Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

01 Sep 2023

Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854))Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552A zooarchaeological perspective on testudine bones from Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Southeast AsiaRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta

The study of the evolution of the human diet has been a central theme in numerous archaeological and paleoanthropological investigations. By reconstructing diets, researchers gain deeper insights into how humans adapted to their environments. The analysis of animal bones plays a crucial role in extracting dietary information. Most studies involving ancient diets rely heavily on zooarchaeological examinations, which, due to their extensive history, have amassed a wealth of data. During the Pleistocene–Holocene periods, testudine bones have been commonly found in a multitude of sites. The use of turtles and tortoises as food sources appears to stretch back to the Early Pleistocene [1-4]. More importantly, these small animals play a more significant role within a broader debate. The exploitation of tortoises in the Mediterranean Basin has been examined through the lens of optimal foraging theory and diet breadth models (e.g. [5-10]). According to the diet breadth model, resources are incorporated into diets based on their ranking and influenced by factors such as net return, which in turn depends on caloric value and search/handling costs [11]. Within these theoretical frameworks, tortoises hold a significant position. Their small size and sluggish movement require minimal effort and relatively simple technology for procurement and processing. This aligns with optimal foraging models in which the low handling costs of slow-moving prey compensate for their small size [5-6,9]. Tortoises also offer distinct advantages. They can be easily transported and kept alive, thereby maintaining freshness for deferred consumption [12-14]. For example, historical accounts suggest that Mexican traders recognised tortoises as portable and storable sources of protein and water [15]. Furthermore, tortoises provide non-edible resources, such as shells, which can serve as containers. This possibility has been discussed in the context of Kebara Cave [16] and noted in ethnographic and historical records (e.g. [12]). However, despite these advantages, their slow growth rate might have rendered intensive long-term predation unsustainable. While tortoises are well-documented in the Southeast Asian archaeological record, zooarchaeological analyses in this region have been limited, particularly concerning prehistoric hunter-gatherer populations that may have relied extensively on inland chelonian taxa. With the present paper Bochaton et al. [17] aim to bridge this gap by conducting an exhaustive zooarchaeological analysis of turtle bone specimens from four Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Thailand and Cambodia. These assemblages span from the Late Pleistocene to the first half of the Holocene. The authors focus on bones attributed to the yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata), which is the most prevalent taxon in the assemblages. The research include osteometric equations to estimate carapace size and explore population structures across various sites. The objective is to uncover human tortoise exploitation strategies in the region, and the results reveal consistent subsistence behaviours across diverse locations, even amidst varying environmental conditions. These final proposals suggest the possibility of cultural similarities across different periods and regions in continental Southeast Asia. In summary, this paper [17] represents a significant advancement in the realm of zooarchaeological investigations of small prey within prehistoric communities in the region. While certain approaches and issues may require further refinement, they serve as a comprehensive and commendable foundation for assessing human hunting adaptations.

References [1] Hartman, G., 2004. Long-term continuity of a freshwater turtle (Mauremys caspica rivulata) population in the northern Jordan Valley and its paleoenvironmental implications. In: Goren-Inbar, N., Speth, J.D. (Eds.), Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 61-74. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dtct.11 [2] Alperson-Afil, N., Sharon, G., Kislev, M., Melamed, Y., Zohar, I., Ashkenazi, R., Biton, R., Werker, E., Hartman, G., Feibel, C., Goren-Inbar, N., 2009. Spatial organization of hominin activities at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. Science 326, 1677-1680. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180695 [3] Archer, W., Braun, D.R., Harris, J.W., McCoy, J.T., Richmond, B.G., 2014. Early Pleistocene aquatic resource use in the Turkana Basin. J. Hum. Evol. 77, 74-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.02.012 [4] Blasco, R., Blain, H.A., Rosell, J., Carlos, D.J., Huguet, R., Rodríguez, J., Arsuaga, J.L., Bermúdez de Castro, J.M., Carbonell, E., 2011. Earliest evidence for human consumption of tortoises in the European Early Pleistocene from Sima del Elefante, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain. J. Hum. Evol. 11, 265-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.06.002 [5] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N., Surovell, T.A., Tchernov, E., Bar-Yosef, O., 1999. Palaeolithic growth pulses evidenced by small animal exploitation. Science 283, 190-194. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5399.190 [6] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., Surovell, T.A., 2000. The tortoise and the hare: small-game use, the Broad-Spectrum Revolution, and paleolithic demography. Curr. Anthropol. 41, 39-73. https://doi.org/10.1086/300102 [7] Stiner, M.C., 2001. Thirty years on the “Broad Spectrum Revolution” and paleolithic demography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 (13), 6993-6996. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.121176198 [8] Stiner, M.C., 2005. The Faunas of Hayonim Cave (Israel): a 200,000-Year Record of Paleolithic Diet. Demography and Society. American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 48. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge. [9] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., 2002. Approaches to prehistoric diet breadth, demography, and prey ranking systems in time and space. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 9, 181-214. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016530308865 [10] Blasco, R., Cochard, D., Colonese, A.C., Laroulandie, V., Meier, J., Morin, E., Rufà, A., Tassoni, L., Thompson, J.C. 2022. Small animal use by Neanderthals. In Romagnoli, F., Rivals, F., Benazzi, S. (eds.), Updating Neanderthals: Understanding Behavioral Complexity in the Late Middle Palaeolithic. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 123-143. ISBN 978-0-12-821428-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2019-0-03240-2 [11] Winterhalder, B., Smith, E.A., 2000. Analyzing adaptive strategies: human behavioural ecology at twenty-five. Evol. Anthropol. 9, 51-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(2000)9:2%3C51::aid-evan1%3E3.0.co;2-7 [12] Schneider, J.S., Everson, G.D., 1989. The Desert Tortoise (Xerobates agassizii) in the Prehistory of the Southwestern Great Basin and Adjacent areas. J. Calif. Gt. Basin Anthropol. 11, 175-202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825383 [13] Thompson, J.C., Henshilwood, C.S., 2014b. Nutritional values of tortoises relative to ungulates from the Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa: implications for foraging and social behaviour. J. Hum. Evol. 67, 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.010 [14] Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Smith, K.T., Maul, L.Ch., Sañudo, P., Barkai, R., Gopher, A. 2016. Tortoises as a Dietary Supplement: a view from the Middle Pleistocene site of Qesem Cave, Israel. Quat Sci Rev 133, 165-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.12.006 [15] Pepper, C., 1963. The truth about the tortoise. Desert Mag. 26, 10-11. [16] Speth, J.D., Tchernov, E., 2002. Middle Paleolithic tortoise use at Kebara Cave (Israel). J. Archaeol. Sci. 29, 471-483. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2001.0740 [17] Bochaton, C., Chantasri, S., Maneechote, M., Claude, J., Griggo, C., Naksri, W., Forestier, H., Sophady, H., Auertrakulvit, P., Bowonsachoti, J. and Zeitoun, V. (2023) Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed Tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854)), BioRXiv, 2023.04.27.538552 , ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552v3 | Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (*Indotestudo elongata* (Blyth, 1854)) | Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun | <p style="text-align: justify;">While non-marine turtles are almost ubiquitous in the archaeological record of Southeast Asia, their zooarchaeological examination has been inadequately pursued within this tropical region. This gap in research hind... |  | Asia, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Iratxe Boneta, Noel Amano | 2023-05-02 09:30:50 | View |

02 Mar 2024

A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasetsNimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733A new approach to Predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer

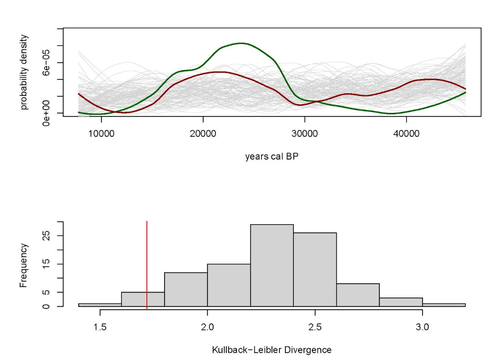

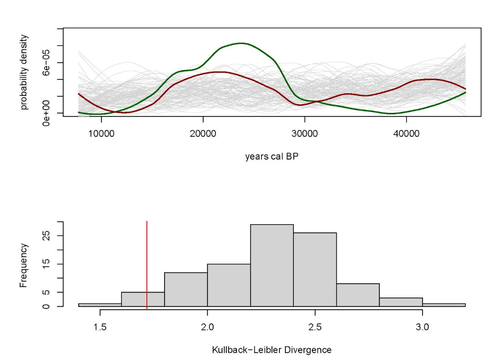

Various biological systems have been subjected to mathematical modelling to enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions among different species. Among these models, the predator-prey model holds a significant position. Its relevance stems not only from its application in biology, where it largely governs the coexistence of diverse species in open ecosystems, but also from its utility in other domains. Predator-prey dynamics have long been a focal point in population ecology, yet access to real-world data is confined to relatively brief periods, typically less than a century. Studying predator-prey dynamics over extended periods presents challenges due to the limited availability of population data spanning more than a century. The most extensive dataset is the hare-lynx records from the Hudson Bay Company, documenting a century of fur trade [1]. However, other records are considerably shorter, usually spanning decades [2,3]. This constraint hampers our capacity to investigate predator-prey interactions over centennial or millennial scales. Marom and Wolkowski [4] propose here that leveraging regional radiocarbon databases offers a solution to this challenge, enabling the reconstruction of predator-prey population dynamics over extensive timeframes. To substantiate this proposition, they draw upon examples from Pleistocene Beringia and the Holocene Judean Desert. This approach is highly relevant and might provide insight into ecological processes occurring at a time scale beyond the limits of current ecological datasets. The methodological approach employed in this article proposes that the summed probability distribution (SPD) of predator radiocarbon dates, which reflects changes in population size, will demonstrate either more or less variation than anticipated from random sampling in a homogeneous distribution spanning the same timeframe. A deviation from randomness would imply a covariation between predator and prey populations. This basic hypothesis makes no assumptions about the frequency, mechanism, or cause of predator-prey interactions, as it is assumed that such aspects cannot be adequately tested with the available data. If validated, this hypothesis would offer initial support for the idea that long-term regional radiocarbon data contain signals of predator-prey interactions. This approach could justify the construction of larger datasets to facilitate a more comprehensive exploration of these signal structures.

References [1] Elton, C. and Nicholson, M., 1942. The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada. J. Anim. Ecol. 11, 215–244. [2] Gilg, O., Sittler, B. and Hanski, I., 2009. Climate change and cyclic predator-prey population dynamics in the high Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01927.x [3] Vucetich, J.A., Hebblewhite, M., Smith, D.W. and Peterson, R.O., 2011. Predicting prey population dynamics from kill rate, predation rate and predator-prey ratios in three wolf-ungulate systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01855.x [4] Marom, N. and Wolkowski, U. (2024). A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets, BioRxiv, 566733, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733 | A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets | Nimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski | <p>Predator-prey interactions have been a central theme in population ecology for the past century, but real-world data sets only exist for recent, relatively short (<100 years) time spans. This limits our ability to study centennial/millennial... |  | Bioarchaeology, Environmental archaeology, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | 2023-12-12 14:37:22 | View | |

29 Aug 2023

Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious GamesTsaknaki, Electra; Anastasovitis, Eleftherios; Georgiou, Georgia; Alagialoglou, Kleopatra; Mavrokostidou, Maria; Kartsiakli, Vasiliki; Aidonis, Asterios; Protopsalti, Tania; Nikolopoulos, Spiros; Kompatsiaris, Ioannis https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981323AR and VR Gamification as a proof-of-conceptRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Sophie C. Schmidt and Tine Rassalle based on reviews by Sophie C. Schmidt and Tine Rassalle

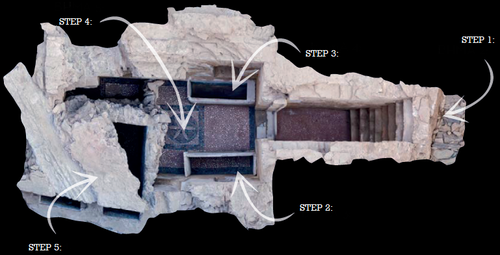

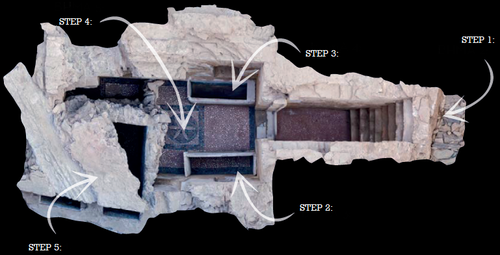

Tsaknaki et al. (2023) discuss a work-in-progress project in which the presentation of Cultural Heritage is communicated using Serious Games techniques in a story-centric immersive narration instead of an exhibit-centered presentation with the use of Gamification, Augmented and Virtual Reality technologies. In the introduction the authors present the project called ECHOES, in which knowledge about the past of Thessaloniki, Greece is planned to be processed as an immersive and interactive experience. After presenting related work and the methodology, the authors describe the proposed design of the Serious Game and close the article with a discussion and conclusions. The paper is interesting because it highlights an ongoing process in the realm of the visualization of Cultural Heritage (see for example Champion 2016). The process described by the authors on how to accomplish this by using Serious Games, Gamification, Augmented and Virtual Reality is promising, although still hypothetical as the project is ongoing. It remains to be seen if the proposed visuals and interactive elements will work in the way intended and offer users an immersive experience after all. A preliminary questionnaire already showed that most of the respondents were not familiar with these technologies (AR, VR) and in my experience these numbers only change slowly. One way to overcome the technological barrier however might be the gamification of the experience, which the authors are planning to implement. I decided to recommend this article based on the remarks of the two reviewers, which the authors implemented perfectly, as well as my own evaluation of the paper. Although still in progress it seems worthwhile to have this article as a basis for discussion and comparison to similar projects. However, the article did not mention the possible longevity of data and in which ways the usability of the Serious Game will be secured for long-term storage. One eminent problem in these endeavors is, that we can read about these projects, but never find them anywhere to test them ourselves (see for example Gabellone et al. 2016). It is my intention with this review and the recommendation, that the ECHOES project will find a solution for this problem and that we are not only able to read this (and forthcoming) article(s) about the ECHOES project, but also play the Serious Game they are proposing in the near and distant future. References

Gabellone, Francesco, Antonio Lanorte, Nicola Masini, und Rosa Lasaponara. 2016. „From Remote Sensing to a Serious Game: Digital Reconstruction of an Abandoned Medieval Village in Southern Italy“. Journal of Cultural Heritage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.01.012 Tsaknaki, Electra, Anastasovitis, Eleftherios, Georgiou, Georgia, Alagialoglou, Kleopatra, Mavrokostidou, Maria, Kartsiakli, Vasiliki, Aidonis, Asterios, Protopsalti, Tania, Nikolopoulos, Spiros, and Kompatsiaris, Ioannis. (2023). Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious Games, Zenodo, 7981323, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981323 | Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious Games | Tsaknaki, Electra; Anastasovitis, Eleftherios; Georgiou, Georgia; Alagialoglou, Kleopatra; Mavrokostidou, Maria; Kartsiakli, Vasiliki; Aidonis, Asterios; Protopsalti, Tania; Nikolopoulos, Spiros; Kompatsiaris, Ioannis | <p>The main challenge of the current digital transition is to utilize computing media and cutting-edge technologyin a more meaningful way, which would make the archaeological and anthropological research outcomes relevant to a heterogeneous audien... |  | Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Europe | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-05-29 13:19:46 | View | |

14 Nov 2023

Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics ClassroomStephan, Robert https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8221286Learning with Archaeogaming? A study based on student feedbackRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Jeremiah McCall and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jeremiah McCall and 1 anonymous reviewer

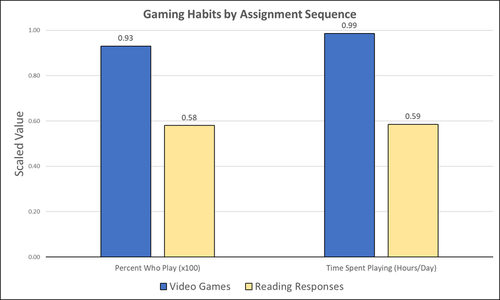

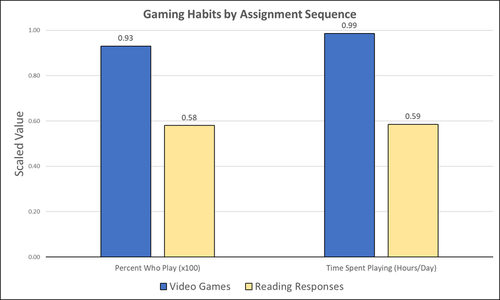

This paper (Stephan 2023) is about the use of video games as a pedagogical tool in class. Instead of taking the perspective of a lecturer, the author seeks the student’s perspectives to evaluate the success of an interactive teaching method at the crossroads of history, archaeology, and classics. The paper starts with a literature review, that highlights the intensive use of video games among college students and high schoolers as well as the impact video games can have on learning about the past. The case study this paper is based on is made with the game Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, which is introduced in the next part of the paper as well as previous works on the same game. The author then explains his method, which entailed the tasks students had to complete for a class in classics. They could either choose to play a video game or more classically read some texts. After the tasks were done, students filled out a 14-question-survey to collect data about prior gaming experience, assignment enjoyment, and other questions specific to the assignments. The results were based on only a fraction of the course participants (n=266) that completed the survey (n=26), which is a low number for doing statistical analysis. Besides some quantitative questions, students had also the possibility to freely give feedback on the assignments. Both survey types (quantitative answers and qualitative feedback) solely relied on the self-assessment of the students and one might wonder how representative a self-assessment is for evaluating learning outcomes. Both problems (size of the survey and actual achievements of learning outcomes) are getting discussed at the end of the paper, that rightly refers to its results as preliminary. I nevertheless think that this survey can help to better understand the role that video games can play in class. As the author rightly claims, this survey needs to be enhanced with a higher number of participants and a better way of determining the learning outcomes objectively. This paper can serve as a start into how we can determine the senseful use of video games in classrooms and what students think about doing so. References

Stephan, R. (2023). Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics Classroom, Zenodo, 8221286, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8221286

| Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics Classroom | Stephan, Robert | <p>This study assesses student feedback from the implementation of Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey as a teaching tool in a lower level, general education Classics course (CLAS 160B1 - Meet the Ancients: Gateway to Greece and Rome). In this course, which... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Mediterranean | Sebastian Hageneuer | Anonymous, Jeremiah McCall | 2023-08-07 16:45:31 | View |

11 Oct 2023

Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill ProjectSamanta Mariotti https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563Gamification of an archaeological park: The Living Hill Project as work-in-progressRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer

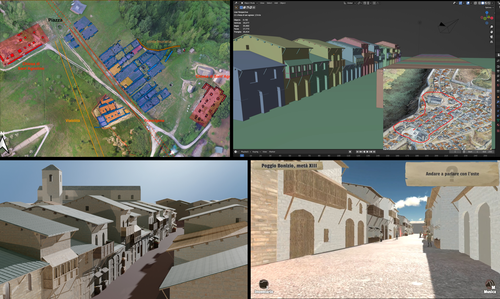

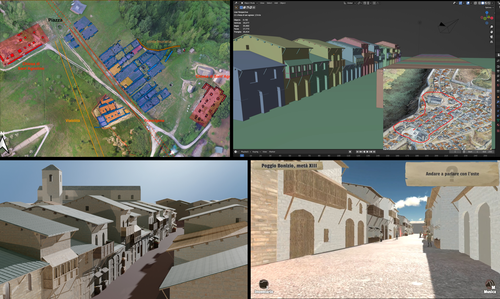

This paper (2023) describes The Living Hill project dedicated to the archaeological park and fortress of Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi, Italy. The project is a collaboration between the Poggibonsi excavation and Entertainment Games App, Ltd. From the start, the project focused on the question of the intended audience rather than on the used technology. It was therefore planned to involve the audience in the creation of the game itself, which was not possible after all due to the covid pandemic. Nevertheless, the game aimed towards a visit experience as close as possible to reality to offer an educational tool through the video game, as it offers more periods than the medieval period showcased in the archaeological park itself. The game mechanics differ from a walking simulator, or a virtual tour and the player is tasked with returning three lost objects in the virtual game. While the medieval level was based on a 3D scan of the archaeological park, the other two levels were reconstructed based on archaeological material. Currently, only a PC version is working, but the team works on a mobile version as well and teased the possibility that the source code will be made available open source. Lastly, the team also evaluated the game and its perception through surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Although the surveys were only based on 21 persons, the results came back positive overall. The paper is well-written and follows a consistent structure. The authors clearly define the goals and setting of the project and how they developed and evaluated the game. Although it has be criticized that the game is not playable yet and the size of the questionnaire is too low, the authors clearly replied to the reviews and clarified the situation on both matters. They also attended to nearly all of the reviewers demands and answered them concisely in their response. In my personal opinion, I can fully recommend this paper for publication. For future works, it is recommended that the authors enlarge their audience for the quesstionaire in order to get more representative results. It it also recommended to make the game available as soon as possible also outside of the archaeological park. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their concise and constructive criticism to this paper as well as for their time. References Mariotti, Samanta. (2023) Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project, Zenodo, 8302563, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563 | Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of *The Living Hill* Project | Samanta Mariotti | <p>Video games are now recognised as a valuable tool for disseminating and enhancing archaeological heritage. In Italy, the recent institutionalisation of Public Archaeology programs and incentives for digital innovation has resulted in a prolifer... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Europe, Medieval, Post-medieval | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-30 20:25:32 | View | |

03 Nov 2023

The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep InteractionMarco Callieri, Åsa Berggren, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Paola Derudas, Domenica Dininno, Fredrik Ekengren, Giuseppe Naponiello https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10067103A comparative teaching and learning tool for 3D data: Dynamic CollectionsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Louise Tharandt based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Louise Tharandt

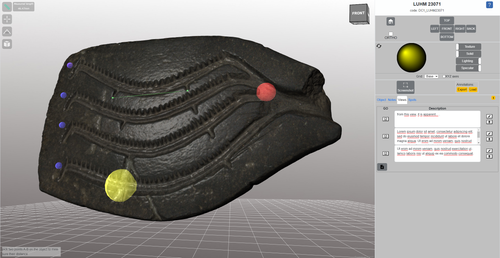

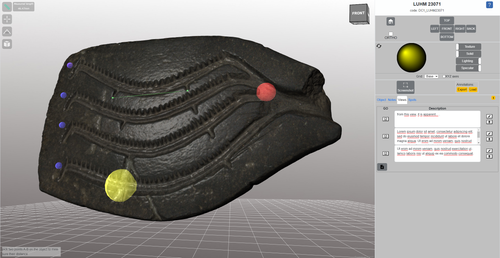

The paper (Callieri, M. et al. 2023) describes the “Dynamic Collections” project, an online platform initially created to showcase digital archaeological collections of Lund University. During a phase of testing by department members, new functionalities and artefacts were added resulting in an interactive platform adapted to university-level teaching and learning. The paper introduces into the topic and related works after which it starts to explain the project itself. The idea is to resemble the possibilities of interaction of non-digital collections in an online platform. Besides the objects themselves, the online platform offers annotations, measurement and other interactive tools based on the already known 3DHOP framework. With the possibility to create custom online collections a collaborative working/teaching environment can be created. The already wide-spread use of the 3DHOP framework enabled the authors to develop some functionalities that could be used in the “Dynamic Collections” project. Also, current and future plans of the project are discussed and will include multiple 3D models for one object or permanent identifiers, which are both important additions to the system. The paper then continues to explain some of its further planned improvements, like comparisons and support for teaching, which will make the tool an important asset for future university-level education. The paper in general is well-written and informative and introduces into the interactive tool, that is already available and working. It is very positive, that the authors rely on up-to-date methodologies in creating 3D online repositories and are in fact improving them by testing the tool in a teaching environment. They mention several times the alignment with upcoming EU efforts related to the European Collaborative Cloud for Cultural Heritage (ECCCH), which is anticipatory and far-sighted and adds to the longevity of the project. Comments of the reviewers were reasonably implemented and led to a clearer and more concise paper. I am very confident that this tool will find good use in heritage research and presentation as well as in university-level teaching and learning. Although the authors never answer the introductory question explicitly (What characteristics should a virtual environment have in order to trigger dynamic interaction?), the paper gives the implicit answer by showing what the "Dynamic Collections" project has achieved and is able to achieve in the future. BibliographyCallieri, M., Berggren, Å., Dell'Unto, N., Derudas, P., Dininno, D., Ekengren, F., and Naponiello, G. (2023). The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep Interaction, Zenodo, 10067103, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10067103 | The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep Interaction | Marco Callieri, Åsa Berggren, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Paola Derudas, Domenica Dininno, Fredrik Ekengren, Giuseppe Naponiello | <p>The Dynamic Collections project is an ongoing initiative pursued by the Visual Computing Lab ISTI-CNR in Italy and the Lund University Digital Archaeology Laboratory-DARKLab, Sweden. The aim of this project is to explore the possibilities offer... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-31 15:05:32 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3DFlorian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269A valuable contribution to automated analysis of palaeolithic artefactsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper (Linsel/Bullenkamp/Mara 2024), the authors propose an automatic system for scar-ridge-pattern detection on palaeolithic artefacts based on Morse Theory. Scare-Ridge pattern recognition is a process that is usually done manually while creating a drawing of the object itself. Automatic systems to detect scars or ridges exist, but only a small amount of them is utilizing 3D data. In addition to the scar-ridges detection, the authors also experiment in automatically detecting the operational sequence, the temporal relation between scars and ridges. As a result, they can export a traditional drawing as well as graph models displaying the relationships between the scars and ridges. After an introduction to the project and the practice of documenting palaeolithic artefacts, the authors explain their procedure in automatising the analysis of scars and ridges as well as their temporal relation to each other on these artefacts. To illustrate the process, an open dataset of lithic artefacts from the Grotta di Fumane, Italy, was used and 62 artefacts selected. To establish a Ground Truth, the artefacts were first annotated manually. The authors then continue to explain in detail each step of the automated process that follows and the results obtained. In the second part of the paper, the results are presented. First the results of the segmentation process shows that the average percentage of correctly labelled vertices is over 91%, which is a remarkable result. The graph modelling however shows some more difficulties, which the authors are aware of. To enhance the process, the authors rightfully aim to include datasets of experimental archaeology in the future. They also aim to develop a way of detecting the operational sequence automatically and precisely. This paper has great potential as it showcases exactly what Digital and Computational Archaeology is about: The development of new digital methods to enhance the analysis of archaeological data. While this procedure is still in development, the authors were able to present a valuable contribution to the automatization of analytical archaeology. By creating a step towards the machine-readability of this data, they also open up the way to further steps in machine learning within Archaeology. BibliographyLinsel, F., Bullenkamp, J. P., and Mara, H. (2024). Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D, Zenodo, 8296269, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269 | Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D | Florian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara | <p>Motivated by the concept of combining the archaeological practice of creating lithic artifact drawings with the potential of 3D mesh data, our goal in this project is not only to analyze the shape at the artifact level, but also to enable a mor... | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Upper Palaeolithic | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-09-01 23:03:59 | View | ||

16 May 2024

A return to function as the basis of lithic classificationRadu Iovita https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7734147Using insights from psychology and primatology to reconsider function in lithic typologiesRecommended by Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Vincent Delvigne and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Vincent Delvigne and 1 anonymous reviewer

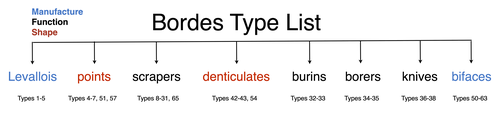

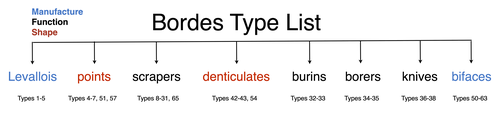

The paper “A return to function as the basis of lithic classification” by Radu Iovita (2024) is a contribution to an upcoming volume on the role of typology and type-thinking in current archaeological theory and praxis edited by the PCI recommenders. In this context, the paper offers an in-depth discussion of several crucial dimensions of typological thinking in past and current lithic studies, namely:

Discussing and importantly re-articulating these concepts, Iovita ultimately aims at “establishing unified guiding principles for studying a technology that spans several million years and several different species whose brain capacities range from ca. 300–1400 cm³”. The notion that tool function should dictate classification is not new (e.g. Gebauer 1987). It is particularly noteworthy, however, that the paper engages carefully with various relevant contributions on the topic from non-Anglophone research traditions. First, its considering works on lithic typologies published in other languages, such as Russian (Sergei Semenov), French (Georges Laplace), and German (Joachim Hahn). Second, it takes up the ideas of two French techno-anthropologists, in particular:

Interestingly, Iovita grounds his argumentation on insights from primatology, psychology and the cognitive sciences, to the extent that they fuel discussion on archaeological concepts and methods. Results regarding the so-called “design stance” for example play a crucial role: coined by philosopher and cognitive scientist and philosopher Daniel Dennett (1942-2024), this notion encompasses the possible discrepancies between the designer’s intended purpose and the object's current functions. DIF, as discussed by Iovita, directly relates to this idea, illustrating how concepts from other sciences can fruitfully be injected into archaeological thinking. Lastly, readers should note the intellectual contents generated on PCI as part of the reviewing process of the paper itself: both the reviewers and the author have engaged in in-depth discussions on the idea of (tool) “function” and its contested relationship with form or typology, delineating and mapping different views on these key issues in lithic study which are worth reading on their own. ReferencesGebauer, A. B. (1987). Stylistic Analysis. A Critical Review of Concepts, Models, and Interpretations, Journal of Danish Archaeology, 6, p. 223–229. Geertz, C. (1975). Common Sense as a Cultural System, The Antioch Review, 33 (1), p. 5–26. Iovita, R. (2024). A return to function as the basis of lithic classification. Zenodo, 7734147, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7734147 Lévi-Strauss, C. (1962). La pensée sauvage. Paris: Plon. Lévi-Strauss, C. (2021). Wild Thought: A New Translation of “La Pensée sauvage”. Translated by Jeffrey Mehlman & John Leavitt. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l'analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d'études technologiques en préhistoire : Bilan et perspectives, Juan-les-Pins: Éditions de l'association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques, p. 21-34. | A return to function as the basis of lithic classification | Radu Iovita | <p>Complex tool use is one of the defining characteristics of our species, and, because of the good preservation of stone tools (lithics), one of the few which can be studied on the evolutionary time scale. However, a quick look at the lithics lit... |  | Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Theoretical archaeology, Traceology | Sébastien Plutniak | 2023-03-14 19:01:40 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Automation and Novelty –Archaeocomputational Typo-Praxis in the Wake of the Third Science RevolutionRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Rachel Crellin and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Rachel Crellin and 1 anonymous reviewer

“Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology” submitted by G. Lucas (1) offers a refreshing and welcome reflection on the role of computer-based practice, type-thinking and approaches to typology in the age of big data and the widely proclaimed ‘Third Science Revolution’ (2–4). At the annual meeting of the EAA in Maastricht in 2017, a special thematic block was dedicated to issues and opportunities linked to the Third Science Revolution in archaeology “because of [its] profound and wide ranging impact on practice and theory in archaeology for the years to come” (5). Even though the Third Science Revolution, as influentially outlined by Kristiansen in 2014 (2), has occasionally also been met with skepticism and critique as to its often implicit scientism and epistemological naivety (6–8), archaeology as a whole seems largely euphoric as to the promises of the advancing ‘revolution’. As Lucas perceptively points out, some even regard it as the long-awaited opportunity to finally fulfil the ambitions and goals of Anglophone processualism. The irony here, as Lucas rightly notes, is that early processualists initially foregrounded issues of theory and scientific epistemology, while much work conducted under the banner of the Third Science Revolution, especially within its computational branches, does not. Big data advocates have echoed Anderson’s much-cited “end of theory” (9) or at least emphatically called for an ‘empirization’ and ‘computationalization’ of theory, often under the banner of ‘data-driven archaeology’ (10), yet typically without much specification of what this is supposed to mean for archaeological theory and reflexivity. The latter is indeed often openly opposed by archaeological Third Science Revolution enthusiasts, arguably because it is viewed as part of the supposedly misguided ‘post-modernist’ project. Lucas makes an original meta-archaeological contribution here and attempts to center the epistemological, ontological and praxeological dimensions of what is actually – in situated archaeological praxis and knowledge-production – put at stake by the mobilization of computers, algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI), including its many but presently under-reflected implications for ordering practices such as typologization. Importantly, his perspective thereby explicitly and deliberately breaks with the ‘normative project’ in traditional philosophy of science, which sought to nail down a universal, prescriptive way of doing science and securing scientific knowledge. He instead focuses on the practical dimensions and consequences of computer-reliant archaeologies, what actually happens on the ground as researchers try to grapple with the digital and the artefactual and try to negotiate new insights and knowledge, including all of the involved messiness – thereby taking up the powerful impetus of the broader practice turn in interdisciplinary science studies and STS (Science and Technology Studies (11)) (12–14), which have recently also re-oriented archaeological self-observation, metatheory and epistemology (15). This perspective on the dawning big data age in archaeology and incurred changes in the status, nature and aims of type-thinking produces a number of important insights, which Lucas fruitfully discusses in relation to promises of ‘automation’ and ‘novelty’ as these feature centrally in the rhetorics and politics of the Third Science Revolution. With regard to automation, Lucas makes the important point that machine or computer work as championed by big data proponents cannot adequately be qualified or understood if we approach the issue from a purely time-saving perspective. The question we have to ask instead is what work do machines actually do and how do they change the dynamics of archaeological knowledge production in the process? In this optic, automation and acceleration achieved through computation appear to make most sense in the realm of the uncontroversial, in terms of “reproducing an accepted way of doing things” as Lucas says, and this is precisely what can be observed in archaeological practice as well. The ramifications of this at first sight innocent realization are far-reaching, however. If we accept the noncontroversial claim that automation partially bypasses the need for specialists through the reproduction of already “pre-determined outputs”, automated typologization would primarily be useful in dealing with and synthesizing larger amounts of information by sorting artefacts into already accepted types rather than create novel types or typologies. If we identity the big data promise at least in part with automation, even the detection of novel patterns in any archaeological dataset used to construct new types cannot escape the fact that this novelty is always already prefigured in the data structure devised. The success of ‘supervised learning’ in AI-based approaches illustrates this. Automation thus simply shifts the epistemological burden back to data selection and preparation but this is rarely realized, precisely because of the tacit requirement of broad non-contentiousness. Minimally, therefore, big data approaches ironically curtail their potential for novelty by adhering to conventional data treatment and input formats, rarely problematizing the issue of data construction and the contested status of (observational) data themselves. By contrast, they seek to shield themselves against such attempts and tend to retain a tacit universalism as to the nature of archaeological data. Only in this way is it possible to claim that such data have the capacity to “speak for themselves”. To use a concept borrowed from complexity theory, archaeological automation-based type-construction that relies on supposedly basal, incontrovertible data inputs can only ever hope to achieve ‘weak emergence’ (16) – ‘strong emergence’ and therefore true, radical novelty require substantial re-thinking of archaeological data and how to construct them. This is not merely a technical question as sometimes argued by computational archaeologies – for example with reference to specifically developed, automated object tracing procedures – as even such procedures cannot escape the fundamental question of typology: which kind of observations to draw on in order to explore what aspects of artefactual variability (and why). The focus on readily measurable features – classically dimensions of artefactual form – principally evades the key problem of typology and ironically also reduces the complexity of artefactual realities these approaches assert to take seriously. The rise of computational approaches to typology therefore reintroduces the problem of universalism and, as it currently stands, reduces the complexity of observational data potentially relevant for type-construction in order to enable to exploration of the complexity of pattern. It has often been noted that this larger configuration promotes ‘data fetishism’ and because of this alienates practitioners from the archaeological record itself – to speak with Marxist theory that Lucas briefly touches upon. We will briefly return to the notion of ‘distance’ below because it can be described as a symptomatic research-logical trope (and even a goal) in this context of inquiry. In total, then, the aspiration for novelty is ultimately difficult to uphold if computational archaeologies refuse to engage in fundamental epistemological and reflexive self-engagement. As Lucas poignantly observes, the most promising locus for novelty is currently probably not to be found in the capacity of the machines or algorithms themselves, but in the modes of collaboration that become possible with archaeological practitioners and specialists (and possibly diverse other groups of knowledge stakeholders). In other words, computers, supercomputers and AI technologies do not revolutionize our knowledge because of their superior computational and pattern-detection capacities – or because of some mysterious ‘superintelligence’ – but because of the specific ‘division of labour’ they afford and the cognitive challenge(s) they pose. Working with computers and AI also often requires to ask new questions or at least to adapt the questions we ask. This can already be seen on the ground, when we pay attention to how machine epistemologies are effectively harnessed in archaeological practice (and is somewhat ironic given that the promise of computational archaeology is often identified with its potential to finally resolve "long-standing (old) questions"). The Third Science Revolution likely prompts a consequential transformation in the structural and material conditions of the kinds of ‘distributed’ processes of knowledge production that STS have documented as characteristic for scientific discoveries and knowledge negotiations more generally (14, 17, 18). This ongoing transformation is thus expected not only to promote new specializations with regard to the utilization of the respective computing infrastructures emerging within big data ecologies but equally to provoke increasing demand for new ways of conceptualizing observations and to reformulate the theoretical needs and goals of typology in archaeology. The rediscovery of reflexivity as an epistemic virtue within big data debates would be an important step into this direction, as it would support the shared goal of achieving true epistemic novelty, which, as Lucas points out, is usually not more than an elusive self-declaration. Big data infrastructures require novel modes of human-machine synergy, which simply cannot be developed or cultivated in an atheoretical and/or epistemological disinterested space. Lucas’ exploration ultimately prompts us to ask big questions (again), and this is why this is an important contribution. The elephant in the room, of course, is the overly strong notion of objectivity on which much computational archaeology is arguably premised – linked to the vow to eventually construct ‘objective typologies’. This proclivity, however, re-tables all the problematic debates of the 1960s and – to speak with the powerful root metaphor of the machine fueling much of causal-mechanistic science (19, 20) – is bound to what A. Wylie (21) and others have called the ‘view from nowhere’. Objectivity, in this latter view, is defined by the absence of positionality and subjectivity – chiefly human subjectivity – and the promise of the machine, and by extension of computational archaeology, is to purify and thus to enhance processes of knowledge production by minimizing human interference as much as possible. The distancing of the human from actual processes of data processing and inference is viewed as positive and sometimes even as an explicit goal of scientific development. Interestingly, alienation from the archaeological record is framed as an epistemic virtue here, not as a burden, because close connection with (or even worse, immersion in) the intricacies of artefacts and archaeological contexts supposedly aggravates the problem of bias. The machine, in this optic, is framed as the gatekeeper to an observer-independent reality – which to the backdoor often not only re-introduces Platonian/Aristotelian pledges to a quasi-eternal fabric of reality that only needs to be “discovered” by applying the right (broadly nonhuman) means, it is also largely inconsistent with defendable and currently debated conceptions of scientific objectivity that do not fall prey to dogma. Furthermore, current discussions on the open AI ChatGPT have exposed the enormous and still under-reflected dangers of leaning into radical renderings of machine epistemology: precisely because of the principles of automation and the irreducible theory-ladenness of all data, ecologies such as ChatGPT tend to reinforce the tacit epistemological background structures on which they operate and in this way can become collaborators in the legitimization and justification of the status quo (which again counteracts the potential for novelty) – they reproduce supposedly established patterns of thought. This is why, among other things, machines and AI can quickly become perpetuators of parochial and neocolonial projects – their supposed authority creates a sense of impartiality that shields against any possible critique. With Lucas, we can thus perhaps cautiously say that what is required in computational archaeology is to defuse the authority of the machine in favour of a new community archaeology that includes machines as (fallible) co-workers. Radically put, computers and AI should be recognized as subjects themselves, and treated as such, with interesting perspectives on team science and collaborative practice.

Bibliography 1. Lucas, G. (2022). Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology. https:/doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7620824. 2. Kristiansen, K. (2014). Towards a New Paradigm? The Third Science Revolution and its Possible Consequences in Archaeology. Current Swedish Archaeology 22, 11–34. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2014.01. 3. Kristiansen, K. (2022). Archaeology and the Genetic Revolution in European Prehistory. Elements in the Archaeology of Europe. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009228701 4. Eisenhower, M. S. (1964). The Third Scientific Revolution. Science News 85, 322/332. https://www.sciencenews.org/archive/third-scientific-revolution. 5. The ‘Third Science Revolution’ in Archaeology. http://www.eaa2017maastricht.nl/theme4 (March 16, 2023). 6. Ribeiro, A. (2019). Science, Data, and Case-Studies under the Third Science Revolution: Some Theoretical Considerations. Current Swedish Archaeology 27, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2019.06 7. Samida, S. (2019). “Archaeology in times of scientific omnipresence” in Archaeology, History and Biosciences: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, pp. 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110616651 8. Sørensen, T. F.. (2017). The Two Cultures and a World Apart: Archaeology and Science at a New Crossroads. Norwegian Archaeological Review 50, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2017.1367031 9. Anderson, C. (2008). The end of theory: The data deluge makes the scientific method obsolete. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/. 10. Gattiglia, G. (2015). Think big about data: Archaeology and the Big Data challenge. Archäologische Informationen 38, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.11588/ai.2015.1.26155 11. Hackett, E. J. (2008). The handbook of science and technology studies, Third edition, MIT Press/Society for the Social Studies of Science. 12. Ankeny, R., Chang, H., Boumans, M. and Boon, M. (2011). Introduction: philosophy of science in practice. Euro Jnl Phil Sci 1, 303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-011-0036-4 13. Soler, L., Zwart, S., Lynch, M., Israel-Jost, V. (2014). Science after the Practice Turn in the Philosophy, History, and Social Studies of Science, Routledge. 14. Latour, B. and Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: the construction of scientific facts, Princeton University Press. 15. Chapman, R. and Wylie, A. (2016) Evidential reasoning in archaeology, Bloomsbury Academic. 16. Greve, J. and Schnabel, A. (2011). Emergenz: zur Analyse und Erklärung komplexer Strukturen, Suhrkamp. 17. Shapin, S., Schaffer, S. and Hobbes, T. (1985). Leviathan and the air-pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life, including a translation of Thomas Hobbes, Dialogus physicus de natura aeris by Simon Schaffer, Princeton University Press. 18. Galison, P. L. and Stump, D. J. (1996).The Disunity of Science: Boundaries, Contexts, and Power, Stanford University Press. 19. Pepper, S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print, University of California Press. 20. Hussain, S. T. (2019). The French-Anglophone divide in lithic research: A plea for pluralism in Palaeolithic Archaeology, Open Access Leiden Dissertations. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/69812 21. A. Wylie, A. (2015). “A plurality of pluralisms: Collaborative practice in archaeology” in Objectivity in Science, pp. 189-210, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14349-1_10 | Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology | Gavin Lucas | <p>In this paper, I will explore some of the implications of machine learning for archaeological method and theory. Against a back-drop of the rise of Big Data and the Third Science Revolution, what lessons can be drawn from the use of new digital... | Computational archaeology, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | Anonymous, Rachel Crellin | 2022-10-31 15:25:38 | View | |

02 Dec 2023

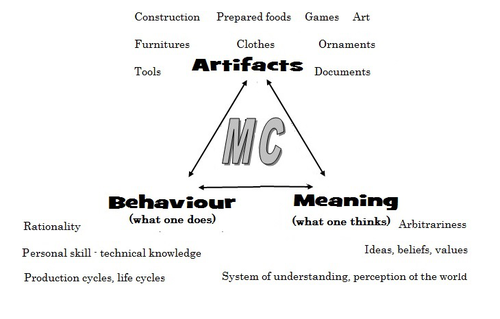

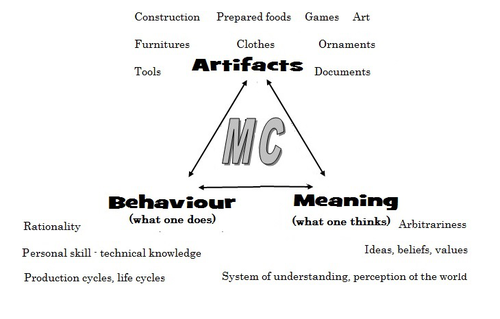

Research perspectives and their influence for typologiesEnrico Giannichedda https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7322855Complexity and Purpose – A Pragmatic Approach to the Diversity of Archaeological Classificatory Practice and TypologyRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Ulrich Veit, Martin Hinz, Artur Ribeiro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ulrich Veit, Martin Hinz, Artur Ribeiro and 1 anonymous reviewer

“Research perspectives and their influence for typologies” by E. Giannichedda (1) is a contribution to the upcoming volume on the role of typology and type-thinking in current archaeological theory and praxis edited by the recommenders. Taking a decidedly Italian perspective on classificatory practice grounded in what the author dubs the “history of material culture”, Giannichedda offers an inventory of six divergent but overall complementary modes of ordering archaeological material: i) chrono-typological and culture-historical, ii) techno-anthropological, iii) social, iv) socio-economic and v) cognitive. These various lenses broadly align with similarly labeled perspectives on the archaeological record more generally. According to the author, they lend themselves to different ways of identifying and using types in archaeological work. Importantly, Giannichedda reminds us that no ordering practice is a neutral act and typologies should not be devised for their own sake but because we have specific epistemic interests. Even though this view is certainly not shared by everyone involved in the broader debate on the purpose and goal of systematics, classification, typology or archaeological taxonomy (2–4), the paper emphatically defends the long-standing idea that ordering practices are not suitable to elucidate the structure and composition of reality but instead devise tools to answer certain questions or help investigate certain dimensions of complex past realities. This position considers typologies as conceptual prosthetics of knowing, a view that broadly resonates with what is referred to as epistemic instrumentalism in the philosophy of science (5, 6). Types and type-work should accordingly reflect well-defined means-end relationships. Based on the recognition of archaeology as part of an integrated “history of material culture” rooted in a blend of continental and Anglophone theories, Giannichedda argues that type-work should pay attention to relevant relations between various artefacts in a given historical context that help further historical understanding. Classificatory practice in archaeology – the ordering of artefactual materials according to properties – must thus proceed with the goal of multifaceted “historical reconstruction in mind”. It should serve this reconstruction, and not the other way around. By drawing on the example of a Medieval nunnery in the Piedmont region of northwestern Italy, Giannichedda explores how different goals of classification and typo-praxis (linked to i-v; see above) foreground different aspects, features, and relations of archaeological materials and as such allow to pinpoint and examine different constellations of archaeological objects. He argues that archaeological typo-praxis, for this reason, should almost never concern itself with isolated artefacts but should take into account broader historical assemblages of artefacts. This does not necessarily mean to pay equal attention to all available artefacts and materials, however. To the contrary, in many cases, it is necessary to recognize that some artefacts and some features are more important than others as anchors grouping materials and establishing relations with other objects. An example are so-called ‘barometer objects’ (7) or unique pieces which often have exceptional informational value but can easily be overlooked when only shared features are taken into consideration. As Giannichedda reminds us, considering all objects and properties equally is also a normative decision and does not render ordering less subjective. The archaeological analysis of types should therefore always be complemented by an examination of variants, even if some of these variants are idiosyncratic or even unique. A type, then, may be difficult to define universally. In total, “Research perspectives and their influence for typologies” emphasizes the need for “elastic” and “flexible” approaches to archaeological types and typologies in order to effectively respond to the manifold research interests cultivated by archaeologists as well as the many and complex past realities they face. Complexity is taken here to indicate that no single research perspective and associated mode of ordering can adequately capture the dimensionality and richness of these past realities and we can therefore only benefit from multiple co-existing ways of grouping and relating archaeological artefacts. Different logics of grouping may simply reveal different aspects of these realities. As such, Giannichedda’s proposal can be read as a formulation of the now classic pluralism thesis (8–11) – that only a plurality of ways of ordering and interrelating artefacts can unlock the full suite of relationships within historical assemblages archaeologists are interested in.

Bibliography 1. Giannichedda, E. (2023). Research perspectives and their influence for typologies, Zenodo, 7322855, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7322855 2. Dunnell, R. C. (2002). Systematics in Prehistory, Illustrated Edition (The Blackburn Press, 2002). 3. Reynolds, N. and Riede, F. (2019). House of cards: cultural taxonomy and the study of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Antiquity 93, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.49 4. Lyman, R. L. (2021). On the Importance of Systematics to Archaeological Research: the Covariation of Typological Diversity and Morphological Disparity. J Paleo Arch 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00077-6 5. Van Fraassen, B. C. (2002). The empirical stance (Yale University Press). 6. Stanford, P. K. (2006). Exceeding Our Grasp: Science, History, and the Problem of Unconceived Alternatives (Oxford University Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/0195174089.001.0001 7. Radohs, L. (2023). Urban elite culture: a methodological study of aristocracy and civic elites in sea-trading towns of the southwestern Baltic (12th-14th c.) (Böhlau). 8. Kellert, S. H., Longino, H. E. and Waters, C. K. (2006). Scientific pluralism (University of Minnesota Press). 9. Cat, J. (2012). Essay Review: Scientific Pluralism. Philosophy of Science 79, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/664747 10. Chang, H. (2012). Is Water H2O?: Evidence, Realism and Pluralism (Springer Netherlands). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3932-1 11. Wylie, A. (2015). “A plurality of pluralisms: Collaborative practice in archaeology” in Objectivity in Science, (Springer), pp. 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14349-1_10

| Research perspectives and their influence for typologies | Enrico Giannichedda | <p>This contribution opens with a brief reflection on theoretical archaeology and practical material classification activities. Following this, the various questions that can be asked of artefacts to be classified will be briefly addressed. Questi... |  | Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2022-11-10 20:14:52 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer