The “Beast Within” – Querying the (Cultural Evolutionary) Status of Types in Archaeology

, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak

, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Edward B. Banning and 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Edward B. Banning and 2 anonymous reviewers

The Physics and Metaphysics of Classification in Archaeology

Abstract

Recommendation: posted 04 December 2024, validated 31 December 2024

Hussain, S., Riede, F. and Plutniak, S. (2024) The “Beast Within” – Querying the (Cultural Evolutionary) Status of Types in Archaeology. Peer Community in Archaeology, 100318. 10.24072/pci.archaeo.100318

Recommendation

“On the Physics and Metaphysics of Classification in Archaeology” by M. Okumura and A.G.M. Araujo (1) is a welcome contribution to our upcoming edited volume on type-thinking and the uses and misuses of archaeological typologies. Questions of type-delineation and classification of archaeological materials have recently re-emerged as key arenas of scholarly attention and interrogation (2–4), as many researchers have turned to a matured field of cultural evolutionary studies (5–7) and as fine-grained archaeological data and novel computational-quantitative methods have becomes increasingly available in recent years (8, 9). Re-assessing the utility and significance of traditional archaeological types has also become pertinent as macro-scale approaches to the past have grown progressive to the centre of the discipline (10, 11), promising not only to ‘re-do’ typology ‘from the ground up’, but also to put types and typological systems to novel and powerful use, and in the process illuminate the many understudied large-scale dynamics of human cultural evolution which are so critical to understanding our species’ venture on this planet. As such, the promise is colossal yet it requires a solid analytical base, as many have insisted (e.g., 12). Types are often identified as such foundational analytical units, and much therefore hinges on the robust identification and differentiation of types within the archaeological record. Typo-praxis – the practice of delineating and constructing types and to harness them to learn about the archaeological record – is therefore also increasingly seen as a key ingredient of what Hussain and Soressi (13) have dubbed the ‘basic science’ claim of lithic research within human origins or broader (deep-time) evolutionary studies.

The stakes are accordingly incredibly high, yet as Okumura and Araujo point out there is still no need to ‘re-invent the wheel’ as there is a rich literature on classification and systematics in the biological sciences, from which archaeologists can draw and benefit. Some of this literature was indeed already referenced by some archaeologists between the 1960s and early 2000s when first attempts were undertaken to integrate Darwinian evolutionary theory into processual archaeological practice (14, 15). It may be argued that much of this literature and its insights – including its many conceptual and terminological clarifications – have been forgotten or sidelined in archaeology primarily because the field has witnessed a pronounced ‘cultural turn’ beginning in the early 2000s, with even processualists expanding their research portfolio to include what was previously considered post-processual terrain (16, 17). Michelle Hegmon’s (16) ‘processualism plus’ was perhaps the most emphatic expression of this trajectory within the influential Anglo-American segments of the profession. Okumura and Araujo are therefore to be applauded for their attempt to draw attention again to this literature in an effort to re-activate it for contemporary research efforts at the intersection of cultural evolutionary and computational archaeology. Decisions need to be made on the way, of course, and the authors defend a theory-guided (and largely theory-driven) approach, for example insisting on the importance of understanding the metaphysical status of types as arbitrary kinds. Their chapter is hence also a contribution (some may say intervention) to the long-standing tension between the tyranny of data vs. the tyranny of theory in type-construction. They clearly take side with those who argue that typo-praxis cannot evade its metaphysical nature – i.e., it will always be concerned (to some extent at least) with uncovering basic metaphysical principles of the world, even if the link between types and world is not understood as a simple mapping function. Carving the investigated archaeological realities ‘at their joints’ remains an overarching ambition from this perspective. Following Okumura and Araujo, archaeologists interested in these matters therefore cannot avoid to become part-time metaphysicians.

Okumura and Araujo’s contribution is timely and it brings key issues of debate to archaeological attention, and many of these issues tellingly overlap substantially with foundational debates in the philosophy of science (e.g. monism vs. pluralism, essentialism vs. functionalism, and so forth). Their chapter also showcases how critical (both in an enabling and limiting way) biological metaphors such as ‘species’ are (see esp. the discussion of ‘species as sets’ vs. ‘species as individuals’) for their and cognate projects. Whether such metaphors are justified in the context of human action is a longstanding point of contention, and other archaeologies – for example those with decidedly relational, ontological, and post-humanist aspirations – have developed very different optics (see e.g. 18, esp. Chapter 6). This being said, Okumura and Araujo’s contribution will be essential for those interested in (re-)learning about the ‘physics and metaphysics’ of archaeological classification and their chapter will be an excellent place to start with such engagement.

References

1. M. Okumura and A. G. M. Araujo (2024) The Physics and Metaphysics of Classification in Archaeology. Zenodo, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7515797

2. F. Riede (2017) “The ‘Bromme problem’ – notes on understanding the Federmessergruppen and Bromme culture occupation in southern Scandinavia during the Allerød and early Younger Dryas chronozones” in Problems in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Research, pp. 61–85.

3. N. Reynolds and F. Riede (2019) House of cards: cultural taxonomy and the study of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Antiquity 93, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.49

4. R. L. Lyman (2021) On the Importance of Systematics to Archaeological Research: the Covariation of Typological Diversity and Morphological Disparity. J Paleo Arch 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00077-6

5. A. Mesoudi (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences, University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/9780226520452

6. N. Creanza, O. Kolodny and M. W. Feldman (2017) Cultural evolutionary theory: How culture evolves and why it matters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 7782–7789. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620732114

7. R. Boyd and P. J. Richerson (2024) Cultural evolution: Where we have been and where we are going (maybe). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, e2322879121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2322879121

8. F. Riede, D. N. Matzig, M. Biard, P. Crombé, J. F.-L. de Pablo, F. Fontana, D. Groß, T. Hess, M. Langlais, L. Mevel, W. Mills, M. Moník, N. Naudinot, C. Posch, T. Rimkus, D. Stefański, H. Vandendriessche and S. T. Hussain (2024) A quantitative analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe. PLOS ONE 19, e0299512, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299512

9. L. Fogarty, A. Kandler, N. Creanza and M. W. Feldman (2024) Half a century of quantitative cultural evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, e2418106121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2418106121

10. A. M. Prentiss, M. J. Walsh, E. Gjesfjeld, M. Denis and T. A. Foor (2022) Cultural macroevolution in the middle to late Holocene Arctic of east Siberia and north America. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 65, 101388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101388

11. C. Perreault (2023) Guest Editorial. Antiquity 97, 1369–1380.

12. F. Riede, C. Hoggard and S. Shennan (2019) Reconciling material cultures in archaeology with genetic data requires robust cultural evolutionary taxonomies. Palgrave Commun 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0260-7

13. S. T. Hussain and M. Soressi (2021) The Technological Condition of Human Evolution: Lithic Studies as Basic Science. J Paleo Arch 4, 25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00098-1

14. R. C. Dunnell (1978) Style and Function: A Fundamental Dichotomy. American Antiquity 43, 192–202.

15. R. C. Dunnell (2002) Systematics in Prehistory, Illustrated Edition, The Blackburn Press.

16. M. Hegmon (2003) Setting Theoretical Egos Aside: Issues and Theory in North American Archaeology. American Antiquity 68, 213–243. https://doi.org/10.2307/3557078

17. R. Torrence (2001) “Hunter-gatherer technology: macro- and microscale approaches” in Hunter-Gatherers: An Interdisciplinary Perspective, Cambridge University Press.

18. C. N. Cipolla, R. Crellin and O. J. T. Harris (2024) Archaeology for today and tomorrow, Routledge.

The recommender in charge of the evaluation of the article and the reviewers declared that they have no conflict of interest (as defined in the code of conduct of PCI) with the authors or with the content of the article. The authors declared that they comply with the PCI rule of having no financial conflicts of interest in relation to the content of the article.

Fapesp

Evaluation round #2

DOI or URL of the preprint: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10633062

Version of the preprint: 2

Author's Reply, 08 Nov 2024

To whom it may concern

We are sending a revised version of the manuscript.

The main changes are related to the general structure of the draft: the general discussion and the biological examples were merged in a single section, many parts of the manucript which were not important for the general discussion were deleted, the manuscript has now subtitles and (hopefully) smooth transitions from one topic to another and we clearly support a given classification and kind to be applied when studying archaeological materials, providing the reader with the reasons why we defend such position.

We would like to sincerely thank the reviewers for they careful reading and they insightful ideas. We believe that this draft is a much better (clearer, concise, better written) version of the original manuscript and this certainly would not be possible without the reviewers' efforts to help us improving our book chapter.

Kind regards

Mercedes and Astolfo

Decision by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak

, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , posted 22 Mar 2024, validated 22 Mar 2024

, posted 22 Mar 2024, validated 22 Mar 2024

Dear authors,

I have decided to send your paper for another round of reviews and the reviewer's comments are now available (see below).

As you can see, all reviewers appreciate the changes you have made but also rise a few addtional points you should consider and address when finalizing your chapter.

In addition, I kindly want to draw your attention to some of my own concerns regarding the philosophy-of-science part of your chapter and notably some of the more specific statements and inferences you make there (see my attached in-text comments).

In light of these and earlier review comments, I would generally recommend to:

- work on some of your transitions between subsections in the first part of your paper as there are recurrent jumps in thematic/conceptual/argumentative focus, which really make it hard for the reader to follow your train of thought and to retain focus

- perhaps add additional subheadings to do so

- add much clearer statements both in the introdcution and conclusion about the main arguments of your paper and what the "take-home message" is (this take-home message should also appear in the abstract of course)

- add a "teaster" or "roadmap"-like section to your introduction where you clearly lay out the structure of the paper and why the different section steps are taken, so that the reader is prepared for what is to come, and, importantly, why these steps are necessary to take.

- seriously consider re-organization of your structure: parts 1 and 2 of your chapter may benefit from some condensation (there is significant reduncancy at times for example) and it may moreoever be advisable to move part 3 to the beginning as this is a paper about archaeology after all (you may then even consider to integrate parts 1 and 2 into this larger "Metaphysics of Archaeology" section as engaging with such topics raises questions and brings in parallel discussions from biology etc.; it may also help you with more effectively focalizing the notion of "classification" from the get go as this is really should be core topic of your chapter)

- amend capitalization issues throughout (archaeology, not Archaeology; biological sciences, not Biological Sciences, etc.)

I hope all of this makes sense to you.

We look forward to your finalised chapter,

Shumon

Download recommender's annotations

Reviewed by anonymous reviewer 2, 13 Mar 2024

I thank the authors for the reply to my comments, for adding an abstract and for clarifying the scope of the paper. I am only adding two additional comments based on the changes you have made and your reply.

Thank you for the added section on monothetic vs polythetic groups, which I think is very useful. I do not have access to the figures you mention - which unless I am mistaken are not included in the zenodo file.

You seem to advocate a switch from polythetic to monothetic groups, which is a discussion already very well present in recent archaeological literature (without being explicitly addressed in these terms, which is why this section of the paper is particularly useful). However, I believe it would be useful as well to include a discussion of why polythetic groups were adopted in the first place (why were they considered more "natural" p. 28) and of the impact of the use of polythetic vs monothetic groups on the type of questions asked by archaeologists? Both aspects (why polythetic/monothetic groups are used in the first place and the consequences of their uses for comparative analyses) are intermingled and could perhaps be treated separately. Perhaps using the information on the section on "Metaphysics of Classification in Biology" here could also clarify these points.

Your reply stating that "We maintain that the search for conventional types is a dead

end." Or, in the text, p. 20 "Conventional kinds are, of course, extremely important for the cultural systems who implemented them, but their importance dies with the people who created, used, and believed in them." These strong statements seem to be directly related to the emic vs etic debate, as well as to the theoretical approches used. The article is already quite long as is but I believe it would have benefited from more explanations regarding this.

Reviewed by anonymous reviewer 1, 22 Feb 2024

I’ve read the revised version and, in my opinion, the authors have responded adequately and appropriately to all my comments in version #1. I, therefore, recommend publication.

Reviewed by Edward B. Banning , 15 Feb 2024

, 15 Feb 2024

Overall, I found this a really interesting and compelling paper, and I recommend its publication.

Although I do not necessarily agree with all the points made in this paper, I still find that you've made a compelling argument, and I see the value in considering both the historical/metaphysical roots of the classification/categorization problems and the parallels between similar issues in Biology and Archaeology, something that I would agree most archaeologists who have previously dealt with these issues have largely overlooked.

Almost all my more detailed comments, in fact, are purely editorial in nature. I have made detailed editorial suggestions, mostly for clarity, grammar and style. I would also suggest making changes to the abstract (abstracts should always summarize the paper, including its conclusions, not just introduce the topic), and you might consider a certain amount of reorganization and shortening of the manuscript. As I am quite interested in this topic, I read it eagerly, but some readers might be put off by the fact that the manuscript is rather lengthy and arguably the narrative wanders a bit, especially in the second half, despite the excellent use of subheadings to clarify the structure.

My much pickier and minor editorial comments are marked up in tracking on the attached version of the manuscript.

Download the reviewEvaluation round #1

DOI or URL of the preprint: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7515798

Version of the preprint: 1

Author's Reply, 08 Feb 2024

Decision by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak

, Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , posted 15 Mar 2023, validated 15 Mar 2023

, posted 15 Mar 2023, validated 15 Mar 2023

Dear authors,

many thanks for going along with our PCI-based review and revision process. As you will see from the reviewers' comments, your chapter is considered of potential value for revisiting and steering important foundational debates on classification in archaeology.

As you will see from the reviewers comments’ below, both reviewers identify more convincing and less convincing parts of the paper and make a number of important observations and recommendations. Both reviewers have some issues with the overall coherence and structure of the argumentation, however, and this is one of the main aspects that I would recommend carefully addressing in the revisions.

Another central issue is the often selective and one-sided choice of reference literature highlighted by the reviewers, especially with regard to the current state of the debate on classification, typology and systematics in archaeology itself. This may in part have something to do with the fact that given the current outline, the reader is somewhat thrown into the swamp of plentiful concepts and discussion points without clear guidance what to expect and what to follow/pay attention to. In other words, a proper introduction seems currently missing where the overarching goals of the contribution and the core arguments are explicitly introduced, framed and specified. This may also help in defusing the essayistic character of the contribution, which is not in itself a problem but leaves at times the impression of compilatory meandering rather than a focused argument-driven discussion.

In addition to the reviewers’ perceptive suggestions, I also recommend that key concepts are more explicitly and carefully defined (and not really needed concepts removed from the manuscript altogether). Already the term ‘Metaphysics’ remains poorly defined and its relationship to concepts such as ‘epistemology’ and ‘ontology’ (both used in the text) not well articulated (I suggest to consult Corbey 2005, The Metaphysics of Apes: Negotiating the Animal-Human Boundary here). Personally, I regard the possibility of the metaphysical independence of scientific endeavors as a straw-man since nobody really takes, inhabits or defends this position anymore, and both the history and philosophy of science and modern science studies have sufficiently established that there simply can be no ‘outside’ of metaphysics broadly construed. Also because of this latter point, some distinctions such as ‘descriptive’ vs. ‘prescriptive’ metaphysics are minimally confusing to me (as if metaphysics would be a praxis that one could explicitly engage in). Another example is the distinction between ‘natural’, ‘conventional’ and ‘arbitrary’ kinds. The difference between the latter two is not clear at all as one can ask whether arbitrary kinds would not simply defeat themselves and are as such no kinds at all (or is the point here that these are kinds not shared within communities but rather recovered by individuals?). Minimally, and the reviewers have remarked on this as well, these debates invite references to influential conversations in archaeology and anthropology such as the ‘emic’ vs. ‘etic’ distinction. I find it generally confusing that some of the aforementioned key concepts are introduced and discussed at length only to be discarded at the end ('pure observation' is another candidate), at least this is how I understand some of the points made. It would thus be good, in the grand to scheme of things, to review all of this and to balance the discussion better in terms of argumentative relevance.

Another definitional note: ‘classification’ should probably already in the very beginning be contrasted with ‘categorization’ as both are ordering practices but do not necessarily denote the same – and also because the two concepts may be differentially relevant for the other concepts discussed (including the discussion of 'kinds'). This would help to clarify the text and the points made.

The elephant in the room, of course, is how such debates can inform our selection of observations (properties, qualities, traits, etc.) on which to base classificatory systems. As you remark yourself on p. 21 “Archaeologists under the Evolutionary Archaeology approach would mostly agree that qualitative similarity can indicate causal relations among elements and such relations (which are theory-based) are essential to create explanations about the evolutionary history of artifact lineages” but I would say the whole question here is ultimately not about theory-ladeness (which is widely accepted) but rather how such background theory informs concrete property/trait choice, and this is well illustrated by phylogenetic approaches, which commonly foreground functional traits. These discussions are obviously complex (see my comment on lithic stem shapes below) and should be portrayed as such. Jung (2020) for example suggests rather explicitly that a traditional focus on form in archaeological typology should be complemented by newer consideration on function and affordance. This brings me back to an important point touched upon earlier: it is currently somewhat unclear, or is drowned in the breadth of discussion and conceptual debate, what precisely your paper wants to contribute to, and I would recommend to clarify this focus and sharpen it substantially throughout. This would also include a clearer discussion/exposition of the implications of the more philosophical considerations reviewed for archaeological practice and their integration into the relevant archaeological debates, some of which are currently largely ignored. Alternatively, you may want to specify from the onset what specific archaeology you wish to target and focus on in your discussion of classsifcatory practice.

I paste a few specific comments on some statements that I stumbled upon when reading the text below, as these may help in address some of these issues.

In total, I believe this could be a really important and insightful contribution to our planned volume – so thanks again for your trust and submission!

I look forward to seeing your revised version in due time.

Best wishes,

Shumon

p. 11: “The historical approach states that causal relations are fundamental, and that qualitative similarity is important when it can help pointing to causal connections (Ereshefsky 2001: 28).” – I am uncertain what is meant by ‘causal’ here and this needs to be specified; causality can mean many things and may even be misleading in this context. I assume ‘genealogical relationships’ is what is pointed at here. Also note that even the recognition of causal relations does not necessarily solve the problem of identifying the properties that are causally relevant, the elephant in the room (see other comments).

p. 12: “Such pluralistic approach does not necessarily need to be associated to realist or antirealist views of science (meaning that one can use a pluralistic approach without having to agree whether or not science will provide better theories that explain the world).” The latter is a mischaracterization of scientific realism and pluralism.

p. 14: “Very few authors have discussed the philosophy of classification in Archaeology.” – check out at least the work of Alison Wylie (2002), Philippe Boissinot (2015) and Mathias Jung (2020), as well as Susan Pollock and Reinhard Bernbeck (2005) on categorization.

p. 14 “Even worse has been the lack of discussion regarding a metaphysics of artifacts: an account of what sorts of things they are, and into what ontological category they would fit” – there is whole body of literature in archaeology on things and objects, with key people such as Bjørnar Olsen and sometimes dubbed the ‘material turn’ where the ontological status of things and artefacts are explicitly queried.

p. 16 “If we assume that classifications are always and inescapably theory19-laden, and this is by itself a metaphysical position,” – why is this? Would the other ‘metaphysical position’ then be that classifications are theory-free? How would this make sense?

p. 16 “In the case of Evolutionary Archaeology, which states that artifacts represent evolutionary lineages created by cultural transmission” – if EA takes this as its starting point, something is wrong; statements like this have to be nuanced and qualified.

p. 17: “Some archaeologists explicitly reject the idea that classification in Archaeology ought to “discover” these natural kinds (Adams & Adams 1991: 13; Dunnell 1986: 177-182; Dunnell 2009: 47), while others explicitly put the ultimate goal of classification as the discovery of types (Spaulding 1953), or at least a quest for the reconstruction of the mental templates of the artisans (Read 2007).” – the latter two are concepts arguably not equitable to natural kinds and the resp. authors would also not necessarily subscribe to ‘natural kinds’. This is very oddly phrased as I am not aware of anybody in archaeology actually aiming to uncover ‘natural kinds’.

p. 17: “In this realm, Archaeology departs from Biology because the latter is occupied with the classification of natural things, and the question of natural kinds can be legitimate, while Archaeology is tackling with the fact that artifacts are created by humans.” – This reintroduces the nature-culture dichotomy on the metaphysical level. So artifacts are not part of the natural world and they do not partake in the ‘natural order’? I would say this rendering misses the point of the ‘natural kind’ debate. It would indeed be good if the authors provide some more rationale why this debate even matters, especially given that they reject it themselves at the end for archaeology (but this whole argument arguably needs to be revisited).

p. 21: “The problem is that when performing a typology, the researcher is skipping the analytic step, since a type is already a synthetic unit (Araujo and Okumura 2021).” – be aware that archaeologists (and other scholars) have in the past routinely distinguished between ‘monothetic’ and ‘synthetic’ type concepts (e.g. Hahn, McPherron)

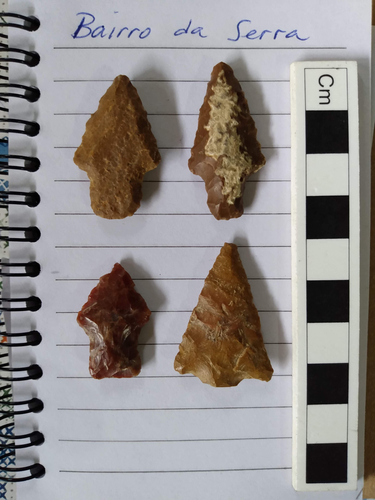

p. 23: “In the case of a classification of arrowheads, under an Evolutionary Archaeology approach, the stem shape can be considered as related to stylistic choices that are considered as very little associated to the actual performance of the point (meaning that a point presenting a concave stem base might be as good as a point that has a bifurcated stem shape” – in many cases the configuration of the stem may actually be more importance for the overall functionality/operationality of the weapon system, in the sense of its ‘performance qualities’, as the stem connects the point with the haft and is therefore a key design element in integrating the whole system. See Steven Kuhn’s (2020) useful discussion of different hafting solutions in relation to different proximal artefact designs and its relevance in long-term technological evolution. This qualification, in other words, relies on a restricted definition of performance. Also, I think we should not prematurely transition here from the debate on ‘natural’ and ‘conventional’ kinds to the old (archaeological) debate on ‘function’ vs. ‘style’, not least because the latter has not necessarily clarified things and the relation between the two debates is not obvious and everything else than intuitively given.

Reviewed by anonymous reviewer 1, 14 Mar 2023

I paginated the pdf to make it easier to comment. I highly recommend doing this, and numbering the lines in the whole document. I should mention that I am a paleoanthropologist and an archaeologist, not a philosopher or an historian of science.

___________________________________________________________________

The manuscript consists of 3 parts: (1) a discussion of metaphysics and classification in philosophy of science (pp. 1-7), (2) how these terms and concepts are used in biology (pp. 8-13), and (3) how (2) can be applied to archaeology (pp. 14-25).

(1) is quite sophisticated but replete with terms and concepts unfamiliar to most archaeologists or defined differently from archaeological usage. The authors note that epistemology is largely ignored by archaeologists, which is true (and also true of biologists). The text reads much longer and more complex than it has to be, assuming that the target audiences are biologists and archaeologists. It could benefit from stringent copy editing. It needs more headings to break it up into manageable chunks, and some figures summarizing the main points made in the text. It appears to have been written for philosophers or historians of science. It is the strongest part of the essay.

(2) is more comprehensible to someone like me, an archaeologist with a background in human paleontology. This means the logic of inference is more readily understood, as are the concepts and terms (although “The species-as-sets approach can be tentatively compared to species as mereological sums – the grouping of objects under the parthood relation – which are also defined by their extensions, in the same way that sets are” (pg. 10) must be amongst the most jargon-ridden sentences in the English language!) I’ve read some of the authors cited (e.g., Richards, Ghiselin, Boyd, Gould, Ereshefsky) because I taught a graduate seminar on evolutionary epistemology. Based on that, (2) basically made sense. It however relies rather too heavily on Richards and ignores Hahlweg, Hooker, Casti, Hull, etc.

(3) is the weakest of the three sections. It offers only a very dated and selective construal of anglophone archaeology, and fails to even mention the francophone research tradition that dominated Stone Age archaeology world-wide for more than a century. It was only in the 1970s that anglophone archaeology shed culture history, now seen as strictly empiricist (. . “the facts speak for themselves”), limited in its ability to explain anything of interest and shot through with all kinds of simplistic, essentialist, variety-minimizing assumptions about ‘culture’, the nature of change, and hunter-gatherer adaptations. This shift in the conceptual foundation of the discipline took place when I was in graduate school. It was wrought by Binford, Flannery and their intellectual progeny (Longacre, Hill, Dibble, Schiffer, Freeman, etc.). Dunnell was important, as they note, but his impact on the field was limited by his book, Systematics in Prehistory (1971), quite possibly the most boring text ever written. After that he was largely ignored. This part of the manuscript should be thoroughly updated and revised. There are few citations and most of them date in the 1940s-1960s. Anglophone archaeology has changed radically in the past 20 years, although little of this is evident in this part of the manuscript. Archaeology has no universal metalanguage (i.e., mathematics) like physical science does, nor is it very introspective. Consequently, confusion in concepts and terms is inevitable both within, and between, intellectual traditions.

In sum, the manuscript does not cohere very well. (1) is complicated and abstruse to biologists and archaeologists, but probably relatively clear to historians of science. (2) looks pretty good to me because I have some control over systematics in biology. An archaeologist without a background in neo-Darwinian evolution would have trouble with it. (3) is a dated, selective view of archaeology that bears little resemblance to modern practice in the anglophone research tradition. Francophone researchers have also begun to contemplate the logic of inference underlying the culture historical approach. These changes directly affect how we explain pattern in the past.

***

Here are some in-text notes that I made while reading the manuscript (only up to page 5), for your possible interest:

pg. 2 – there are 7-8 definitions of ‘species’ in human paleontology [HP] (see Kimbel & Martin, 2013), point being that ‘species’ depends on how they are defined and whether or not there is a consensus in the discipline.

pg. 2 – essentialism no longer a part of HP research, although it figured prominently in the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, cladistic methodologies, common in HP after the early 1990s, do tend to minimize variation. This is because of the conviction that speciation only, or mainly, occurs because of genetic isolation (i.e., cladogenesis); anagenesis no longer taken seriously by many card-carrying cladists.

pg. 2 – the French archaeological research tradition dominated the field from the 19th century until the early 1960s. It relied upon archaeological index fossils (e.g., Aurignacian blades, lamelle Dufour, etc.) to identify what they thought were prehistoric ‘cultures’ analogous to the bands, tribes, linguistic groups known to us from ethnography – a viewpoint that’s absurd from an anglophone perspective (see Binford & Sabloff 1983, Clark 1993, Barton & Clark 2022). Between c. 1900 and the early 1960s, the French approach also dominated US archaeology (called ‘culture history’ in the anglophone world). CH depended on variety-minimizing essentialist perspectives. After 1960 and continuing to the present, essentialism no longer part of anglophone archaeology, having been replaced by various processual conceptual frameworks.

pg. 3 – There are many definitions of science. My favorite is “a collection of methods for evaluating the empirical sufficiency of knowledge claims about the world of sense experience” (Clark 2007: 60).

pg. 3 – I doubt any classification can be ‘free from theory’ (bias), whether it be explicit or not, and ‘pure observation’ is impossible.

pg. 4 – any generalization arrived at strictly by induction can be refuted, but if a deductive element is ‘built into’ it, it is amenable to testing – so Dupré is correct.

pg. 4 – as to Wittgenstein, in physical science there is a universal metalanguage (mathematics) but biology, although it has a powerful, overarching metaphysical paradigm (neo-Darwinian evolution), and archaeology (which doesn’t) both lack a metalanguage that would allow for universal communication, hypothesis formation and testing.

pg. 5 – re Richards, the conceptual framework of biology is evolution. Any explanation that runs counter to the basic tenets of NDE would be rejected by all biologists.

pg. 5 – numerical taxonomy (Dupré) has fallen out of favor in HP and in archaeology, although I’ve never understood why. Methodological fads permeate both fields.

pg. 5 – see Rose (1998) for excellent discussion of reductionism in biology.

pp. 5,6 – many life scientists define a species as a polythetic set of genetic or biochemical polymorphisms.

pg. 5 – strictly speaking, taxonomy is the study of classification, a distinction usually ignored by archaeologists.

_____________________________

Barton, C.M. & Clark, G.A. (2021). From artifacts to cultures: Technology, society,

and knowledge in the Upper Paleolithic. Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 4(1): 1-21.

Binford, L., and Sabloft, J. (1982). Paradigms, systcmatics and archaeology. Journal of Anthropological Research 38(1): 137-153.

Clark, G.A. (1993). Paradigms in science and archaeology. Journal of Archaeological Research 1(3): 203-234.

Clark, G.A. (2007). The flight from science and reason: evolution and creationism in contemporary American life. In Proceedings of the International Science Conference ‘Science in Archaeology’ (B. Harrison, ed.), pp. 60-80. Portland, OR: Institute for Archaeological Studies.

Kimbel, W.H. & Martin, L.B., eds. (2013). Species, species concepts and primate evolution. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

Rose, S. (1998). Lifelines–Biology Beyond Determinism. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Reviewed by anonymous reviewer 2, 21 Feb 2023

The article 'On the Physics and Metaphysics of Classification in Archaeology' by Mercedes Okumura and Astolfo G.M. Araujo gives a welcome perspective on one main issue that has been faced by archaeologists since the emergence of the field: how to classify the archaeological material.

The article is well structured and well written. It first discusses the theoretical concepts (or absence of) behind classification, before developing in more detail the metaphysics of classification in biology and finally discussing the philosophy of classification in archaeology. The authors depart from the statement that this topic has been little explored in archaeology and call for a raise of awareness of what lies behind any kind of classification in archaeology and for being explicit about their theoretical positions.

In particular, the discussion about classification in archaeology that falls into two different types of kinds, i.e., conventional kinds and arbitrary kinds appears important. I however believe this section should be developed and include references to debates that have marked the history of archaeology. One may think, to cite but a few recent examples, of the extensive discussion on this in Tostevin's 2012 Seeing Lithics (Chapter 3 and the discussion of the emic vs. the etic including in the context of the Bordes-Binford debate), or of the discussion on the differences between chaîne opératoire and reduction sequence in Hussain's 2019 The French-Anglophone Divide in lithic research. The strong criticism that follows, of classifications based on conventional kinds, following Read's definition of an artefact as an intentionaly made object also reads like a simplification of the debate, as I wonder to what extent this restricted definition for artefact is used, even in cases of classifications based on conventional kinds. This section also leaves me a bit confused as whether it means that the authors reject any ontological approach to the past, which does not seem to be the case given the sentence p. 21 "In a way, a pluralistic approach using epistemic kinds might be interesting for Archaeology, especially if conceptualism is applied."

While the paper does present an interesting discussion of fundamentals in archaeological classification and the fact that the authors do present a convincing case for being explicit in our theoretical approaches to classifications, the paper could be improved by better integrating the existing literature on classification in archaeology, which, even if it has probably not received enough attention by archaeologists, is still very much present in some works.

As minor points, I have noted a few typos (others might be present) in the text:

- p. 7 "will be find"

- p. 9 "can be used accordingly to the subject"

- p. 14 "can be, in principle, look much simpler"