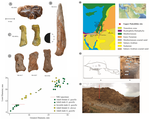

Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, IsraelNimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4New zooarchaeological data from the Upper Palaeolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2, IsraelRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio

The Levantine Corridor is considered a crossing point to Eurasia and one of the main areas for detecting population flows (and their associated cultural and economic changes) during the Pleistocene. This area could have been closed during the most arid periods, giving rise to processes of population isolation between Africa and Eurasia and intermittent contact between Eurasian human communities [1,2]. Zooarchaeological studies of the early Upper Palaeolithic assemblages constitute an important source of knowledge about human subsistence, making them central to the debate on modern behaviour. The Early Upper Palaeolithic sequence in the Levant includes two cultural entities – the Early Ahmarian and the Levantine Aurignacian. This latter is dated to 39-33 ka and is considered a local adaptation of the European Aurignacian techno-complex. In this work, the authors present a zooarchaeological study of the Nahal Rahaf 2 (ca. 35 ka) archaeological site in the southern Judean Desert in Israel [3]. Zooarchaeological data from the early Upper Paleolithic desert regions of the southern Levant are not common due to preservation problems of non-lithic finds. In the case of Nahal Rahaf 2, recent excavation seasons brought to light a stratigraphical sequence composed of very well-preserved archaeological surfaces attributed to the 'Arkov-Divshon' cultural entity, which is associated with the Levantine Aurignacian. This study shows age-specific caprine (Capra cf. Capra ibex) hunting on prime adults and a generalized procurement of gazelles (Gazella cf. Gazella gazella), which seem to have been selectively transported to the site and processed for within-bone nutrients. An interesting point to note is that the proportion of goats increases along the stratigraphic sequence, which suggests to the authors a specialization in the economy over time that is inversely related to the occupational intensity of use of the site. It is also noteworthy that the materials represent a large sample compared to previous studies from the Upper Paleolithic of the Judean Desert and Negev. In summary, this manuscript contributes significantly to the study of both the palaeoenvironment and human subsistence strategies in the Upper Palaeolithic and provides another important reference point for evaluating human hunting adaptations in the arid regions of the southern Levant. References [1] Bermúdez de Castro, J.-L., Martinon-Torres, M. (2013). A new model for the evolution of the human pleistocene populations of Europe. Quaternary Int. 295, 102-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.036 [2] Bar-Yosef, O., Belfer-Cohen, A. (2010). The Levantine Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic. In Garcea, E.A.A. (Ed), South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples Between 130,000 and 10,000 Years Ago. Oxbow Books, pp. 144-167. [3] Marom, N., Gnezdilov, D. L., Shafir, R., Barzilai, O. and Shemer, M. (2022). Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel. BioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492258, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4 | Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel | Nimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer | <p>Nahal Rahaf 2 (NR2) is an Early Upper Paleolithic (ca. 35 kya) rock shelter in the southern Judean Desert in Israel. Two excavation seasons in 2019 and 2020 revealed a stratigraphical sequence composed of intact archaeological surfaces attribut... |  | Upper Palaeolithic, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Joana Gabucio | 2022-05-19 06:16:47 | View |

01 Sep 2023

Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854))Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552A zooarchaeological perspective on testudine bones from Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Southeast AsiaRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta

The study of the evolution of the human diet has been a central theme in numerous archaeological and paleoanthropological investigations. By reconstructing diets, researchers gain deeper insights into how humans adapted to their environments. The analysis of animal bones plays a crucial role in extracting dietary information. Most studies involving ancient diets rely heavily on zooarchaeological examinations, which, due to their extensive history, have amassed a wealth of data. During the Pleistocene–Holocene periods, testudine bones have been commonly found in a multitude of sites. The use of turtles and tortoises as food sources appears to stretch back to the Early Pleistocene [1-4]. More importantly, these small animals play a more significant role within a broader debate. The exploitation of tortoises in the Mediterranean Basin has been examined through the lens of optimal foraging theory and diet breadth models (e.g. [5-10]). According to the diet breadth model, resources are incorporated into diets based on their ranking and influenced by factors such as net return, which in turn depends on caloric value and search/handling costs [11]. Within these theoretical frameworks, tortoises hold a significant position. Their small size and sluggish movement require minimal effort and relatively simple technology for procurement and processing. This aligns with optimal foraging models in which the low handling costs of slow-moving prey compensate for their small size [5-6,9]. Tortoises also offer distinct advantages. They can be easily transported and kept alive, thereby maintaining freshness for deferred consumption [12-14]. For example, historical accounts suggest that Mexican traders recognised tortoises as portable and storable sources of protein and water [15]. Furthermore, tortoises provide non-edible resources, such as shells, which can serve as containers. This possibility has been discussed in the context of Kebara Cave [16] and noted in ethnographic and historical records (e.g. [12]). However, despite these advantages, their slow growth rate might have rendered intensive long-term predation unsustainable. While tortoises are well-documented in the Southeast Asian archaeological record, zooarchaeological analyses in this region have been limited, particularly concerning prehistoric hunter-gatherer populations that may have relied extensively on inland chelonian taxa. With the present paper Bochaton et al. [17] aim to bridge this gap by conducting an exhaustive zooarchaeological analysis of turtle bone specimens from four Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Thailand and Cambodia. These assemblages span from the Late Pleistocene to the first half of the Holocene. The authors focus on bones attributed to the yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata), which is the most prevalent taxon in the assemblages. The research include osteometric equations to estimate carapace size and explore population structures across various sites. The objective is to uncover human tortoise exploitation strategies in the region, and the results reveal consistent subsistence behaviours across diverse locations, even amidst varying environmental conditions. These final proposals suggest the possibility of cultural similarities across different periods and regions in continental Southeast Asia. In summary, this paper [17] represents a significant advancement in the realm of zooarchaeological investigations of small prey within prehistoric communities in the region. While certain approaches and issues may require further refinement, they serve as a comprehensive and commendable foundation for assessing human hunting adaptations.

References [1] Hartman, G., 2004. Long-term continuity of a freshwater turtle (Mauremys caspica rivulata) population in the northern Jordan Valley and its paleoenvironmental implications. In: Goren-Inbar, N., Speth, J.D. (Eds.), Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 61-74. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dtct.11 [2] Alperson-Afil, N., Sharon, G., Kislev, M., Melamed, Y., Zohar, I., Ashkenazi, R., Biton, R., Werker, E., Hartman, G., Feibel, C., Goren-Inbar, N., 2009. Spatial organization of hominin activities at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. Science 326, 1677-1680. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180695 [3] Archer, W., Braun, D.R., Harris, J.W., McCoy, J.T., Richmond, B.G., 2014. Early Pleistocene aquatic resource use in the Turkana Basin. J. Hum. Evol. 77, 74-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.02.012 [4] Blasco, R., Blain, H.A., Rosell, J., Carlos, D.J., Huguet, R., Rodríguez, J., Arsuaga, J.L., Bermúdez de Castro, J.M., Carbonell, E., 2011. Earliest evidence for human consumption of tortoises in the European Early Pleistocene from Sima del Elefante, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain. J. Hum. Evol. 11, 265-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.06.002 [5] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N., Surovell, T.A., Tchernov, E., Bar-Yosef, O., 1999. Palaeolithic growth pulses evidenced by small animal exploitation. Science 283, 190-194. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5399.190 [6] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., Surovell, T.A., 2000. The tortoise and the hare: small-game use, the Broad-Spectrum Revolution, and paleolithic demography. Curr. Anthropol. 41, 39-73. https://doi.org/10.1086/300102 [7] Stiner, M.C., 2001. Thirty years on the “Broad Spectrum Revolution” and paleolithic demography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 (13), 6993-6996. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.121176198 [8] Stiner, M.C., 2005. The Faunas of Hayonim Cave (Israel): a 200,000-Year Record of Paleolithic Diet. Demography and Society. American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 48. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge. [9] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., 2002. Approaches to prehistoric diet breadth, demography, and prey ranking systems in time and space. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 9, 181-214. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016530308865 [10] Blasco, R., Cochard, D., Colonese, A.C., Laroulandie, V., Meier, J., Morin, E., Rufà, A., Tassoni, L., Thompson, J.C. 2022. Small animal use by Neanderthals. In Romagnoli, F., Rivals, F., Benazzi, S. (eds.), Updating Neanderthals: Understanding Behavioral Complexity in the Late Middle Palaeolithic. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 123-143. ISBN 978-0-12-821428-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2019-0-03240-2 [11] Winterhalder, B., Smith, E.A., 2000. Analyzing adaptive strategies: human behavioural ecology at twenty-five. Evol. Anthropol. 9, 51-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(2000)9:2%3C51::aid-evan1%3E3.0.co;2-7 [12] Schneider, J.S., Everson, G.D., 1989. The Desert Tortoise (Xerobates agassizii) in the Prehistory of the Southwestern Great Basin and Adjacent areas. J. Calif. Gt. Basin Anthropol. 11, 175-202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825383 [13] Thompson, J.C., Henshilwood, C.S., 2014b. Nutritional values of tortoises relative to ungulates from the Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa: implications for foraging and social behaviour. J. Hum. Evol. 67, 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.010 [14] Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Smith, K.T., Maul, L.Ch., Sañudo, P., Barkai, R., Gopher, A. 2016. Tortoises as a Dietary Supplement: a view from the Middle Pleistocene site of Qesem Cave, Israel. Quat Sci Rev 133, 165-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.12.006 [15] Pepper, C., 1963. The truth about the tortoise. Desert Mag. 26, 10-11. [16] Speth, J.D., Tchernov, E., 2002. Middle Paleolithic tortoise use at Kebara Cave (Israel). J. Archaeol. Sci. 29, 471-483. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2001.0740 [17] Bochaton, C., Chantasri, S., Maneechote, M., Claude, J., Griggo, C., Naksri, W., Forestier, H., Sophady, H., Auertrakulvit, P., Bowonsachoti, J. and Zeitoun, V. (2023) Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed Tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854)), BioRXiv, 2023.04.27.538552 , ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552v3 | Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (*Indotestudo elongata* (Blyth, 1854)) | Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun | <p style="text-align: justify;">While non-marine turtles are almost ubiquitous in the archaeological record of Southeast Asia, their zooarchaeological examination has been inadequately pursued within this tropical region. This gap in research hind... |  | Asia, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Iratxe Boneta, Noel Amano | 2023-05-02 09:30:50 | View |

02 Mar 2024

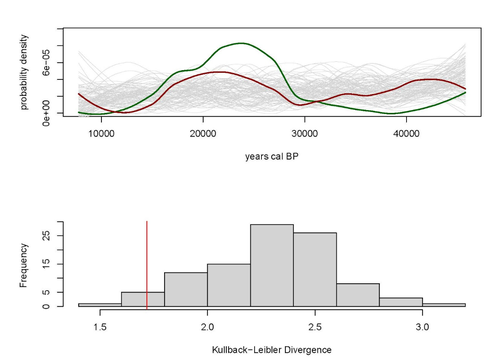

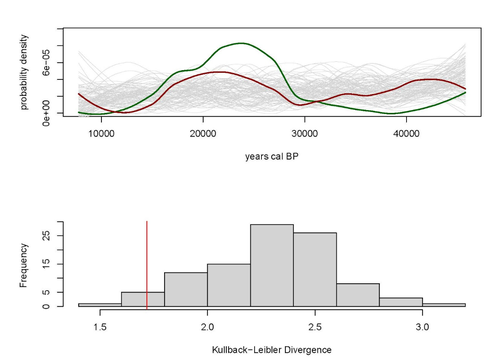

A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasetsNimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733A new approach to Predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer

Various biological systems have been subjected to mathematical modelling to enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions among different species. Among these models, the predator-prey model holds a significant position. Its relevance stems not only from its application in biology, where it largely governs the coexistence of diverse species in open ecosystems, but also from its utility in other domains. Predator-prey dynamics have long been a focal point in population ecology, yet access to real-world data is confined to relatively brief periods, typically less than a century. Studying predator-prey dynamics over extended periods presents challenges due to the limited availability of population data spanning more than a century. The most extensive dataset is the hare-lynx records from the Hudson Bay Company, documenting a century of fur trade [1]. However, other records are considerably shorter, usually spanning decades [2,3]. This constraint hampers our capacity to investigate predator-prey interactions over centennial or millennial scales. Marom and Wolkowski [4] propose here that leveraging regional radiocarbon databases offers a solution to this challenge, enabling the reconstruction of predator-prey population dynamics over extensive timeframes. To substantiate this proposition, they draw upon examples from Pleistocene Beringia and the Holocene Judean Desert. This approach is highly relevant and might provide insight into ecological processes occurring at a time scale beyond the limits of current ecological datasets. The methodological approach employed in this article proposes that the summed probability distribution (SPD) of predator radiocarbon dates, which reflects changes in population size, will demonstrate either more or less variation than anticipated from random sampling in a homogeneous distribution spanning the same timeframe. A deviation from randomness would imply a covariation between predator and prey populations. This basic hypothesis makes no assumptions about the frequency, mechanism, or cause of predator-prey interactions, as it is assumed that such aspects cannot be adequately tested with the available data. If validated, this hypothesis would offer initial support for the idea that long-term regional radiocarbon data contain signals of predator-prey interactions. This approach could justify the construction of larger datasets to facilitate a more comprehensive exploration of these signal structures.

References [1] Elton, C. and Nicholson, M., 1942. The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada. J. Anim. Ecol. 11, 215–244. [2] Gilg, O., Sittler, B. and Hanski, I., 2009. Climate change and cyclic predator-prey population dynamics in the high Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01927.x [3] Vucetich, J.A., Hebblewhite, M., Smith, D.W. and Peterson, R.O., 2011. Predicting prey population dynamics from kill rate, predation rate and predator-prey ratios in three wolf-ungulate systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01855.x [4] Marom, N. and Wolkowski, U. (2024). A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets, BioRxiv, 566733, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733 | A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets | Nimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski | <p>Predator-prey interactions have been a central theme in population ecology for the past century, but real-world data sets only exist for recent, relatively short (<100 years) time spans. This limits our ability to study centennial/millennial... |  | Bioarchaeology, Environmental archaeology, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | 2023-12-12 14:37:22 | View | |

04 Oct 2023

IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A "para-description"Hagmann, Dominik; Reiner, Franziska https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5vwg8The IUENNA project: integrating old data and documentation for future archaeologyRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Nina Richards and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Nina Richards and 3 anonymous reviewers

This recommended paper on the IUENNA project (Hagmann and Reiner 2023) is not a paper in the traditional sense, but it is a reworked version of a project proposal. It is refreshing to read about a project that has just started and see what the aims of the project are. This ties in with several open science ideas and standards (e.g. Brinkman et al. 2023). I am looking forward to see in a few years how the authors managed to reach the aims and goals of the project. The IUENNA project deals with the legacy data and old excavations on the Hemmaberg and in the Jauntal. Archaeological research in this small, but important region, has taken place for more than a century, revealing material from over 2000 years of human history. The Hemmaberg is well known for its late antique and early medieval structures, such as roads, villas and the various churches. The wider Jauntal reveals archaeological finds and features dating from the Iron Age to the recent past. The authors of the paper show the need to make sure that the documentation and data of these past archaeological studies and projects will be accessible in the future, or in their own words: "Acute action is needed to systematically transition these datasets from physical filing cabinets to a sustainable, networked virtual environment for long-term use" (Hagmann and Reiner 2023: 5). The papers clearly shows how this initiative fits within larger developments in both Digital Archaeology and the Digital Humanities. In addition, the project is well grounded within Austrian archaeology. While the project ties in with various international standards and initiatives, such as Ariadne (https://ariadne-infrastructure.eu/) and FAIR-data standards (Wilkinson et al. 2016, 2019), it would benefit from the long experience institutes as the ADS (https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/) and DANS (see Data Station Archaeology: https://dans.knaw.nl/en/data-stations/archaeology/) have on the storage of archaeological data. I would also like to suggest to have a look at the Dutch SIKB0102 standard (https://www.sikb.nl/datastandaarden/richtlijnen/sikb0102) for the exchange of archaeological data. The documentation is all in Dutch, but we wrote an English paper a few years back that explains the various concepts (Boasson and Visser 2017). However, these are a minor details or improvements compared to what the authors show in their project proposal. The integration of many standards in the project and the use of open software in a well-defined process is recommendable. The IUENNA project is an ambitious project, which will hopefully lead to better insights, guidelines and workflows on dealing with legacy data or documentation. These lessons will hopefully benefit archaeology as a discipline. This is important, because various (European) countries are dealing with similar problem, since many excavations of the past have never been properly published, digitalized or deposited. In the Netherlands, for example, various projects dealt with publication of legacy excavations in the Odyssee-project (https://www.nwo.nl/onderzoeksprogrammas/odyssee). This has led to the publication of various books and datasets (24) (https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:34359), but there are still many datasets (8) missing from the various projects. In addition, each project followed their own standards in creating digital data, while IUENNA will make an effort to standardize this. There are still more than 1000 Dutch legacy excavations still waiting to be published and made into a modern dataset (Kleijne 2010) and this is probably the case in many other countries. I sincerely hope that a successful end of IUENNA will be an inspiration for other regions and countries for future safekeeping of legacy data. References Boasson, W and Visser, RM. 2017 SIKB0102: Synchronizing Excavation Data for Preservation and Re-Use. Studies in Digital Heritage 1(2): 206–224. https://doi.org/10.14434/sdh.v1i2.23262 Brinkman, L, Dijk, E, Jonge, H de, Loorbach, N and Rutten, D. 2023 Open Science: A Practical Guide for Early-Career Researchers https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7716153 Hagmann, D and Reiner, F. 2023 IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A ‘para-description’. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5vwg8 Kleijne, JP. 2010. Odysee in de breedte. Verslag van het NWO Odyssee programma, kortlopend onderzoek: ‘Odyssee, een oplossing in de breedte: de 1000 onuitgewerkte sites, die tot een substantiële kennisvermeerdering kunnen leiden, digitaal beschikbaar!’ ‐ ODYK‐09‐13. Den Haag: E‐depot Nederlandse Archeologie (EDNA). https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-z25-g4jw Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Aalbersberg, IjJ, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, ’t Hoen, PAC, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Velterop, J, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2016 The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1): 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Jan Aalbersberg, I, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, Hoen, PAC ’t, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Jan Velterop, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2019 Addendum: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 6(1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0009-6

| IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A "para-description" | Hagmann, Dominik; Reiner, Franziska | <p>The Go!Digital 3.0 project IUENNA – an acronym for “openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology” – embraces a comprehensive open science methodology. It focuses on the archaeological micro-region of the Jauntal Valley ... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Computational archaeology | Ronald Visser | 2023-04-06 13:36:16 | View | |

08 Feb 2024

CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient CoinsUlrike Peter, Claus Franke, Jan Köster, Karsten Tolle, Sebastian Gampe, Vladimir F. Stolba https://zenodo.org/records/8263517The valuable Corpus Nummorum: a not so Little MinionRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Fleur Kemmers and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Fleur Kemmers and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper under review/recommendation deals with Corpus Nummorum (Peter et al. 2024). The Corpus Nummorum (CN) is web portal for ancient Greek coins from various collections (https://www.corpus-nummorum.eu/). The CN is a database and research tool for Greek coins dating between 600 BCE to 300 CE. While many traditional collection databases aim at collecting coins, CN also includes coin dies, coin types and issues. It aims at achieving a complete online coin type catalogue. The paper is not a paper in a traditional sense, but presents the CN as a tool and shows the functionalities in the system. The relevance and the possibilities of the CN for numismatists is made clear in the paper and the merits are clear even for me as a Roman archaeologist and non-numismatist. The CN was presented as a poster at the CAA 2023 in Amsterdam during “S03. Our Little Minions pt. V: small tools with major impact”, organized by Moritz Mennenga, Florian Thiery, Brigit Danthine and myself (Mennenga et al. 2023). Little Minions help us significantly in our daily work as small self-made scripts, home-grown small applications and small hardware devices. They often reduce our workload or optimize our workflows, but are generally under-represented during conferences and not often presented to the outside world. Therefore, the Little Minions form a platform that enables researchers and software engineers to share these tools (Thiery, Visser and Mennenga 2021). Little Minions have become a well known happening within the CAA-community since we started this in 2018, also because we do not only allow 10-minute lightning talks, but also spontaneous stand-up presentations during the conference. A full list of all minions presented in the past, can be found online: https://caa-minions.github.io/minions/. In a strict sense the CN would not count as a Little Minion, because it is a large project consisting of many minions that help a numismatist in his/her daily work. The CN seems a very Big Minion in that sense. Personally, I am very happy to see the database being developed as a fully open system and that code can be found on Github (https://github.com/telota/corpus-nummorum-editor), and also made citable with citation information in GitHub (see https://citation-file-format.github.io/) and a version deposited in Zenodo with DOI (Köster and Franke 2024). In addition, the authors claim that the CN will be shared based on the FAIR-principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016, 2019). These guidelines are developed to improve the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse of digital data. I feel that CN will be a way forward in open numismatics and open archaeology. The CN is well known within the numismatist community and it was hard to find reviewers in this close community, because many potential reviewers work together with one or more of the authors, or are involved in the project. This also proves the relevance of the CN to the research community and beyond. Luckily, a Roman numismatist and a specialist in digital/computational archaeology were able to provide valuable feedback on the current paper. The reviewers only submitted feedback on the first version of the paper (Peter et al. 2023). The numismatist was positive on the content and the usefulness of CN for the discipline in general. However, she pointed out some important points that need to be addressed. The digital specialist was positive is various aspects, but also raised some important issues in relation to technical aspects and the explanation thereof. While both were positive on the project and the paper in general, both reviewers pointed out some issues that were largely addressed in the second version of this paper. The revised version was edited throughout and the paper was strongly improved. The Corpus Nummorum is well presented in this easy to read paper, although the explanations can sometimes be slightly technical. This paper gives a good introduction to the CN and I recommend this for publication. I sincerely hope that the CN will contribute and keep on contributing to the domains of numismatics, (digital) archaeology and open science in general. References Köster, J and Franke, C. 2024 Corpus Nummorum Editor. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10458195 Mennenga, M, Visser, RM, Thiery, F and Danthine, B. 2023 S03. Our Little Minions pt. V: small tools with major impact. In:. Book of Abstracts. CAA 2023: 50 Years of Synergy. Amsterdam: Zenodo. pp. 249–251. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7930991 Peter, U, Franke, C, Köster, J, Tolle, K, Gampe, S and Stolba, VF. 2023 CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.8263518 Peter, U., Franke, C., Köster, J., Tolle, K., Gampe, S. and Stolba, V. F. (2024). CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins, Zenodo, 8263517, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8263517 Thiery, F, Visser, RM and Mennenga, M. 2021 Little Minions in Archaeology An open space for RSE software and small scripts in digital archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.4575167 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Aalbersberg, IjJ, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, ’t Hoen, PAC, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Velterop, J, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2016 The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1): 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Jan Aalbersberg, I, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, Hoen, PAC ’t, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Jan Velterop, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2019 Addendum: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 6(1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0009-6 | CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins | Ulrike Peter, Claus Franke, Jan Köster, Karsten Tolle, Sebastian Gampe, Vladimir F. Stolba | <p>CORPUS NUMMORUM indexes ancient Greek coins from various landscapes and develops typologies. The coins and coin types are published on the multilingual website www.corpus-nummorum.eu utilizing numismatic authority data and adhering to FAIR prin... |  | Antiquity, Classic | Ronald Visser | 2023-08-18 17:37:51 | View | |

05 Jun 2023

SEAHORS: Spatial Exploration of ArcHaeological Objects in R ShinyROYER, Aurélien, DISCAMPS, Emmanuel, PLUTNIAK, Sébastien, THOMAS, Marc https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7957154Analyzing piece-plotted artifacts just got simpler: A good solution to the wrong problem?Recommended by Reuven Yeshurun based on reviews by Frédéric Santos, Jacqueline Meier and Maayan LevPaleolithic archaeologists habitually measure 3-coordinate data for artifacts in their excavations. This was first done manually, and in the last three decades it is usually performed by a total station and associated hardware. While the field recording procedure is quite straightforward, visualizing and analyzing the data are not, often requiring specialized proprietary software or coding expertise. Here, Royer and colleagues (2023) present the SEAHORS application, an elegant solution for the post-excavation analysis of artifact coordinate data that seems to be instantly useful for numerous archaeologists. SEAHORS allows one to import and organize field data (Cartesian coordinates and point description), which often comes in a variety of formats, and to create various density and distribution plots. It is specifically adapted to the needs of archaeologists, is free and accessible, and much simpler to use than many commercial programs. The authors further demonstrate the use of the application in the post-excavation analysis of the Cassenade Paleolithic site (see also Discamps et al., 2019). While in no way detracting from my appreciation of Royer et al.’s (2023) work, I would like to play the devil’s advocate by asking whether, in the majority of cases, field recording of artifacts in three coordinates is warranted. Royer et al. (2023) regard piece plotting as “…indispensable to propose reliable spatial planimetrical and stratigraphical interpretations” but this assertion does not hold in all (or most) cases, where careful stratigraphic excavation employing thin volumetric units would do just as well. Moreover, piece-plotting has some serious drawbacks. The recording often slows excavations considerably, beyond what is needed for carefully exposing and documenting the artifacts in their contexts, resulting in smaller horizontal and vertical exposures (e.g., Gilead, 2002). This typically hinders a fuller stratigraphic and contextual understanding of the excavated levels and features. Even worse, the method almost always creates a biased sample of “coordinated artifacts”, in which the most important items for understanding spatial patterns and site-formation processes – the small ones – are underrepresented. Some projects run the danger of treating the coordinated artifacts as bearing more significance than the sieve-recovered items, preferentially studying the former with no real justification. Finally, the coordinated items often go unassigned to a volumetric unit, effectively disconnecting them from other types of data found in the same depositional contexts. The advantages of piece-plotting may, in some cases, offset the disadvantages. But what I find missing in the general discourse (certainly not in the recommended preprint) is the “theory” behind the seemingly technical act of 3-coordinate recording (Yeshurun, 2022). Being in effect a form of sampling, this practice needs a rethink about where and how to be applied; what depositional contexts justify it, and what the goals are. These questions should determine if all “visible” artifacts are plotted, or just an explicitly defined sample of them (e.g., elongated items above a certain length threshold, which should be more reliable for fabric analysis), or whether the circumstances do not actually justify it. In the latter case, researchers sometimes opt for using “virtual coordinates” within in each spatial unit (typically 0.5x0.5 m), essentially replicating the data that is generated by “real” coordinates and integrating the sieve-recovered items as well. In either case, Royer et al.’s (2023) solution for plotting and visualizing labeled points within intra-site space would indeed be an important addition to the archaeologists’ tool kits.

References cited Discamps, E., Bachellerie, F., Baillet, M. and Sitzia, L. (2019). The use of spatial taphonomy for interpreting Pleistocene palimpsests: an interdisciplinary approach to the Châtelperronian and carnivore occupations at Cassenade (Dordogne, France). Paleoanthropology 2019, 362–388. https://doi.org/10.4207/PA.2019.ART136 Gilead, I. (2002). Too many notes? Virtual recording of artifacts provenance. In: Niccolucci, F. (Ed.). Virtual Archaeology: Proceedings of the VAST Euroconference, Arezzo 24–25 November 2000. BAR International Series 1075, Archaeopress, Oxford, pp. 41–44. Royer, A., Discamps, E., Plutniak, S. and Thomas, M. (2023). SEAHORS: Spatial Exploration of ArcHaeological Objects in R Shiny Zenodo, 7957154, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7929462 Yeshurun, R. (2022). Intra-site analysis of repeatedly occupied camps: Sacrificing “resolution” to get the story. In: Clark A.E., Gingerich J.A.M. (Eds.). Intrasite Spatial Analysis of Mobile and Semisedentary Peoples: Analytical Approaches to Reconstructing Occupation History. University of Utah Press, pp. 27–35.

| SEAHORS: Spatial Exploration of ArcHaeological Objects in R Shiny | ROYER, Aurélien, DISCAMPS, Emmanuel, PLUTNIAK, Sébastien, THOMAS, Marc | <p style="text-align: justify;">This paper presents SEAHORS, an R shiny application available as an R package, dedicated to the intra-site spatial analysis of piece-plotted archaeological remains. This open-source script generates 2D and 3D scatte... |  | Computational archaeology, Spatial analysis, Theoretical archaeology | Reuven Yeshurun | 2023-02-24 16:01:44 | View | |

02 Nov 2020

Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case StudyJoseph Lewis https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/mxas2A probabilistic method for Least Cost Path calculation.Recommended by Otis Crandell based on reviews by Georges Abou Diwan and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper entitled “Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study” [1] submitted by J. Lewis presents an innovative approach to applying Least Cost Path (LCP) analysis to incorporate uncertainty of the Digital Elevation Model used as the topographic surface on which the path is calculated. The proposition of using Monte Carlo simulations to produce numerous LCP, each with a slightly different DEM included in the error range of the model, allows one to strengthen the method by proposing a probabilistic LCP rather than a single and arbitrary one which does not take into account the uncertainty of the topographic reconstruction. This new method is integrated in the R package leastcostpath [2]. The author tests the method using a Roman road built along a ridge in Cumbria, England. The integration of the uncertainty of the DEM, thanks to Monte Carlo simulations, shows that two paths could have the same probability to be the real LCP. One of them is indeed the path that the Roman road took. In particular, it is one of two possibilities of LCP in the south to north direction. This new probabilistic method therefore strengthens the reconstruction of past pathways, while also allowing new hypotheses to be tested, and, in this case study, to suggest that the northern part of the Roman road’s location was selected to help the northward movements. [1] Lewis, J., 2020. Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study. SocArXiv, mxas2, ver 17 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology, 10.31235/osf.io/mxas2. [2] Lewis, J., 2020. leastcostpath: Modelling Pathways and Movement Potential Within a Landscape. R package. Version 1.7.4. | Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study | Joseph Lewis | <p>The movement of past peoples in the landscape has been studied extensively through the use of Least Cost Path (LCP) analysis. Although methodological issues of applying LCP analysis in Archaeology have frequently been discussed, the effect of v... |  | Spatial analysis | Otis Crandell | Adam Green, Georges Abou Diwan | 2020-08-05 12:10:46 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer