Latest recommendations

| Id | Title▲ | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

05 Jan 2024

The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A Website Approach to Archaeological Typology.Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7743834Roster and Lexicon – A Radical Digital-Dialogical Approach to Questions of Typology and Categorization in ArchaeologyRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and 2 anonymous reviewers

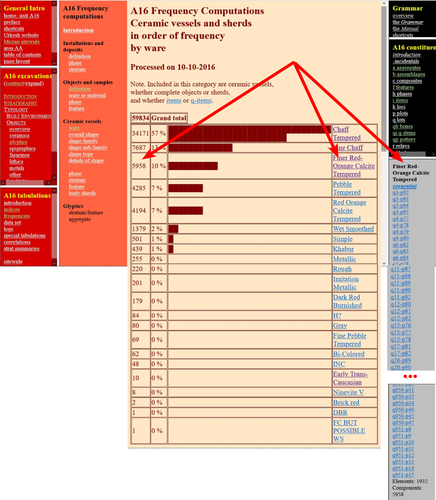

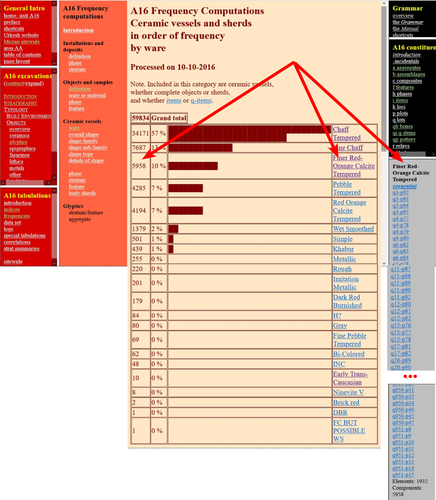

“The density of types and the dignity of the fragment. A website approach to archaeological typology” by G. Buccellati and M. Kelly-Buccellati (1) is a contribution to the rapidly growing literature on digital approaches to archaeological data management, expertly showcasing the significant theoretical and epistemological impetus of such work. The authors offer a conceptually lucid discussion of key concepts in archaeological ordering practices surrounding the longstanding tension between so-called ‘etic’ and ‘emic’ approaches, thereby providing a thorough systematic of how to think through sameness and difference in the context of voluminous digital archaeological data. As a point of departure, the authors reconsider the relationship between archaeological fragments – spatiotemporally bounded artefacts and features – and their larger meaning-giving totality as the primary locus of archaeological knowledge. Typology can then be said to serve this overriding quest to resolve the conflict between parts and wholes, as the parts themselves are never sufficient to render the whole but the whole remains elusive without reference to the parts. Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati here make an interesting point about the importance to register the globality of the archaeological record – that is, literally everything encountered in the soil – without making any prior choices as to what supposedly matters and what not. The distinctiveness of the archaeological enterprise, according to them, indeed consists of the circumstance that merely disconnected fragments come to the attention of archaeologists and the only objective data that can be attained, because of this, are about the situated location of fragments in the ground and their relation to other fragments – what they call ‘emplacement’. This, we would add, includes the relationship of fragments with human observers and the employed methods of excavation as observation. As the authors say: “[i]t is in this sense that the fragments are natively digital: they are atoms that do not cohere into a typological whole”. The systematic exploration of how the so recovered fragments may be re-articulated is then essentially the goal of archaeological categorization and typology but these practices can only ever be successful if the whole context of original ‘emplacement’ is carefully taken into consideration. This reconstruction of the fundamental epistemological situation archaeology finds itself in leads the authors to a general rejection of ‘more’ vs. ‘less’ objective or even subjective ordering practices as such qualifications tend to miss the point. What matters is to enable the flexible and scalable confrontation of isolated archaeological fragments, to do experiment with and test different part-whole relations and their possible knowledge contributions. It is no coincidence that the authors insist on a dynamical approach to ordering practices and type-thinking in archaeology here, which in many ways comes often very close to the general conceptual orientation philosopher Stephen C. Pepper (2) has called ‘organicism’ – a preoccupation of resolving the tension between heterogeneous fragments and coherent wholes without losing sight of the specificity of each single fragment. In the view of organicist thinkers, and the authors seem to share this recognition, to take complexity seriously means to centre the dialectics between fragments and wholes in their entirety. This notion is directly reflected in the authors’ interesting definition of ‘big data’ in archaeology as a multi-layered and multi-referential system of organizing the totality of observations of emplacement (the Global record). Based on this broader exposition, Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati make some perceptive and noteworthy observations vis-à-vis the aforementioned emic-etic distinction that has caused so much archaeological confusion and debate (3–6). To begin with, emic and etic designate different systemic logics of organizing observable sameness and difference. Emic systems are closed and foreground the idea of the roster, they recognize only a limited set of types whose identity depends on relative differences. Etic systems, on the other hand, are in principle open (and even open-ended) and rely on the notion of the lexicon; they enlist a principally endless repertoire of traits, types and sub-types (classes and sub-classes may be added to this list of course). Difference in etic systems is moreover defined according to some general standards that appear to eclipse the standards of the system itself. Etic systems therefore tend to advocate supposedly universal principles of how to establish similarity vs. difference, although, in reality, there is substantial debate as to what these principles may be or whether such endeavour is a useful undertaking. In the wild, both etic and emic systems of ordering and categorization are of course encountered in the plural but etic systems deploy external standards of order while emic systems operate via internal standards. An interesting observation by the authors in this context is that archaeological reasoning in relation to sameness and difference is almost never either exclusively etic or exclusively emic. The simple reason is that any grouping of fragments according to technological (means/modes of production) or functional considerations (use-wear, tool design, relation between form and function) based on empirical evidence is typically already infused by emic standards. The classic example from the analysis of archaeological pottery is ware groups, which reference the nexus of technological know-how and concrete practices, and which rely, in a given context, on internal, relative differentiations between the respective observed practices. Yet ignoring these distinctions would sideline significant knowledge on the past. These discussions are refreshing as they may indicate that ordering practices – when considered as an end in themselves – misconstrue the archaeological process as static and so advocate for categories, classes, and types to be carved out before any serious analysis can begin. It could in fact be argued that in doing so, they merely construct a new closed system, then emic by definition. Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati propose an alternative without discarding the intuition that ordering archaeological materials is conditional to the inferential and knowledge-production process: they propose that typologies should be treated as arguments. Moreover, the sort of argument they have in mind is to a lesser extent ‘formal-logical’ but instead emphatically ‘dialogical’ in nature, as such argumentative form helps to combat the inherent static-ness of ordering practices the authors criticize, and so discloses a radically dynamic approach to the undertaking of fragment-whole matching. The organicist inclination to preserve ‘the dignity of fragments’ while working towards their resolution in attendant wholes and sub-wholes further gives rise to the idea that such ‘native digital fragments’ must be brought into systematic conversation with one another, acknowledging the involved complexity. To this end, the authors frame ordering work and typo-praxis as a ‘digital discourse’ and ask what the conditions and possibilities for such discourse are and how it can be facilitated. It is here that they put forward the idea that the webpage may provide an ideal epistemic model system to promote the preservation of emplaced archaeological fragments while simultaneously promoting multistranded and multi-context explorations of fragment coherence and articulation. The website enables unique forms of exploration and engagement with data and new arguments escaping the fixity of the analogue-printed which dominates current archaeological practice. Similar experiences were for example made in the context of Gardin’s ‘logicism’, leading to broadly comparable attempts to overcome the analogue with more dynamic, HTML/web-based forms of data presentation, exploration and discussion (7, 8). As such, Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati table a range of fresh arguments for re-thinking typology beyond and with text at the same time, to enable ‘dynamic reading’ of fragment-whole relationships in an increasingly digital world. Their proposal comes thereby close to what has been termed ‘deep mapping’ in the context of critical cartographies and other spatially-inclined scholarship in the Anglophone world (9, 10). Deep maps seek to transcend the epistemological limitations of 2D-representations of spatiality on traditional maps and introduce different layers of informational depth and heterogeneity, which, similarly to the living digital webpage proposed by the authors, can be continuously extended and revised and which may also greatly promote multidisciplinary and team-based research endeavours. In the same spirit as the authors’ ‘digital discourse’, deep mapping draws attention to the knowledge potential of bringing together the heterogeneous, the etic and the emic, and to pay more attention to ‘multiplanar’ and ‘multilinear’ relationships as well as the associated relations of relations. This proposal to deploy types and typology in general as dynamic arguments is linked to the ambition to contribute to and work on the narrativization of the archaeological record without tacit (and often unconscious) conceptual pre-subscription, countering typologies that remain largely in the abstract and so have contributed to the creeping anonymity of the past.

Bibliography 1. Buccellati, G. and Kelly-Buccellati, M. (2023). The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A website approach to archaeological typology, Zenodo, 7743834, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7743834. 2. Pepper, S C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (Univ. of California Press). 3. Hayden, B. (1984). Are Emic Types Relevant to Archaeology? Ethnohistory 31, 79–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/482057 4. Tostevin, G. B. (2011). An Introduction to the Special Issue: Reduction Sequence, Chaîne Opératoire, and Other Methods: The Epistemologies of Different Approaches to Lithic Analysis. PaleoAnthropology, 293−296. https://www.doi.org/10.4207/PA.2011.ART59 5. Tostevin, G. B. (2013). Seeing lithics: a middle-range theory for testing for cultural transmission in the pleistocene (Oakville, CT: Oxbow Books). 6. Boissinot, P. (2015). Qu’est-ce qu’un fait archéologique? (Éditions EHESS). https://doi.org/10.4000/lectures.19921 7. Gardin, J.-C. and Roux, V. (2004). The Arkeotek Project: a European Network of Knowledge Bases in the Archaeology of Techniques. Archeologia e Calcolatori 15, 25–40. 8. Husi, P. (2022). La céramique médiévale et moderne du bassin de la Loire moyenne, chrono-typologie et transformation des aires culturelles dans la longue durée (6e—17e s.) (FERACF). 9. Bodenhamer, D. J., Corrigan, J. and Harris, T. M. (2015). Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives (Indiana University Press). 10. Gillings, M., Hacigüzeller, P. and Lock, G. R. (2019). Re-mapping archaeology: critical perspectives, alternative mappings (Routledge).

| The Density of Types and the Dignity of the Fragment. A Website Approach to Archaeological Typology. | Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati | <p>Typology hinges on categorization, and the two main axes of categorization are the roster and the lexicon: the first defines elements from an -emic, and the second from an (e)-tic point of view, i. e., as a closed or an open system, respectivel... |  | Antiquity, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2023-03-17 09:11:46 | View | |

03 Nov 2023

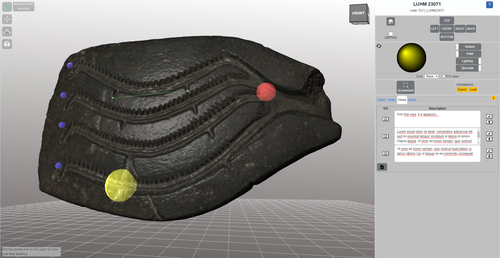

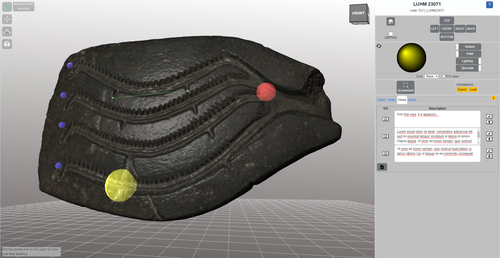

The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep InteractionMarco Callieri, Åsa Berggren, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Paola Derudas, Domenica Dininno, Fredrik Ekengren, Giuseppe Naponiello https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10067103A comparative teaching and learning tool for 3D data: Dynamic CollectionsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Louise Tharandt based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Louise Tharandt

The paper (Callieri, M. et al. 2023) describes the “Dynamic Collections” project, an online platform initially created to showcase digital archaeological collections of Lund University. During a phase of testing by department members, new functionalities and artefacts were added resulting in an interactive platform adapted to university-level teaching and learning. The paper introduces into the topic and related works after which it starts to explain the project itself. The idea is to resemble the possibilities of interaction of non-digital collections in an online platform. Besides the objects themselves, the online platform offers annotations, measurement and other interactive tools based on the already known 3DHOP framework. With the possibility to create custom online collections a collaborative working/teaching environment can be created. The already wide-spread use of the 3DHOP framework enabled the authors to develop some functionalities that could be used in the “Dynamic Collections” project. Also, current and future plans of the project are discussed and will include multiple 3D models for one object or permanent identifiers, which are both important additions to the system. The paper then continues to explain some of its further planned improvements, like comparisons and support for teaching, which will make the tool an important asset for future university-level education. The paper in general is well-written and informative and introduces into the interactive tool, that is already available and working. It is very positive, that the authors rely on up-to-date methodologies in creating 3D online repositories and are in fact improving them by testing the tool in a teaching environment. They mention several times the alignment with upcoming EU efforts related to the European Collaborative Cloud for Cultural Heritage (ECCCH), which is anticipatory and far-sighted and adds to the longevity of the project. Comments of the reviewers were reasonably implemented and led to a clearer and more concise paper. I am very confident that this tool will find good use in heritage research and presentation as well as in university-level teaching and learning. Although the authors never answer the introductory question explicitly (What characteristics should a virtual environment have in order to trigger dynamic interaction?), the paper gives the implicit answer by showing what the "Dynamic Collections" project has achieved and is able to achieve in the future. BibliographyCallieri, M., Berggren, Å., Dell'Unto, N., Derudas, P., Dininno, D., Ekengren, F., and Naponiello, G. (2023). The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep Interaction, Zenodo, 10067103, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10067103 | The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep Interaction | Marco Callieri, Åsa Berggren, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Paola Derudas, Domenica Dininno, Fredrik Ekengren, Giuseppe Naponiello | <p>The Dynamic Collections project is an ongoing initiative pursued by the Visual Computing Lab ISTI-CNR in Italy and the Lund University Digital Archaeology Laboratory-DARKLab, Sweden. The aim of this project is to explore the possibilities offer... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-31 15:05:32 | View | |

26 Sep 2022

The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspectiveSolange Rigaud, John O’Hara, Laurent Charles, Elena Man-Estier, Patrick Paillet https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/z7pqgCaching up with the study of the procurement of symbolic raw materials in the Upper PalaeolithicRecommended by Beatrice Demarchi based on reviews by Begoña Soler Mayor , Catherine Dupont and Lawrence StrausThe manuscript "The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective" by Solange Rigaud and colleagues (Rigaud et al. 2022) is a perfect demonstration that appropriate scientific methodologies can be used effectively in order to enhance the historical value of findings from “old” collections, despite the lack of secure stratigraphic and contextual data. The shell assemblage (n = 377) investigated here (from Rochereil, Dordogne) had been excavated during the first half of the 20th century (Jude 1960) and reported in 1993 (Taborin 1993), but only this recent analysis revealed that it was composed of largely unmodified mollusc shells, most of allochthonous origin. Rigaud et al. interpret this finding as the raw materials used to produce personal ornaments. This is especially significant, because the focus of research has been on the manufacture, use and exchange of personal ornaments in prehistory, much less so on the procurement of the raw materials. As such, the manuscript adds substantially to the growing literature on Magdalenian social networks. The authors carried out detailed taxonomic analysis based on morphological and morphometric characteristics and identified at least nine different species, including Dentalium sp., Ocenebra erinaceus, Tritia reticulata and T. gibbosula, as well as some bivalve specimens (Mytilus, Glycymeris, Spondylus, Pecten). Most of the species are commonly found in personal ornament assemblages from the Magdalenian, reflecting intentional selection (also shown by the size sorting of some of the taxa), and cultural continuity. However, microscopic examinations revealed securely-identified anthropogenic modifications on a very limited number of specimens: one Glycymeris valve (used as an ochre container), one Cardiidae valve (presence of a groove), one perforated Tritia gibbosula and two perforated Tritia reticulata bearing striations. The authors interpret this combination of anthropogenic vs natural “signals” as signifying that the assemblage represents raw material selected and stored for further processing. Assessing the provenance and age of the shells is therefore paramount: the shells found at Rochereil belong to species that can be found on both the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. Assuming that molluscan taxa distribution in the past is comparable to that for the present day, this implies the exploitation of two catchment areas and long-distance transportation to the site: taking sea-level changes into account, during the Magdalenian the Mediterranean used to lie at a distance of 350 km from Rochereil, and the Atlantic was not significantly closer (~200 km). Importantly, exploitation of fossil shells cannot be discounted on the basis of the data presented here; direct dating of some of the specimens (e.g. by radiocarbon, or amino acid racemisation geochronology) would be beneficial to clarify this issue and in general to improve chronological control on the accumulation of shells. Nonetheless, the authors argue that the closest fossil deposits also lie more than 200 km away from the site, thus the material is allochthonous in origin. In synthesis, the Rochereil assemblage represents an important step towards a better understanding of the procurement chain and of the production of ornaments during the European Upper Palaeolithic. References Jude, P. E. (1960). La grotte de Rocherreil: station magdalénienne et azilienne, Masson. Rigaud, S., O'Hara, J., Charles, L., Man-Estier, E. and Paillet, P. (2022) The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective. SocArXiv, z7pqg, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/z7pqg Taborin, Y. (1993). La parure en coquillage au Paléolithique, CNRS éditions. | The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective | Solange Rigaud, John O’Hara, Laurent Charles, Elena Man-Estier, Patrick Paillet | <p>Personal ornaments manufactured on marine and fossil shell are a significant element of Upper Palaeolithic symbolic material culture, and are often found at considerable distances from Pleistocene coastlines or relevant fossil deposits. Here, w... |  | Europe, Symbolic behaviours, Upper Palaeolithic | Beatrice Demarchi | 2022-04-23 19:20:02 | View | |

24 Jun 2021

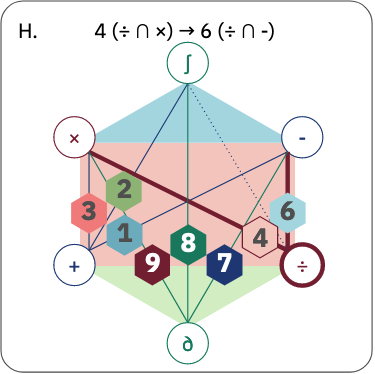

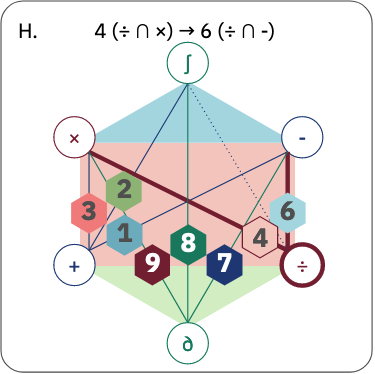

The strength of parthood ties. Modelling spatial units and fragmented objects with the TSAR method – Topological Study of Archaeological RefittingSébastien Plutniak https://osf.io/q2e69A practical computational approach to stratigraphic analysis using conjoinable material culture.Recommended by Hector A. Orengo based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper by Plutniak [1] presents a new method that uses refitting to help interpret stratigraphy using the topological distribution of conjoinable material culture. This new method opens up new avenues to the archaeological use of network analysis but also to assess the integrity of interpreted excavation layers. Beyond its evident applicability to standard excavation practice, the paper presents a series of characteristics that exemplify archaeological publication best practices and, as someone more versed in computational than in refitting studies I would like to comment upon. It was no easy task to find adequate reviewers for this paper as it combines techniques and expertise that are not commonly found together in individual researchers. However, Plutniak, with help from three reviewers, particularly M. Peeples, a leading figure in archaeological applications of network science, makes a considerable effort to be accessible to non-specialist archaeologists. The core Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting (TSAR) method is freely accessible as the R package archeofrag, which is available at the Comprehensive R Archive Network (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=archeofrag) that can be applied without the need to understand all its mathematical, graph theory and coding aspects. Beside these, an online interface including test data has been provided (https://analytics.huma-num.fr/Sebastien.Plutniak/archeofrag/), which aims to ease access to the method to those archaeologists inexperienced with R. Finally, supplementary material showing how to use the package and evaluating its potential through excellent examples is provided as both pdf and Rmw (Sweave) files. This is an important companion for the paper as it allows a better understanding of the methods presented in the paper and its practical application. The author shows particular care in testing the potential and capabilities of the method. For example, a function is provided “frag.observer.failure” to test the robustness of the edge count method against the TSAR method, which is able to prove that TSAR can deal well with incomplete information. As a further step in this direction both simulated and real field-acquired data are used to test the method which further proves that archeofrag is not only able to quantitatively assess the mixture of excavated layers but to propose meaningful alternatives, which no doubt will add an increased methodological consistency and thoroughness to previous quantitative approaches to material refitting work, even when dealing with very complex stratigraphies. All in all, this paper makes an important contribution to core archaeological practice through the use of innovative, reproducible and accessible computational methods. I fully endorse it for the conscious and solid methods it presents but also for its adherence to open publication practices. I hope that it can become of standard use in the reconstruction of excavated stratigraphical layers through conjoinable material culture.

[1] Plutniak, S. 2021. The Strength of Parthood Ties. Modelling Spatial Units and Fragmented Objects with the TSAR Method – Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting. OSF Preprints, q2e69, ver. 3 Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/q2e69. | The strength of parthood ties. Modelling spatial units and fragmented objects with the TSAR method – Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting | Sébastien Plutniak | <p>Refitting and conjoinable pieces have long been used in archaeology to assess the consistency of discrete spatial units, such as layers, and to evaluate disturbance and post-depositional processes. The majority of current methods, despite their... | Computational archaeology, Taphonomy | Hector A. Orengo | 2021-01-14 18:31:01 | View | ||

22 Apr 2024

The transformation of an archaeological community and its resulting representations in the context of the co-development of open Archaeological Information SystemsEric Lacombe, Dominik Lukas, Sébastien Durost https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309732Exploring The Role of Archaeological Information Systems in Improving Data Management and InteroperabilityRecommended by James Stuart Taylor based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In response to the feedback provided by the reviewers, the authors have undertaken a comprehensive revision of the manuscript [1]. These revisions have specifically targeted the primary concerns raised regarding the clarity and structure of the argument concerning the transformative impact of Archaeological Information Systems (AIS) on archaeological practices. In my view the revised manuscript now more clearly articulates the distinction between internal and external interoperability and emphasizes the critical importance of integrating contextual information with archaeological data. This approach directly addresses the previously identified need for enhanced traceability and usability of archaeological data, ensuring that the manuscript's contributions to the field are both clear and impactful. Moreover, the application of the proposed model at the Bibracte site is illustrated with greater clarity, serving as a concrete example of how the challenges associated with documentation and data management can be effectively addressed through the methodologies proposed in the paper. This practical demonstration enriches the manuscript, providing readers with a much clearer understanding of the model's applicability and benefits in real-world archaeological practice. The authors have also made significant efforts to refine the overall structure and coherence of the manuscript. By making complex concepts more accessible and ensuring a cohesive narrative flow throughout, the manuscript now offers a more engaging and comprehensible read. This has been achieved through careful rephrasing and restructuring of sections, particularly those relating to the T!O model's application and the conclusion, thereby enhancing reader engagement and comprehension. Alongside these structural and conceptual clarifications, explicit discussion of potential areas for future research, not only acknowledges the limitations of the current study but also highlights the significant potential for digital technologies to contribute to archaeological methodology and knowledge production. As such, the manuscript opens up new avenues for exploration and invites further scholarly engagement with the topics it addresses. I believe, these revisions address the earlier feedback quite comprehensively, presenting a robust and compelling argument for the adoption of collaborative and technologically informed approaches in the field of archaeology. The manuscript now stands as a strong example of the critical role AIS could/should play in transforming archaeological practices, offering valuable insights into how these kinds of systems might enhance the management, accessibility, and understanding of archaeological data. Through this revised submission, the authors have significantly strengthened their contribution to the ongoing discourse on digital archaeology, demonstrating the practical and theoretical implications of their work for the broader archaeological community. I am happy, therefore to recommend this paper for acceptence. Reference [1] Lacombe, E., Lukas, D. and Durost, S. (2024). The transformation of an archaeological community and its resulting representations in the context of the co-development of open Archaeological Information Systems. Zenodo, 8309732, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309732

| The transformation of an archaeological community and its resulting representations in the context of the co-development of open Archaeological Information Systems | Eric Lacombe, Dominik Lukas, Sébastien Durost | <p>The adoption of Archaeological Information Systems (AIS) evolves according to multiple factors, both human and technical, as well as endogenous and exogenous. In consequence the ever increasing scope of digital tools, which allow for the organi... |  | Computational archaeology, Europe, Protohistory, Theoretical archaeology | James Stuart Taylor | 2023-09-01 18:58:26 | View | |

28 May 2020

TIPZOO: a Touchscreen Interface for Palaeolithic Zooarchaeology. Towards making data entry and analysis easier, faster, and more reliableEmmanuel Discamps https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/aew5cA new software to improve standardization and quality of data in zooarchaeologyRecommended by Florent Rivals based on reviews by Delphine Vettese and Argant Thierry based on reviews by Delphine Vettese and Argant Thierry

Standardization and quality of data collection are identified as challenges for the future in zooarchaeology [1]. These issues were already identified in the early 1970s when the International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ) recommended to “standardize measurements and data in publications”. In the recent years, there is strong recommendations by publishers and grant to follow the FAIR Principle i.e. to “improve the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reuse of digital assets” [2]. As zooarchaeologists, we should make our methods more clear and replicable by other researchers to produce comparable datasets. In this paper the authors make a significant step in proposing a tool to replace traditional data recording softwares. The problems related to data recording are clearly identified and discussed. All the features offered by TIPZOO allow to standardize the data, to reduce the errors when entering the data, to save time with auto-filling entries. The coding system used in TIPZOO is based on variables taken from the most used and updated literature in zooarchaeology. Its connections with various R packages allow to directly export the data and to transform the raw data to produce summary tables, graphs and basic statistics. Finally, the advantage of this tool is that it can be improved, debugged, or implemented at any time. TIPZOO provides a standardized system to compile and share large and consistent datasets that will allow comparison among assemblages at a large scale, and for this reason, I have recommended the work for PCI Archaeology. References [1] Steele, T.E. (2015). The contributions of animal bones from archaeological sites: the past and future of zooarchaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 56, 168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2015.02.036 | TIPZOO: a Touchscreen Interface for Palaeolithic Zooarchaeology. Towards making data entry and analysis easier, faster, and more reliable | Emmanuel Discamps | <p>Zooarchaeological studies of fossil bone collections are often conducted using simple spreadsheet programs for data recording and analysis. After quickly summarizing the limitations of such an approach, we present a new software solution, TIPZO... |  | Spatial analysis, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Florent Rivals | 2020-04-16 13:27:00 | View | |

05 Jul 2023

Tool types and the establishment of the Late Palaeolithic (Later Stone Age) cultural taxonomic system in the Nile ValleyAlice Leplongeon https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8115202Cultural taxonomic systems and the Late Palaeolithic/Later Stone Age prehistory of the Nile Valley – a critical reviewRecommended by Felix Riede, Sébastien Plutniak and Shumon Tobias Hussain and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Giuseppina Mutri and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Giuseppina Mutri and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper entitled “Tool types and the establishment of the Late Palaeolithic (Later Stone Age) cultural taxonomic system in the Nile Valley” submitted by A. Leplongeon offers a review of the many cultural taxonomic in use for the prehistory – especially the Late Palaeolithic/Late Stone Age – of the Nile Valley (Leplongeon 2023). This paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology and taxonomy in archaeology. Issues of cultural taxonomy have recently risen to the forefront of archaeological debate (Reynolds and Riede 2019; Ivanovaitė et al. 2020; Lyman 2021). Archaeological systematics, most notably typology, have roots in the research history of a particular region and period (e.g. Plutniak 2022); commonly, different scholars employ different and at times incommensurable systems, often leading to a lack of clarity and inter-regional interoperability. African prehistory is not exempt from this debate (e.g. Wilkins 2020) and, in fact, such a situation is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in the iconic Nile Valley. The Nile Valley is marked by a complex colonial history and long-standing archaeological interest from a range of national and international actors. It is also a vital corridor for understanding human dispersals out of and into Africa, and along the North African coastal zone. As Leplongeon usefully reviews, early researchers have, as elsewhere, proposed a variety of archaeological cultures, the legacies of which still weigh in on contemporary discussions. In the Nile Valley, these are the Kubbaniyan (23.5-19.3 ka cal. BP), the Halfan (24-19 ka cal. BP), the Qadan (20.2-12 ka cal BP), the Afian (16.8-14 ka cal. BP) and the Isnan (16.6-13.2 ka cal. BP) but their temporal and spatial signatures remain in part poorly constrained, or their epistemic status debated. Leplongeon’s critical and timely chronicle of this debate highlights in particular the vital contributions of the many female prehistorians who have worked in the region – Angela Close (e.g. 1978; 1977) and Maxine Kleindienst (e.g. 2006) to name just a few of the more recent ones – and whose earlier work had already addressed, if not even solved many of the pressing cultural taxonomic issues that beleaguer the Late Palaeolithic/Later Stone Age record of this region. Leplongeon and colleagues (Leplongeon et al. 2020; Mesfin et al. 2020) have contributed themselves substantially to new cultural taxonomic research in the wider region, showing how novel quantitative methods coupled with research-historical acumen can flag up and overcome the shortcomings of previous systematics. Yet, as Leplongeon also notes, the cultural taxonomic framework for the Nile Valley specifically has proven rather robust and does seem to serve its purpose as a broad chronological shorthand well. By the same token, she urges due caution when it comes to interpreting these lithic-based taxonomic units in terms of past social groups. Cultural systematics are essential for such interpretations, but age-old frameworks are often not fit for this purpose. New work by Leplongeon is likely to not only continue the long tradition of female prehistorians working in the Nile Valley but also provides an epistemologically and empirically more robust platform for understanding the social and ecological dynamics of Late Palaeolithic/Later Stone Age communities there.

Bibliography Close, Angela E. 1977. The Identification of Style in Lithic Artefacts from North East Africa. Mémoires de l’Institut d’Égypte 61. Cairo: Geological Survey of Egypt. Close, Angela E. 1978. “The Identification of Style in Lithic Artefacts.” World Archaeology 10 (2): 223–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1978.9979732 Ivanovaitė, Livija, Serwatka, Kamil, Steven Hoggard, Christian, Sauer, Florian and Riede, Felix. 2020. “All These Fantastic Cultures? Research History and Regionalization in the Late Palaeolithic Tanged Point Cultures of Eastern Europe.” European Journal of Archaeology 23 (2): 162–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2019.59 Kleindienst, M. R. 2006. “On Naming Things: Behavioral Changes in the Later Middle to Earlier Late Pleistocene, Viewed from the Eastern Sahara.” In Transitions Before the Transition. Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age, edited by E. Hovers and Steven L. Kuhn, 13–28. New York, NY: Springer. Leplongeon, Alice. 2023. “Tool Types and the Establishment of the Late Palaeolithic (Later Stone Age) Cultural Taxonomic System in the Nile Valley.” https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8115202 Leplongeon, Alice, Ménard, Clément, Bonhomme, Vincent and Bortolini, Eugenio. 2020. “Backed Pieces and Their Variability in the Later Stone Age of the Horn of Africa.” African Archaeological Review 37 (3): 437–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-020-09401-x Lyman, R. Lee. 2021. “On the Importance of Systematics to Archaeological Research: The Covariation of Typological Diversity and Morphological Disparity.” Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 4 (1): 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00077-6 Mesfin, Isis, Leplongeon, Alice, Pleurdeau, David, and Borel, Antony. 2020. “Using Morphometrics to Reappraise Old Collections: The Study Case of the Congo Basin Middle Stone Age Bifacial Industry.” Journal of Lithic Studies 7 (1): 1–38. https://doi.org/10.2218/jls.4329 Plutniak, Sébastien. 2022. “What Makes the Identity of a Scientific Method? A History of the ‘Structural and Analytical Typology’ in the Growth of Evolutionary and Digital Archaeology in Southwestern Europe (1950s–2000s).” Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 5 (1): 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-022-00119-7 Reynolds, Natasha, and Riede, Felix. 2019. “House of Cards: Cultural Taxonomy and the Study of the European Upper Palaeolithic.” Antiquity 93 (371): 1350–58. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.49 Wilkins, Jayne. 2020. “Is It Time to Retire NASTIES in Southern Africa? Moving Beyond the Culture-Historical Framework for Middle Stone Age Lithic Assemblage Variability.” Lithic Technology 45 (4): 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/01977261.2020.1802848 | Tool types and the establishment of the Late Palaeolithic (Later Stone Age) cultural taxonomic system in the Nile Valley | Alice Leplongeon | <p>Research on the prehistory of the Nile Valley has a long history dating back to the late 19th century. But it is only between the 1960s and 1980s, that numerous cultural entities were defined based on tool and core typologies; this habit stoppe... |  | Africa, Lithic technology, Upper Palaeolithic | Felix Riede | 2023-03-08 19:25:28 | View | |

02 Sep 2023

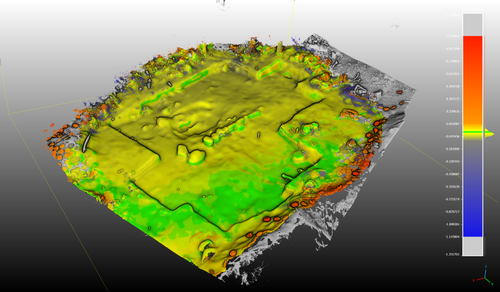

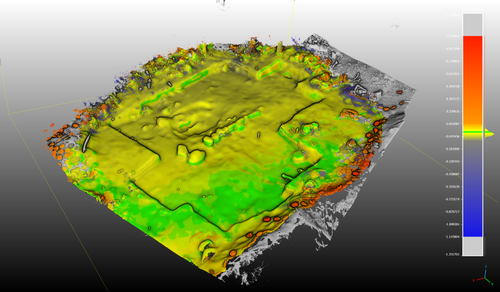

Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation ToolsNikolai Paukkonen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7954534The Potential of Mobile 3D Documentation using Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 ProRecommended by Ying Tung Fung based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and 1 anonymous reviewerI am pleased to recommend the paper titled "Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools" for consideration and publication as a preprint (Paukkonen, 2023). The paper addresses a timely and relevant topic within the field of archaeology and offers valuable insights into the evolving landscape of 3D documentation methods. The advances in technology over the past decade have brought about significant changes in archaeological documentation practices. This paper makes a valuable contribution by discussing the emergence of affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation. Given the constraints that many archaeologists face with limited resources and tight timeframes, the comparison between photogrammetry based on a video captured by a DJI Osmo Pocket gimbal camera and iPhone 12 Pro LiDAR scans is of great significance. The research presented in the paper showcases a practical application of these new technologies in the context of a Finnish Early Modern period archaeological project. By comparing the acquisition processes and evaluating the accuracy, precision, ease of use, and time constraints associated with each method, the authors provide a comprehensive assessment of their potential for archaeological fieldwork. This practical approach is a commendable aspect of the paper, as it not only explores the technical aspects but also considers the practical implications for archaeologists on the ground. Furthermore, the paper appropriately addresses the limitations of these technologies, specifically highlighting their potential inadequacy for projects requiring a higher level of precision, such as Neolithic period excavations. This nuanced perspective adds depth to the discussion and provides a realistic portrayal of the strengths and limitations of the new documentation methods. In conclusion, the paper offers valuable insights into the future of 3D field documentation for archaeologists. The authors' thorough evaluation and practical approach make this study a valuable resource for researchers, practitioners, and professionals in the field. I believe that this paper would be an excellent addition to PCIArchaeology and would contribute significantly to the ongoing dialogue within the archaeological community. References Paukkonen, N. (2023) Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools, Zenodo, 8281263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8281263 | Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools | Nikolai Paukkonen | <p>New affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation has appeared during the last years. Both photogrammetry and laser scanning are becoming affordable for archaeologists, who often work with limited resources and tight time constra... |  | Europe, Post-medieval, Remote sensing | Ying Tung Fung | 2023-05-21 21:32:33 | View | |

11 Oct 2023

Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill ProjectSamanta Mariotti https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563Gamification of an archaeological park: The Living Hill Project as work-in-progressRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer

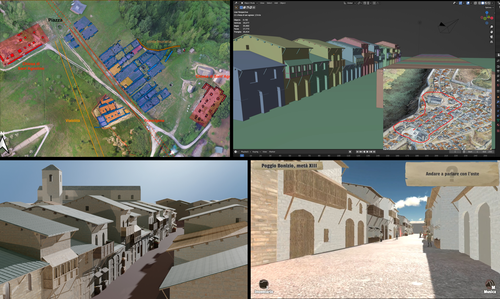

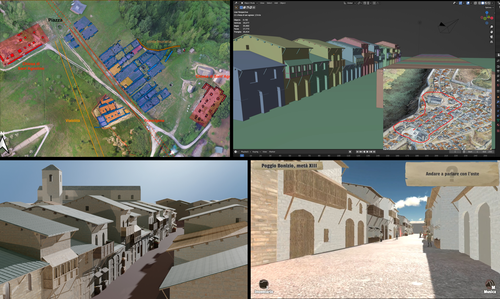

This paper (2023) describes The Living Hill project dedicated to the archaeological park and fortress of Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi, Italy. The project is a collaboration between the Poggibonsi excavation and Entertainment Games App, Ltd. From the start, the project focused on the question of the intended audience rather than on the used technology. It was therefore planned to involve the audience in the creation of the game itself, which was not possible after all due to the covid pandemic. Nevertheless, the game aimed towards a visit experience as close as possible to reality to offer an educational tool through the video game, as it offers more periods than the medieval period showcased in the archaeological park itself. The game mechanics differ from a walking simulator, or a virtual tour and the player is tasked with returning three lost objects in the virtual game. While the medieval level was based on a 3D scan of the archaeological park, the other two levels were reconstructed based on archaeological material. Currently, only a PC version is working, but the team works on a mobile version as well and teased the possibility that the source code will be made available open source. Lastly, the team also evaluated the game and its perception through surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Although the surveys were only based on 21 persons, the results came back positive overall. The paper is well-written and follows a consistent structure. The authors clearly define the goals and setting of the project and how they developed and evaluated the game. Although it has be criticized that the game is not playable yet and the size of the questionnaire is too low, the authors clearly replied to the reviews and clarified the situation on both matters. They also attended to nearly all of the reviewers demands and answered them concisely in their response. In my personal opinion, I can fully recommend this paper for publication. For future works, it is recommended that the authors enlarge their audience for the quesstionaire in order to get more representative results. It it also recommended to make the game available as soon as possible also outside of the archaeological park. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their concise and constructive criticism to this paper as well as for their time. References Mariotti, Samanta. (2023) Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project, Zenodo, 8302563, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563 | Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of *The Living Hill* Project | Samanta Mariotti | <p>Video games are now recognised as a valuable tool for disseminating and enhancing archaeological heritage. In Italy, the recent institutionalisation of Public Archaeology programs and incentives for digital innovation has resulted in a prolifer... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Europe, Medieval, Post-medieval | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-30 20:25:32 | View | |

05 Jan 2024

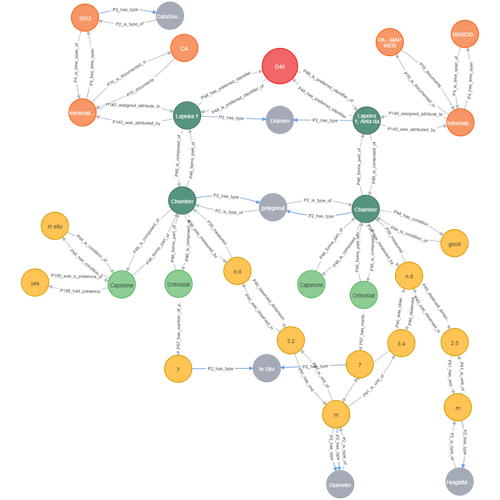

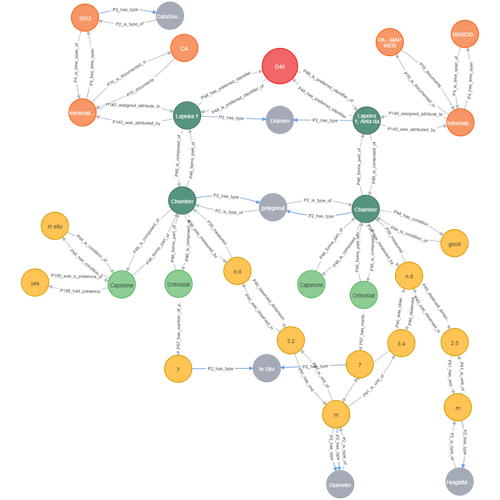

Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graphAriele Câmara, Ana de Almeida, João Oliveira https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981230Informative description of a project implementing a CIDOC-CRM based native graph database for representing megalithic informationRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper “Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph” describes an interesting endeavour of developing and implementing a CIDOC-CRM based knowledge graph using a native graph database (Neo4J) to represent megalithic information (Câmara et al. 2023). While there are earlier examples of using native graph databases and CIDOC-CRM in diverse heritage contexts, the present paper is useful addition to the literature as a detailed description of an implementation in the context of megalithic heritage. The paper provides a demonstration of a working implementation, and guidance for future projects. The described project is also documented to an extent that the paper will open up interesting opportunities to compare the approach to previous and forthcoming implementations. The same applies to the knowledge graph and use of CIDOC-CRM in the project. Readers interested in comparing available technologies and those who are developing their own knowledge graphs might have benefited of a more detailed description of the work in relation to the current state-of-the-art and what the use of a native graph database in the built-heritage contexts implies in practice for heritage documentation beyond that it is possible and it has potentially meaningful performance-related advantages. While also the reasons to rely on using plain CIDOC-CRM instead of extensions could have been discussed in more detail, the approach demonstrates how the plain CIDOC-CRM provides a good starting point to satisfy many heritage documentation needs. As a whole, the shortcomings relating to positioning the work to the state-of-the-art and reflecting and discussing design choices do not reduce the value of the paper as a valuable case description for those interested in the use of native graph databases and CIDOC-CRM in heritage documentation in general and the documentation of megalithic heritage in particular. ReferencesCâmara, A., de Almeida, A. and Oliveira, J. (2023). Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph, Zenodo, 7981230, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981230 | Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph | Ariele Câmara, Ana de Almeida, João Oliveira | <p>This paper presents a method to store information about megalithic monuments' building components as graph nodes in a knowledge graph (KG). As a case study we analyse the dolmens from the region of Pavia (Portugal). To build the KG, information... |  | Computational archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-29 13:46:49 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer