Gamification of an archaeological park: The Living Hill Project as work-in-progress

Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project

Abstract

Recommendation: posted 11 October 2023, validated 11 October 2023

Hageneuer, S. (2023) Gamification of an archaeological park: The Living Hill Project as work-in-progress. Peer Community in Archaeology, 100399. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.archaeo.100399

Recommendation

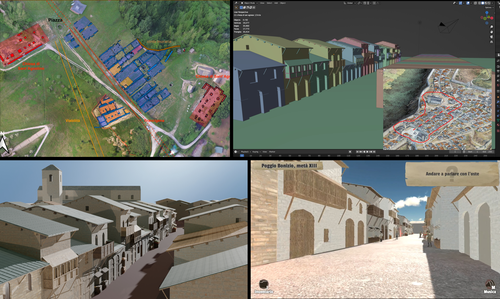

This paper (2023) describes The Living Hill project dedicated to the archaeological park and fortress of Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi, Italy. The project is a collaboration between the Poggibonsi excavation and Entertainment Games App, Ltd. From the start, the project focused on the question of the intended audience rather than on the used technology. It was therefore planned to involve the audience in the creation of the game itself, which was not possible after all due to the covid pandemic. Nevertheless, the game aimed towards a visit experience as close as possible to reality to offer an educational tool through the video game, as it offers more periods than the medieval period showcased in the archaeological park itself.

The game mechanics differ from a walking simulator, or a virtual tour and the player is tasked with returning three lost objects in the virtual game. While the medieval level was based on a 3D scan of the archaeological park, the other two levels were reconstructed based on archaeological material. Currently, only a PC version is working, but the team works on a mobile version as well and teased the possibility that the source code will be made available open source. Lastly, the team also evaluated the game and its perception through surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Although the surveys were only based on 21 persons, the results came back positive overall.

The paper is well-written and follows a consistent structure. The authors clearly define the goals and setting of the project and how they developed and evaluated the game. Although it has be criticized that the game is not playable yet and the size of the questionnaire is too low, the authors clearly replied to the reviews and clarified the situation on both matters. They also attended to nearly all of the reviewers demands and answered them concisely in their response. In my personal opinion, I can fully recommend this paper for publication.

For future works, it is recommended that the authors enlarge their audience for the quesstionaire in order to get more representative results. It it also recommended to make the game available as soon as possible also outside of the archaeological park. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their concise and constructive criticism to this paper as well as for their time.

References

Mariotti, Samanta. (2023) Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project, Zenodo, 8302563, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563

The recommender in charge of the evaluation of the article and the reviewers declared that they have no conflict of interest (as defined in the code of conduct of PCI) with the authors or with the content of the article. The authors declared that they comply with the PCI rule of having no financial conflicts of interest in relation to the content of the article.

The research program of C.AP.I. was funded by the Tuscany Region, the University of Siena, the Foundation of the bank Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Archeòtipo Ltd. (the private company that manages the archaeological area on the hill of Poggibonsi and the open-air museum), and Entertainment Game Apps, Ltd. (a private company specialised in the development of historical serious games). This research was carried out as part of the PhD research project of the author, funded by a scholarship of the University of Bari “Aldo Moro”.

Evaluation round #1

DOI or URL of the preprint: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563

Version of the preprint: 1

Author's Reply, 04 Oct 2023

Decision by Sebastian Hageneuer , posted 24 Sep 2023, validated 24 Sep 2023

, posted 24 Sep 2023, validated 24 Sep 2023

I agree with the reviewers, that this article is a well-written and interesting paper. Nevertheless, the reviewers offer some advice on how to improve this important work and I urge the authors to take this constructive criticism to improve their paper in the mentioned points. I also ask the authors to create a document with a list of changes made relating to the points the reviewers made and upload this within PCI Archaeology when the new revised version is ready.

Reviewed by Andrew Reinhard, 19 Sep 2023

Review by Andrew Reinhard of “Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project,” by Samanta Mariotti, University of Bari “Aldo Moro.”

This article describes the planning, execution, and outcome of a digital public outreach project to communicate the archaeology of a medieval village, Poggio Bonizio, as a series of three interactive digital narratives in the form of a video game. Author Samanta Mariotti's article joins a handful of other practical, reflexive reports on the outcomes of digital heritage projects, and presents a model for future white papers to follow.

Samanta Mariotti is one of the bright emerging voices in archaeogaming, and her article developed for PCI Archaeology is an excellent example of what cultural heritage professionals can look forward to as archaeologists continue to experiment with interactive digital spaces to communicate their evidence-based findings to a wider public. The article is clearly written and organized, presents meaningful research questions and well-considered design for how to answer them, and provides essential analysis and conclusions to a project that is still ongoing with realistic plans for future development and deployment. I have no concerns regarding her team’s ethics, and felt that her conclusions presented an honest assessment of the outcomes so far.

The title, abstract, and introduction clearly reflect the content and conclusions of the article. The introduction places the case study within the wider intersection of archaeology and video games with special attention paid to past publications about pedagogy and also historical and archaeological reconstruction through digital means. Driving the article are the dual questions of how best to present the Archaeological Park and Fortress of Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi, Italy, and to what audiences. Mariotti then describes in detail how the team chose to answer these questions, offering an in-depth look into methodology and the game’s development cycle and alpha testing. Her presentation of the team’s workflow, which includes problems and workarounds, makes the article required reading for other archaeological projects wishing to undertake a similar approach to presenting their heritage and archaeology to the public. It is of crucial importance that any heritage project publish at the very minimum a white paper on their methods and outcomes, which will help guide future development.

The discussion of the methods and early reception by the public of an alpha version of The Living Hill is detailed enough, but I had a few questions which I hope the author will consider as part of a modest revision. These questions follow the main text of this review.

The references for the article were largely complete and current. Mariotti is wise to cite earlier works by Erik Champion and Tara Copplestone and others. The article might benefit additionally from bibliography centered around case studies published by museums about their approaches to interactive digital “edutainment”, how these succeeded and failed, and how Mariotti’s approach to communicating archaeology-driven narratives is both similar to and different from those of her museum-based colleagues. The tables and figures were clearly presented, objective, and were of the right amount for the scope of the article. The inclusion of the audience questionnaire was helpful. As soon as I read the article, I found myself wanting to play a demo version of the game, and I am hopeful that the author will include a link to it in the article’s published version or record.

I do have a few lingering questions and comments that the author should consider working into the substance of an already excellent article:

1. I would recommend adding “archaeogaming” as a keyword to improve the article’s discoverability.

2. In the introduction, the author [correctly] states: “The integration of video games with archaeology in Italy has been challenging due to academics viewing commercial products as inferior knowledge, the misconception that video games are childish entertainment, and the lack of understanding of the interactive industry by archaeologists.” While I agree, I do think a citation is needed here.

3. Further in the introduction, the author writes: “As a result, the domain of cultural and archaeological heritage in Italy has recently seen an upsurge of interest in video games. This is largely due to the attention from museums and academics as well as the incentives provided for digital innovation by local administrations and the government." I am also wondering if this uptick in interest also be driven by recent appearances of Roman and Italic games and characters including Assassin’s Creed Origins, The Forgotten City, Imperator: Rome, Asterix & Obelix and others?

4. In the Methods/Objectives section, “HGR Framework” should be defined (or at least footnoted) immediately after its first mention.

5. In the Methods/Objectives section, what percentage of various demographics identified as being “digital”, or what was the shared comfort level of using digital things, and of that group, what subset had any familiarity with any kind of digital game, mobile or otherwise? The author does state some numbers later in the article, but a general statement could be made earlier here with a hint at the actual numbers to be presented below.

6. The author may wish to further define the term “video game” by some rubric (perhaps Ian Bogost’s?) to disambiguate it from “immersive narrative experience” or “interactive story” or similar. There is a goal present, to find and return three objects by way of interacting with the environment and non-player characters (NPCs), as opposed to The Living Hill being a walking simulator in which people can tour the site digitally without any goal. The game allows the archaeological team to focus the attention of the audience on things deemed important to the site.

7. Also in the Methods/Objectives section, would it be possible to describe a little more the technological landscape for the average community school: Internet access and reliability of a connection, access to hardware, home computer use, etc.? In 2023 in Italy, is there technological equity for students of history in lower and upper grades?

8. Mariotti is absolutely correct when she writes: “Further research is necessary to investigate in greater detail the actual effectiveness of the various types of video games, to define a methodology based on metrics and evaluation tools, even more so those with cultural/archaeological content. Games applied to cultural heritage have proven to potentially be an independent instrument, capable of bringing information, lasting engagement, knowledge, and curiosity to a very diversified public. So, how do we assess these further aspects?” In light of the absence of many case studies about elearning effectiveness merging history with games, preliminary queries could go directly to online discussions on reddit and elsewhere regarding the historicity and accuracy of ancient cultures and monuments in games, at least to get a ground-level idea of the public perception of antiquity through games.

9. I was curious to learn what the average time of engagement was for various testing groups who played an early version of the game. Some people wanted to continue playing, but was there an average play-time before users wanted to do something else (or had to be someplace else)? Will the finished game be available to play within the archaeological park through a dedicated computer station?

10. In the Conclusions, I was wondering what the plan is for sustainability and preservation or for updating the code/assets of The Living Hill. Would it be possible to release the assets and game code as open source once the finished game has launched to allow the community to create their own stories within the landscape and architecture created by the team? This might be beneficial for continued public outreach and for community engagement especially by the people who live in the area of the archaeological park. Those modded stories could then be shared online through the park’s website, or pushed as free downloadable content (DLC) to people who downloaded and installed the game.

11. Mariotti writes at the very end: “A thorough analysis of these factors may lead to alternative choices for game type, narrative, and visuals or even lead to entirely different kinds of tools for communicating our research, even if creating a video game for cultural heritage is currently popular.” I would recommend adding a citation regarding the popularity of creating games for cultural heritage engagement and education. Who else is doing this now, and where can we interact with examples?

Submitted by Andrew Reinhard, Research Affiliate, Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW), New York University, ar6507@nyu.edu.

https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.archaeo.100399.rev11Reviewed by anonymous reviewer 1, 15 Sep 2023

Dr. Mariotti’s paper, “Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project,” presents a new digital project that conveys the archaeological site of Poggio Imperiale in the form of a newly designed video game.

There are several important strengths that that should be noted:

• Interdisciplinary Collaboration - Rather than an atempt by archaeologists to develop a video game, or an atempt by a video game company to portray archaeology, this project offers valuable insights because it highlights true collaboration between academic archaeologists, cultural heritage professionals, and individuals in the video game industry.

• Archaeologically-precise Reconstructions – The virtual environment provided in the game is, more than most archaeologically-based video games, developed from photogrammetric models of actual archaeological remains. These are much closer to archaeological recreations than artists’ interpretations, and that is commendable.

• Detailed Description & Data – I appreciate the level of detail the author provides for how the game was created, which has the potential to be useful for others wanting to atempt something similar. At the same time, the author also provides data-based feedback from users, which provides useful information for how the game was received.

Despite these merits, there are several things that Dr. Mariotti may want to address prior to final publication:

• English Usage – Overall the paper is clear and comprehensible; however, there are several small errors that could be addressed (e.g., “last decades” in line 17, “viewing commercial products as inferior knowledge” in lines 27-28). These aren’t grammatically wrong, but they sound a litle awkward in English (I think I’d go with something like “In recent decades…” or “viewing commercial products as providing unreliable information…”). Again, this doesn’t hinder overall understanding, but it is worth getting a native English speaker to check the article for instances like this.

• Highlight Your Question – The Introduction offers a compelling overview of the site and the digital project, but it’s not quite clear what question the author is going to answer in the remainder of the article. Is this about how to build video games based on archaeological excavations? Is it about understanding feedback from users of the video game? Is it a preliminary analysis that uses data from the open-air museum to provide guidelines for a video game? There are lots of interesting directions it could go, but by the end of the intro, it would be useful to have the main question presented clearly to the reader.

• Literature Review (Contextualize within Similar Games) – The author notes that “several video games dedicated to archaeological and cultural content have been developed in Italy recently” in lines 205-206. It would be great to hear a litle bit about these and know how this game builds off those predecessors and how (and why) it moves in new directions as well.

• Discussion – How do the results from your survey compare to feedback that other games have received? Did the preliminary results of the survey for this game provide similar trends to other similar games? Or did it diverge from feedback gathered from other similar games?

• Future Directions – In the conclusion, it would be useful to add a couple sentences about the next steps for The Living Hill project. Now that you have round 1 of feedback, where do you go from here?

Overall, this article provides a valuable contribution to the disciplines of archaeology, cultural heritage, and education. It’s particularly good at describing the development process and the game itself. The detail included regarding the development of the game and the preliminary results of the survey are both highly useful for scholars interested in conveying complex archaeological information to a broad and varied popular audience. The article, however, could use a litle work on framing, especially with how the game and survey results compare to similar atempts to portray archaeology/archaeological sites through video games. As a result, I recommend that the author revise the article to further build this framework, and then resubmit the article for publication.

Download the review https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.archaeo.100399.rev12

Reviewed by Erik Champion, 23 Sep 2023

This is, in general, a well-written and clear case study on archaeogaming and related issues-paper. I am not sure what the game mechanics or goal is in the game or the options available.

The questionnaire, is the Likert Scale insightful ? 1-5, " From 1 to 5, how much did you like The Living Hill?" What is a 5? How would nongamers consider a 5?

The sentence starting 194 is a little hard to understand, I suggest, rewriting for clarity: "The game is currently only accessible through the PC platform, while the mobile version of the game still requires some work to fix technical issues and some bugs regarding the mechanics and mainly to find a solution to make it available in the app stores since the file size is quite large for a standard mobile application (around 1.5 GB). "

The information on Italian-related games was interesting and I would have appreciated reading more on that. More on how archaeologists/heritage experts and the general public may diverge on expectations and judgments and general understanding derived from the game could be useful. I am not sure that an emphasis on gender and age is so useful when derived from a small sample size.

https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.archaeo.100399.rev13