Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

20 Dec 2020

For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente.Marco Carpentieri, Marta Arzarello https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/2ptjbInvestigating the opportunistic debitage – an experimental approachRecommended by Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by David Hérisson and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper “For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente” [1] submitted by M. Carpentieri and M. Arzarello is a welcome addition to a growing number of studies focusing on flaking methods showing little to no core preparation, e.g., [2–4]. These flaking methods are often overlooked or seen as ‘simple’, which, in a Middle Palaeolithic context, sometimes leads to a dichotomy of Levallois vs. non-Levallois debitage (e.g., see discussion in [2]). The authors address this topic by first providing a definition for ‘opportunistic debitage’, derived from the definition of the ‘Alternating Surfaces Debitage System’ (SSDA, [5]). At the core of the definition is the adaptation to the characteristics (e.g., natural convexities and quality) of the raw material. This is one main challenge in studying this type of debitage in a consistent way, as the opportunistic debitage leads to a wide range of core and flake morphologies, which have sometimes been interpreted as resulting from different technical behaviours, but which the authors argue are part of a same ‘methodological substratum’ [1]. This article aims to further characterise the ‘opportunistic debitage’. The study relies on four archaeological assemblages from Italy, ranging from the Lower to the Upper Pleistocene, in which the opportunistic debitage has been recognised. Based on the characteristics associated with the occurrence of the opportunistic debitage in these assemblages, an experimental replication of the opportunistic debitage using the same raw materials found at these sites was conducted, with the aim to gain new insights into the method. Results show that experimental flakes and cores are comparable to the ones identified as resulting from the opportunistic debitage in the archaeological assemblage, and further highlight the high versatility of the opportunistic method. One outcome of the experimental replication is that a higher flake productivity is noted in the opportunistic centripetal debitage, along with the occurrence of 'predetermined-like' products (such as déjeté points). This brings the authors to formulate the hypothesis that the opportunistic debitage may have had a role in the process that will eventually lead to the development of Levallois and Discoid technologies. How this articulates with for example current discussions on the origins of Levallois technologies (e.g., [6–8]) is an interesting research avenue. This study also touches upon the question of how the implementation of one knapping method may be influenced by the broader technological knowledge of the knapper(s) (e.g., in a context where Levallois methods were common vs a context where they were not). It makes the case for a renewed attention in lithic studies for flaking methods usually considered as less behaviourally significant. [1] Carpentieri M, Arzarello M. 2020. For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente. OSF Preprints, doi:10.31219/osf.io/2ptjb [2] Bourguignon L, Delagnes A, Meignen L. 2005. Systèmes de production lithique, gestion des outillages et territoires au Paléolithique moyen : où se trouve la complexité ? Editions APDCA, Antibes, pp. 75–86. Available: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00447352 [3] Arzarello M, De Weyer L, Peretto C. 2016. The first European peopling and the Italian case: Peculiarities and “opportunism.” Quaternary International, 393: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.005 [4] Vaquero M, Romagnoli F. 2018. Searching for Lazy People: the Significance of Expedient Behavior in the Interpretation of Paleolithic Assemblages. J Archaeol Method Theory, 25: 334–367. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9339-x [5] Forestier H. 1993. Le Clactonien : mise en application d’une nouvelle méthode de débitage s’inscrivant dans la variabilité des systèmes de production lithique du Paléolithique ancien. Paléo, 5: 53–82. doi:10.3406/pal.1993.1104 [6] Moncel M-H, Ashton N, Arzarello M, Fontana F, Lamotte A, Scott B, et al. 2020. Early Levallois core technology between Marine Isotope Stage 12 and 9 in Western Europe. Journal of Human Evolution, 139: 102735. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102735 [7] White M, Ashton N, Scott B. 2010. The emergence, diversity and significance of the Mode 3 (prepared core) technologies. Elsevier. In: Ashton N, Lewis SG, Stringer CB, editors. The ancient human occupation of Britain. Elsevier. Amsterdam, pp. 53–66. [8] White M, Ashton N. 2003. Lower Palaeolithic Core Technology and the Origins of the Levallois Method in North‐Western Europe. Current Anthropology, 44: 598–609. doi:10.1086/377653 | For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente. | Marco Carpentieri, Marta Arzarello | <p>The opportunistic debitage, originally adapted from Forestier’s S.S.D.A. definition, is characterized by a strong adaptability to local raw material morphology and its physical characteristics and it is oriented towards flake production. Its mo... |  | Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic | Alice Leplongeon | 2020-07-23 14:26:04 | View | |

11 Dec 2023

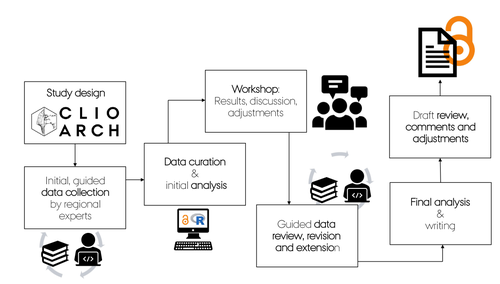

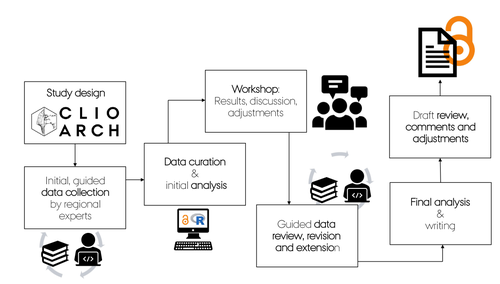

A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in EuropeFelix Riede, David N. Matzig, Miguel Biard, Philippe Crombé, Javier Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, Federica Fontana, Daniel Groß, Thomas Hess, Mathieu Langlais, Ludovic Mevel, William Mills, Martin Moník, Nicolas Naudinot, Caroline Posch, Tomas Rimkus, Damian Stefański, Hans Vandendriessche, Shumon T. Hussain https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8195587Questioning Final Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic cultural taxonomy with a data-driven statistical approachRecommended by Anaïs Vignoles based on reviews by Dirk Leder and 2 anonymous reviewersCultural taxonomies are an essential tool for archaeologists working with prehistoric material cultures as they have historically been used to create the basic analytical units for studying cultural evolution through time (de Mortillet, 1883 ; Breuil, 1913). This approach has its limits as the taxonomic units are essentially etic constructions, i.e., they are defined in a cultural context exterior to the one that produced the material culture on which they are based (e.g., Pesesse, 2019). But to approach questions related to cultural evolution, one has to define archaeological units with clear geographic and chronological delineations in order to be compared synchronically and diachronically (e.g., Willey and Philips, 1958). In « A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolitic/Earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe », F. Riede and colleagues propose a novel and interesting approach to question the end of the Palaeolithic and beginning of the Mesolithic’s « named archaeological cultures » (NACs) analytical pertinence (Riede et al., 2023). In this particular context, NACs are indeed very numerous (n = 86) and result from complex and regional research histories. It seems thus pertinent to question the extent to which the said NACs chronological and geographic patterns result from past cultural diversity and evolution, and are not artefacts of research. To do so, the authors adopted a data-driven approach that they describe in detail in the paper. First, they gathered an European data base of lithic tool-kit composition, blade and bladelet technology and armature morphology at 350 key sites considered representative of NACs, dated between 15 and 11 ka (Hussain et al., 2023). These data were then analyzed using geometric morphometrics and a set of statisticaal tests in order to 1) test the coherence of these taxonomic units, and 2) test the chronological change in artefact shape variation. The authors conclude that the data set is partially biased by reasearch practices and histories, as their data-driven approach has only partially replicated traditional NACs for the european Late Palaeolithic/Early Mesolithic. However, their analysis of armature shape evolution has shown a tendency to diversification overtime, a pattern that was already observed in more « traditional » approaches. This study is, in my opinion, an excellent contribution for a significant step in macro-regional approaches to the archaeological record: defining discrete archaeological units that serve as a basis for subsequent analyses aimed at delineating cultural evolutionary processes. The authors propose a carefully designed and statistically grounded procedure in order to achieve these definitions in the most replicable and explicit possible manner. Taking advantage of drawings as a primary source of information is also very original despite several limitations of this approach (such as the necessary selection of most typical artefacts to be represented, the incompleteness of data publication or the difficulty to access all published work across such a large geographic area). The results of the study are convincing enough to allow the authors to discuss the pertinence of European Late Paleo/Early Mesolithic NACs, the potential epistemological and historical factors that could affect this taxonomic framework, as well as to give more weight to the traditional hypothesis of lithic cultural diversification towards the end of the Pleistocene/beginning of the Holocene in Europe. I would also like to underline the authors’ important efforts to ensure transparence and replicability of their study, as well as the accessibility of the data, thanks to extensive supplementary data and a data paper describing their data set in detail. Anaïs L. Vignoles References Breuil, H. (1913). Les subdivisions du paléolithique supérieur et leur signification. In Congrès international d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques - compte-rendu de la XIVème session, tome 1:165‑238. Genève: Imprimerie Albert Kündig. Hussain, S. T., Riede, F., Matzig, D. N., Biard, M., Crombé, P., Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, J., Fontana, F., Groß, D., Hess, T., Langlais, M., Mevel, L., Mills, W., Moník, M., Naudinot, N., Posch, C., Rimkus, T., Stefański, D. and Vandendriessche, H. (2023). A Pan-European Dataset Revealing Variability in Lithic Technology, Toolkits, and Artefact Shapes ~15-11 Kya. Scientific Data 10 (1): 593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02500-9. Mortillet, G. (1883). Le Préhistorique, antiquité de l’homme. Reinwald. Paris. Pesesse, D. (2019). Analyser un silex, le façonner à nouveau ? Sur certains usages de la chaîne opératoire au Paléolithique supérieur. Techniques & culture, no 71: 74‑77. https://doi.org/10.4000/tc.11321. Riede, F., Matzig, D. N., Biard, M., Crombé, P., Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, J., Fontana, F., Groß, D., Hess, T., Langlais, M., Mevel, L., Mills, W., Moník, M., Naudinot, N., Posch, C., Rimkus, T., Stefański, D., Vandendriessche, H. and Hussain, S. T. (2023). A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe, Zenodo, 8195587., ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8195587 Willey, G. R. and Phillips, P. (1958). Method and Theory in American Archaeology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. | A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe | Felix Riede, David N. Matzig, Miguel Biard, Philippe Crombé, Javier Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, Federica Fontana, Daniel Groß, Thomas Hess, Mathieu Langlais, Ludovic Mevel, William Mills, Martin Moník, Nicolas Naudinot, Caroline Posch, Tomas Rimkus,... | <p>Archaeological systematics, together with spatial and chronological information, are commonly used to infer cultural evolutionary dynamics in the past. For the study of the Palaeolithic, and particularly the European Final Palaeolithic and earl... |  | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Mesolithic, Upper Palaeolithic | Anaïs Vignoles | 2023-07-29 16:06:17 | View | |

31 Jan 2024

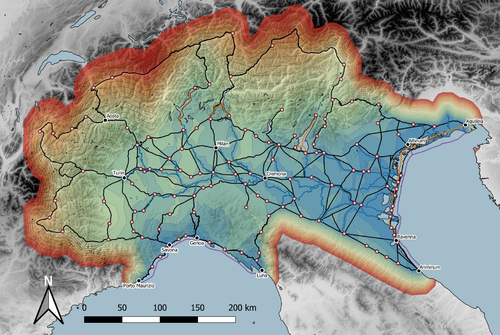

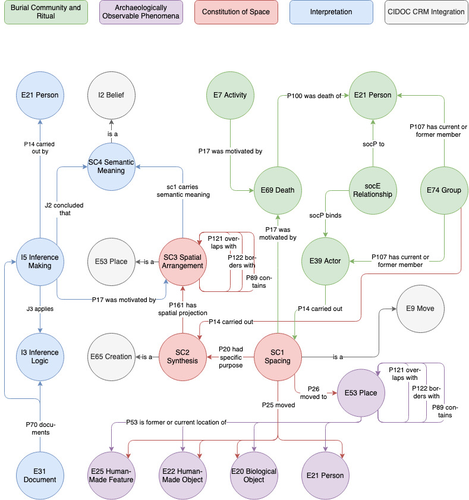

Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman periodJames Page https://zenodo.org/records/7971399Modelling Roman Transport Infrastructure in Northern ItalyRecommended by Andrew McLean based on reviews by Pau de Soto and Adam PažoutStudies of the economy of the Roman Empire have become increasingly interdisciplinary and nuanced in recent years, allowing the discipline to make great strides in data collection and importantly in the methods through which this increasing volume of data can be effectively and meaningfully analysed [see for example 1 and 2]. One of the key aspects of modelling the ancient economy is understanding movement and transport costs, and how these facilitated trade, communication and economic development. With archaeologists adopting more computational techniques and utilising GIS analysis beyond simply creating maps for simple visualisation, understanding and modelling the costs of traversing archaeological landscapes has become a much more fruitful avenue of research. Classical archaeologists are often slower to adopt these new computational techniques than others in the discipline. This is despite (or perhaps due to) the huge wealth of data available and the long period of time over which the Roman economy developed, thrived and evolved. This all means that the Roman Empire is a particularly useful proving ground for testing and perfecting new methodological developments, as well as being a particularly informative period of study for understanding ancient human behaviour more broadly. This paper by Page [3] then, is well placed and part of a much needed and growing trend of Roman archaeologists adopting these computational approaches in their research. Page’s methodology builds upon De Soto’s earlier modelling of transport costs [4] and applies it in a new setting. This reflects an important practice which should be more widely adopted in archaeology. That of using existing, well documented methodologies in new contexts to offer wider comparisons. This allows existing methodologies to be perfected and tested more robustly without reinventing the wheel. Page does all this well, and not only builds upon De Soto’s work, but does so using a case study that is particularly interesting with convincing and significant results. As Page highlights, Northern Italy is often thought of as relatively isolated in terms of economic exchange and transport, largely due to the distance from the sea and the barriers posed by the Alps and Apennines. However, in analysing this region, and not taking such presumptions for granted, Page quite convincingly shows that the waterways of the region played an important role in bringing down the cost of transport and allowed the region to be far more interconnected with the wider Roman world than previous studies have assumed. This article is clearly a valuable and important contribution to our understanding of computational methods in archaeology as well as the economy and transport network of the Roman Empire. The article utilises innovative techniques to model transport in an area of the Roman Empire that is often overlooked, with the economic isolation of the area taken for granted. Having high quality research such as this specifically analysing the region using the most current methodologies is of great importance. Furthermore, developing and improving methodologies like this allow for different regions and case studies to be analysed and directly compared, in a way that more traditional analyses simply cannot do. As such, Page has demonstrated the importance of reanalysing traditional assumptions using the new data and analyses now available to archaeologists. References [1] Brughmans, T. and Wilson, A. (eds.) (2022). Simulating Roman Economies: Theories, Methods, and Computational Models. Oxford. [2] Dodd, E.K. and Van Limbergen, D. (eds.) (2024). Methods in Ancient Wine Archaeology: Scientific Approaches in Roman Contexts. London ; New York. [3] Page, J. (2024). Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman period, Zenodo, 7971399, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7971399 [4] De Soto P (2019). Network Analysis to Model and Analyse Roman Transport and Mobility. In: Finding the Limits of the Limes. Modelling Demography, Economy and Transport on the Edge of the Roman Empire. Ed. by Verhagen P, Joyce J, and Groenhuijzen M. Springer Open Access, pp. 271–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04576-0_13 | Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman period | James Page | <p>Northern Italy has often been characterised as an isolated and marginal area during the Roman period, a region constricted by mountain ranges and its distance from major shipping lanes. Historians have frequently cited these obstacles, alongsid... |  | Classic, Computational archaeology | Andrew McLean | 2023-05-28 15:11:31 | View | |

17 Dec 2020

Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbolsGuillaume Porraz, John E. Parkington, Patrick Schmidt, Gérald Bereiziat, Jean-Philip Brugal, Laure Dayet, Marina Igreja, Christopher E. Miller, Viola C. Schmid, Chantal Tribolo, Aurore Val, Christine Verna, Pierre-Jean Texier https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/ch53rExperimentation as a driving force for innovation in the Pre-Still Bay from Southern AfricaRecommended by Anne Delagnes based on reviews by Francesco d'Errico, Enza Elena Spinapolice and Kathryn RanhornThe article submitted by Guillaume Porraz et al. [1] shed light on the evolutionary changes recorded during the Pre-Still Bay Lynn stratigraphic unit (SU) from Diepkloof (Southern Africa). It promotes a multi-proxy and integrative approach based on a set of innovative behaviors, such as the engraving of geometric forms, silcrete heat- treatment, the use of adhesive, bladelet and bifacial tools production. This approach is not so common in Middle Stone Age (MSA) studies and makes a lot of sense for discussing the mechanisms that have fostered later innovations during the Still Bay and Howiesons Poort periods. The various innovations that emerge synchronously in this layer contrast with earlier innovations which appear as isolated phenomena in the MSA archaeological record. The strong inventiveness documented in Lynn SU is reported to a phase of experimentation for testing new ideas, new behaviors that would have played a crucial role for the emergence of the Still Bay in a context of socio-economic transformation. The data presented in this article broadens the scope of two previous articles [2-3] based on a more representative record, collected on an area of 3,5 m² opposed to 2 m² previously, and on the first presentation and description of an engraved bone with a rhomboid pattern. Macro- and microscopic analyses together with the analysis of the distribution of the engraved lines argue convincingly for an intentional engraving. This article constitutes a key contribution to the question of HOW emerged modern cultures in Southern Africa, while calling for further research related to sites’ function, environment and local resources to address the ever-debated question of WHY the MSA groups from Southern Africa developed such unprecedented inventiveness. It makes no doubt that this article deserves recommendation by PCI Archaeology. [1] Porraz, G., Schmidt, P., Bereiziat, G., Brugal, J.Ph., Dayet, L., Igreja, M., Miller, C.E., Viola, C., Tribolo, C., Val, A., Verna, C., Texier, P.J. 2020. Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbols. 10.32942/osf.io/ch53r [2] Porraz, G., Texier, P.J., Archer, W., Piboule, M., Rigaud, J.P, Tribolo, C. 2013. Technological successions in the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science 40, 3376–3400. 10.1016/j.jas.2013.02.012 [3] Porraz, G., Texier, J.P. Miller, C.E., 2014. Le complexe bifacial Still Bay et ses modalités d’émergence à l’abri Diepkloof (Middle Stone Age, Afrique du Sud). In: XXVIIème Congrès Préhistorique de France, Transitions, Ruptures et Continuité en Préhistoire. Mémoires de la Société Préhistorique Française, 155–175. | Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbols | Guillaume Porraz, John E. Parkington, Patrick Schmidt, Gérald Bereiziat, Jean-Philip Brugal, Laure Dayet, Marina Igreja, Christopher E. Miller, Viola C. Schmid, Chantal Tribolo, Aurore Val, Christine Verna, Pierre-Jean Texier | <p>In South Africa, key technologies and symbolic behaviors develop as early as the later Middle Stone Age in MIS5. These innovations arise independently in various places, contexts and forms, until their full expression during the Still Bay and t... |  | Africa, Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic, Symbolic behaviours | Anne Delagnes | 2020-08-04 09:13:27 | View | |

26 Apr 2022

Archaeophenomics of ancient domestic plants and animals using geometric morphometrics : a reviewAllowen Evin, Laurent Bouby, Vincent Bonhomme, Angèle Jeanty, Marine Jeanjean, Jean-Frédéric Terral https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/skeu5Archaeophenomics: an up-and-coming field in bioarchaeologyRecommended by Anneke H. van Heteren based on reviews by Stefan Schlager and 1 anonymous reviewerAnneke H. van Heteren based on reviews by Stefan Schlager and 1 anonymous reviewer Phenomics is the analysis of high-dimensional phenotypic data [1]. Phenomics research strategies are capable of linking genetic variation to phenotypic variation [2], but a genetic component is not absolutely necessary. The paper “Archaeophenomics of ancient domestic plants and animals using geometric morphometrics: a review” by Evin and colleagues [3] examines the use of geometric morphometrics in bioarchaeology and coins the term archaeophenomics. Archaeophenomics can be described as the large-scale phenotyping of ancient remains, and both addresses taxonomic identification, as well as infers spatio-temporal agrobiodiversity dynamics. It is a relatively new field in bioarchaeology with the first paper using this approach stemming from 2004. This study by Evin et al. [3] presents an excellent review and unquestionably demonstrates the potential of archaeophenomics. The authors provide an exhaustive review specifically of bioarchaeological studies in international journals using geometric morphometrics to study archaeological remains of domestic species. Although geometric morphometrics lends itself well for archaeophenomics, readers should keep in mind that this is not the only method and other approaches might equally fall under archaeophenomics as long as high-dimensional phenotypic archaeological data are involved. Distinguishing archaeophenomics from phenomics is important because of a critical difference. Archaeological remains are often altered by taphonomical processes. As such data may not be as complete as when working with modern specimens. Although this poses difficulties, morphometric analyses can usually still be performed as long as the structures presenting the relevant geometrical features are present. Even fragmented remains can be studied with a restricted version of the original landmarking/measurement protocol. Evin et al. [3] define archaeophenomics as “phenomics of the past”. This is only partly correct. It can be deduced from their review that they really mean phenomics of our (human) past. This leaves a gap for phenomics of the non-human past, for which I suggest the term palaeophenomics. [1] Jin, L. (2021). Welcome to the Phenomics Journal. Phenomics, 1, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43657-020-00009-4.

| Archaeophenomics of ancient domestic plants and animals using geometric morphometrics : a review | Allowen Evin, Laurent Bouby, Vincent Bonhomme, Angèle Jeanty, Marine Jeanjean, Jean-Frédéric Terral | <p>Geometric morphometrics revolutionized domestication studies through the precise quantification of the phenotype of ancient plant and animal remains. Geometric morphometrics allow for an increasingly detailed understanding of the past agrobiodi... |  | Archaeobotany, Archaeometry, Bioarchaeology, Zooarchaeology | Anneke H. van Heteren | 2022-02-17 09:50:39 | View | |

08 Apr 2024

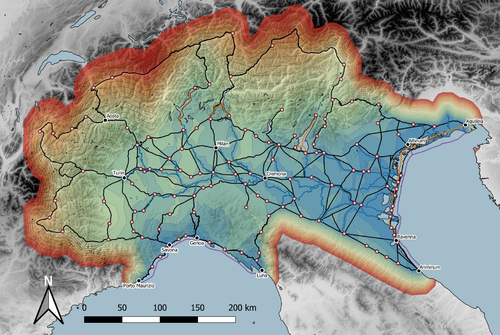

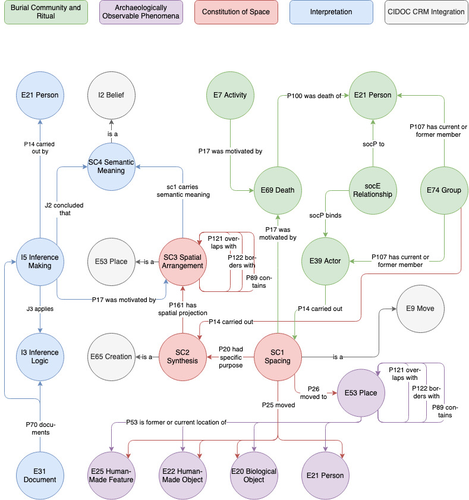

Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contextsAline Deicke https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8310170A new approach to a data ontology for the qualitative assessment of funerary spacesRecommended by Asuman Lätzer-Lasar based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The paper by Aline Deicke [1] is very readable, and it succeeds in presenting a still unnoticed topic in a well-structured way. It addresses the topic of “how to model social-spatial relations in antiquity”, as the title concisely implies, and makes important and interesting points about their interrelationship by drawing on latest theories of sociologists such as Martina Löw combined with digital tools, such as the CIDOC CRM-modeling. The author provides an introductory insight into the research history of funerary archaeology and addresses the problematic issue of not having investigated fully the placement of entities of the grave inventory. So far, the focus of the analysis has been on the composition of the assemblage and not on the positioning within this space-and time-limited context. However, the positioning of the various entities within the burial context also reveals information about the objects themselves, their value and function, as well as about the world view and intentions of the living and dead people involved in the burial. To obtain this form of qualitative data, the author suggests modeling knowledge networks using the CIDOC CRM. The method allows to integrate the spatial turn combined with aspects of the actor-network-theory. The theoretical backbone of the contribution is the fundamental scholarship of Martina Löw’s “Raumsoziologie” (sociology of space), especially two categories of action namely placing and spacing (SC1). The distinction between the two types of action enables an interpretative process that aims for the detection of meaningfulness behind the creation process (deposition process) and the establishment of spatial arrangement (find context). To illustrate with a case study, the author discusses elite burial sites from the Late Urnfield Period covering a region north of the Alps that stretches from the East of France to the entrance of the Carpathian Basin. With the integration of very basic spatial relations, such as “next to”, “above”, “under” and qualitative differentiations, for instance between iron and bronze knives, the author detects specific patterns of relations: bronze knives for food preparing (ritual activities at the burial site), iron knives associated with the body (personal accoutrement). The complexity of the knowledge engineering requires the gathering of several CIDOC CRM extensions, such as CRMgeo, CRMarchaeo, CRMba, CRMinf and finally CRMsoc, the author rightfully suggests. In the end, the author outlines a path that can be used to create this kind of data model as the basis for a graph database, which then enables a further analysis of relationships between the entities in a next step. Since this is only a preliminary outlook, no corrections or alterations are needed. The article is an important step in advancing digital archaeology for qualitative research. References [1] Deicke, A. (2024). Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contexts. Zenodo, 8310170, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8310170 | Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contexts | Aline Deicke | <p>Burials have long been one of the most important sources of archaeology, especially when studying past social practices and structure. Unlike archaeological finds from settlements, objects from graves can be assumed to have been placed there fo... |  | Computational archaeology, Protohistory, Spatial analysis, Theoretical archaeology | Asuman Lätzer-Lasar | 2023-09-01 23:15:41 | View | |

14 Sep 2020

A way to break bones? The weight of intuitivenessDelphine Vettese, Trajanka Stavrova, Antony Borel, Juan Marin, Marie-Hélène Moncel, Marta Arzarello, Camille Daujeard https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/rebwtBreaking bones: Nature or Culture?Recommended by Beatrice Demarchi and Reuven Yeshurun based on reviews by Terry O'Connor, Alan Outram and 1 anonymous reviewerThe nature of breaking long bones for obtaining marrow is important in Paleolithic archaeology, due to its widespread, almost universal, character. Provided that hammer-stone percussion marks can be correctly identified using experimental datasets (e.g., [1]), the anatomical location and count of the marks may be taken to reflect recurrent “cultural” traditions in the Paleolithic [2]. Were MP humans breaking bones intuitively or did they abide by a strict “protocol”, and, if the latter, was this protocol optimized for marrow retrieval or geared towards another, less obvious goal? This paper provides a baseline for location analyses of percussion marks. Their dataset may therefore be regarded as a null hypothesis according to which the archaeological data could be tested. If Paleolithic patterns of percussion marks differ from Vettese et al.’s [3] “intuitive” patterns, then the null hypothesis is disproved and one can argue in favor of a learned pattern. The latter can be a result of ”culture”, as Vettese et al. [3] phrase it, in the sense of nonrandom action that draws on transmitted knowledge. Such comparisons bear a great potential for understanding the degree of technological behavior in the Paleolithic by factoring out the “natural” constraints of bone breakage patterns. Vettese et al. [3: fig. 14] started this discourse by comparing their experimental dataset to some Middle and Upper Paleolithic faunas; we are confident that many other studies will follow. Bibliography [1]Pickering, T.R., Egeland, C.P., 2006. Experimental patterns of hammerstone percussion damage on bones: Implications for inferences of carcass processing by humans. J. Archaeol. Sci. 33, 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.09.001 [2]Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Domínguez-Rodrigo, M., Lozano, S., Pastó, I., Riba, D., Vaquero, M., Peris, J.F., Arsuaga, J.L., de Castro, J.M.B., Carbonell, E., 2013. Learning by Heart: Cultural Patterns in the Faunal Processing Sequence during the Middle Pleistocene. PLoS One 8, e55863. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055863 [3]Vettese, D., Stavrova, T., Borel, A., Marin, J., Moncel, M.-H., Arzarello, M., Daujeard, C. (2020) A way to break bones? The weight of intuitiveness. BioRxiv, 011320, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.31.011320 | A way to break bones? The weight of intuitiveness | Delphine Vettese, Trajanka Stavrova, Antony Borel, Juan Marin, Marie-Hélène Moncel, Marta Arzarello, Camille Daujeard | <p>During the Middle Paleolithic period, bone marrow extraction was an essential source of fat nutrients for hunter-gatherers especially throughout cold and dry seasons. This is attested by the recurrent findings of percussion marks in osteologica... |  | Archaeometry, Bioarchaeology, Spatial analysis, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Beatrice Demarchi | 2020-04-01 11:52:05 | View | |

30 Sep 2022

Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF dataBharath Nair, Ismael Rodríguez Palomo, Bo Markussen, Carsten Wiuf, Sarah Fiddyment and Matthew Collins https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.13.483627Assessing glutamine deamination in ancient parchment samplesRecommended by Beatrice Demarchi based on reviews by Maria Codlin and 3 anonymous reviewersData authenticity and approaches to data authentication are crucial issues in ancient protein research. The advent of modern mass spectrometry has enabled the detection of traces of ancient biomolecules contained in fossils, including protein sequences. However, detecting proteins in ancient samples does not equate to demonstrating their endogenous nature: instead, if the mechanisms that drive protein preservation and degradation are understood, then the extent of protein diagenesis can be used for evaluating preservational quality, which in turn may be related to the authenticity of the protein data. The post-mortem deamidation of asparaginyl and glutamyl residues is a key degradation reaction, which can be assessed effectively on the basis of mass spectrometry data, and which has accrued a long history of research, both in terms of describing the mechanisms governing the reactions and with regard to the best strategies for assessing and quantifying the extent of glutamine (Gln) and asparagine (Asn) deamidation in ancient samples (Pal Chowdhury et al., 2019; Ramsøe et al., 2021, 2020; Schroeter and Cleland, 2016; Simpson et al., 2016; Solazzo et al., 2014; Welker et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2012). In their paper, Nair and colleagues (2022) build on this wealth of knowledge and present a tool for quantifying the extent of Gln deamidation in parchment. Parchment is a collagen-based material which can yield extraordinary insights into manuscript manufacturing practices in the past, as well as on the daily lives of the people who assembled and used them (“biocodicology”) (Fiddyment et al., 2021, 2019, 2015; Teasdale et al., 2017). Importantly, the extent of deamidation can be directly related to the quality of the parchment produced: rapid direct deamidation of Gln is induced by the liming process, therefore high extents of deamidation are linked to prolonged exposure to the high pH conditions which are typical of liming, thus implying lower-quality parchment. Nair et al.’s approach focuses on collagen peptides which are typically detected during MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analyses of parchment and build a simple three-step workflow able to yield an overall index of deamidation for a sample (the parchment glutamine index - PQI) 一 taking into account that different Gln residues degrade at different rates according to their micro-chemical environment. The first step involves pre-processing the MALDI spectra, since Nair et al. are specifically interested in maximising information which can be obtained by low-quality data. The second step builds on well-established methods for quantifying Q → E from MALDI-TOF data by modelling the convoluted isotope distributions (Wilson et al., 2012). Once relative rates of deamidation in selected peptides within a given sample are calculated, the third step uses a mixed effects model to combine the individual deamidation estimates and to obtain an overall estimate of the deamidation for a parchment sample (PQI). The PQI can be used effectively for assessing parchment quality, as the authors show for the dataset from Orval Abbey. However, PQI could also have wider applications to the study of processed collagen, which is widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries. In general, the study by Nair et al. is a welcome addition to a growing body of research on protein diagenesis, which will ultimately improve models for the assessment of the authenticity of biomolecular data in archaeology. References Chowdhury, P.M., Wogelius, R., Manning, P.L., Metz, L., Slimak, L., and Buckley, M. 2019. Collagen deamidation in archaeological bone as an assessment for relative decay rates. Archaeometry 61:1382–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12492 Fiddyment, S., Goodison, N.J., Brenner, E., Signorello, S., Price, K., and Collins, M.J.. 2021. Girding the loins? Direct evidence of the use of a medieval parchment birthing girdle from biomolecular analysis. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.202055 Fiddyment,S., Holsinger, B., Ruzzier, C., Devine, A., Binois, A., Albarella, U., Fischer, R., Nichols, E., Curtis, A., Cheese, E., Teasdale, M.D., Checkley-Scott, C., Milner, S.J., Rudy, K.M., Johnson, E.J., Vnouček, J., Garrison, M., McGrory, S., Bradley, D.G., and Collins, M.J. 2015. Animal origin of 13th-century uterine vellum revealed using noninvasive peptide fingerprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:15066–15071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1512264112 Fiddyment, S., Teasdale, M.D., Vnouček, J., Lévêque, É., Binois, A., and Collins, M.J. 2019. So you want to do biocodicology? A field guide to the biological analysis of parchment. Heritage Science 7:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0278-6 Nair, B., Rodríguez Palomo, I., Markussen, B., Wiuf, C., Fiddyment, S., and Collins, M. Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF data. BiorRxiv, 2022.03.13.483627, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.13.483627 Ramsøe, A., Crispin, M., Mackie, M., McGrath, K., Fischer, R., Demarchi, B., Collins, M.J., Hendy, J., and Speller, C. 2021. Assessing the degradation of ancient milk proteins through site-specific deamidation patterns. Sci Rep 11:7795. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87125-x Ramsøe, A., van Heekeren, V., Ponce, P., Fischer, R., Barnes, I., Speller, C., and Collins, M.J. 2020. DeamiDATE 1.0: Site-specific deamidation as a tool to assess authenticity of members of ancient proteomes. J Archaeol Sci 115:105080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2020.105080 Schroeter, E.R., and Cleland, T.P. 2016. Glutamine deamidation: an indicator of antiquity, or preservational quality? Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 30:251–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7445 Simpson, J.P., Penkman, K.E.H., and Demarchi, B. 2016. The effects of demineralisation and sampling point variability on the measurement of glutamine deamidation in type I collagen extracted from bone. J Archaeol Sci 69: 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.002 Solazzo, C., Wilson, J., Dyer, J.M., Clerens, S., Plowman, J.E., von Holstein, I., Walton Rogers, P., Peacock, E.E., and Collins, M.J. 2014. Modeling deamidation in sheep α-keratin peptides and application to archeological wool textiles. Anal Chem 86:567–575. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac4026362 Teasdale, M.D., Fiddyment, S., Vnouček, J., Mattiangeli, V., Speller, C., Binois, A., Carver, M., Dand, C., Newfield, T.P., Webb, C.C., Bradley, D.G., and Collins M.J. 2017. The York Gospels: a 1000-year biological palimpsest. R Soc Open Sci 4:170988. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.170988 Welker, F., Soressi, M.A., Roussel, M., van Riemsdijk, I., Hublin, J.-J., and Collins, M.J. 2016. Variations in glutamine deamidation for a Châtelperronian bone assemblage as measured by peptide mass fingerprinting of collagen. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 3:15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2016.1258825 Wilson, J., van Doorn, N.L., and Collins, M.J. 2012. Assessing the extent of bone degradation using glutamine deamidation in collagen. Anal Chem 84:9041–9048. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac301333t | Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF data | Bharath Nair, Ismael Rodríguez Palomo, Bo Markussen, Carsten Wiuf, Sarah Fiddyment and Matthew Collins | <p style="text-align: justify;">Parchment was used as a writing material in the Middle Ages and was made using animal skins by liming them with Ca(OH)<span class="math-tex">\( _2 \)</span>. During liming, collagen peptides containing Glutamine (Q)... | Bioarchaeology, Europe, Medieval, Zooarchaeology | Beatrice Demarchi | 2022-03-22 12:54:10 | View | ||

26 Sep 2022

The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspectiveSolange Rigaud, John O’Hara, Laurent Charles, Elena Man-Estier, Patrick Paillet https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/z7pqgCaching up with the study of the procurement of symbolic raw materials in the Upper PalaeolithicRecommended by Beatrice Demarchi based on reviews by Begoña Soler Mayor , Catherine Dupont and Lawrence StrausThe manuscript "The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective" by Solange Rigaud and colleagues (Rigaud et al. 2022) is a perfect demonstration that appropriate scientific methodologies can be used effectively in order to enhance the historical value of findings from “old” collections, despite the lack of secure stratigraphic and contextual data. The shell assemblage (n = 377) investigated here (from Rochereil, Dordogne) had been excavated during the first half of the 20th century (Jude 1960) and reported in 1993 (Taborin 1993), but only this recent analysis revealed that it was composed of largely unmodified mollusc shells, most of allochthonous origin. Rigaud et al. interpret this finding as the raw materials used to produce personal ornaments. This is especially significant, because the focus of research has been on the manufacture, use and exchange of personal ornaments in prehistory, much less so on the procurement of the raw materials. As such, the manuscript adds substantially to the growing literature on Magdalenian social networks. The authors carried out detailed taxonomic analysis based on morphological and morphometric characteristics and identified at least nine different species, including Dentalium sp., Ocenebra erinaceus, Tritia reticulata and T. gibbosula, as well as some bivalve specimens (Mytilus, Glycymeris, Spondylus, Pecten). Most of the species are commonly found in personal ornament assemblages from the Magdalenian, reflecting intentional selection (also shown by the size sorting of some of the taxa), and cultural continuity. However, microscopic examinations revealed securely-identified anthropogenic modifications on a very limited number of specimens: one Glycymeris valve (used as an ochre container), one Cardiidae valve (presence of a groove), one perforated Tritia gibbosula and two perforated Tritia reticulata bearing striations. The authors interpret this combination of anthropogenic vs natural “signals” as signifying that the assemblage represents raw material selected and stored for further processing. Assessing the provenance and age of the shells is therefore paramount: the shells found at Rochereil belong to species that can be found on both the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. Assuming that molluscan taxa distribution in the past is comparable to that for the present day, this implies the exploitation of two catchment areas and long-distance transportation to the site: taking sea-level changes into account, during the Magdalenian the Mediterranean used to lie at a distance of 350 km from Rochereil, and the Atlantic was not significantly closer (~200 km). Importantly, exploitation of fossil shells cannot be discounted on the basis of the data presented here; direct dating of some of the specimens (e.g. by radiocarbon, or amino acid racemisation geochronology) would be beneficial to clarify this issue and in general to improve chronological control on the accumulation of shells. Nonetheless, the authors argue that the closest fossil deposits also lie more than 200 km away from the site, thus the material is allochthonous in origin. In synthesis, the Rochereil assemblage represents an important step towards a better understanding of the procurement chain and of the production of ornaments during the European Upper Palaeolithic. References Jude, P. E. (1960). La grotte de Rocherreil: station magdalénienne et azilienne, Masson. Rigaud, S., O'Hara, J., Charles, L., Man-Estier, E. and Paillet, P. (2022) The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective. SocArXiv, z7pqg, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/z7pqg Taborin, Y. (1993). La parure en coquillage au Paléolithique, CNRS éditions. | The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective | Solange Rigaud, John O’Hara, Laurent Charles, Elena Man-Estier, Patrick Paillet | <p>Personal ornaments manufactured on marine and fossil shell are a significant element of Upper Palaeolithic symbolic material culture, and are often found at considerable distances from Pleistocene coastlines or relevant fossil deposits. Here, w... |  | Europe, Symbolic behaviours, Upper Palaeolithic | Beatrice Demarchi | 2022-04-23 19:20:02 | View | |

28 Feb 2021

A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic AgeAlain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/7dq3b/Open data on beads, pendants, blanks from the Ceramic Age CaribbeanRecommended by Ben Marwick based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang

The paper 'A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age' by Queffelec et al. [1] presents a description of a dataset of nearly 5000 lapidary artefacts from over 100 sites. The data are dominated by beads and pendants, which are mostly made from Diorite, Turquoise, Carnelian, Amethyst, and Serpentine. The raw material data is especially valuable as many of these are not locally available on the island. This holds great potential for exchange network analysis. The data may be especially useful for investigating one of the fundamental questions of this region: whether the Cedrosan and Huecan are separate, little related developments, with different origins, or variants or a single tradition [2]. In addition to metric and technological details about the artefacts, the data include a variety of locational details, including coordinates, distance to coast, and altitude. This enables many opportunities for future spatial analysis and geostatistical modelling to understand human behaviours relating to ornament production, use, and discard. I recommend the authors make a minor revision to Table 1 (spatial coverage of the dataset) to make the column with the citations conform to the same citation style used in the rest of the text. I warmly commend the authors for making transparency and reproducibility a priority when preparing their manuscript. Their use of the R Markdown format for writing reproducible, dynamic documents [3] is highly impressive. This is an excellent example for others in the international archaeological science community to follow. The paper is especially useful for researchers who are new to R and R Markdown because of the elegant and accessible way the authors document their research here. [1] Queffelec, A., Fouéré, P. and Caverne, J.-B. 2021. A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age. SocArXiv, 7dq3b, ver. 4 Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/7dq3b [2] Reed, J. A. and Petersen, J. B. 2001. A comparison of Huecan and Cedrosan Saladoid ceramics at the Trants site, Montserrat. In Proceedings of the XVIIIth International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology (pp. 253-267). [3] Marwick, B. 2017. Computational Reproducibility in Archaeological Research: Basic Principles and a Case Study of Their Implementation. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24, 424–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-015-9272-9 | A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age | Alain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne | <p>Lapidary artifacts show an impressive abundance and diversity during the Ceramic period in the Caribbean islands, especially at the beginning of this period. Most of the raw materials used in this production do not exist naturally on the island... |  | Neolithic, North America, Raw materials, South America, Spatial analysis, Symbolic behaviours | Ben Marwick | 2020-11-13 23:52:34 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer