Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture▼ | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

17 Jun 2022

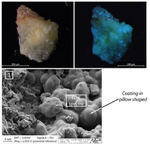

Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France)Marine Quiers, Claire Chanteraud, Andréa Maris-Froelich, Émilie Chalmin-Aljanabi, Stéphane Jaillet, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Pairis, Yves Perrette, Hélène Salomon, Julien Monney https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03383193v5New method for the in situ detection and characterisation of amorphous silica in rock art contextsRecommended by Aitor Ruiz-Redondo based on reviews by Alain Queffelec, Laure Dayet and 1 anonymous reviewerSilica coating developed in cave art walls had an impact in the preservation of the paintings themselves. Despite it still exists a controversy about whether or not the effects contribute to the preservation of the artworks; it is evident that identifying these silica coatings would have an impact to assess the taphonomy of the walls and the paintings preserved on them. Unfortunately, current techniques -especially non-invasive ones- can hardly address amorphous silica characterisation. Thus, its presence is often detected on laboratory observations such as SEM or XRD analyses. In the paper “Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context - Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France)”, Quiers and collaborators propose a new method for the in situ detection and characterisation of amorphous silica in a rock art context based on UV laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) and UV illumination [1]. The results from both methods presented by the authors are convincing for the detection of U-silica mineralisation (U-opal in the specific case of study presented). This would allow access to a fast and cheap method to identify this kind of formations in situ in decorated caves. Beyond the relationship between opal coating and the preservation of the rock art, the detection of silica mineralisation can have further implications. First, it can help to define spot for sampling for pigment compositions, as well as reconstruct the chronology of the natural history of the caves and its relation with the human frequentation and activities. In conclusion, I am glad to recommend this original research, which offers a new approach to the identification of geological processes that affect -and can be linked with- the Palaeolithic cave art. [1] Quiers, M., Chanteraud, C., Maris-Froelich, A., Chalmin-Aljanabi, E., Jaillet, S., Noûs, C., Pairis, S., Perrette, Y., Salomon, H., Monney, J. (2022) Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France). HAL, hal-03383193, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03383193v5 | Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France) | Marine Quiers, Claire Chanteraud, Andréa Maris-Froelich, Émilie Chalmin-Aljanabi, Stéphane Jaillet, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Pairis, Yves Perrette, Hélène Salomon, Julien Monney | <p style="text-align: justify;">Silica coatings development on rock art walls in Points Cave questions the analytical access to pictorial matter specificities (geochemistry and petrography) and the rock art conservation state in the context of pig... |  | Archaeometry, Europe, Rock art, Taphonomy, Upper Palaeolithic | Aitor Ruiz-Redondo | 2021-10-25 11:12:48 | View | |

14 Sep 2020

A way to break bones? The weight of intuitivenessDelphine Vettese, Trajanka Stavrova, Antony Borel, Juan Marin, Marie-Hélène Moncel, Marta Arzarello, Camille Daujeard https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/rebwtBreaking bones: Nature or Culture?Recommended by Beatrice Demarchi and Reuven Yeshurun based on reviews by Terry O'Connor, Alan Outram and 1 anonymous reviewerThe nature of breaking long bones for obtaining marrow is important in Paleolithic archaeology, due to its widespread, almost universal, character. Provided that hammer-stone percussion marks can be correctly identified using experimental datasets (e.g., [1]), the anatomical location and count of the marks may be taken to reflect recurrent “cultural” traditions in the Paleolithic [2]. Were MP humans breaking bones intuitively or did they abide by a strict “protocol”, and, if the latter, was this protocol optimized for marrow retrieval or geared towards another, less obvious goal? This paper provides a baseline for location analyses of percussion marks. Their dataset may therefore be regarded as a null hypothesis according to which the archaeological data could be tested. If Paleolithic patterns of percussion marks differ from Vettese et al.’s [3] “intuitive” patterns, then the null hypothesis is disproved and one can argue in favor of a learned pattern. The latter can be a result of ”culture”, as Vettese et al. [3] phrase it, in the sense of nonrandom action that draws on transmitted knowledge. Such comparisons bear a great potential for understanding the degree of technological behavior in the Paleolithic by factoring out the “natural” constraints of bone breakage patterns. Vettese et al. [3: fig. 14] started this discourse by comparing their experimental dataset to some Middle and Upper Paleolithic faunas; we are confident that many other studies will follow. Bibliography [1]Pickering, T.R., Egeland, C.P., 2006. Experimental patterns of hammerstone percussion damage on bones: Implications for inferences of carcass processing by humans. J. Archaeol. Sci. 33, 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.09.001 [2]Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Domínguez-Rodrigo, M., Lozano, S., Pastó, I., Riba, D., Vaquero, M., Peris, J.F., Arsuaga, J.L., de Castro, J.M.B., Carbonell, E., 2013. Learning by Heart: Cultural Patterns in the Faunal Processing Sequence during the Middle Pleistocene. PLoS One 8, e55863. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055863 [3]Vettese, D., Stavrova, T., Borel, A., Marin, J., Moncel, M.-H., Arzarello, M., Daujeard, C. (2020) A way to break bones? The weight of intuitiveness. BioRxiv, 011320, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.31.011320 | A way to break bones? The weight of intuitiveness | Delphine Vettese, Trajanka Stavrova, Antony Borel, Juan Marin, Marie-Hélène Moncel, Marta Arzarello, Camille Daujeard | <p>During the Middle Paleolithic period, bone marrow extraction was an essential source of fat nutrients for hunter-gatherers especially throughout cold and dry seasons. This is attested by the recurrent findings of percussion marks in osteologica... |  | Archaeometry, Bioarchaeology, Spatial analysis, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Beatrice Demarchi | 2020-04-01 11:52:05 | View | |

12 Feb 2024

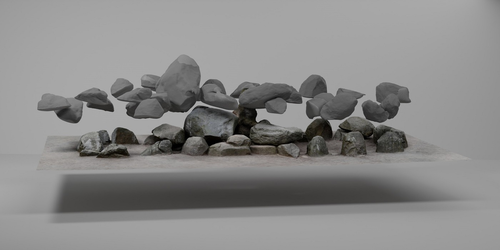

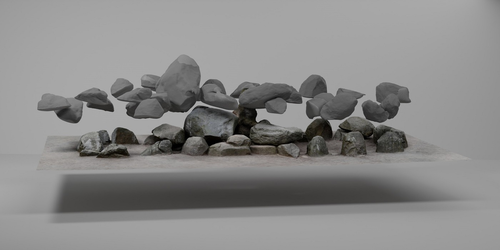

3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, GermanyTharandt, Louise https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7948379Online presentation of the digital reconstruction process of a megalithic tomb : “3Duewelsteene”Recommended by Sophie C. Schmidt and James Allison based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Ronald Visser and Scott Ure based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Ronald Visser and Scott Ure

“3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, Germany” (Tharandt 2024) presents several 3-dimensional models of the Düwelsteene monument, along with contextual information about the grave and the process of creating the models. The website (https://3duewelsteene.github.io/) includes English and German versions, making it accessible to a wide audience. The website itself serves as the primary means of presenting the data, rather than as a supplement to a written text. This is an innovative and engaging way to present the research to a wider public. Düwelsteene (“Devil’s Stones”) is a megalithic passage grave from the Funnel Beaker culture, dating to approximately 3300 BC. to 2600 BC. that was excavated in 1932. The website displays three separate 3-dimensional models. They ares shown in the 3D viewer software 3DHOP, which enables viewers to interact with the models in several ways, Annotations on the models display further information. The first model was created by image-based modeling and shows the monument as it appears today. A second model uses historical photographs and excavation data to reconstruct the grave as it appeared prior to the 1932 archaeological excavation. Restoration work following the excavation relocated many of the stones. Pre-1932 photographs collected from residents of the nearby town of Heiden were then used to create a model showing what the tomb looked like before the restoration work. It is commendable that a “certainty view” of the model shows the certainty with which the stones can be put at the reconstructed place. Gaps in the 3D models of stones that were caused by overlap with other stones have been filled with a rough mesh and marked as such, thereby differentiating between known and unknown parts of the stones. The third model is the most imaginative and most interesting. As it shows as the grave as it might have appeared in approximately 3000 B.C., many aspects of this model are necessarily somewhat speculative. There is no direct evidence for exact size and shape of the capstones, the height of the mound, and other details. But enough is known about other similar constructions to allow these details to be inferred with some confidence. Again, care was taken to enable viewers to distinguish between the stones that are still in existence and those that were reconstructed. A video on the home page of the website adds a nice touch. It starts with the model of the Düwelsteene as it currently appears then shows, in reverse order, the changes to the grave, ending with the inferred original state. The 3D reconstructions are convincing and the methods well described. This project follows an open science approach and the FAIR principles, which is commendable and cutting edge in the field of Digital Archaeology. The preprint of the website hosted on zenodo includes all the photos, text, html files, and nine individual 3D model (.ply) files that are combined in the reconstructions exhibited on the website. A “readme.md” file includes details about building the models using CloudCompare and Blender, and modifications to the 3D viewer software (3DHOP) to get the website to improve the display of the reconstructions. We have to note that the link between the reconstructed models and the html page does not work when the files are downloaded from zenodo and opened offline. The html pages open in the browser, and the individual ply files work fine, but the 3D models do not display on the browser page when the html files are opened offline. The online version of the website is working perfectly. The 3Düwelsteene website combines the presentation of archaeological domain knowledge to a lay audience as well as in-depths information on the reconstruction process to make it an interesting contribution for researchers. By providing data and code for the website it also models an Open Science approach, which enables other researchers to re-use these materials. We congratulate the author on a successful reconstruction of the megalithic tomb, an admirable presentation of the archaeological work and the thoughtful outreach to a broad audience. Bibliography | 3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, Germany | Tharandt, Louise | <p>The Düwelsteene near Heiden, Westphalia, is one of the most southern megalithic tombs of the Funnel Beaker culture. In 1932 the Düwelsteene were restored and the appearance of the grave was changed. Even though the megalithic tomb was excavated... |  | Computational archaeology, Mesolithic, Neolithic | Sophie C. Schmidt | 2023-05-21 17:24:22 | View | |

04 Oct 2023

IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A "para-description"Hagmann, Dominik; Reiner, Franziska https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5vwg8The IUENNA project: integrating old data and documentation for future archaeologyRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Nina Richards and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Nina Richards and 3 anonymous reviewers

This recommended paper on the IUENNA project (Hagmann and Reiner 2023) is not a paper in the traditional sense, but it is a reworked version of a project proposal. It is refreshing to read about a project that has just started and see what the aims of the project are. This ties in with several open science ideas and standards (e.g. Brinkman et al. 2023). I am looking forward to see in a few years how the authors managed to reach the aims and goals of the project. The IUENNA project deals with the legacy data and old excavations on the Hemmaberg and in the Jauntal. Archaeological research in this small, but important region, has taken place for more than a century, revealing material from over 2000 years of human history. The Hemmaberg is well known for its late antique and early medieval structures, such as roads, villas and the various churches. The wider Jauntal reveals archaeological finds and features dating from the Iron Age to the recent past. The authors of the paper show the need to make sure that the documentation and data of these past archaeological studies and projects will be accessible in the future, or in their own words: "Acute action is needed to systematically transition these datasets from physical filing cabinets to a sustainable, networked virtual environment for long-term use" (Hagmann and Reiner 2023: 5). The papers clearly shows how this initiative fits within larger developments in both Digital Archaeology and the Digital Humanities. In addition, the project is well grounded within Austrian archaeology. While the project ties in with various international standards and initiatives, such as Ariadne (https://ariadne-infrastructure.eu/) and FAIR-data standards (Wilkinson et al. 2016, 2019), it would benefit from the long experience institutes as the ADS (https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/) and DANS (see Data Station Archaeology: https://dans.knaw.nl/en/data-stations/archaeology/) have on the storage of archaeological data. I would also like to suggest to have a look at the Dutch SIKB0102 standard (https://www.sikb.nl/datastandaarden/richtlijnen/sikb0102) for the exchange of archaeological data. The documentation is all in Dutch, but we wrote an English paper a few years back that explains the various concepts (Boasson and Visser 2017). However, these are a minor details or improvements compared to what the authors show in their project proposal. The integration of many standards in the project and the use of open software in a well-defined process is recommendable. The IUENNA project is an ambitious project, which will hopefully lead to better insights, guidelines and workflows on dealing with legacy data or documentation. These lessons will hopefully benefit archaeology as a discipline. This is important, because various (European) countries are dealing with similar problem, since many excavations of the past have never been properly published, digitalized or deposited. In the Netherlands, for example, various projects dealt with publication of legacy excavations in the Odyssee-project (https://www.nwo.nl/onderzoeksprogrammas/odyssee). This has led to the publication of various books and datasets (24) (https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:34359), but there are still many datasets (8) missing from the various projects. In addition, each project followed their own standards in creating digital data, while IUENNA will make an effort to standardize this. There are still more than 1000 Dutch legacy excavations still waiting to be published and made into a modern dataset (Kleijne 2010) and this is probably the case in many other countries. I sincerely hope that a successful end of IUENNA will be an inspiration for other regions and countries for future safekeeping of legacy data. References Boasson, W and Visser, RM. 2017 SIKB0102: Synchronizing Excavation Data for Preservation and Re-Use. Studies in Digital Heritage 1(2): 206–224. https://doi.org/10.14434/sdh.v1i2.23262 Brinkman, L, Dijk, E, Jonge, H de, Loorbach, N and Rutten, D. 2023 Open Science: A Practical Guide for Early-Career Researchers https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7716153 Hagmann, D and Reiner, F. 2023 IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A ‘para-description’. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5vwg8 Kleijne, JP. 2010. Odysee in de breedte. Verslag van het NWO Odyssee programma, kortlopend onderzoek: ‘Odyssee, een oplossing in de breedte: de 1000 onuitgewerkte sites, die tot een substantiële kennisvermeerdering kunnen leiden, digitaal beschikbaar!’ ‐ ODYK‐09‐13. Den Haag: E‐depot Nederlandse Archeologie (EDNA). https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-z25-g4jw Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Aalbersberg, IjJ, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, ’t Hoen, PAC, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Velterop, J, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2016 The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1): 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Jan Aalbersberg, I, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, Hoen, PAC ’t, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Jan Velterop, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2019 Addendum: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 6(1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0009-6

| IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A "para-description" | Hagmann, Dominik; Reiner, Franziska | <p>The Go!Digital 3.0 project IUENNA – an acronym for “openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology” – embraces a comprehensive open science methodology. It focuses on the archaeological micro-region of the Jauntal Valley ... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Computational archaeology | Ronald Visser | 2023-04-06 13:36:16 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific RegionChristopher Buckley https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2From Polished Stone Tools to Population Dynamics: Ethnographic Archives as InsightsRecommended by Solène Denis based on reviews by Adrian L. Burke and 1 anonymous reviewerMost archaeological contexts provide objects without organic materials making them quite silent regarding their hafting techniques and use. This is especially true for the polished stone tools that only thanks to a few discoveries in a wet environment, we can obtain some insights regarding their hafting techniques. Use-wear analysis can also be of some support to get a better picture of these artefacts (e.g. Masclans Latorre 2020), whose typology testifies to an important diversity in European Neolithic contexts that sometimes are well-documented from the chaîne opératoire perspective (see De Labriffe and Thirault dir. 2012). The study offered by Chris Buckley (2023) constitutes an important contribution to animating these tools. His work relies on the Asia Pacific region, where he gathered data and mapped more than 300 ethnographic hafted stone and shell tools. This database is available on a webpage https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1D_sC7VUtQRuRcCgc9rROVU7ghrdiVAg&ll=-2.458804534247277%2C154.35254980859378&z=6, providing a short description and pictures of some of the items, completed by Supplementary data. Thanks to this important record of entire objects, the author presents the different possibilities regarding hafting styles, blade orientations and attachment techniques. The combination of these different characteristics led the author to the introduction of a dynamic typology based on the concept of ‘morphospace’. Eight types have been so identified for the Asia Pacific region. The geographical distribution of these types is then presented and questioned, bringing also to the forefront some archaeological findings. An emphasis is made on New Guinea island where documentation is important. We can mention the emblematic work of Anne-Marie and Pierre Pétrequin (1993 and 2020) focused on West Papua, providing one of the most consulted books on stone axes by archaeologists. The worthy explanations tested to understand this repartition mobilize archaeological or linguistic data to hypothesise a three waves model of innovations in link with agricultural practices. A discussion on the correlation between material culture and language highlights in the background the need for interdisciplinary to deal finely with these interactions and linkages as has been effectively demonstrated elsewhere (Hermann and Walworth 2020). To conclude, the convergence between European Neolithic and New Guinea polished stone tools is demonstrated here through ‘morphospace’ comparisons. Thanks to this study, the polished stone tools come alive more than any European archaeological context would allow. The population dynamics investigated through these tools are directly relevant to current scientific issues concerning material culture. This example of convergent evolution is therefore an important key to considering this article as a source of inspiration for the archaeological community. References Buckley C. (2023). Hafted Stone and Shell Tools in the Asia Pacific Region, PsyArXiv, v.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2 De Labriffe A., Thirault E. dir. (2012). Produire des haches au Néolithique, de la matière première à l’abandon, Paris, Société préhistorique française (Séances de la Société préhistorique française, 1). Hermann A., Walworth M. (2020). Approche interdisciplinaire des échanges interculturels et de l’intégration des communautés polynésiennes dans le centre du Vanuatu, Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 151, 239-262. https://doi-org.docelec.u-bordeaux.fr/10.4000/jso.11963 Masclans Latorre A. (2020). Use-wear Analyses of Polished and Bevelled Stone Artefacts during the Sepulcres de Fossa/Pit Burials Horizon (NE Iberia, c. 4000–3400 cal B.C.), Oxford, BAR Publishing (BAR International Series 2972). Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (1993). Écologie d'un outil : la hache de pierre en Irian Jaya (Indonésie), Paris, CNRS Editions. Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (2020). Ecology of a Tool: The ground stone axes of Irian Jaya (Indonesia). Oxbow Books. | Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific Region | Christopher Buckley | <p>Hafted stone tools fell into disuse in the Pacific region in the 19th and 20th centuries. Before this occurred, examples of tools were collected by early travelers, explorers and tourists. These objects, which now reside in ethnographic collect... |  | Asia, Conservation/Museum studies, Lithic technology, Neolithic, Oceania | Solène Denis | 2022-11-09 18:37:08 | View | |

11 Oct 2023

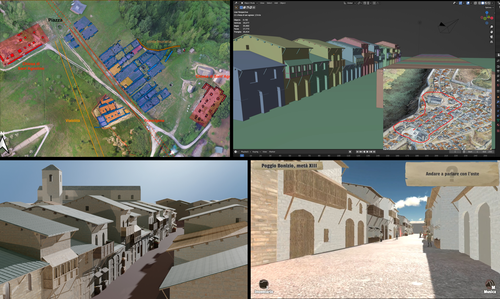

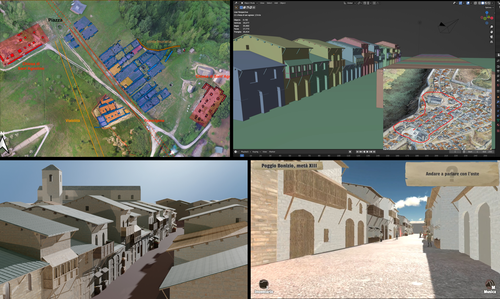

Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill ProjectSamanta Mariotti https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563Gamification of an archaeological park: The Living Hill Project as work-in-progressRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (2023) describes The Living Hill project dedicated to the archaeological park and fortress of Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi, Italy. The project is a collaboration between the Poggibonsi excavation and Entertainment Games App, Ltd. From the start, the project focused on the question of the intended audience rather than on the used technology. It was therefore planned to involve the audience in the creation of the game itself, which was not possible after all due to the covid pandemic. Nevertheless, the game aimed towards a visit experience as close as possible to reality to offer an educational tool through the video game, as it offers more periods than the medieval period showcased in the archaeological park itself. The game mechanics differ from a walking simulator, or a virtual tour and the player is tasked with returning three lost objects in the virtual game. While the medieval level was based on a 3D scan of the archaeological park, the other two levels were reconstructed based on archaeological material. Currently, only a PC version is working, but the team works on a mobile version as well and teased the possibility that the source code will be made available open source. Lastly, the team also evaluated the game and its perception through surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Although the surveys were only based on 21 persons, the results came back positive overall. The paper is well-written and follows a consistent structure. The authors clearly define the goals and setting of the project and how they developed and evaluated the game. Although it has be criticized that the game is not playable yet and the size of the questionnaire is too low, the authors clearly replied to the reviews and clarified the situation on both matters. They also attended to nearly all of the reviewers demands and answered them concisely in their response. In my personal opinion, I can fully recommend this paper for publication. For future works, it is recommended that the authors enlarge their audience for the quesstionaire in order to get more representative results. It it also recommended to make the game available as soon as possible also outside of the archaeological park. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their concise and constructive criticism to this paper as well as for their time. References Mariotti, Samanta. (2023) Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project, Zenodo, 8302563, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563 | Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of *The Living Hill* Project | Samanta Mariotti | <p>Video games are now recognised as a valuable tool for disseminating and enhancing archaeological heritage. In Italy, the recent institutionalisation of Public Archaeology programs and incentives for digital innovation has resulted in a prolifer... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Europe, Medieval, Post-medieval | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-30 20:25:32 | View | |

02 Apr 2024

The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial CommunityAlphaeus Lien-Talks https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307882A nice project looking at under-represented demographicRecommended by Alexis Pantos based on reviews by Catriona Cooper and Steinar Kristensen based on reviews by Catriona Cooper and Steinar Kristensen

The paper by A. Lien-Talks [1] presents a small project looking at the use of crowd sourced data collection and particpatory GIS. In particular it looks at the potential of these tools in response to socially disruptive and isolating events such as the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the potential role of digitially mediated heritage initiatives in tackling some of the challenges of changing demographics and life styles. The types of technologies employed are relatively mature, the project identifies potential for such approaches to be used within the local-history/local community settings, though is also a reminer that depsite the much broader adoption of technology within all areas of society than even a few years ago many barriers still remain. While the the sample size and data collected in the project is relatively modest, the focus on empathy toward the intended audiences from the design process, as well as some of the qualitative feedback reported serve as a reminder that participatory, or crowd-sourced data collection initiatives in heritage can, and perhaps should place potential social benefit before data-acquisition of objectives. The project also presents a demographic that is not often represented within the literature and the publication and as such the publication of the article represents a meaningful contribution to ongoing discussions of the role heritage and digitally mediated community archaeology can play a role in developing our societies. References [1] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial Community. Zenodo, 8307882, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307882 | The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial Community | Alphaeus Lien-Talks | <p>Background:<br>As the world becomes increasingly digital, so too must the way in which archaeologists engage with the public. This was particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic, and many outreach and engagement efforts began to move o... |  | Computational archaeology | Alexis Pantos | 2023-09-01 11:25:54 | View | |

02 Dec 2023

Research perspectives and their influence for typologiesEnrico Giannichedda https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7322855Complexity and Purpose – A Pragmatic Approach to the Diversity of Archaeological Classificatory Practice and TypologyRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Ulrich Veit, Martin Hinz, Artur Ribeiro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ulrich Veit, Martin Hinz, Artur Ribeiro and 1 anonymous reviewer

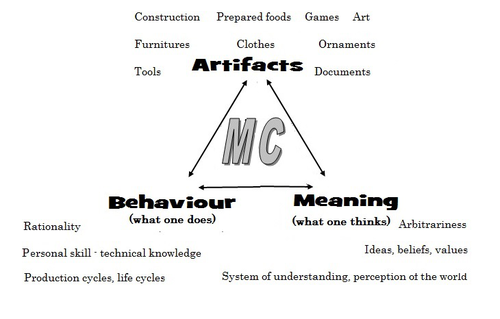

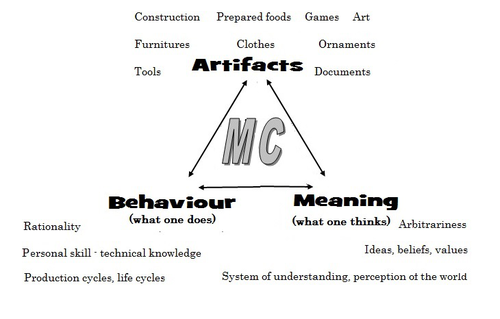

“Research perspectives and their influence for typologies” by E. Giannichedda (1) is a contribution to the upcoming volume on the role of typology and type-thinking in current archaeological theory and praxis edited by the recommenders. Taking a decidedly Italian perspective on classificatory practice grounded in what the author dubs the “history of material culture”, Giannichedda offers an inventory of six divergent but overall complementary modes of ordering archaeological material: i) chrono-typological and culture-historical, ii) techno-anthropological, iii) social, iv) socio-economic and v) cognitive. These various lenses broadly align with similarly labeled perspectives on the archaeological record more generally. According to the author, they lend themselves to different ways of identifying and using types in archaeological work. Importantly, Giannichedda reminds us that no ordering practice is a neutral act and typologies should not be devised for their own sake but because we have specific epistemic interests. Even though this view is certainly not shared by everyone involved in the broader debate on the purpose and goal of systematics, classification, typology or archaeological taxonomy (2–4), the paper emphatically defends the long-standing idea that ordering practices are not suitable to elucidate the structure and composition of reality but instead devise tools to answer certain questions or help investigate certain dimensions of complex past realities. This position considers typologies as conceptual prosthetics of knowing, a view that broadly resonates with what is referred to as epistemic instrumentalism in the philosophy of science (5, 6). Types and type-work should accordingly reflect well-defined means-end relationships. Based on the recognition of archaeology as part of an integrated “history of material culture” rooted in a blend of continental and Anglophone theories, Giannichedda argues that type-work should pay attention to relevant relations between various artefacts in a given historical context that help further historical understanding. Classificatory practice in archaeology – the ordering of artefactual materials according to properties – must thus proceed with the goal of multifaceted “historical reconstruction in mind”. It should serve this reconstruction, and not the other way around. By drawing on the example of a Medieval nunnery in the Piedmont region of northwestern Italy, Giannichedda explores how different goals of classification and typo-praxis (linked to i-v; see above) foreground different aspects, features, and relations of archaeological materials and as such allow to pinpoint and examine different constellations of archaeological objects. He argues that archaeological typo-praxis, for this reason, should almost never concern itself with isolated artefacts but should take into account broader historical assemblages of artefacts. This does not necessarily mean to pay equal attention to all available artefacts and materials, however. To the contrary, in many cases, it is necessary to recognize that some artefacts and some features are more important than others as anchors grouping materials and establishing relations with other objects. An example are so-called ‘barometer objects’ (7) or unique pieces which often have exceptional informational value but can easily be overlooked when only shared features are taken into consideration. As Giannichedda reminds us, considering all objects and properties equally is also a normative decision and does not render ordering less subjective. The archaeological analysis of types should therefore always be complemented by an examination of variants, even if some of these variants are idiosyncratic or even unique. A type, then, may be difficult to define universally. In total, “Research perspectives and their influence for typologies” emphasizes the need for “elastic” and “flexible” approaches to archaeological types and typologies in order to effectively respond to the manifold research interests cultivated by archaeologists as well as the many and complex past realities they face. Complexity is taken here to indicate that no single research perspective and associated mode of ordering can adequately capture the dimensionality and richness of these past realities and we can therefore only benefit from multiple co-existing ways of grouping and relating archaeological artefacts. Different logics of grouping may simply reveal different aspects of these realities. As such, Giannichedda’s proposal can be read as a formulation of the now classic pluralism thesis (8–11) – that only a plurality of ways of ordering and interrelating artefacts can unlock the full suite of relationships within historical assemblages archaeologists are interested in.

Bibliography 1. Giannichedda, E. (2023). Research perspectives and their influence for typologies, Zenodo, 7322855, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7322855 2. Dunnell, R. C. (2002). Systematics in Prehistory, Illustrated Edition (The Blackburn Press, 2002). 3. Reynolds, N. and Riede, F. (2019). House of cards: cultural taxonomy and the study of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Antiquity 93, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.49 4. Lyman, R. L. (2021). On the Importance of Systematics to Archaeological Research: the Covariation of Typological Diversity and Morphological Disparity. J Paleo Arch 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00077-6 5. Van Fraassen, B. C. (2002). The empirical stance (Yale University Press). 6. Stanford, P. K. (2006). Exceeding Our Grasp: Science, History, and the Problem of Unconceived Alternatives (Oxford University Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/0195174089.001.0001 7. Radohs, L. (2023). Urban elite culture: a methodological study of aristocracy and civic elites in sea-trading towns of the southwestern Baltic (12th-14th c.) (Böhlau). 8. Kellert, S. H., Longino, H. E. and Waters, C. K. (2006). Scientific pluralism (University of Minnesota Press). 9. Cat, J. (2012). Essay Review: Scientific Pluralism. Philosophy of Science 79, 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/664747 10. Chang, H. (2012). Is Water H2O?: Evidence, Realism and Pluralism (Springer Netherlands). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3932-1 11. Wylie, A. (2015). “A plurality of pluralisms: Collaborative practice in archaeology” in Objectivity in Science, (Springer), pp. 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14349-1_10

| Research perspectives and their influence for typologies | Enrico Giannichedda | <p>This contribution opens with a brief reflection on theoretical archaeology and practical material classification activities. Following this, the various questions that can be asked of artefacts to be classified will be briefly addressed. Questi... |  | Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2022-11-10 20:14:52 | View | |

28 Feb 2021

A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic AgeAlain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/7dq3b/Open data on beads, pendants, blanks from the Ceramic Age CaribbeanRecommended by Ben Marwick based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang

The paper 'A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age' by Queffelec et al. [1] presents a description of a dataset of nearly 5000 lapidary artefacts from over 100 sites. The data are dominated by beads and pendants, which are mostly made from Diorite, Turquoise, Carnelian, Amethyst, and Serpentine. The raw material data is especially valuable as many of these are not locally available on the island. This holds great potential for exchange network analysis. The data may be especially useful for investigating one of the fundamental questions of this region: whether the Cedrosan and Huecan are separate, little related developments, with different origins, or variants or a single tradition [2]. In addition to metric and technological details about the artefacts, the data include a variety of locational details, including coordinates, distance to coast, and altitude. This enables many opportunities for future spatial analysis and geostatistical modelling to understand human behaviours relating to ornament production, use, and discard. I recommend the authors make a minor revision to Table 1 (spatial coverage of the dataset) to make the column with the citations conform to the same citation style used in the rest of the text. I warmly commend the authors for making transparency and reproducibility a priority when preparing their manuscript. Their use of the R Markdown format for writing reproducible, dynamic documents [3] is highly impressive. This is an excellent example for others in the international archaeological science community to follow. The paper is especially useful for researchers who are new to R and R Markdown because of the elegant and accessible way the authors document their research here. [1] Queffelec, A., Fouéré, P. and Caverne, J.-B. 2021. A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age. SocArXiv, 7dq3b, ver. 4 Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/7dq3b [2] Reed, J. A. and Petersen, J. B. 2001. A comparison of Huecan and Cedrosan Saladoid ceramics at the Trants site, Montserrat. In Proceedings of the XVIIIth International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology (pp. 253-267). [3] Marwick, B. 2017. Computational Reproducibility in Archaeological Research: Basic Principles and a Case Study of Their Implementation. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24, 424–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-015-9272-9 | A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age | Alain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne | <p>Lapidary artifacts show an impressive abundance and diversity during the Ceramic period in the Caribbean islands, especially at the beginning of this period. Most of the raw materials used in this production do not exist naturally on the island... |  | Neolithic, North America, Raw materials, South America, Spatial analysis, Symbolic behaviours | Ben Marwick | 2020-11-13 23:52:34 | View | |

20 Jul 2022

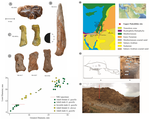

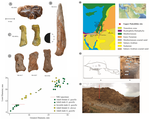

Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, IsraelNimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4New zooarchaeological data from the Upper Palaeolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2, IsraelRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio

The Levantine Corridor is considered a crossing point to Eurasia and one of the main areas for detecting population flows (and their associated cultural and economic changes) during the Pleistocene. This area could have been closed during the most arid periods, giving rise to processes of population isolation between Africa and Eurasia and intermittent contact between Eurasian human communities [1,2]. Zooarchaeological studies of the early Upper Palaeolithic assemblages constitute an important source of knowledge about human subsistence, making them central to the debate on modern behaviour. The Early Upper Palaeolithic sequence in the Levant includes two cultural entities – the Early Ahmarian and the Levantine Aurignacian. This latter is dated to 39-33 ka and is considered a local adaptation of the European Aurignacian techno-complex. In this work, the authors present a zooarchaeological study of the Nahal Rahaf 2 (ca. 35 ka) archaeological site in the southern Judean Desert in Israel [3]. Zooarchaeological data from the early Upper Paleolithic desert regions of the southern Levant are not common due to preservation problems of non-lithic finds. In the case of Nahal Rahaf 2, recent excavation seasons brought to light a stratigraphical sequence composed of very well-preserved archaeological surfaces attributed to the 'Arkov-Divshon' cultural entity, which is associated with the Levantine Aurignacian. This study shows age-specific caprine (Capra cf. Capra ibex) hunting on prime adults and a generalized procurement of gazelles (Gazella cf. Gazella gazella), which seem to have been selectively transported to the site and processed for within-bone nutrients. An interesting point to note is that the proportion of goats increases along the stratigraphic sequence, which suggests to the authors a specialization in the economy over time that is inversely related to the occupational intensity of use of the site. It is also noteworthy that the materials represent a large sample compared to previous studies from the Upper Paleolithic of the Judean Desert and Negev. In summary, this manuscript contributes significantly to the study of both the palaeoenvironment and human subsistence strategies in the Upper Palaeolithic and provides another important reference point for evaluating human hunting adaptations in the arid regions of the southern Levant. References [1] Bermúdez de Castro, J.-L., Martinon-Torres, M. (2013). A new model for the evolution of the human pleistocene populations of Europe. Quaternary Int. 295, 102-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.036 [2] Bar-Yosef, O., Belfer-Cohen, A. (2010). The Levantine Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic. In Garcea, E.A.A. (Ed), South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples Between 130,000 and 10,000 Years Ago. Oxbow Books, pp. 144-167. [3] Marom, N., Gnezdilov, D. L., Shafir, R., Barzilai, O. and Shemer, M. (2022). Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel. BioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492258, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4 | Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel | Nimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer | <p>Nahal Rahaf 2 (NR2) is an Early Upper Paleolithic (ca. 35 kya) rock shelter in the southern Judean Desert in Israel. Two excavation seasons in 2019 and 2020 revealed a stratigraphical sequence composed of intact archaeological surfaces attribut... |  | Upper Palaeolithic, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Joana Gabucio | 2022-05-19 06:16:47 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer