Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 Mar 2024

What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery.Philippe Boissinot https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433Abstract and Concrete – Querying the Metaphysics and Geometry of Pottery ClassificationRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

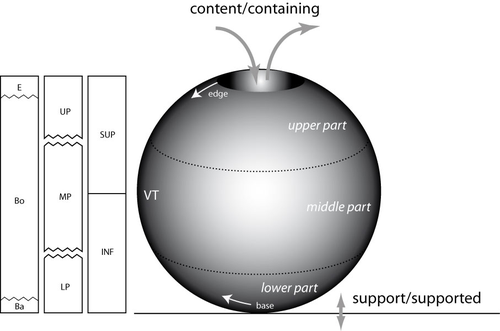

“What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery” by P. Boissinot (1) is a timely contribution to broader theoretical reflections on classification and ordering practices in archaeology, including type-construction and justification. Boissinot rightly reminds us that engagement with the type concept always touches upon the uneasy relationship between the abstract and the concrete, alternatively cast as the ongoing struggle in knowledge production between idealization and particularization. Types are always abstract and as such both ‘more’ and ‘less’ than the concrete objects they refer to. They are ‘more’ because they establish a higher-order identity of variously heterogeneous, concrete objects and they are ‘less’ because they necessarily reduce the richness of the concrete and often erase it altogether. The confusion that types evoke in archaeology and elsewhere has therefore a lot to do with the fact that types are simply not spatiotemporally distinct particulars. As abstract entities, types so almost automatically re-introduce the question of universalism but they do not decide this question, and Boissinot also tentatively rejects such ambitions. In fact, with Boissinot (1) it may be said that universality is often precisely confused with idealization, which is indispensable to all archaeological ordering practices. Idealization, increasingly recognized as an important epistemic operation in science (2, 3), paradoxically revolves around the deliberate misrepresentation of the empirical systems being studied, with models being the paradigm cases (4). Models can go so far as to assume something strictly false about the phenomena under consideration in order to advance their epistemic goals. In the words of Angela Potochnik (5), ‘the role of idealization in securing understanding distances understanding from truth but […] this understanding nonetheless gives rise to scientific knowledge’. The affinity especially to models may in part explain why types are so controversial and are often outright rejected as ‘real’ or ‘useful’ by those who only recognize the existence of concrete particulars (nominalism). As confederates of the abstract, types thus join the ranks of mathematics and geometry, which the author identifies as prototypical abstract systems. Definitions are also abstract. According to Boissinot (1), they delineate a ‘position of limits’, and the precision and rigorousness they bring comes at the cost of subjectivity. This unites definitions and types, as both can be precise and clear-cut but they can never be strictly singular or without alternative – in order to do so, they must rely on yet another higher-order system of external standards, and so ad infinitum. Boissinot (1) advocates a mathematical and thus by definition abstract approach to archaeological type-thinking in the realm of pottery, as the abstractness of this approach affords relatively rigorous description based on the rules of geometry. Importantly, this choice is not a mysterious a priori rooted in questionable ideas about the supposed superiority of such an approach but rather is the consequence of a careful theoretical exploration of the particularities (domain-specificities) of pottery as a category of human practice and materiality. The abstract thus meets the concrete again: objects of pottery, in sharp contrast to stone artefacts for example, are the product of additive processes. These processes, moreover, depend on the ‘fusion’ of plastic materials and the subsequent fixation of the resulting configuration through firing (processes which, strictly speaking, remove material, such as stretching, appear to be secondary vis-à-vis global shape properties). Because of this overriding ‘fusion’ of pottery, the identification of parts, functional or otherwise, is always problematic and indeterminate to some extent. As products of fusion, parts and wholes represent an integrated unity, and this distinguishes pottery from other technologies, especially machines. The consequence is that the presence or absence of parts and their measurements may not be a privileged locus of type-construction as they are in some biological contexts for example. The identity of pottery objects is then generally bound to their fusion. As a ‘plastic montage’ rather than an assembly of parts, individual parts cannot simply be replaced without threatening the identity of the whole. Although pottery can and must sometimes be repaired, this renders its objects broadly morpho-static (‘restricted plasticity’) rather than morpho-dynamic, which is a condition proper to other material objects such as lithic (use and reworking) and metal artefacts (deformation) but plays out in different ways there. This has a number of important implications, namely that general shape and form properties may be expected to hold much more relevant information than in technological contexts characterized by basal modularity or morpho-dynamics. It is no coincidence that ‘fusion’ is also emphasized by Stephen C. Pepper (6) as a key category of what he calls contextualism. Fusion for Pepper pays dividends to the interpenetration of different parts and relations, and points to a quality of wholes which cannot be reduced any further and integrates the details into a ‘more’. Pepper maintains that ‘fusion, in other words, is an agency of simplification and organization’ – it is the ‘ultimate cosmic determinator of a unit’ (p. 243-244, emphasis added). This provides metaphysical reasons to look at pottery from a whole-centric perspective and to foreground the agency of its materiality. This is precisely what Boissinot (1) does when he, inspired by the great techno-anthropologist François Sigaut (7), gestures towards the fact that elementarily a pot is ‘useful for containing’. He thereby draws attention not to the function of pottery objects but to what pottery as material objects do by means of their material agency: they disclose a purposive tension between content and container, the carrier and carried as well as inclusion and exclusion, which can also be understood as material ‘forces’ exerted upon whatever is to be contained. This, and not an emic reading of past pottery use, leads to basic qualitative distinctions between open and closed vessels following Anna O. Shepard’s (8) three basic pottery categories: unrestricted, restricted, and necked openings. These distinctions are not merely intuitive but attest to the object-specificity of pottery as fused matter. This fused dimension of pottery also leads to a recognition that shapes have geometric properties that emerge from the forced fusion of the plastic material worked, and Boissinot (1) suggests that curvature is the most prominent of such features, which can therefore be used to describe ‘pure’ pottery forms and compare abstract within-pottery differences. A careful mathematical theorization of curvature in the context of pottery technology, following George D. Birkhoff (9), in this way allows to formally distinguish four types of ‘geometric curves’ whose configuration may serve as a basis for archaeological object grouping. The idealization involved in this proposal is not accidental but deliberately instrumental – it reminds us that type-thinking in archaeology cannot escape the abstract. It is notable here that the author does not suggest to simply subject total pottery form to some sort of geometric-morphometric analysis but develops a proposal that foregrounds a limited range of whole-based geometric properties (in contrast to part-based) anchored in general considerations as to the material specificity of pottery as quasi-species of objects. As Boissinot (1) notes himself, this amounts to a ‘naturalization’ of archaeological artefacts and offers somewhat of an alternative (a third way) to the old discussion between disinterested form analysis and functional (and thus often theory-dependent) artefact groupings. He thereby effectively rejects both of these classic positions because the first ignores the particularities of pottery and the real function of artefacts is in most cases archaeologically inaccessible. In this way, some clear distance is established to both ethnoarchaeology and thing studies as a project. Attending to the ‘discipline of things’ proposal by Bjørnar Olsen and others (10, 11), and by drawing on his earlier work (12), Boissinot interestingly notes that archaeology – never dealing with ‘complete societies’ – could only be ‘deficient’. This has mainly to do with the underdetermination of object function by the archaeological record (and the confusion between function and functionality) as outlined by the author. It seems crucial in this context that Boissinot does not simply query ‘What is a thing?’ as other thing-theorists have previously done, but emphatically turns this question into ‘In what way is it not the same as something else?’. He here of course comes close to Olsen’s In Defense of Things insofar as the ‘mode of being’ or the ‘ontology’ of things is centred. What appears different, however, is the emphasis on plurality and within-thing heterogeneity on the level of abstract wholes. With Boissinot, we always have to speak of ontologies and modes of being and those are linked to different kinds of things and their material specificities. Theorizing and idealizing these specificities are considered central tasks and goals of archaeological classification and typology. As such, this position provides an interesting alternative to computational big-data (the-more-the-better) approaches to form and functionally grounded type-thinking, yet it clearly takes side in the debate between empirical and theoretical type-construction as essential object-specific properties in the sense of Boissinot (1) cannot be deduced in a purely data-driven fashion. Boissinot’s proposal to re-think archaeological types from the perspective of different species of archaeological objects and their abstract material specificities is thought-provoking and we cannot stop wondering what fruits such interrogations would bear in relation to other kinds of objects such as lithics, metal artefacts, glass, and so forth. In addition, such meta-groupings are inherently problematic themselves, and they thus re-introduce old challenges as to how to separate the relevant super-wholes, technological genesis being an often-invoked candidate discriminator. The latter may suggest that we cannot but ultimately circle back on the human context of archaeological objects, even if we, for both theoretical and epistemological reasons, wish to embark on strictly object-oriented archaeologies in order to emancipate ourselves from the ‘contamination’ of language and in-built assumptions.

Bibliography 1. Boissinot, P. (2024). What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery, Zenodo, 7429330, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433 2. Fletcher, S.C., Palacios, P., Ruetsche, L., Shech, E. (2019). Infinite idealizations in science: an introduction. Synthese 196, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02069-6 3. Potochnik, A. (2017). Idealization and the aims of science (University of Chicago Press). https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226507194.001.0001 4. J. Winkelmann, J. (2023). On Idealizations and Models in Science Education. Sci & Educ 32, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00291-2 5. Potochnik, A. (2020). Idealization and Many Aims. Philosophy of Science 87, 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1086/710622 6. Pepper S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (University of California Press). 7. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l’analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d’études Technologiques En Préhistoire. Bilan et Perspectives (Association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques), pp. 21–34. 8. Shepard, A. O. (1956). Ceramics for the Archeologist (Carnegie Institution of Washington n° 609). 9. Birkhoff G. D. (1933). Aesthetic Measure (Harvard University Press). 10. Olsen, B. (2010). In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects (AltaMira Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/ept014 11. Olsen, B., Shanks, M., Webmoor, T., Witmore, C. (2012). Archaeology: the discipline of things (University of California Press). https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520954007 12. Boissinot, P. (2011). “Comment sommes-nous déficients ?” in L’archéologie Comme Discipline ? (Le Seuil), pp. 265–308. | What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery. | Philippe Boissinot | <p>The main question we want to ask here concerns the application of philosophical considerations on identity about artifacts of a particular kind (pottery). The purpose is the recognition of types and their classification, which are two of the ma... |  | Ceramics, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2022-12-13 15:04:45 | View | |

05 Jan 2024

The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A Website Approach to Archaeological Typology.Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7743834Roster and Lexicon – A Radical Digital-Dialogical Approach to Questions of Typology and Categorization in ArchaeologyRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and 2 anonymous reviewers

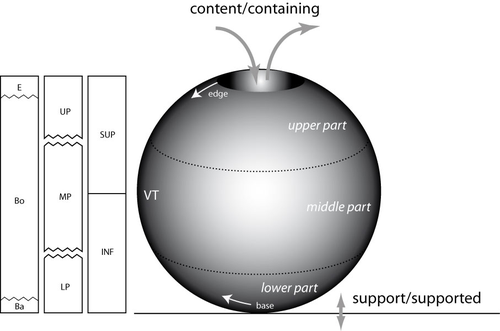

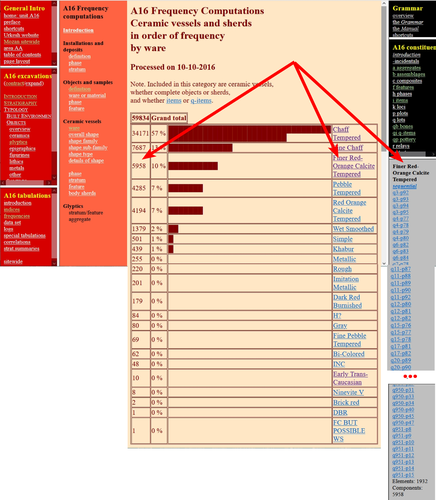

“The density of types and the dignity of the fragment. A website approach to archaeological typology” by G. Buccellati and M. Kelly-Buccellati (1) is a contribution to the rapidly growing literature on digital approaches to archaeological data management, expertly showcasing the significant theoretical and epistemological impetus of such work. The authors offer a conceptually lucid discussion of key concepts in archaeological ordering practices surrounding the longstanding tension between so-called ‘etic’ and ‘emic’ approaches, thereby providing a thorough systematic of how to think through sameness and difference in the context of voluminous digital archaeological data. As a point of departure, the authors reconsider the relationship between archaeological fragments – spatiotemporally bounded artefacts and features – and their larger meaning-giving totality as the primary locus of archaeological knowledge. Typology can then be said to serve this overriding quest to resolve the conflict between parts and wholes, as the parts themselves are never sufficient to render the whole but the whole remains elusive without reference to the parts. Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati here make an interesting point about the importance to register the globality of the archaeological record – that is, literally everything encountered in the soil – without making any prior choices as to what supposedly matters and what not. The distinctiveness of the archaeological enterprise, according to them, indeed consists of the circumstance that merely disconnected fragments come to the attention of archaeologists and the only objective data that can be attained, because of this, are about the situated location of fragments in the ground and their relation to other fragments – what they call ‘emplacement’. This, we would add, includes the relationship of fragments with human observers and the employed methods of excavation as observation. As the authors say: “[i]t is in this sense that the fragments are natively digital: they are atoms that do not cohere into a typological whole”. The systematic exploration of how the so recovered fragments may be re-articulated is then essentially the goal of archaeological categorization and typology but these practices can only ever be successful if the whole context of original ‘emplacement’ is carefully taken into consideration. This reconstruction of the fundamental epistemological situation archaeology finds itself in leads the authors to a general rejection of ‘more’ vs. ‘less’ objective or even subjective ordering practices as such qualifications tend to miss the point. What matters is to enable the flexible and scalable confrontation of isolated archaeological fragments, to do experiment with and test different part-whole relations and their possible knowledge contributions. It is no coincidence that the authors insist on a dynamical approach to ordering practices and type-thinking in archaeology here, which in many ways comes often very close to the general conceptual orientation philosopher Stephen C. Pepper (2) has called ‘organicism’ – a preoccupation of resolving the tension between heterogeneous fragments and coherent wholes without losing sight of the specificity of each single fragment. In the view of organicist thinkers, and the authors seem to share this recognition, to take complexity seriously means to centre the dialectics between fragments and wholes in their entirety. This notion is directly reflected in the authors’ interesting definition of ‘big data’ in archaeology as a multi-layered and multi-referential system of organizing the totality of observations of emplacement (the Global record). Based on this broader exposition, Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati make some perceptive and noteworthy observations vis-à-vis the aforementioned emic-etic distinction that has caused so much archaeological confusion and debate (3–6). To begin with, emic and etic designate different systemic logics of organizing observable sameness and difference. Emic systems are closed and foreground the idea of the roster, they recognize only a limited set of types whose identity depends on relative differences. Etic systems, on the other hand, are in principle open (and even open-ended) and rely on the notion of the lexicon; they enlist a principally endless repertoire of traits, types and sub-types (classes and sub-classes may be added to this list of course). Difference in etic systems is moreover defined according to some general standards that appear to eclipse the standards of the system itself. Etic systems therefore tend to advocate supposedly universal principles of how to establish similarity vs. difference, although, in reality, there is substantial debate as to what these principles may be or whether such endeavour is a useful undertaking. In the wild, both etic and emic systems of ordering and categorization are of course encountered in the plural but etic systems deploy external standards of order while emic systems operate via internal standards. An interesting observation by the authors in this context is that archaeological reasoning in relation to sameness and difference is almost never either exclusively etic or exclusively emic. The simple reason is that any grouping of fragments according to technological (means/modes of production) or functional considerations (use-wear, tool design, relation between form and function) based on empirical evidence is typically already infused by emic standards. The classic example from the analysis of archaeological pottery is ware groups, which reference the nexus of technological know-how and concrete practices, and which rely, in a given context, on internal, relative differentiations between the respective observed practices. Yet ignoring these distinctions would sideline significant knowledge on the past. These discussions are refreshing as they may indicate that ordering practices – when considered as an end in themselves – misconstrue the archaeological process as static and so advocate for categories, classes, and types to be carved out before any serious analysis can begin. It could in fact be argued that in doing so, they merely construct a new closed system, then emic by definition. Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati propose an alternative without discarding the intuition that ordering archaeological materials is conditional to the inferential and knowledge-production process: they propose that typologies should be treated as arguments. Moreover, the sort of argument they have in mind is to a lesser extent ‘formal-logical’ but instead emphatically ‘dialogical’ in nature, as such argumentative form helps to combat the inherent static-ness of ordering practices the authors criticize, and so discloses a radically dynamic approach to the undertaking of fragment-whole matching. The organicist inclination to preserve ‘the dignity of fragments’ while working towards their resolution in attendant wholes and sub-wholes further gives rise to the idea that such ‘native digital fragments’ must be brought into systematic conversation with one another, acknowledging the involved complexity. To this end, the authors frame ordering work and typo-praxis as a ‘digital discourse’ and ask what the conditions and possibilities for such discourse are and how it can be facilitated. It is here that they put forward the idea that the webpage may provide an ideal epistemic model system to promote the preservation of emplaced archaeological fragments while simultaneously promoting multistranded and multi-context explorations of fragment coherence and articulation. The website enables unique forms of exploration and engagement with data and new arguments escaping the fixity of the analogue-printed which dominates current archaeological practice. Similar experiences were for example made in the context of Gardin’s ‘logicism’, leading to broadly comparable attempts to overcome the analogue with more dynamic, HTML/web-based forms of data presentation, exploration and discussion (7, 8). As such, Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati table a range of fresh arguments for re-thinking typology beyond and with text at the same time, to enable ‘dynamic reading’ of fragment-whole relationships in an increasingly digital world. Their proposal comes thereby close to what has been termed ‘deep mapping’ in the context of critical cartographies and other spatially-inclined scholarship in the Anglophone world (9, 10). Deep maps seek to transcend the epistemological limitations of 2D-representations of spatiality on traditional maps and introduce different layers of informational depth and heterogeneity, which, similarly to the living digital webpage proposed by the authors, can be continuously extended and revised and which may also greatly promote multidisciplinary and team-based research endeavours. In the same spirit as the authors’ ‘digital discourse’, deep mapping draws attention to the knowledge potential of bringing together the heterogeneous, the etic and the emic, and to pay more attention to ‘multiplanar’ and ‘multilinear’ relationships as well as the associated relations of relations. This proposal to deploy types and typology in general as dynamic arguments is linked to the ambition to contribute to and work on the narrativization of the archaeological record without tacit (and often unconscious) conceptual pre-subscription, countering typologies that remain largely in the abstract and so have contributed to the creeping anonymity of the past.

Bibliography 1. Buccellati, G. and Kelly-Buccellati, M. (2023). The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A website approach to archaeological typology, Zenodo, 7743834, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7743834. 2. Pepper, S C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (Univ. of California Press). 3. Hayden, B. (1984). Are Emic Types Relevant to Archaeology? Ethnohistory 31, 79–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/482057 4. Tostevin, G. B. (2011). An Introduction to the Special Issue: Reduction Sequence, Chaîne Opératoire, and Other Methods: The Epistemologies of Different Approaches to Lithic Analysis. PaleoAnthropology, 293−296. https://www.doi.org/10.4207/PA.2011.ART59 5. Tostevin, G. B. (2013). Seeing lithics: a middle-range theory for testing for cultural transmission in the pleistocene (Oakville, CT: Oxbow Books). 6. Boissinot, P. (2015). Qu’est-ce qu’un fait archéologique? (Éditions EHESS). https://doi.org/10.4000/lectures.19921 7. Gardin, J.-C. and Roux, V. (2004). The Arkeotek Project: a European Network of Knowledge Bases in the Archaeology of Techniques. Archeologia e Calcolatori 15, 25–40. 8. Husi, P. (2022). La céramique médiévale et moderne du bassin de la Loire moyenne, chrono-typologie et transformation des aires culturelles dans la longue durée (6e—17e s.) (FERACF). 9. Bodenhamer, D. J., Corrigan, J. and Harris, T. M. (2015). Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives (Indiana University Press). 10. Gillings, M., Hacigüzeller, P. and Lock, G. R. (2019). Re-mapping archaeology: critical perspectives, alternative mappings (Routledge).

| The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A Website Approach to Archaeological Typology. | Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati | <p>Typology hinges on categorization, and the two main axes of categorization are the roster and the lexicon: the first defines elements from an -emic, and the second from an (e)-tic point of view, i. e., as a closed or an open system, respectivel... |  | Antiquity, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2023-03-17 09:11:46 | View | |

10 Jun 2024

Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times.Artur Ribeiro https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10567441The Postmodern Predicament of Type-Thinking in ArchaeologyRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Gavin Lucas, Miguel John Versluys and Anna S. Beck based on reviews by Gavin Lucas, Miguel John Versluys and Anna S. Beck

“Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times” by A. Ribeiro (1) offers some timely, critical and creative reflections on the manifold struggles of and disappointments in type-thinking and typological approaches in recent archaeological scholarship. Ribeiro insightfully situates what has been identified as a “crisis” in archaeological typo-praxis in the historical conditions of postmodernity and late capitalism themselves. The author thereby attempts what he himself considers “quite hard”, namely “to understand the current Zeitgeist and how it affects how we think and do archaeology” (p. 4). This provides a sort of historical epistemology of the present which can of course only be preliminary and incomplete as it crystallizes, takes shape, and transforms as we write these lines, is available only in fragments and hints, and is generally difficult to talk about and describe as we (the author included) lack critical distance – present-day archaeologists and fellow academics are both enfolded in postmodernity and continue to contribute to its logics and trajectories. Ribeiro’s key argument is provocative as it is interesting: he contends that archaeologists’ difficulties of coming to terms with types and typologies – staple knowledge practices of the discipline ever since – are a symptom of the changing cultural matrix of our times. The diagnosis is multilayered and complex, and Ribeiro at times only scratches the surface of what may be at stake here as he openly admits himself. At the core of his proposal is a shift in attention away from classical questions of epistemological rank, which in archaeology have tended to orbit the contentious issue of the reality of types (see also 2). Instead of foregrounding the question of type-realities – whether types, once identified, can be meaningfully said to exist and to represent something significant in the world – archaeologists are urged to recognize that typo-praxis is culturally saturated in at least two profound ways. First, devising and mobilizing types and typologies is a cultural practice itself – it may indeed have long been a foundational ‘cultural technique’ (Kulturtechnik) (3) of archaeology as a disciplined community-venture of methodical knowledge production. Typo-centric understandings of the archaeological record are quite akin to definition-centric apprehensions of the same as in both cases order, discreteness, and one-to-one correspondence are considered overriding epistemic virtues and credible pointers to a subject-independent “reality”. As such, these practices have a location of their own and they may thus notably conflict with the particularities of alternate and ever-mutating phenomenal realities and historical conditions. Discreteness may for instance lose its paradigmatic status as a descriptor of worldly order, and this is precisely what Ribeiro argues to have happened in the wake of postmodern transformations, influentially said to have deeply reconfigured the relation between the local and the global, at times even superseding such distinctions altogether. When coupled to questions of reality, types, in a similar fashion as definitions, quickly become vehicles to affirm epistemic power and knowledge authority and so help certify certain kinds of realities while supressing others. This is the paradox of modernity: to insist on monolithic understandings of the world while professing radical difference. Second, and for Ribeiro more importantly, typo-praxis is not just subject to cultural variation and thus by implication is plural, it also always has its proper associated cultural milieu in which it exerts some sort of efficacy, i.e. enables action and insight. Ribeiro maintains that this sort of efficacy has become contentious under postmodern conditions and this is because culture, under the gaze of global consumerism, has lost much of its classical significance, and as “hyperculture” (4) developed new logics, significations, and material culture correspondences, essentially “flattening” the highly textured and differentiated world of modernity (p. 6). Some of these new configurations sharply violate the expectations of traditional views of culture. The postmodern situation has in this way effectively emerged as a resistant force proffering much caution and growing scepticism among archaeologists and other academics alike as received ideas about “types” and “cultures” do not seem to work anymore the same way as before. The credibility of different modes of typo-praxis, archaeological or not, in other words, may depend much more on the cultural ecology of lived experience and contemporary diagnosis than is often realized. With Ribeiro, we may say that culture concepts and type concepts are indeed co-constitutive, and what sort of types and typologies archaeologists can persuasively deploy thus also depends greatly on how we construct the link between culture and type, and how (well) we grapple with our own realities and the lessons we draw from them – yet another important reminder of how our own subjectivities figure in such foundational debates (see esp. 5). The crisis of typo-praxis in archaeology, then, is intricately linked to the crisis of modernity, broached by Ribeiro with the labels of postmodernity and late capitalism. Upon reflection, this is not surprising at all since Tylor’s (6) influential definition of culture for example, which is extensively referenced in the paper, was both reflective of and conducive to the project of modernity and its distinctive historical formations such as empire and colonialism. Ribeiro reminds us that questions of justification and credibility, be it in the domain of type-thinking or other epistemic contexts, can never be fully divorced from the contemporary situation, and archaeologists thus need to be vigilant observers of the present, too. Typo-praxis ultimately is motivated by and draws authority from what Foucault (7) has called épistémè, the totality of pertinent parameters forming the historical a priori of understanding or the guiding unconsciousness of subjectivity within a given epoch. The crisis of archaeological typo-praxis, in this view, signifies a calling into question of the historical a priori on which much traditional type-work in archaeology was premised. Archaeologists still have to come to terms with the implications and consequences of this assessment. “Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times” offers a first poignant analysis of some of these challenges of postmodern archaeological type-thinking.

Bibliography 1. Ribeiro, A. (2024). Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times. Zenodo, 10567441, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10567441 2. Hussain, S. T. (2024). The Loss of Typological Innocence: An Archaeology of Archaeological Typo-Praxis. Zenodo, 10567441. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10547264 3. Macho, T. (2013). Second-Order Animals: Cultural Techniques of Identity and Identification. Theory, Culture & Society 30, 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413499189 4. Han, B.-C. (2022). Hyperculture: culture and globalization (Polity Press). 5. Frank, A., Gleiser, M. and Thompson, E. (2024). The blind spot: why science cannot ignore human experience (The MIT Press). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13711.001.0001 6. E. B. Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom (J. Murray). 7. Foucault, M. (2007). The order of things: an archaeology of the human sciences, Repr (Routledge). | Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times. | Artur Ribeiro | <p>Although artifact typologies still play a big role in archaeology, they have certainly lost some repute in recent decades. More than just a collection of items with similar attributes, typologies are a reflection of cultural behaviour and pract... |  | Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2024-01-25 13:40:08 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific RegionChristopher Buckley https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2From Polished Stone Tools to Population Dynamics: Ethnographic Archives as InsightsRecommended by Solène Denis based on reviews by Adrian L. Burke and 1 anonymous reviewerMost archaeological contexts provide objects without organic materials making them quite silent regarding their hafting techniques and use. This is especially true for the polished stone tools that only thanks to a few discoveries in a wet environment, we can obtain some insights regarding their hafting techniques. Use-wear analysis can also be of some support to get a better picture of these artefacts (e.g. Masclans Latorre 2020), whose typology testifies to an important diversity in European Neolithic contexts that sometimes are well-documented from the chaîne opératoire perspective (see De Labriffe and Thirault dir. 2012). The study offered by Chris Buckley (2023) constitutes an important contribution to animating these tools. His work relies on the Asia Pacific region, where he gathered data and mapped more than 300 ethnographic hafted stone and shell tools. This database is available on a webpage https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1D_sC7VUtQRuRcCgc9rROVU7ghrdiVAg&ll=-2.458804534247277%2C154.35254980859378&z=6, providing a short description and pictures of some of the items, completed by Supplementary data. Thanks to this important record of entire objects, the author presents the different possibilities regarding hafting styles, blade orientations and attachment techniques. The combination of these different characteristics led the author to the introduction of a dynamic typology based on the concept of ‘morphospace’. Eight types have been so identified for the Asia Pacific region. The geographical distribution of these types is then presented and questioned, bringing also to the forefront some archaeological findings. An emphasis is made on New Guinea island where documentation is important. We can mention the emblematic work of Anne-Marie and Pierre Pétrequin (1993 and 2020) focused on West Papua, providing one of the most consulted books on stone axes by archaeologists. The worthy explanations tested to understand this repartition mobilize archaeological or linguistic data to hypothesise a three waves model of innovations in link with agricultural practices. A discussion on the correlation between material culture and language highlights in the background the need for interdisciplinary to deal finely with these interactions and linkages as has been effectively demonstrated elsewhere (Hermann and Walworth 2020). To conclude, the convergence between European Neolithic and New Guinea polished stone tools is demonstrated here through ‘morphospace’ comparisons. Thanks to this study, the polished stone tools come alive more than any European archaeological context would allow. The population dynamics investigated through these tools are directly relevant to current scientific issues concerning material culture. This example of convergent evolution is therefore an important key to considering this article as a source of inspiration for the archaeological community. References Buckley C. (2023). Hafted Stone and Shell Tools in the Asia Pacific Region, PsyArXiv, v.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2 De Labriffe A., Thirault E. dir. (2012). Produire des haches au Néolithique, de la matière première à l’abandon, Paris, Société préhistorique française (Séances de la Société préhistorique française, 1). Hermann A., Walworth M. (2020). Approche interdisciplinaire des échanges interculturels et de l’intégration des communautés polynésiennes dans le centre du Vanuatu, Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 151, 239-262. https://doi-org.docelec.u-bordeaux.fr/10.4000/jso.11963 Masclans Latorre A. (2020). Use-wear Analyses of Polished and Bevelled Stone Artefacts during the Sepulcres de Fossa/Pit Burials Horizon (NE Iberia, c. 4000–3400 cal B.C.), Oxford, BAR Publishing (BAR International Series 2972). Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (1993). Écologie d'un outil : la hache de pierre en Irian Jaya (Indonésie), Paris, CNRS Editions. Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (2020). Ecology of a Tool: The ground stone axes of Irian Jaya (Indonesia). Oxbow Books. | Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific Region | Christopher Buckley | <p>Hafted stone tools fell into disuse in the Pacific region in the 19th and 20th centuries. Before this occurred, examples of tools were collected by early travelers, explorers and tourists. These objects, which now reside in ethnographic collect... |  | Asia, Conservation/Museum studies, Lithic technology, Neolithic, Oceania | Solène Denis | 2022-11-09 18:37:08 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, GermanyTharandt, Louise https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7948379Online presentation of the digital reconstruction process of a megalithic tomb : “3Duewelsteene”Recommended by Sophie C. Schmidt and James Allison based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Ronald Visser and Scott Ure based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Ronald Visser and Scott Ure

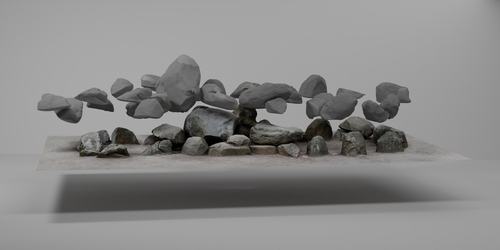

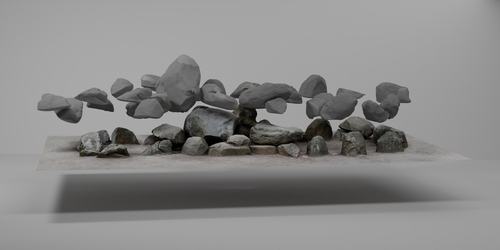

“3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, Germany” (Tharandt 2024) presents several 3-dimensional models of the Düwelsteene monument, along with contextual information about the grave and the process of creating the models. The website (https://3duewelsteene.github.io/) includes English and German versions, making it accessible to a wide audience. The website itself serves as the primary means of presenting the data, rather than as a supplement to a written text. This is an innovative and engaging way to present the research to a wider public. Düwelsteene (“Devil’s Stones”) is a megalithic passage grave from the Funnel Beaker culture, dating to approximately 3300 BC. to 2600 BC. that was excavated in 1932. The website displays three separate 3-dimensional models. They ares shown in the 3D viewer software 3DHOP, which enables viewers to interact with the models in several ways, Annotations on the models display further information. The first model was created by image-based modeling and shows the monument as it appears today. A second model uses historical photographs and excavation data to reconstruct the grave as it appeared prior to the 1932 archaeological excavation. Restoration work following the excavation relocated many of the stones. Pre-1932 photographs collected from residents of the nearby town of Heiden were then used to create a model showing what the tomb looked like before the restoration work. It is commendable that a “certainty view” of the model shows the certainty with which the stones can be put at the reconstructed place. Gaps in the 3D models of stones that were caused by overlap with other stones have been filled with a rough mesh and marked as such, thereby differentiating between known and unknown parts of the stones. The third model is the most imaginative and most interesting. As it shows as the grave as it might have appeared in approximately 3000 B.C., many aspects of this model are necessarily somewhat speculative. There is no direct evidence for exact size and shape of the capstones, the height of the mound, and other details. But enough is known about other similar constructions to allow these details to be inferred with some confidence. Again, care was taken to enable viewers to distinguish between the stones that are still in existence and those that were reconstructed. A video on the home page of the website adds a nice touch. It starts with the model of the Düwelsteene as it currently appears then shows, in reverse order, the changes to the grave, ending with the inferred original state. The 3D reconstructions are convincing and the methods well described. This project follows an open science approach and the FAIR principles, which is commendable and cutting edge in the field of Digital Archaeology. The preprint of the website hosted on zenodo includes all the photos, text, html files, and nine individual 3D model (.ply) files that are combined in the reconstructions exhibited on the website. A “readme.md” file includes details about building the models using CloudCompare and Blender, and modifications to the 3D viewer software (3DHOP) to get the website to improve the display of the reconstructions. We have to note that the link between the reconstructed models and the html page does not work when the files are downloaded from zenodo and opened offline. The html pages open in the browser, and the individual ply files work fine, but the 3D models do not display on the browser page when the html files are opened offline. The online version of the website is working perfectly. The 3Düwelsteene website combines the presentation of archaeological domain knowledge to a lay audience as well as in-depths information on the reconstruction process to make it an interesting contribution for researchers. By providing data and code for the website it also models an Open Science approach, which enables other researchers to re-use these materials. We congratulate the author on a successful reconstruction of the megalithic tomb, an admirable presentation of the archaeological work and the thoughtful outreach to a broad audience. Bibliography | 3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, Germany | Tharandt, Louise | <p>The Düwelsteene near Heiden, Westphalia, is one of the most southern megalithic tombs of the Funnel Beaker culture. In 1932 the Düwelsteene were restored and the appearance of the grave was changed. Even though the megalithic tomb was excavated... |  | Computational archaeology, Mesolithic, Neolithic | Sophie C. Schmidt | 2023-05-21 17:24:22 | View | |

02 Sep 2023

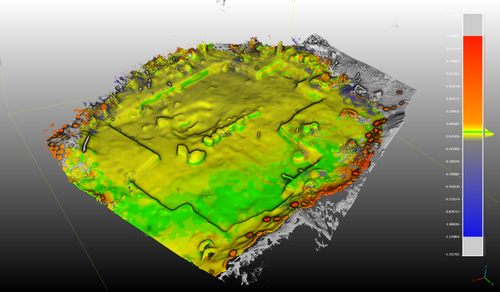

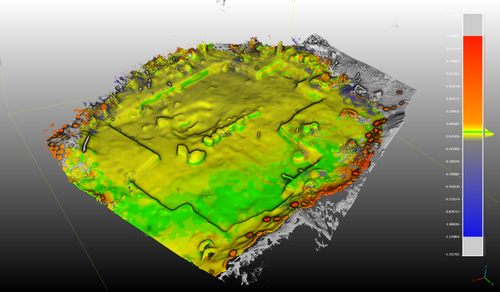

Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation ToolsNikolai Paukkonen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7954534The Potential of Mobile 3D Documentation using Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 ProRecommended by Ying Tung Fung based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and 1 anonymous reviewerI am pleased to recommend the paper titled "Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools" for consideration and publication as a preprint (Paukkonen, 2023). The paper addresses a timely and relevant topic within the field of archaeology and offers valuable insights into the evolving landscape of 3D documentation methods. The advances in technology over the past decade have brought about significant changes in archaeological documentation practices. This paper makes a valuable contribution by discussing the emergence of affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation. Given the constraints that many archaeologists face with limited resources and tight timeframes, the comparison between photogrammetry based on a video captured by a DJI Osmo Pocket gimbal camera and iPhone 12 Pro LiDAR scans is of great significance. The research presented in the paper showcases a practical application of these new technologies in the context of a Finnish Early Modern period archaeological project. By comparing the acquisition processes and evaluating the accuracy, precision, ease of use, and time constraints associated with each method, the authors provide a comprehensive assessment of their potential for archaeological fieldwork. This practical approach is a commendable aspect of the paper, as it not only explores the technical aspects but also considers the practical implications for archaeologists on the ground. Furthermore, the paper appropriately addresses the limitations of these technologies, specifically highlighting their potential inadequacy for projects requiring a higher level of precision, such as Neolithic period excavations. This nuanced perspective adds depth to the discussion and provides a realistic portrayal of the strengths and limitations of the new documentation methods. In conclusion, the paper offers valuable insights into the future of 3D field documentation for archaeologists. The authors' thorough evaluation and practical approach make this study a valuable resource for researchers, practitioners, and professionals in the field. I believe that this paper would be an excellent addition to PCIArchaeology and would contribute significantly to the ongoing dialogue within the archaeological community. References Paukkonen, N. (2023) Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools, Zenodo, 8281263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8281263 | Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools | Nikolai Paukkonen | <p>New affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation has appeared during the last years. Both photogrammetry and laser scanning are becoming affordable for archaeologists, who often work with limited resources and tight time constra... |  | Europe, Post-medieval, Remote sensing | Ying Tung Fung | 2023-05-21 21:32:33 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer