Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 Oct 2023

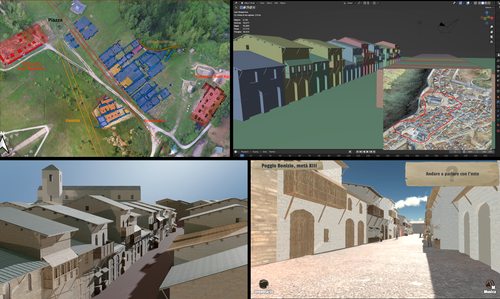

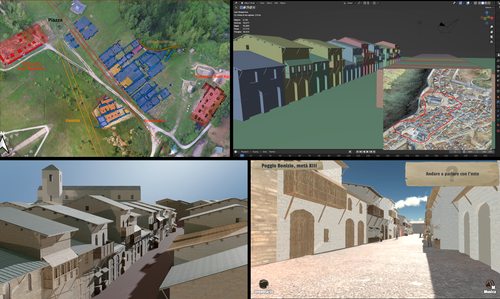

Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill ProjectSamanta Mariotti https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563Gamification of an archaeological park: The Living Hill Project as work-in-progressRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (2023) describes The Living Hill project dedicated to the archaeological park and fortress of Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi, Italy. The project is a collaboration between the Poggibonsi excavation and Entertainment Games App, Ltd. From the start, the project focused on the question of the intended audience rather than on the used technology. It was therefore planned to involve the audience in the creation of the game itself, which was not possible after all due to the covid pandemic. Nevertheless, the game aimed towards a visit experience as close as possible to reality to offer an educational tool through the video game, as it offers more periods than the medieval period showcased in the archaeological park itself. The game mechanics differ from a walking simulator, or a virtual tour and the player is tasked with returning three lost objects in the virtual game. While the medieval level was based on a 3D scan of the archaeological park, the other two levels were reconstructed based on archaeological material. Currently, only a PC version is working, but the team works on a mobile version as well and teased the possibility that the source code will be made available open source. Lastly, the team also evaluated the game and its perception through surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Although the surveys were only based on 21 persons, the results came back positive overall. The paper is well-written and follows a consistent structure. The authors clearly define the goals and setting of the project and how they developed and evaluated the game. Although it has be criticized that the game is not playable yet and the size of the questionnaire is too low, the authors clearly replied to the reviews and clarified the situation on both matters. They also attended to nearly all of the reviewers demands and answered them concisely in their response. In my personal opinion, I can fully recommend this paper for publication. For future works, it is recommended that the authors enlarge their audience for the quesstionaire in order to get more representative results. It it also recommended to make the game available as soon as possible also outside of the archaeological park. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their concise and constructive criticism to this paper as well as for their time. References Mariotti, Samanta. (2023) Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project, Zenodo, 8302563, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563 | Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of *The Living Hill* Project | Samanta Mariotti | <p>Video games are now recognised as a valuable tool for disseminating and enhancing archaeological heritage. In Italy, the recent institutionalisation of Public Archaeology programs and incentives for digital innovation has resulted in a prolifer... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Europe, Medieval, Post-medieval | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-30 20:25:32 | View | |

01 Dec 2021

A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-MaatheideSonja Tomasso, Dries Cnuts, Justin Coppe, Marijn Van Gils, Ferdi Geerts, Marc De Bie, Veerle Rots https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pf3smPotential of a large-scale functional analysis to reconstructing past human activities at the Final Palaeolithic site of Lommel-MaatheideRecommended by Marta Arzarello and Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti and Ana Abrunhosa and Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti and Ana Abrunhosa

The paper “A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide” [1] focuses on the final Palaeolithic (Federmesser) site of Lommel-Maatheide. Federmesser sites from northern Belgium such as Lommel-Maatheide, Meer and Rekem, show evidence for dense human occupation of specific areas located on top of Tardiglacial dunes nearby water bodies [2]. Preserved spatial distribution of finds at the sites suggest different activity areas and the presence of habitat structures [2]. However, because of the low organic preservation at the sites, functional analyses of lithic assemblages have the potential to significantly contribute to the spatial organisation of activities at these sites. This study by Tomasso et al. [1], represents an excellent example of a large-scale integrated approach to the study of lithic industries. The article undoubtedly demonstrates the potential of the proposed methodology and the reliability of the results obtained. The article explores two different aspects (linked and excellently interconnected here): the possibility to apply use wear, residue and fracture analyses, on lithic assemblages affected by taphonomical alterations and to study lithic assemblages from dune landscapes. The study allows to answer differentiated questions: what is the influence of taphonomical alterations on use wear analysis? How do excavation methods impact the formation of use wear and the preservation of residues? Can we recognize distinct domestic activities? The article also provides an interesting hypothesis about hunting activities and propulsion methods. The applied methodology is effectively interdisciplinary and innovative. It demonstrates how a truly integrated and articulated approach can represent the turning point for going beyond a mainly descriptive dimension to move towards a real understanding of the sites. Studies dedicated to the analysis of the propulsion mode are not very frequent, but they are surely very important to better understand human behaviour [3]. Here, the methodology developed for the evaluation of the propulsion mode represent an important starting point for the definition of a new approach. Morphological and morphometrical analysis are integrated to the evaluation of the mechanical stress, to fracture delineations and to the hafting system (the latter defined on experimental basis). This article therefore underlines the potential of combining different approaches to functional analysis associated with a ‘tailored’ reference collection and applying them to a high number of artefacts for reconstructing past human activities involving materials that are otherwise not preserved in these contexts. [1] Tomasso, S., Cnuts, D., Coppe, J., Geerts, F., Gils, M.V., Bie, M.D., Rots, V. (2021). A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pf3sm, ver 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. [2] De Bie, M., Van Gils, M. (2006). Les habitats des groupes à Federmesser (aziliens) dans le Nord de la Belgique. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 103, 781–790. [3] Coppe, J., Lepers, C., Clarenne, V., Delaunois, E., Pirlot, M. and Rots V. (2019). Ballistic Study Tackles Kinetic Energy Values of Palaeolithic Weaponry. Archaeometry, (61)4, 933-956. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12452 | A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide | Sonja Tomasso, Dries Cnuts, Justin Coppe, Marijn Van Gils, Ferdi Geerts, Marc De Bie, Veerle Rots | <p>The vast Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide, which is located in the Campine region (Northern Belgium), revealed the presence of numerous Final Palaeolithic concentrations situated on a large Late Glacial sand ridge on the northern edg... | Environmental archaeology, Landscape archaeology, Lithic technology, Traceology, Upper Palaeolithic | Marta Arzarello | 2021-09-14 17:04:38 | View | ||

20 Jun 2020

Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32-28 ka cal. BP) in France.Anaïs Vignoles, William E. Banks, Laurent Klaric, Masa Kageyama, Marlon E. Cobos, Daniel Romero-Alvarez https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/ud3hjUnderstanding Palaeolithic adaptations through niche modelling - the case of the French Middle GravettianRecommended by Felix Riede based on reviews by Andreas Maier and João MarreirosThe paper entitled “Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32-28 ky cal. BP) in France” [1] submitted by A. Vignoles and colleagues offers a robust and interesting new analysis of the niche differences between the Rayssian and Noaillian facies of the Middle Gravettian in France. Understanding technological variability in the Palaeolithic is a long-standing challenge. Previous debates have vacillated between strong, quasi-ethnic culture-historical interpretations rooted in the traditional European school and extreme functional stances that would see artefact forms and their frequencies with assemblages conditioned by site function. While both positions have their merits, many empirical and conceptual caveats haunt them equally [see 2]. In this new study Vignoles and colleagues, so-called eco-cultural niche modelling is applied in an attempt to explore whether, and if so, which environmental background factors may have conditioned the emergence and persistence of two sub-cultural categories (facies) within the Middle Gravettian: the Rayssian and the Noaillian. These are are defined through, respectively, a specific knapping method and the presence of a specific burin type, and the occurrence of these seems divided by the Garonne River. Eco-cultural niche modelling has emerged as an archaeological application of distribution models widely employed in ecology, including palaeoecology, to understand organismal niche envelopes [3]. They constitute powerful tools for using the spatial and chronological information inherent in the archaeological record to up-scale interpretations of human-environment relations beyond individual site stratigraphies or dating series. Another important feature of such models is that their performance can, as Vignoles et al. also show, be formally evaluated and replicated. Following on from earlier applications of such techniques [e.g. 4], the authors here present an interesting study that uses very specific archaeological indicators – namely the Raysse method and the Noaillian burin – as defining features for the units (communities, traditions) whose adaptations they investigate. While broad tool types have previously been used as cultural taxonomic indicators in niche modelling studies [5], the present study is ambitious in its attempt to understand variability at a relatively small spatial scale. This mirrors equally interesting attempts of doing so in later prehistoric contexts [6]. Applications of niche modelling that use analytical units defined through archaeological characteristics (technology, typology) are opening up exciting new opportunities for pinning down precisely which environmental or climatic features these cultural components reference, if any. The study by Vignoles et al. makes a good case. At the same time, this approach also acutely raises questions of cultural taxonomy, of how we define our units of analysis and what they might mean [7]. It remains unclear to whether we can define such units on the basis of very different technological traits if the aim is to then use them as taxonomically equivalent in subsequent analyses. There is also a risk that these facies become reified as traditions of sub-cultures – then often further equated with specific people – through an overly normative view of their constituent technological elements. In addition, studies of adaptation in principle need to be conscious of the so-called ‘Galton’s Problem’, where the historical relatedness of the analytical units in question need to be taken into account in seeking salient correlations between cultural and environmental features [8]. In pushing forward eco-cultural niche modelling, the study by Vignoles et al. thus takes us some way forward in understanding the potentially adaptive variability within the Gravettian; future work should consider more strongly the specific historical relatedness amongst the cultural taxa under study and follow more theory-driven definition thereof. Such definition would also allow the post-analysis interpretations of eco-cultural niche modelling to be more explicit. Without doubt, the Gravettian as a whole – including, for instance, phenomena such as the Maisierian [9] – would benefit from additional and extended applications of this method. Similarly, other periods of the Palaeolithic also characterized by such variability (e.g. the Magdalenian and Final Palaeolithic) offer additional cases moving forward. Bibliography [1] Vignoles, A. et al. (2020). Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in 1 the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32-28 ky cal. BP) in France. PCI Archaeology. 10.31219/osf.io/ud3hj [2] Dibble, H.L., Holdaway, S.J., Lin, S.C., Braun, D.R., Douglass, M.J., Iovita, R., McPherron, S.P., Olszewski, D.I., Sandgathe, D., 2017. Major Fallacies Surrounding Stone Artifacts and Assemblages. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24, 813–851. 10.1007/s10816-016-9297-8 [3] Svenning, J.-C., Fløjgaard, C., Marske, K.A., Nógues-Bravo, D., Normand, S., 2011. Applications of species distribution modeling to paleobiology. Quaternary Science Reviews 30, 2930–2947. 10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.06.012 [4] Banks, W.E., d’Errico, F., Dibble, H.L., Krishtalka, L., West, D., Olszewski, D.I., Townsend Petersen, A., Anderson, D.G., Gillam, J.C., Montet-White, A., Crucifix, M., Marean, C.W., Sánchez-Goñi, M.F., Wolfarth, B., Vanhaeren, M., 2006. Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling: New Tools for Reconstructing the Geography and Ecology of Past Human Populations. PaleoAnthropology 2006, 68–83. [5] Banks, W.E., Zilhão, J., d’Errico, F., Kageyama, M., Sima, A., Ronchitelli, A., 2009. Investigating links between ecology and bifacial tool types in Western Europe during the Last Glacial Maximum. Journal of Archaeological Science 36, 2853–2867. 10.1016/j.jas.2009.09.014 [6] Whitford, B.R., 2019. Characterizing the cultural evolutionary process from eco-cultural niche models: niche construction during the Neolithic of the Struma River Valley (c. 6200–4900 BC). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11, 2181–2200. 10.1007/s12520-018-0667-x [7] Reynolds, N., Riede, F., 2019. House of cards: cultural taxonomy and the study of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Antiquity 93, 1350–1358. 10.15184/aqy.2019.49 [8] Mace, R., Pagel, M.D., 1994. The Comparative Method in Anthropology. Current Anthropology 35, 549–564. 10.1086/204317 [9] Pesesse, D., 2017. Is it still appropriate to talk about the Gravettian? Data from lithic industries in Western Europe. Quartär 64, 107–128. 10.7485/QU64_5 | Investigating relationships between technological variability and ecology in the Middle Gravettian (ca. 32-28 ka cal. BP) in France. | Anaïs Vignoles, William E. Banks, Laurent Klaric, Masa Kageyama, Marlon E. Cobos, Daniel Romero-Alvarez | <p>The French Middle Gravettian represents an interesting case study for attempting to identify mechanisms behind the typo-technological variability observed in the archaeological record. Associated with the relatively cold and dry environments of... |  | Europe, Lithic technology, Paleoenvironment, Peopling, Upper Palaeolithic | Felix Riede | 2020-03-23 12:16:20 | View | |

02 Sep 2023

Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation ToolsNikolai Paukkonen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7954534The Potential of Mobile 3D Documentation using Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 ProRecommended by Ying Tung Fung based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and 1 anonymous reviewerI am pleased to recommend the paper titled "Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools" for consideration and publication as a preprint (Paukkonen, 2023). The paper addresses a timely and relevant topic within the field of archaeology and offers valuable insights into the evolving landscape of 3D documentation methods. The advances in technology over the past decade have brought about significant changes in archaeological documentation practices. This paper makes a valuable contribution by discussing the emergence of affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation. Given the constraints that many archaeologists face with limited resources and tight timeframes, the comparison between photogrammetry based on a video captured by a DJI Osmo Pocket gimbal camera and iPhone 12 Pro LiDAR scans is of great significance. The research presented in the paper showcases a practical application of these new technologies in the context of a Finnish Early Modern period archaeological project. By comparing the acquisition processes and evaluating the accuracy, precision, ease of use, and time constraints associated with each method, the authors provide a comprehensive assessment of their potential for archaeological fieldwork. This practical approach is a commendable aspect of the paper, as it not only explores the technical aspects but also considers the practical implications for archaeologists on the ground. Furthermore, the paper appropriately addresses the limitations of these technologies, specifically highlighting their potential inadequacy for projects requiring a higher level of precision, such as Neolithic period excavations. This nuanced perspective adds depth to the discussion and provides a realistic portrayal of the strengths and limitations of the new documentation methods. In conclusion, the paper offers valuable insights into the future of 3D field documentation for archaeologists. The authors' thorough evaluation and practical approach make this study a valuable resource for researchers, practitioners, and professionals in the field. I believe that this paper would be an excellent addition to PCIArchaeology and would contribute significantly to the ongoing dialogue within the archaeological community. References Paukkonen, N. (2023) Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools, Zenodo, 8281263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8281263 | Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools | Nikolai Paukkonen | <p>New affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation has appeared during the last years. Both photogrammetry and laser scanning are becoming affordable for archaeologists, who often work with limited resources and tight time constra... |  | Europe, Post-medieval, Remote sensing | Ying Tung Fung | 2023-05-21 21:32:33 | View | |

26 Sep 2022

The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspectiveSolange Rigaud, John O’Hara, Laurent Charles, Elena Man-Estier, Patrick Paillet https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/z7pqgCaching up with the study of the procurement of symbolic raw materials in the Upper PalaeolithicRecommended by Beatrice Demarchi based on reviews by Begoña Soler Mayor , Catherine Dupont and Lawrence StrausThe manuscript "The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective" by Solange Rigaud and colleagues (Rigaud et al. 2022) is a perfect demonstration that appropriate scientific methodologies can be used effectively in order to enhance the historical value of findings from “old” collections, despite the lack of secure stratigraphic and contextual data. The shell assemblage (n = 377) investigated here (from Rochereil, Dordogne) had been excavated during the first half of the 20th century (Jude 1960) and reported in 1993 (Taborin 1993), but only this recent analysis revealed that it was composed of largely unmodified mollusc shells, most of allochthonous origin. Rigaud et al. interpret this finding as the raw materials used to produce personal ornaments. This is especially significant, because the focus of research has been on the manufacture, use and exchange of personal ornaments in prehistory, much less so on the procurement of the raw materials. As such, the manuscript adds substantially to the growing literature on Magdalenian social networks. The authors carried out detailed taxonomic analysis based on morphological and morphometric characteristics and identified at least nine different species, including Dentalium sp., Ocenebra erinaceus, Tritia reticulata and T. gibbosula, as well as some bivalve specimens (Mytilus, Glycymeris, Spondylus, Pecten). Most of the species are commonly found in personal ornament assemblages from the Magdalenian, reflecting intentional selection (also shown by the size sorting of some of the taxa), and cultural continuity. However, microscopic examinations revealed securely-identified anthropogenic modifications on a very limited number of specimens: one Glycymeris valve (used as an ochre container), one Cardiidae valve (presence of a groove), one perforated Tritia gibbosula and two perforated Tritia reticulata bearing striations. The authors interpret this combination of anthropogenic vs natural “signals” as signifying that the assemblage represents raw material selected and stored for further processing. Assessing the provenance and age of the shells is therefore paramount: the shells found at Rochereil belong to species that can be found on both the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. Assuming that molluscan taxa distribution in the past is comparable to that for the present day, this implies the exploitation of two catchment areas and long-distance transportation to the site: taking sea-level changes into account, during the Magdalenian the Mediterranean used to lie at a distance of 350 km from Rochereil, and the Atlantic was not significantly closer (~200 km). Importantly, exploitation of fossil shells cannot be discounted on the basis of the data presented here; direct dating of some of the specimens (e.g. by radiocarbon, or amino acid racemisation geochronology) would be beneficial to clarify this issue and in general to improve chronological control on the accumulation of shells. Nonetheless, the authors argue that the closest fossil deposits also lie more than 200 km away from the site, thus the material is allochthonous in origin. In synthesis, the Rochereil assemblage represents an important step towards a better understanding of the procurement chain and of the production of ornaments during the European Upper Palaeolithic. References Jude, P. E. (1960). La grotte de Rocherreil: station magdalénienne et azilienne, Masson. Rigaud, S., O'Hara, J., Charles, L., Man-Estier, E. and Paillet, P. (2022) The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective. SocArXiv, z7pqg, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/z7pqg Taborin, Y. (1993). La parure en coquillage au Paléolithique, CNRS éditions. | The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective | Solange Rigaud, John O’Hara, Laurent Charles, Elena Man-Estier, Patrick Paillet | <p>Personal ornaments manufactured on marine and fossil shell are a significant element of Upper Palaeolithic symbolic material culture, and are often found at considerable distances from Pleistocene coastlines or relevant fossil deposits. Here, w... |  | Europe, Symbolic behaviours, Upper Palaeolithic | Beatrice Demarchi | 2022-04-23 19:20:02 | View | |

14 Nov 2022

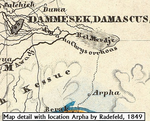

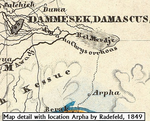

Raphana of the Decapolis and its successor Arpha - The search for an eminent Greco-Roman CityJens Kleb https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20550021Cross-comparison of classical sources, explorer and scientific reports and maps in the search of an ancient city: The example of Raphana of the DecapolisRecommended by Luc Doyon based on reviews by Rocco Palermo and Francesca Mazzilli based on reviews by Rocco Palermo and Francesca Mazzilli

Establishing the precise location of ancient cities constitutes a challenging task that requires the implementation of multi-disciplinary approaches. In his manuscript entitled “Raphana of the Decapolis and its successor Arpha: The search of an eminent Greco-Roman city”, Kleb (2022) proposes a convincing argument building on in-depth research of classical literary sources, literature review of explorer accounts and scientific publications from the 19th and 20th century as well as analysis of old and new maps, aerial photographs, and satellite images. This research report clearly emphasizes the importance of undertaking systematic interdisciplinary work on the topic to mitigate the uncertainties associated with the identification of Raphana, the Decapolis city first mentioned by Pliny the Elder. The Decapolis refers to a group of ten cities of Hellenistic traditions located on the eastern borders of the Roman Empire. This group of cities plays an important role in research that aims to contextualize the Judaean and Galilean history and to investigate urban centers in which different local and Greco-Roman influences met (Lichtenberger, 2021). While the location of most of the Decapolis cities is known and is (or was) subjected to systematic archaeological investigations (e.g., Eisenberg and Kowalewska, 2022; Makhadmeh et al., 2020; Shiyab et al., 2019), the location of others remain speculative. This is the case of Raphana for which the precise location remains difficult to establish owing in part to numerous name changes, limited information on the city structure, architecture, and size, etc. The research presented by Kleb (2022) has some merits, which is emphasized here, although the report is presented in an unusual format compared to traditional scientific articles, i.e., introduction, research background, methodology, results, and discussion. First, the extensive review of classical works allows the reader to gain a historical perspective on the change of names from Raepta/Raphana to Arpha/Arefa. The author argues these different names likely refer to a single location. Second, the author combs through an impressive literature from the 19th and 20th century and emphasize how some assumptions by explorers who visited the region were introduced in the scientific literature and remained unchallenged. Finally, the author gathers a remarkable quantity of old and new maps of the Golan, el-Ledja and Hauran regions and compare them with multiple lines of evidence to hypothesize that the location of Raphana may lie near Ar-Rafi’ah, also known as Bir Qassab, in the Ard el Fanah plain, a conclusion that now requires to be tested through fieldwork investigations. References Kleb, J. (2022) Raphana of the Decapolis and its successor Arpha - The search for an eminent Greco-Roman City. Figshare, 20550021, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20550021 Eisenberg, M. and Kowalewska, A. (2022). Funerary podia of Hippos of the Decapolis and the phenomenon in the Roman world. J. Roman Archaeol. 35, 107–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759421000465 Lichtenberger, A. (2021). The Decapolis, in: A Companion to the Hellenistic and Roman Near East. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119037354.ch18 Makhadmeh, A., Al-Badarneh, M., Rawashdeh, A. and Al-Shorman, A. (2020). Evaluating the carrying capacity at the archaeological site of Jerash (Gerasa) using mathematical GIS modeling. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 23, 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrs.2018.09.002 Shiyab, A., Al-Shorman, A., Turshan, N., Tarboush, M., Alawneh, F. and Rahabneh, A. (2019). Investigation of late Roman pottery from Gadara of the Decapolis, Jordan using multi-methodic approach. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 25, 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.04.003 | Raphana of the Decapolis and its successor Arpha - The search for an eminent Greco-Roman City | Jens Kleb | <p style="text-align: justify;">This research paper presents a detailed analysis of ancient literature and archaeological and geographical research until the present day for an important ancient location in the southern part of Syria. This one had... |  | Landscape archaeology, Mediterranean, Spatial analysis, Theoretical archaeology | Luc Doyon | 2021-12-30 13:54:32 | View | |

03 Feb 2024

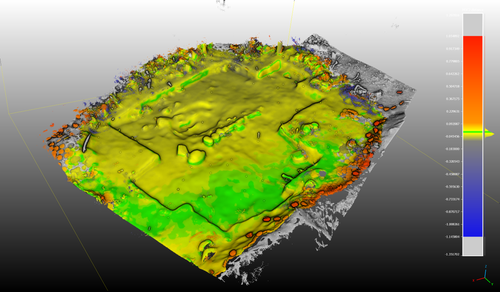

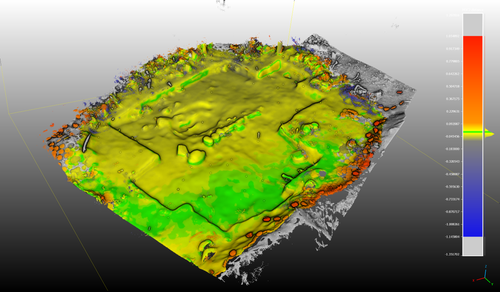

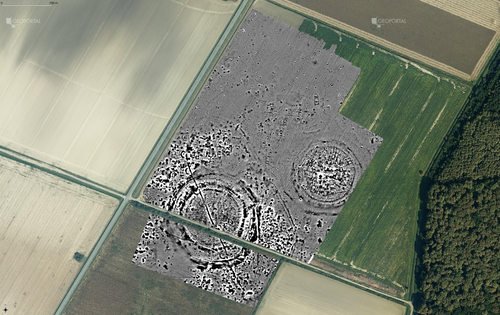

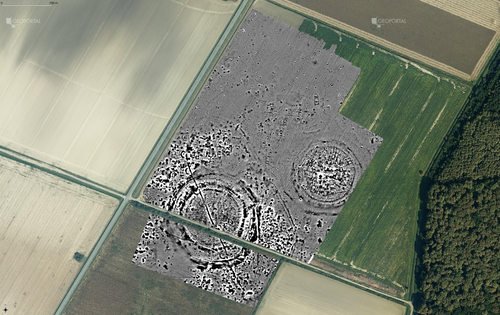

Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern CroatiaSosic Klindzic Rajna; Vuković Miroslav; Kalafatić Hrvoje; Šiljeg Bartul https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970703What lies on top lies also beneath? Connecting crop surface modelling to buried archaeology mapping.Recommended by Markos Katsianis based on reviews by Ian Moffat and Geert Verhoeven based on reviews by Ian Moffat and Geert Verhoeven

This paper (Sosic et al. 2024) explores the Neolithic landscape of the Sopot culture in Đakovština, Eastern Slavonija, revealing a network of settlements through a multi-faceted approach that combines aerial archaeology, magnetometry, excavation, and field survey. This strategy facilitates scalable research tailored to the particularities of each site and allows for improved representations of buried archaeology with minimal intrusion. Using the site of Tomašanci-Dubrava as an example of the overall approach, the study further explores the use of drone imagery for 3D surface modeling, revealing a consistent correlation between crop surface elevation during full plant growth and ground terrain after ploughing, attributed to subsurface archaeological features. Results are correlated with magnetic survey and test-pitting data to validate the micro-topography and clarify the relationship between different subsurface structures. The results obtained are presented in a comprehensive way, including their source data, and are contextualized in relation to conventional cropmark detection approaches and expectations. I found this aspect very interesting, since the crop surface and terrain models contradict typical or textbook examples of cropmark detection, where the vegetation is projected to appear higher in ditches and lower in areas with buried archaeology (Renfrew & Bahn 2016, 82). Regardless, the findings suggest the potential for broader applications of crop surface or canopy height modelling in landscape wide surveys, utilizing ALS data or aerial photographs. It seems then that the authors make a valid argument for a layered approach in landscape-based site detection, where aerial imagery can be used to accurately map the topography of areas of interest, which can then be further examined at site scale using more demanding methods, such as geophysical survey and excavation. This scalability enhances the research's relevance in broader archaeological and geographical contexts and renders it a useful example in site detection and landscape-scale mapping. References Renfrew, C. and Bahn, P. (2016). Archaeology: theories, methods and practice. Thames and Hudson. Sosic Klindzic, R., Vuković, M., Kalafatić, H. and Šiljeg, B. (2024). Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern Croatia, Zenodo, 7970703, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7970703 | Digital surface models of crops used in archaeological feature detection – a case study of Late Neolithic site Tomašanci-Dubrava in Eastern Croatia | Sosic Klindzic Rajna; Vuković Miroslav; Kalafatić Hrvoje; Šiljeg Bartul | <p>This paper presents the results of a study on the neolithic landscape of the Sopot culture in the area of Đakovština in Eastern Slavonija. A vast network of settlements was uncovered using aerial archaeology, which was further confirmed and chr... |  | Landscape archaeology, Neolithic, Remote sensing, Spatial analysis | Markos Katsianis | 2023-09-01 12:57:04 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

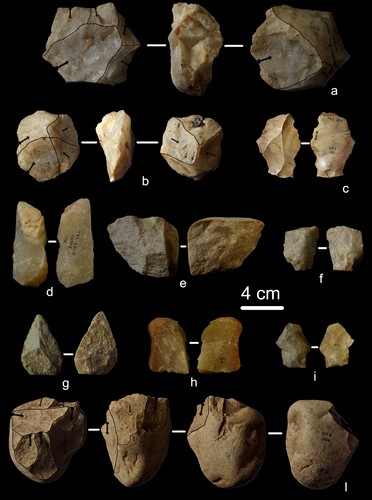

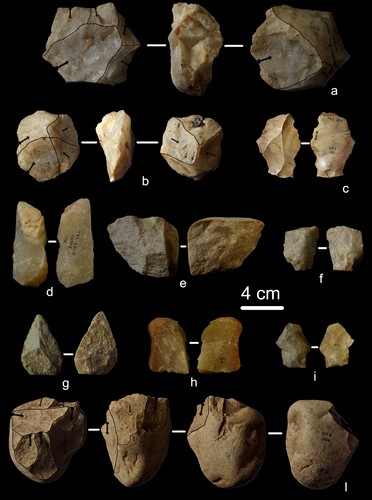

First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy)Sara Daffara, Carlo Giraudi, Gabriele L.F. Berruti, Sandro Caracausi, Francesca Garanzini https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4ufNot Simply the Surface: Manifesting Meaning in What Lies Above.Recommended by Marcel Kornfeld based on reviews by Lawrence Todd, Jason LaBelle and 2 anonymous reviewersThe archaeological record comes in many forms. Some, such as buried sites from volcanic eruptions or other abrupt sedimentary phenomena are perhaps the only ones that leave relatively clean snapshots of moments in the past. And even in those cases time is compressed. Much, if not all other archaeological record is a messy affair. Things, whatever those things may be, artifacts or construction works (i.e., features), moved, modified, destroyed, warped and in a myriad of ways modified from their behavioral contexts. Do we at some point say the record is worthless? Not worth the effort or continuing investigation. Perhaps sometimes this may be justified, but as Daffara and colleagues show, heavily impacted archaeological remains can give us clues and important information about the past. Thoughtful and careful prehistorians can make significant contributions from what appear to be poor archaeological records. In the case of Daffara and colleagues, a number of important theoretical cross-sections can be recognized. For a long time surface archaeology was thought of simply as a way of getting a preliminary peak at the subsurface. From some of the earliest professional archaeologists (e.g., Kidder 1924, 1931; Nelson 1916) to the New Archaeologists of the 1960s, the link between the surface and subsurface was only improved in precision and systematization (Binford et al. 1970). However, at Hatchery West Binford and colleagues not only showed that surface material can be used more reliably to get at the subsurface, but that substantive behavioral inferences can be made with the archaeological record visible on the surface. Much more important are the behavioral implications drawn from surface material. I am not sure we can cite the first attempts at interpreting prehistory from the surface manifestations of the archaeological record, but a flurry of such approaches proliferated in the 1970s and beyond (Dunnell and Dancey 1983; Ebert 1992; Foley 1981). Off-site archaeology, non-site archaeology, later morphing into landscape archaeology all deal strictly with surface archaeological record to aid in understanding the past. With the current paper, Daffara and colleagues (2024) are clearly in this camp. Although still not widely accepted, it is clear that some behaviors (parts of systems) can only be approached from surface archaeological record. It is very unlikely that a future archaeologist will be able to excavate an entire human social/cultural system; people moving from season to season, creating multiple long and short term camps, travelling, procuring resources, etc. To excavate an entire system one would need to excavate 20,000 km2 or some similarly impossible task. Even if it was physically possible to excavate such an enormous area, it is very likely that some of contextual elements of any such system will be surface manifestations. Without belaboring the point, surface archaeological record yields data like any other archaeological record. We must contextual the archaeological artifacts or features weather they come from surface or below. Daffara and colleagues show us that we can learn about deep prehistory of northern Italy, with collections that were unsystematically collected, biased by agricultural as well as other land deformations agents. They carefully describe the regional prehistory as we know it, in particular specific well documented sites and assemblages as a means of applying such knowledge to less well controlled or uncontrolled collections.

References Binford, L., Binford, R. S. R., Whallon, R. and Hardin, M. A. (1970). Archaeology of Hatchery West. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, No. 24, Washington D.C. Daffara, S., Giraudi, C., Berruti, G. L. F., Caracausi, S. and Garanzini, F. (2024). First evidence of a Palaeolithic frequentation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy), OSF Preprints, pz4uf, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4uf Dunnell, R. C. and Dancey, W. S. (1983). The siteless survey: a regional scale data collection strategy. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 6, edited by Michael B. Schiffer, pp. 267-287. Academic Press, New York. Ebert, J. I. (1992). Distributional Archaeology. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. Foley, R. A. (1981). Off site archaeology and human adaptation in eastern Africa: An analysis of regional artefact density in the Amboseli, Southern Kenya. British Archaeological Reports International Series 97. Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 3. Oxford England. Kidder, A. V. (1924). An Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology, With a Preliminary Account of the Excavations at Pecos. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy, no. 1. New Haven, Connecticut. Kidder, A. V. (1931). The Pottery of Pecos, vol. 1. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy. New Haven, Connecticut. Nelson, N. (1916). Chronology of the Tano Ruins, New Mexico. American Anthropologist 18(2):159-180. | First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy) | Sara Daffara, Carlo Giraudi, Gabriele L.F. Berruti, Sandro Caracausi, Francesca Garanzini | <p>The Trino hill is an isolated relief located in north-western Italy, close to Trino municipality. The hill was subject of multidisciplinary studies during the 1970s, when, because of quarrying and agricultural activities, five concentrations of... |  | Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic | Marcel Kornfeld | 2023-10-04 16:58:19 | View | |

26 Oct 2022

Technological analysis and experimental reproduction of the techniques of perforation of quartz beads from the Ceramic period in the AntillesMadeleine Raymond, Pierrick Fouéré, Ronan Ledevin, Yannick Lefrais and Alain Queffelec https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/a5tgpUsing Cactus Thorns to Drill Quartz: A Proof of ConceptRecommended by Donatella Usai and Jonathan Hanna based on reviews by Viola Stefano, ? and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Viola Stefano, ? and 1 anonymous reviewer

Quartz adornments (beads, pendants, etc.) are frequent artifacts found in the Caribbean, particularly from Early Ceramic Age contexts (~500 BC-AD 700). As a form of specialization, these are sometimes seen as indicative of greater social complexity and craftsmanship during this time. Indeed, ethnographic analogy has purported that such stone adornments require enormous inputs of time and labor, as well as some technological sophistication with tools hard-enough to create the holes (e.g., metal or diamonds). However, given these limitations, one would expect unfinished beads to be a common artifact in the archaeological record. Yet, whereas unworked/raw materials are often found, beads with partial/unfinished perforations are not. References:

| Technological analysis and experimental reproduction of the techniques of perforation of quartz beads from the Ceramic period in the Antilles | Madeleine Raymond, Pierrick Fouéré, Ronan Ledevin, Yannick Lefrais and Alain Queffelec | <p style="text-align: justify;">Personal ornaments are a very specific kind of material production in human societies and are particularly valuable artifacts for the archaeologist seeking to understand past societies. In the Caribbean, Early Ceram... |  | Lithic technology, Neolithic, South America, Symbolic behaviours, Traceology | Donatella Usai | 2022-09-06 14:01:51 | View | |

28 Feb 2021

A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic AgeAlain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/7dq3b/Open data on beads, pendants, blanks from the Ceramic Age CaribbeanRecommended by Ben Marwick based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang

The paper 'A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age' by Queffelec et al. [1] presents a description of a dataset of nearly 5000 lapidary artefacts from over 100 sites. The data are dominated by beads and pendants, which are mostly made from Diorite, Turquoise, Carnelian, Amethyst, and Serpentine. The raw material data is especially valuable as many of these are not locally available on the island. This holds great potential for exchange network analysis. The data may be especially useful for investigating one of the fundamental questions of this region: whether the Cedrosan and Huecan are separate, little related developments, with different origins, or variants or a single tradition [2]. In addition to metric and technological details about the artefacts, the data include a variety of locational details, including coordinates, distance to coast, and altitude. This enables many opportunities for future spatial analysis and geostatistical modelling to understand human behaviours relating to ornament production, use, and discard. I recommend the authors make a minor revision to Table 1 (spatial coverage of the dataset) to make the column with the citations conform to the same citation style used in the rest of the text. I warmly commend the authors for making transparency and reproducibility a priority when preparing their manuscript. Their use of the R Markdown format for writing reproducible, dynamic documents [3] is highly impressive. This is an excellent example for others in the international archaeological science community to follow. The paper is especially useful for researchers who are new to R and R Markdown because of the elegant and accessible way the authors document their research here. [1] Queffelec, A., Fouéré, P. and Caverne, J.-B. 2021. A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age. SocArXiv, 7dq3b, ver. 4 Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/7dq3b [2] Reed, J. A. and Petersen, J. B. 2001. A comparison of Huecan and Cedrosan Saladoid ceramics at the Trants site, Montserrat. In Proceedings of the XVIIIth International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology (pp. 253-267). [3] Marwick, B. 2017. Computational Reproducibility in Archaeological Research: Basic Principles and a Case Study of Their Implementation. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24, 424–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-015-9272-9 | A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age | Alain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne | <p>Lapidary artifacts show an impressive abundance and diversity during the Ceramic period in the Caribbean islands, especially at the beginning of this period. Most of the raw materials used in this production do not exist naturally on the island... |  | Neolithic, North America, Raw materials, South America, Spatial analysis, Symbolic behaviours | Ben Marwick | 2020-11-13 23:52:34 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer