Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

23 Nov 2023

Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publicationSophie C Schmidt; Simon Maddison https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7966497Sharing Research Code in ArchaeologyRecommended by James Allison based on reviews by Thomas Rose, Joe Roe and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Thomas Rose, Joe Roe and 1 anonymous reviewer

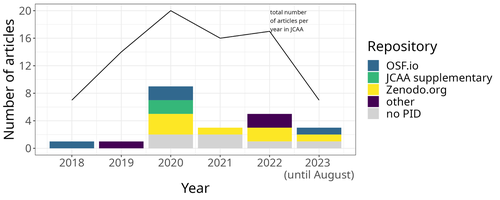

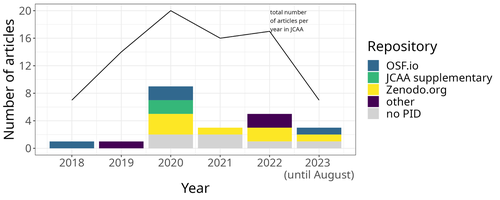

The paper “Percolation Package – From Script Sharing to Package Publication” by Sophie C. Schmidt and Simon Maddison (2023) describes the development of an R package designed to apply Percolation Analysis to archaeological spatial data. In an earlier publication, Maddison and Schmidt (2020) describe Percolation Analysis and provide case studies that demonstrate its usefulness at different spatial scales. In the current paper, the authors use their experience collaborating to develop the R package as part of a broader argument for the importance of code sharing to the research process. The paper begins by describing the development process of the R package, beginning with borrowing code from a geographer, refining it to fit archaeological case studies, and then collaborating to further refine and systematize the code into an R package that is more easily reusable by other researchers. As the review by Joe Roe noted, a strength of the paper is “presenting the development process as it actually happens rather than in an idealized form.” The authors also include a section about the lessons learned from their experience. Moving on from the anecdotal data of their own experience, the authors also explore code sharing practices in archaeology by briefly examining two datasets. One dataset comes from “open-archaeo” (https://open-archaeo.info/), an on-line list of open-source archaeological software maintained by Zack Batist. The other dataset includes articles published between 2018 and 2023 in the Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology. Schmidt and Maddison find that these two datasets provide contrasting views of code sharing in archaeology: many of the resources in the open-archaeo list are housed on Github, lack persistent object identifiers, and many are not easily findable (other than through the open-archaeo list). Research software attached to the published articles, on the other hand, is more easily findable either as a supplement to the published article, or in a repository with a DOI. The examination of code sharing in archaeology through these two datasets is preliminary and incomplete, but it does show that further research into archaeologists’ code-writing and code-sharing practices could be useful. Archaeologists often create software tools to facilitate their research, but how often? How often is research software shared with published articles? How much attention is given to documentation or making the software usable for other researchers? What are best (or good) practices for sharing code to make it findable and usable? Schmidt and Maddison’s paper provides partial answers to these questions, but a more thorough study of code sharing in archaeology would be useful. Differences among journals in how often they publish articles with shared code, or the effects of age, gender, nationality, or context of employment on attitudes toward code sharing seem like obvious factors for a future study to consider. Shared code that is easy to find and easy to use benefits the researchers who adopt code written by others, but code authors also have much to gain by sharing. Properly shared code becomes a citable research product, and the act of code sharing can lead to productive research collaborations, as Schmidt and Maddison describe from their own experience. The strength of this paper is the attention it brings to current code-sharing practices in archaeology. I hope the paper will also help improve code sharing in archaeology by inspiring more archaeologists to share their research code so other researchers can find and use (and cite) it. References Maddison, M.S. and Schmidt, S.C. (2020). Percolation Analysis – Archaeological Applications at Widely Different Spatial Scales. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 3(1), p.269–287. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcaa.54 Schmidt, S. C., and Maddison, M. S. (2023). Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publication, Zenodo, 7966497, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7966497 | Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publication | Sophie C Schmidt; Simon Maddison | <p>In this paper we trace the development of an R-package starting with the adaptation of code from a different field, via scripts shared between colleagues, to a published package that is being successfully used by researchers world-wide. Our aim... |  | Computational archaeology | James Allison | 2023-05-24 15:40:15 | View | |

05 Jan 2024

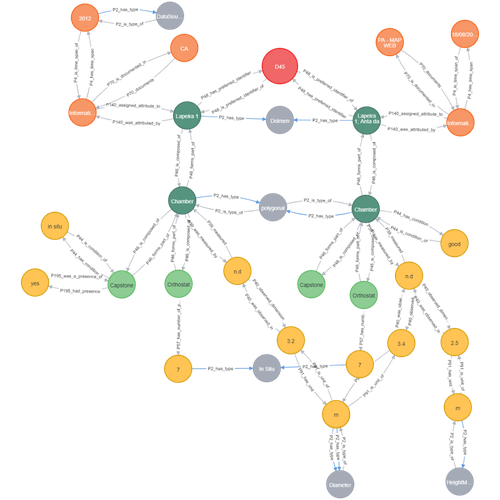

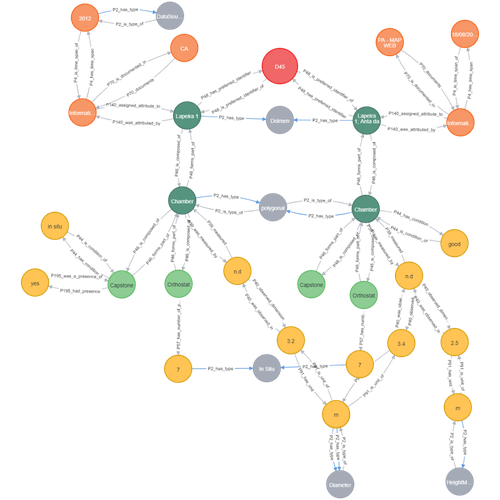

Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graphAriele Câmara, Ana de Almeida, João Oliveira https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981230Informative description of a project implementing a CIDOC-CRM based native graph database for representing megalithic informationRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper “Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph” describes an interesting endeavour of developing and implementing a CIDOC-CRM based knowledge graph using a native graph database (Neo4J) to represent megalithic information (Câmara et al. 2023). While there are earlier examples of using native graph databases and CIDOC-CRM in diverse heritage contexts, the present paper is useful addition to the literature as a detailed description of an implementation in the context of megalithic heritage. The paper provides a demonstration of a working implementation, and guidance for future projects. The described project is also documented to an extent that the paper will open up interesting opportunities to compare the approach to previous and forthcoming implementations. The same applies to the knowledge graph and use of CIDOC-CRM in the project. Readers interested in comparing available technologies and those who are developing their own knowledge graphs might have benefited of a more detailed description of the work in relation to the current state-of-the-art and what the use of a native graph database in the built-heritage contexts implies in practice for heritage documentation beyond that it is possible and it has potentially meaningful performance-related advantages. While also the reasons to rely on using plain CIDOC-CRM instead of extensions could have been discussed in more detail, the approach demonstrates how the plain CIDOC-CRM provides a good starting point to satisfy many heritage documentation needs. As a whole, the shortcomings relating to positioning the work to the state-of-the-art and reflecting and discussing design choices do not reduce the value of the paper as a valuable case description for those interested in the use of native graph databases and CIDOC-CRM in heritage documentation in general and the documentation of megalithic heritage in particular. ReferencesCâmara, A., de Almeida, A. and Oliveira, J. (2023). Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph, Zenodo, 7981230, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981230 | Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph | Ariele Câmara, Ana de Almeida, João Oliveira | <p>This paper presents a method to store information about megalithic monuments' building components as graph nodes in a knowledge graph (KG). As a case study we analyse the dolmens from the region of Pavia (Portugal). To build the KG, information... |  | Computational archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-29 13:46:49 | View | |

02 May 2024

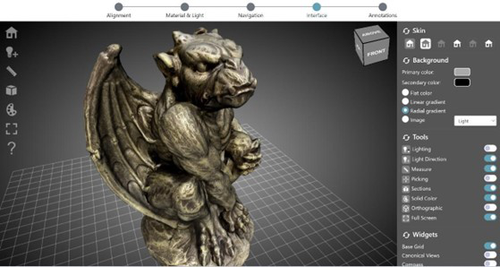

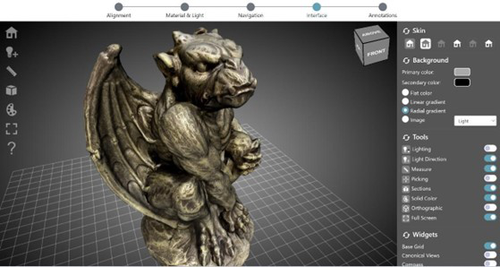

ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: toward full guided publication of high-resolution 3D dataPotenziani, Marco; Ponchio, Federico; Callieri, Marco; Cignoni, Paolo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8075050ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: a new tool for the visual organisation of 3D datasetsRecommended by Ian Moffat based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer, Vayia Panagiotidis, Erik Champion and Martina Trognitz based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer, Vayia Panagiotidis, Erik Champion and Martina Trognitz

The manuscript "ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: toward full guided publication of high-resolution 3D data" by Potenziani et al. [1] provides an excellent introduction to the Visual Media Service 3D Configurator. This is an exciting tool, focused on cultural heritage, that forms part of the Visual Media Service, a web-based platform for uploading a range of complex data sets, including high-resolution images, Reflectance Transformation Imaging images and 3D models and transforming them into an appropriate format for interation and visualisation on the web. The 3D Configurator Tool provides researchers with a wizard which assist with the presentation of 3D models. This manuscript provides a history and context for the development of the Visual Media Service and previous related tools such as 3DHOP, Nexus and Relight/OpenLIME. It also provides detailed information about the functionality of the 3D Configurator, including the Alignment, Material & Light, Navigation, Interface and Annotation steps. The Discussion section provides information about applications and users of the Visual Media Service, current limitations and planned future developments. Reviewers Hageneuer, Champion, Trognitz and Panagiotidis all provided important suggestions to the authors which have improved the clarity and scope of this manuscript. While this manscript does not present a case study using this tool, I recommend it to readers as a detailed and clear introduction to the Visual Media Service 3D configurator which may inspire them to use this for their own research. [1] Potenziani, M., Ponchio, F., Callieri, M., and Cignoni, P. (2024). ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: toward full guided publication of high-resolution 3D data. Zenodo, 8075050, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10894515 | ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: toward full guided publication of high-resolution 3D data | Potenziani, Marco; Ponchio, Federico; Callieri, Marco; Cignoni, Paolo | <p>The use of digital visual media in everyday work is nowadays a common practice in many different domains, including Cultural Heritage (CH). Because of that, the presence of digital datasets in CH archives and repositories is becoming more and m... |  | Computational archaeology | Ian Moffat | 2023-06-23 17:37:47 | View | |

28 Feb 2024

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and DutchAlex Brandsen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10610882Multilingual Named Entity Recognition in archaeology: an approach based on deep learningRecommended by Maria Pia di Buono based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch” (Brandsen 2024) explores the use of BERT-based models for Named Entity Recognition (NER) in archaeology across three languages: English, German, and Dutch. It introduces six models trained and fine-tuned on archaeological literature, followed by the presentation and evaluation of three models specifically tailored for NER tasks. The focus on multilingualism enhances the applicability of the research, while the meticulous evaluation using standard metrics demonstrates a rigorous methodology. The introduction of NER for extracting concepts from literature is intriguing, while the provision of a method for others to contribute to BERT model pre-training enhances collaborative research efforts. The innovative use of BERT models to contextualize archaeological data is a notable strength, bridging the gap between digitized information and computational models. Additionally, the paper's release of fine-tuned models and consideration of environmental implications add further value. In summary, the paper contributes significantly to the task of NER in archaeology, filling a crucial gap and providing foundational tools for data mining and reevaluating legacy archaeological materials and archives. Reference Brandsen, A. (2024). Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch. Zenodo, 8296920, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296920 | Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch | Alex Brandsen | <p>This short paper describes a collection of BERT models for the archaeology domain. We took existing language specific BERT models in English, German, and Dutch, and further pre-trained them with archaeology specific training data. We then took ... |  | Computational archaeology | Maria Pia di Buono | 2023-08-29 14:50:21 | View | |

16 Apr 2024

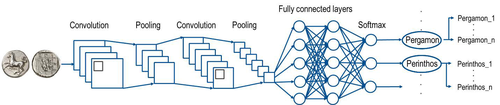

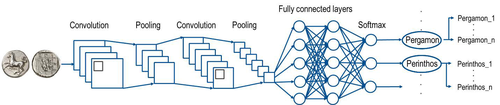

Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin DatasetSebastian Gampe, Karsten Tolle https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298077A significant contribution to the problem of unbalanced data in machine learning research in archaeologyRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by Simon Carrignon, Joel Santos and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Carrignon, Joel Santos and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper [1] presents an innovative approach to address the prevalent challenge of unbalanced datasets in coin type recognition, shifting the focus from coin class type recognition to coin mint recognition. Despite this shift, the issue of unbalanced data persists. To mitigate this, the authors introduce a method to split larger classes into smaller ones, integrating them into an 'additional class layer'. Three distinct machine learning (ML) methodologies were employed to identify new possible classes, with one approach utilising unsupervised clustering alongside manual intervention, while the others leverage object detection, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. However, despite these efforts, overfitting remained a persistent issue, prompting the authors to explore alternative methods such as dataset improvement and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). The paper contributes significantly to the intersection of ML techniques and archaeology, particularly in addressing overfitting challenges. Furthermore, the authors' candid acknowledgment of the limitations of their approaches serves as a valuable resource for researchers encountering similar obstacles. This study stems from the D4N4 project, aimed at developing a machine learning-based coin recognition model for the extensive "Corpus Nummorum" dataset, comprising over 19,600 coin types and 49,000 coins from various ancient landscapes. Despite encountering challenges with overfitting due to the dataset's imbalance, the authors' exploration of multiple methodologies and transparent documentation of their limitations enriches the academic discourse and provides a foundation for future research in this field. Reference [1] Gampe, S. and Tolle, K. (2024). Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin Dataset. Zenodo, 8298077, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298077 | Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin Dataset | Sebastian Gampe, Karsten Tolle | <p>We have implemented an approach based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for mint recognition for our Corpus Nummorum (CN) coin dataset as an alternative to coin type recognition, since we had too few instances for most of the types (classe... |  | Computational archaeology | Alex Brandsen | 2023-08-29 16:26:41 | View | |

14 May 2024

Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methodsChrisowalandis Deligio, Karsten Tolle, David Wigg-Wolf https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8301464A demonstration of the use and finetuning of existing machine learning tools for analysing large complexes of coinsRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The paper outlines the ClaReNet project's exploration of computer-based methods for classifying Celtic coin series, specifically focusing on a hoard from Jersey [1]. They collaborated with Jersey Heritage and numismatists, utilising a large dataset of coin images. The process involves stages such as pre-sorting, size-based sorting, class/type identification, and die studies. They employed IT methods, including object detection and unsupervised learning, followed by supervised learning for data refinement. Collaboration with numismatic experts ensured data quality. The study highlighted challenges in classifying coins, suggesting techniques like image matching alongside convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The results demonstrate the efficacy of semi-automatic processes in coin classification, emphasising the importance of human-computer collaboration for successful outcomes. Overall, this is a good paper, showing how we as archaeologists and numismatics can use existing tools and finetune them for our purposes; without the need for huge domain specific datasets. This research and related papers show how we can more effectively deal with the increasingly bigger data we deal with, saving time on the monotonous and labour intensive tasks, leaving us more time to deal with the big picture. An important strength of the work is the provided public software repository and the dataset. The paper is well written, and a number of images illustrate the methodology as well as the objects used. Reference [1] Deligio, C., Tolle, K., and Wigg-Wolf, D. (2024). Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methods. Zenodo, 8301464, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8301464

| Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methods | Chrisowalandis Deligio, Karsten Tolle, David Wigg-Wolf | <p>In the project "Classifications and Representations for Networks: From types and characteristics to linked open data for Celtic coinages" (ClaReNet) we had access to image data for one of the largest Celtic coin hoards ever found: Le Câtillon I... |  | Computational archaeology | Alex Brandsen | 2023-08-30 15:31:16 | View | |

02 Apr 2024

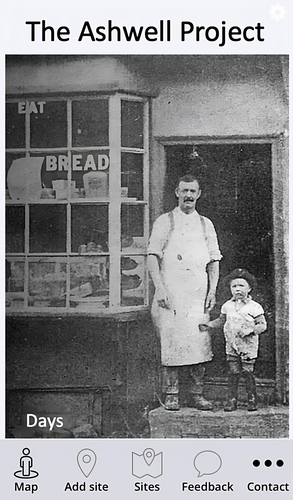

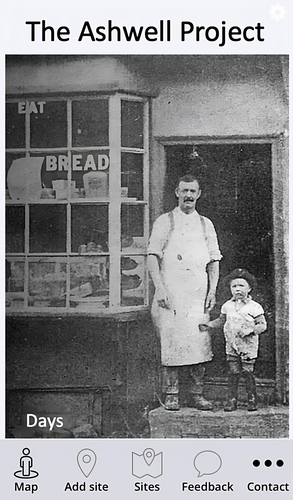

The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial CommunityAlphaeus Lien-Talks https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307882A nice project looking at under-represented demographicRecommended by Alexis Pantos based on reviews by Catriona Cooper and Steinar Kristensen based on reviews by Catriona Cooper and Steinar Kristensen

The paper by A. Lien-Talks [1] presents a small project looking at the use of crowd sourced data collection and particpatory GIS. In particular it looks at the potential of these tools in response to socially disruptive and isolating events such as the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the potential role of digitially mediated heritage initiatives in tackling some of the challenges of changing demographics and life styles. The types of technologies employed are relatively mature, the project identifies potential for such approaches to be used within the local-history/local community settings, though is also a reminer that depsite the much broader adoption of technology within all areas of society than even a few years ago many barriers still remain. While the the sample size and data collected in the project is relatively modest, the focus on empathy toward the intended audiences from the design process, as well as some of the qualitative feedback reported serve as a reminder that participatory, or crowd-sourced data collection initiatives in heritage can, and perhaps should place potential social benefit before data-acquisition of objectives. The project also presents a demographic that is not often represented within the literature and the publication and as such the publication of the article represents a meaningful contribution to ongoing discussions of the role heritage and digitally mediated community archaeology can play a role in developing our societies. References [1] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial Community. Zenodo, 8307882, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307882 | The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial Community | Alphaeus Lien-Talks | <p>Background:<br>As the world becomes increasingly digital, so too must the way in which archaeologists engage with the public. This was particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic, and many outreach and engagement efforts began to move o... |  | Computational archaeology | Alexis Pantos | 2023-09-01 11:25:54 | View | |

31 Jan 2024

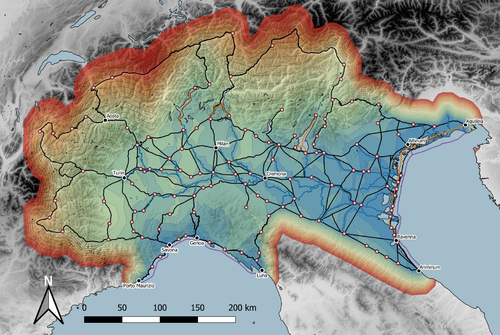

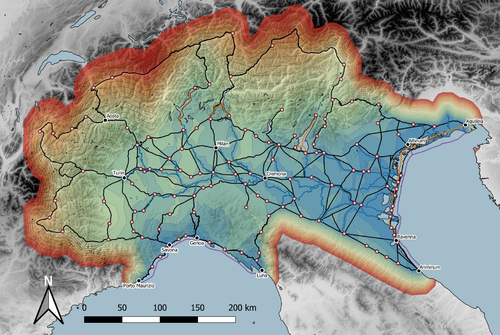

Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman periodJames Page https://zenodo.org/records/7971399Modelling Roman Transport Infrastructure in Northern ItalyRecommended by Andrew McLean based on reviews by Pau de Soto and Adam PažoutStudies of the economy of the Roman Empire have become increasingly interdisciplinary and nuanced in recent years, allowing the discipline to make great strides in data collection and importantly in the methods through which this increasing volume of data can be effectively and meaningfully analysed [see for example 1 and 2]. One of the key aspects of modelling the ancient economy is understanding movement and transport costs, and how these facilitated trade, communication and economic development. With archaeologists adopting more computational techniques and utilising GIS analysis beyond simply creating maps for simple visualisation, understanding and modelling the costs of traversing archaeological landscapes has become a much more fruitful avenue of research. Classical archaeologists are often slower to adopt these new computational techniques than others in the discipline. This is despite (or perhaps due to) the huge wealth of data available and the long period of time over which the Roman economy developed, thrived and evolved. This all means that the Roman Empire is a particularly useful proving ground for testing and perfecting new methodological developments, as well as being a particularly informative period of study for understanding ancient human behaviour more broadly. This paper by Page [3] then, is well placed and part of a much needed and growing trend of Roman archaeologists adopting these computational approaches in their research. Page’s methodology builds upon De Soto’s earlier modelling of transport costs [4] and applies it in a new setting. This reflects an important practice which should be more widely adopted in archaeology. That of using existing, well documented methodologies in new contexts to offer wider comparisons. This allows existing methodologies to be perfected and tested more robustly without reinventing the wheel. Page does all this well, and not only builds upon De Soto’s work, but does so using a case study that is particularly interesting with convincing and significant results. As Page highlights, Northern Italy is often thought of as relatively isolated in terms of economic exchange and transport, largely due to the distance from the sea and the barriers posed by the Alps and Apennines. However, in analysing this region, and not taking such presumptions for granted, Page quite convincingly shows that the waterways of the region played an important role in bringing down the cost of transport and allowed the region to be far more interconnected with the wider Roman world than previous studies have assumed. This article is clearly a valuable and important contribution to our understanding of computational methods in archaeology as well as the economy and transport network of the Roman Empire. The article utilises innovative techniques to model transport in an area of the Roman Empire that is often overlooked, with the economic isolation of the area taken for granted. Having high quality research such as this specifically analysing the region using the most current methodologies is of great importance. Furthermore, developing and improving methodologies like this allow for different regions and case studies to be analysed and directly compared, in a way that more traditional analyses simply cannot do. As such, Page has demonstrated the importance of reanalysing traditional assumptions using the new data and analyses now available to archaeologists. References [1] Brughmans, T. and Wilson, A. (eds.) (2022). Simulating Roman Economies: Theories, Methods, and Computational Models. Oxford. [2] Dodd, E.K. and Van Limbergen, D. (eds.) (2024). Methods in Ancient Wine Archaeology: Scientific Approaches in Roman Contexts. London ; New York. [3] Page, J. (2024). Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman period, Zenodo, 7971399, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7971399 [4] De Soto P (2019). Network Analysis to Model and Analyse Roman Transport and Mobility. In: Finding the Limits of the Limes. Modelling Demography, Economy and Transport on the Edge of the Roman Empire. Ed. by Verhagen P, Joyce J, and Groenhuijzen M. Springer Open Access, pp. 271–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04576-0_13 | Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman period | James Page | <p>Northern Italy has often been characterised as an isolated and marginal area during the Roman period, a region constricted by mountain ranges and its distance from major shipping lanes. Historians have frequently cited these obstacles, alongsid... |  | Classic, Computational archaeology | Andrew McLean | 2023-05-28 15:11:31 | View | |

26 Mar 2024

What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery.Philippe Boissinot https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433Abstract and Concrete – Querying the Metaphysics and Geometry of Pottery ClassificationRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

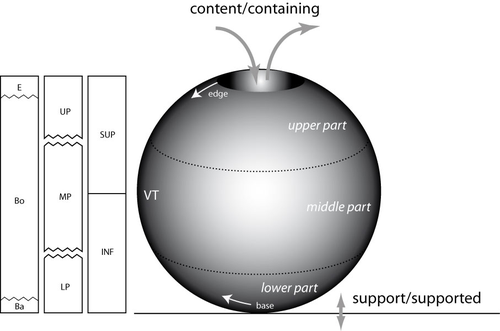

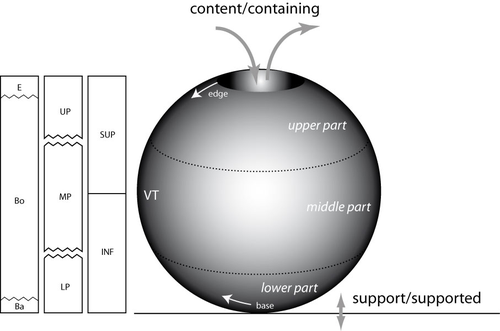

“What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery” by P. Boissinot (1) is a timely contribution to broader theoretical reflections on classification and ordering practices in archaeology, including type-construction and justification. Boissinot rightly reminds us that engagement with the type concept always touches upon the uneasy relationship between the abstract and the concrete, alternatively cast as the ongoing struggle in knowledge production between idealization and particularization. Types are always abstract and as such both ‘more’ and ‘less’ than the concrete objects they refer to. They are ‘more’ because they establish a higher-order identity of variously heterogeneous, concrete objects and they are ‘less’ because they necessarily reduce the richness of the concrete and often erase it altogether. The confusion that types evoke in archaeology and elsewhere has therefore a lot to do with the fact that types are simply not spatiotemporally distinct particulars. As abstract entities, types so almost automatically re-introduce the question of universalism but they do not decide this question, and Boissinot also tentatively rejects such ambitions. In fact, with Boissinot (1) it may be said that universality is often precisely confused with idealization, which is indispensable to all archaeological ordering practices. Idealization, increasingly recognized as an important epistemic operation in science (2, 3), paradoxically revolves around the deliberate misrepresentation of the empirical systems being studied, with models being the paradigm cases (4). Models can go so far as to assume something strictly false about the phenomena under consideration in order to advance their epistemic goals. In the words of Angela Potochnik (5), ‘the role of idealization in securing understanding distances understanding from truth but […] this understanding nonetheless gives rise to scientific knowledge’. The affinity especially to models may in part explain why types are so controversial and are often outright rejected as ‘real’ or ‘useful’ by those who only recognize the existence of concrete particulars (nominalism). As confederates of the abstract, types thus join the ranks of mathematics and geometry, which the author identifies as prototypical abstract systems. Definitions are also abstract. According to Boissinot (1), they delineate a ‘position of limits’, and the precision and rigorousness they bring comes at the cost of subjectivity. This unites definitions and types, as both can be precise and clear-cut but they can never be strictly singular or without alternative – in order to do so, they must rely on yet another higher-order system of external standards, and so ad infinitum. Boissinot (1) advocates a mathematical and thus by definition abstract approach to archaeological type-thinking in the realm of pottery, as the abstractness of this approach affords relatively rigorous description based on the rules of geometry. Importantly, this choice is not a mysterious a priori rooted in questionable ideas about the supposed superiority of such an approach but rather is the consequence of a careful theoretical exploration of the particularities (domain-specificities) of pottery as a category of human practice and materiality. The abstract thus meets the concrete again: objects of pottery, in sharp contrast to stone artefacts for example, are the product of additive processes. These processes, moreover, depend on the ‘fusion’ of plastic materials and the subsequent fixation of the resulting configuration through firing (processes which, strictly speaking, remove material, such as stretching, appear to be secondary vis-à-vis global shape properties). Because of this overriding ‘fusion’ of pottery, the identification of parts, functional or otherwise, is always problematic and indeterminate to some extent. As products of fusion, parts and wholes represent an integrated unity, and this distinguishes pottery from other technologies, especially machines. The consequence is that the presence or absence of parts and their measurements may not be a privileged locus of type-construction as they are in some biological contexts for example. The identity of pottery objects is then generally bound to their fusion. As a ‘plastic montage’ rather than an assembly of parts, individual parts cannot simply be replaced without threatening the identity of the whole. Although pottery can and must sometimes be repaired, this renders its objects broadly morpho-static (‘restricted plasticity’) rather than morpho-dynamic, which is a condition proper to other material objects such as lithic (use and reworking) and metal artefacts (deformation) but plays out in different ways there. This has a number of important implications, namely that general shape and form properties may be expected to hold much more relevant information than in technological contexts characterized by basal modularity or morpho-dynamics. It is no coincidence that ‘fusion’ is also emphasized by Stephen C. Pepper (6) as a key category of what he calls contextualism. Fusion for Pepper pays dividends to the interpenetration of different parts and relations, and points to a quality of wholes which cannot be reduced any further and integrates the details into a ‘more’. Pepper maintains that ‘fusion, in other words, is an agency of simplification and organization’ – it is the ‘ultimate cosmic determinator of a unit’ (p. 243-244, emphasis added). This provides metaphysical reasons to look at pottery from a whole-centric perspective and to foreground the agency of its materiality. This is precisely what Boissinot (1) does when he, inspired by the great techno-anthropologist François Sigaut (7), gestures towards the fact that elementarily a pot is ‘useful for containing’. He thereby draws attention not to the function of pottery objects but to what pottery as material objects do by means of their material agency: they disclose a purposive tension between content and container, the carrier and carried as well as inclusion and exclusion, which can also be understood as material ‘forces’ exerted upon whatever is to be contained. This, and not an emic reading of past pottery use, leads to basic qualitative distinctions between open and closed vessels following Anna O. Shepard’s (8) three basic pottery categories: unrestricted, restricted, and necked openings. These distinctions are not merely intuitive but attest to the object-specificity of pottery as fused matter. This fused dimension of pottery also leads to a recognition that shapes have geometric properties that emerge from the forced fusion of the plastic material worked, and Boissinot (1) suggests that curvature is the most prominent of such features, which can therefore be used to describe ‘pure’ pottery forms and compare abstract within-pottery differences. A careful mathematical theorization of curvature in the context of pottery technology, following George D. Birkhoff (9), in this way allows to formally distinguish four types of ‘geometric curves’ whose configuration may serve as a basis for archaeological object grouping. The idealization involved in this proposal is not accidental but deliberately instrumental – it reminds us that type-thinking in archaeology cannot escape the abstract. It is notable here that the author does not suggest to simply subject total pottery form to some sort of geometric-morphometric analysis but develops a proposal that foregrounds a limited range of whole-based geometric properties (in contrast to part-based) anchored in general considerations as to the material specificity of pottery as quasi-species of objects. As Boissinot (1) notes himself, this amounts to a ‘naturalization’ of archaeological artefacts and offers somewhat of an alternative (a third way) to the old discussion between disinterested form analysis and functional (and thus often theory-dependent) artefact groupings. He thereby effectively rejects both of these classic positions because the first ignores the particularities of pottery and the real function of artefacts is in most cases archaeologically inaccessible. In this way, some clear distance is established to both ethnoarchaeology and thing studies as a project. Attending to the ‘discipline of things’ proposal by Bjørnar Olsen and others (10, 11), and by drawing on his earlier work (12), Boissinot interestingly notes that archaeology – never dealing with ‘complete societies’ – could only be ‘deficient’. This has mainly to do with the underdetermination of object function by the archaeological record (and the confusion between function and functionality) as outlined by the author. It seems crucial in this context that Boissinot does not simply query ‘What is a thing?’ as other thing-theorists have previously done, but emphatically turns this question into ‘In what way is it not the same as something else?’. He here of course comes close to Olsen’s In Defense of Things insofar as the ‘mode of being’ or the ‘ontology’ of things is centred. What appears different, however, is the emphasis on plurality and within-thing heterogeneity on the level of abstract wholes. With Boissinot, we always have to speak of ontologies and modes of being and those are linked to different kinds of things and their material specificities. Theorizing and idealizing these specificities are considered central tasks and goals of archaeological classification and typology. As such, this position provides an interesting alternative to computational big-data (the-more-the-better) approaches to form and functionally grounded type-thinking, yet it clearly takes side in the debate between empirical and theoretical type-construction as essential object-specific properties in the sense of Boissinot (1) cannot be deduced in a purely data-driven fashion. Boissinot’s proposal to re-think archaeological types from the perspective of different species of archaeological objects and their abstract material specificities is thought-provoking and we cannot stop wondering what fruits such interrogations would bear in relation to other kinds of objects such as lithics, metal artefacts, glass, and so forth. In addition, such meta-groupings are inherently problematic themselves, and they thus re-introduce old challenges as to how to separate the relevant super-wholes, technological genesis being an often-invoked candidate discriminator. The latter may suggest that we cannot but ultimately circle back on the human context of archaeological objects, even if we, for both theoretical and epistemological reasons, wish to embark on strictly object-oriented archaeologies in order to emancipate ourselves from the ‘contamination’ of language and in-built assumptions.

Bibliography 1. Boissinot, P. (2024). What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery, Zenodo, 7429330, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433 2. Fletcher, S.C., Palacios, P., Ruetsche, L., Shech, E. (2019). Infinite idealizations in science: an introduction. Synthese 196, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02069-6 3. Potochnik, A. (2017). Idealization and the aims of science (University of Chicago Press). https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226507194.001.0001 4. J. Winkelmann, J. (2023). On Idealizations and Models in Science Education. Sci & Educ 32, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00291-2 5. Potochnik, A. (2020). Idealization and Many Aims. Philosophy of Science 87, 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1086/710622 6. Pepper S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (University of California Press). 7. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l’analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d’études Technologiques En Préhistoire. Bilan et Perspectives (Association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques), pp. 21–34. 8. Shepard, A. O. (1956). Ceramics for the Archeologist (Carnegie Institution of Washington n° 609). 9. Birkhoff G. D. (1933). Aesthetic Measure (Harvard University Press). 10. Olsen, B. (2010). In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects (AltaMira Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/ept014 11. Olsen, B., Shanks, M., Webmoor, T., Witmore, C. (2012). Archaeology: the discipline of things (University of California Press). https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520954007 12. Boissinot, P. (2011). “Comment sommes-nous déficients ?” in L’archéologie Comme Discipline ? (Le Seuil), pp. 265–308. | What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery. | Philippe Boissinot | <p>The main question we want to ask here concerns the application of philosophical considerations on identity about artifacts of a particular kind (pottery). The purpose is the recognition of types and their classification, which are two of the ma... |  | Ceramics, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2022-12-13 15:04:45 | View | |

02 May 2023

Transmission of lithic and ceramic technical know-how in the Early Neolithic of central-western Europe: Shedding Light on the Social Mechanisms underlying Cultural TransitionSolène Denis, Louise Gomart, Laurence Burnez-Lanotte, Pierre Allard https://osf.io/gqnht/A Thought Provoking Consideration of Craft in the NeolithicRecommended by Clare Burke based on reviews by Bogdana Milić and 1 anonymous reviewerThe pioneering work of Leroi-Gourhan introduced archaeologists to the concept of the chaîne opératoire[1], whereby, like his supervisor Mauss[2], Leroi-Gourhan proposed direct links between bodily actions and aspects of cultural identity. The chaîne opératoire offers a powerful conceptual tool with which to reconstruct and describe the technological practices undertaken by craftspeople, linking material objects to the cultural context in which crafts are learnt. Although initially applied to lithics, the concept today is well known in ceramic studies, as well as, other material crafts, in order to identify aspects of tradition and identity through ideas linked to technological style[3,4] and communities of practice[5]. Utilizing this approach, Denis et al.[6] use the chaîne opératoire to look at both lithics and ceramics together from a diachronic viewpoint, to examine technical systems present over the transition between Linearbandkeramic (LBK) and post LBK Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint German (BQY/VSG) timeframes. This much needed comparative and diachronic perspective, focuses on material from the sites of Vaux-et-Borset and Verlaine in Belgium, and has enabled the authors to consider the impact of changing social dynamics on these two crafts simultaneously. The authors examine the ceramic and lithic assemblages from a macroscopic and morphological perspective in order to identify techniques of production. The data gathered testifies to the dominance of one production technique for each craft within the LBK. There is particularly striking homogeneity noted for the lithics that suggests the transmission of a single tradition over the Hesbaye area, whilst the ceramics display greater regional diversity. The picture alters somewhat for the BQY/VSG material where it seems there is an increase in the diversity of production techniques, with both the introduction of new techniques, as well as a degree of hybridization of earlier techniques to form new BQY/VSG chaînes opératoires that have LBK roots. The BQY/VSG diversity noted for the lithics is especially interesting, with the introduction of techniques that attest to increased expertise which the authors attest to the migration of an external group. The results of this work have allowed Denis et al. to discuss multiple influences on the technical systems they identify. Rather than trying to fit the data within a single model, the authors demonstrate the need for nuance, considering the social changes associated with Neolithic migration and interactions, as multifaced and dynamic. As such, they are able to show not only the influence of contact with other groups, but that the apparent migration of external groups does not simply lead to the replacement of the crafting heritage already established at the sites they have examined. In concluding the authors acknowledge, that as scholars push the existing state of knowledge (in this respect analysis of raw materials would make an especially important contribution), the picture presented in the paper may alter. Future work will hopefully fill in current gaps, particularly in terms of how far the trends identified extend, and the extent to which the lithic and ceramic pictures diversify on a broader geographical scale. It is certain that based on such results, future work should adopt the comparative approach presented by the authors, who have demonstrated its explanatory potential for understanding the technical and cultural groups we all study. [2] Mauss, M. 2009 [1934]. Techniques, Technology and Civilisation. Edited and introduced by N. Schlanger. New York/Oxford: Durkheim Press/Berghahn Books. [3] Lechtman, H. 1977. Style in Technology: some early thoughts. In H. Lechtman and R.S. Merrill (eds.) Material Culture: styles, organization and dynamics of technology. Proceedings of the American Ethnological Society 1975, St. Paul, 3-20. [4] Gosselain, O. 1992. Technology and Style: Potters and Pottery Among Bafia of Cameroon. Man 27(3) 559- 586. htpps://doi.org/10.2307/2803929. [5] Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [6] Denis, S., Gomart, L., Burnez-Lanotte, L. and Allard, P. (2023). Transmission of lithic and ceramic technical know-how in the Early Neolithic of central-western Europe: Shedding Light on the Social Mechanisms underlying Cultural Transition. OSF Preprints, gqnht, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/gqnht

| Transmission of lithic and ceramic technical know-how in the Early Neolithic of central-western Europe: Shedding Light on the Social Mechanisms underlying Cultural Transition | Solène Denis, Louise Gomart, Laurence Burnez-Lanotte, Pierre Allard | <p>Research on the European Neolithisation agrees that a process of colonisation throughout the sixth millennium BC underlies the spread of agricultural ways of life on the continent. From central to central-western Europe, this colonisation path ... |  | Ceramics, Europe, Lithic technology, Neolithic | Clare Burke | 2022-11-18 12:03:55 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer