Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

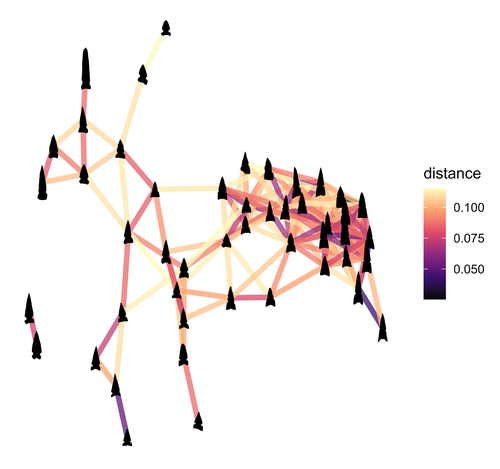

28 Aug 2023

Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Projectile Points from the Southwest United StatesRobert J. Bischoff https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/a6wjc2D Geometric Morphometrics of Projectile Points from the Southwestern United StatesRecommended by Adrian L. Burke based on reviews by James Conolly and 1 anonymous reviewerBischoff (2023) is a significant contribution to the growing field of geometric morphometric analysis in stone tool analysis. The subject is projectile points from the southwestern United States. Projectile point typologies or systematics remain an important part of North American archaeology, and in fact these typologies continue to be used primarily as cultural-historical markers. This article looks at projectile point types using a 2D image geometric morphometric analysis as a way of both improving on projectile point types but also testing if these types are in fact based in measurable reality. A total of 164 point outlines are analyzed using Elliptical Fourier, semilandmark and landmark analyses. The author also uses a network analysis to look at possible relationships between projectile point morphologies in space. This is a clever way of working around the predefined distributions of projectile point types, some of which are over 100 years old. Because of the dynamic nature of stone tools in terms of their use, reworking and reuse, this article can also provide solutions for studying the dynamic nature of stone tools. This article therefore also has a wide applicability to other stone tool analyses. Reference Bischoff, R. J. (2023) Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Projectile Points from the Southwest United States, SocArXiv, a6wjc, ver. 8 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/a6wjc | Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Projectile Points from the Southwest United States | Robert J. Bischoff | <p style="text-align: justify;">Traditional analyses of projectile points often use visual identification, the presence or absence of discrete characteristics, or linear measurements and angles to classify points into distinct types. Geometric mor... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology, Lithic technology, North America | Adrian L. Burke | 2022-12-18 03:38:14 | View | |

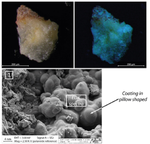

17 Jun 2022

Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France)Marine Quiers, Claire Chanteraud, Andréa Maris-Froelich, Émilie Chalmin-Aljanabi, Stéphane Jaillet, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Pairis, Yves Perrette, Hélène Salomon, Julien Monney https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03383193v5New method for the in situ detection and characterisation of amorphous silica in rock art contextsRecommended by Aitor Ruiz-Redondo based on reviews by Alain Queffelec, Laure Dayet and 1 anonymous reviewerSilica coating developed in cave art walls had an impact in the preservation of the paintings themselves. Despite it still exists a controversy about whether or not the effects contribute to the preservation of the artworks; it is evident that identifying these silica coatings would have an impact to assess the taphonomy of the walls and the paintings preserved on them. Unfortunately, current techniques -especially non-invasive ones- can hardly address amorphous silica characterisation. Thus, its presence is often detected on laboratory observations such as SEM or XRD analyses. In the paper “Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context - Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France)”, Quiers and collaborators propose a new method for the in situ detection and characterisation of amorphous silica in a rock art context based on UV laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) and UV illumination [1]. The results from both methods presented by the authors are convincing for the detection of U-silica mineralisation (U-opal in the specific case of study presented). This would allow access to a fast and cheap method to identify this kind of formations in situ in decorated caves. Beyond the relationship between opal coating and the preservation of the rock art, the detection of silica mineralisation can have further implications. First, it can help to define spot for sampling for pigment compositions, as well as reconstruct the chronology of the natural history of the caves and its relation with the human frequentation and activities. In conclusion, I am glad to recommend this original research, which offers a new approach to the identification of geological processes that affect -and can be linked with- the Palaeolithic cave art. [1] Quiers, M., Chanteraud, C., Maris-Froelich, A., Chalmin-Aljanabi, E., Jaillet, S., Noûs, C., Pairis, S., Perrette, Y., Salomon, H., Monney, J. (2022) Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France). HAL, hal-03383193, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03383193v5 | Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France) | Marine Quiers, Claire Chanteraud, Andréa Maris-Froelich, Émilie Chalmin-Aljanabi, Stéphane Jaillet, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Pairis, Yves Perrette, Hélène Salomon, Julien Monney | <p style="text-align: justify;">Silica coatings development on rock art walls in Points Cave questions the analytical access to pictorial matter specificities (geochemistry and petrography) and the rock art conservation state in the context of pig... |  | Archaeometry, Europe, Rock art, Taphonomy, Upper Palaeolithic | Aitor Ruiz-Redondo | 2021-10-25 11:12:48 | View | |

19 Feb 2024

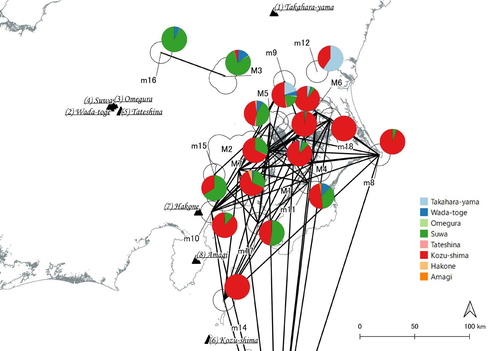

Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias ReductionFumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330Evaluating Methods for Reducing Sampling Bias in Network AnalysisRecommended by James Allison based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewer

In a recent article, Fumihiro Sakahira and Hiro'omi Tsumura (2023) used social network analysis methods to analyze change in obsidian trade networks in Japan throughout the 13,000-year-long Jomon period. In the paper recommended here (Sakahira and Tsumura 2024), Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction they revisit that data and describe additional analyses that confirm the robustness of their social network analysis. The data, analysis methods, and substantive conclusions of the two papers overlap; what this new paper adds is a detailed examination of the data and methods, including use of bootstrap analysis to demonstrate the reasonableness of the methods they used to group sites into clusters. Both papers begin with a large dataset of approximately 21,000 artifacts from more than 250 sites dating to various times throughout the Jomon period. The number of sites and artifacts, varying sample sizes from the sites, as well as the length of the Jomon period, make interpretation of the data challenging. To help make the data easier to interpret and reduce problems with small sample sizes from some sites, the authors assign each site to one of five sub-periods, then define spatial clusters of sites within each period using the DBSCAN algorithm. Sites with at least three other sites within 10 km are joined into clusters, while sites that lack enough close neighbors are left as isolates. Clusters or isolated sites with sample sizes smaller than 30 were dropped, and the remaining sites and clusters became the nodes in the networks formed for each period, using cosine similarities of obsidian assemblages to define the strength of ties between clusters and sites. The main substantive result of Sakahira and Tsumura’s analysis is the demonstration that, during the Middle Jomon period (5500-4500 cal BP), clusters and isolated sites were much more connected than before or after that period. This is largely due to extensive distribution of obsidian from the Kozu-shima source, located on a small island off the Japanese mainland. Before the Middle Jomon period, Kozu-shima obsidian was mostly found at sites near the coast, but during the Middle Jomon, a trade network developed that took Kozu-shima obsidian far inland. This ended after the Middle Jomon period, and obsidian networks were less densely connected in the late and last Jomon periods. The methods and conclusions are all previously published (Sakahira and Tsumura 2023). What Sakahira and Tsumura add in Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction are: · an examination of the distribution of cosine similarities between their clusters for each period · a similar evaluation of the cosine similarities within each cluster (and among the unclustered sites) for each period · bootstrap analyses of the mean cosine similarities and network densities for each time period These additional analyses demonstrate that the methods used to cluster sites are reasonable, and that the use of spatially defined clusters as nodes (rather than the individual sites within the clusters) works well as a way of reducing bias from small, unrepresentative samples. An alternative way to reduce that bias would be to simply drop small assemblages, but that would mean ignoring data that could usefully contribute to the analysis. The cosine similarities between clusters show patterns that make sense given the results of the network analysis. The Middle Jomon period has, on average, the highest cosine similarities between clusters, and most cluster pairs have high cosine similarities, consistent with the densely connected, spatially expansive network from that time period. A few cluster pairs in the Middle Jomon have low similarities, apparently representing comparisons including one of the few nodes on the margins on the network that had little or no obsidian from the Kozu-shima source. The other four time periods all show lower average inter-cluster similarities and many cluster pairs have either high or low similarities. This probably reflects the tendency for nearby clusters to have very similar obsidian assemblages to each other and for geographically distant clusters to have dissimilar obsidian assemblages. The pattern is consistent with the less densely connected networks and regionalization shown in the network graphs. Thinking about this pattern makes me want to see a plot of the geographic distances between the clusters against the cosine similarities. There must be a very strong correlation, but it would be interesting to know whether there are any cluster pairs with similarities that deviate markedly from what would be predicted by their geographic separation. The similarities within clusters are also interesting. For each time period, almost every cluster has a higher average (mean and median) within-cluster similarity than the similarity for unclustered sites, with only two exceptions. This is partial validation of the method used for creating the spatial clusters; sites within the clusters are at least more similar to each other than unclustered sites are, suggesting that grouping them this way was reasonable. Although Sakahira and Tsumura say little about it, most clusters show quite a wide range of similarities between the site pairs they contain; average within-cluster similarities are relatively high, but many pairs of sites in most clusters appear to have low similarities (the individual values are not reported, but the pattern is clear in boxplots for the first four periods). There may be value in further exploring the occurrence of low site-to-site similarities within clusters. How often are they caused by small sample sizes? Clusters are retained in the analysis if they have a total of at least 30 artifacts, but clusters may contain sites with even smaller sample sizes, and small samples likely account for many of the low similarity values between sites in the same cluster. But is distance between sites in a cluster also a factor? If the most distant sites within a spatially extensive cluster are dissimilar, subdividing the cluster would likely improve the results. Further exploration of these within-cluster site-to-site similarity values might be worth doing, perhaps by plotting the similarities against the size of the smallest sample included in the comparison, as well as by plotting the cosine similarity against the distance between sites. Any low similarity values not attributable to small sample sizes or geographic distance would surely be worth investigating further. Sakahira and Tsumura also use a bootstrap analysis to simulate, for each time period, mean cosine similarities between clusters and between site pairs without clustering. They also simulate the network density for each time period before and after clustering. These analyses show that, almost always, mean simulated cosine similarities and mean simulated network density are higher after clustering than before. The simulated mean values also match the actual mean values better after clustering than before. This improved match to actual values when the sites are clustered for the bootstrap reinforces the argument that clustering the sites for the network analysis was a reasonable result. The strength of this paper is that Sakahira and Tsumura return to reevaluate their previously published work, which demonstrated strong patterns through time in the nature and extent of Jomon obsidian trade networks. In the current paper they present further analyses demonstrating that several of their methodological decisions were reasonable and their results are robust. The specific clusters formed with the DBSCAN algorithm may or may not be optimal (which would be unreasonable to expect), but the authors present analyses showing that using spatial clusters does improve their network analysis. Clustering reduces problems with small sample sizes from individual sites and simplifies the network graphs by reducing the number of nodes, which makes the results easier to interpret. Reference Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2023). Tipping Points of Ancient Japanese Jomon Trade Networks from Social Network Analyses of Obsidian Artifacts. Frontiers in Physics 10:1015870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.1015870 Sakahira, F. and Tsumura, H. (2024). Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction, Zenodo, 10057602, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7969330 | Social Network Analysis of Ancient Japanese Obsidian Artifacts Reflecting Sampling Bias Reduction | Fumihiro Sakahira, Hiro’omi Tsumura | <p>This study aims to investigate the dynamics of obsidian trade networks during the Jomon period (approximately 15,000 to 2,400 years ago), the hunting and gathering era in Japan. To improve regional representation and reduce the distortions caus... |  | Asia, Computational archaeology | James Allison | Thegn Ladefoged, Matthew Peeples | 2023-05-28 05:51:12 | View |

21 Mar 2023

Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific RegionChristopher Buckley https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2From Polished Stone Tools to Population Dynamics: Ethnographic Archives as InsightsRecommended by Solène Denis based on reviews by Adrian L. Burke and 1 anonymous reviewerMost archaeological contexts provide objects without organic materials making them quite silent regarding their hafting techniques and use. This is especially true for the polished stone tools that only thanks to a few discoveries in a wet environment, we can obtain some insights regarding their hafting techniques. Use-wear analysis can also be of some support to get a better picture of these artefacts (e.g. Masclans Latorre 2020), whose typology testifies to an important diversity in European Neolithic contexts that sometimes are well-documented from the chaîne opératoire perspective (see De Labriffe and Thirault dir. 2012). The study offered by Chris Buckley (2023) constitutes an important contribution to animating these tools. His work relies on the Asia Pacific region, where he gathered data and mapped more than 300 ethnographic hafted stone and shell tools. This database is available on a webpage https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1D_sC7VUtQRuRcCgc9rROVU7ghrdiVAg&ll=-2.458804534247277%2C154.35254980859378&z=6, providing a short description and pictures of some of the items, completed by Supplementary data. Thanks to this important record of entire objects, the author presents the different possibilities regarding hafting styles, blade orientations and attachment techniques. The combination of these different characteristics led the author to the introduction of a dynamic typology based on the concept of ‘morphospace’. Eight types have been so identified for the Asia Pacific region. The geographical distribution of these types is then presented and questioned, bringing also to the forefront some archaeological findings. An emphasis is made on New Guinea island where documentation is important. We can mention the emblematic work of Anne-Marie and Pierre Pétrequin (1993 and 2020) focused on West Papua, providing one of the most consulted books on stone axes by archaeologists. The worthy explanations tested to understand this repartition mobilize archaeological or linguistic data to hypothesise a three waves model of innovations in link with agricultural practices. A discussion on the correlation between material culture and language highlights in the background the need for interdisciplinary to deal finely with these interactions and linkages as has been effectively demonstrated elsewhere (Hermann and Walworth 2020). To conclude, the convergence between European Neolithic and New Guinea polished stone tools is demonstrated here through ‘morphospace’ comparisons. Thanks to this study, the polished stone tools come alive more than any European archaeological context would allow. The population dynamics investigated through these tools are directly relevant to current scientific issues concerning material culture. This example of convergent evolution is therefore an important key to considering this article as a source of inspiration for the archaeological community. References Buckley C. (2023). Hafted Stone and Shell Tools in the Asia Pacific Region, PsyArXiv, v.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2 De Labriffe A., Thirault E. dir. (2012). Produire des haches au Néolithique, de la matière première à l’abandon, Paris, Société préhistorique française (Séances de la Société préhistorique française, 1). Hermann A., Walworth M. (2020). Approche interdisciplinaire des échanges interculturels et de l’intégration des communautés polynésiennes dans le centre du Vanuatu, Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 151, 239-262. https://doi-org.docelec.u-bordeaux.fr/10.4000/jso.11963 Masclans Latorre A. (2020). Use-wear Analyses of Polished and Bevelled Stone Artefacts during the Sepulcres de Fossa/Pit Burials Horizon (NE Iberia, c. 4000–3400 cal B.C.), Oxford, BAR Publishing (BAR International Series 2972). Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (1993). Écologie d'un outil : la hache de pierre en Irian Jaya (Indonésie), Paris, CNRS Editions. Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (2020). Ecology of a Tool: The ground stone axes of Irian Jaya (Indonesia). Oxbow Books. | Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific Region | Christopher Buckley | <p>Hafted stone tools fell into disuse in the Pacific region in the 19th and 20th centuries. Before this occurred, examples of tools were collected by early travelers, explorers and tourists. These objects, which now reside in ethnographic collect... |  | Asia, Conservation/Museum studies, Lithic technology, Neolithic, Oceania | Solène Denis | 2022-11-09 18:37:08 | View | |

11 Jan 2022

Tektite geoarchaeology in mainland Southeast AsiaBen Marwick, Son Thanh Pham, Rachel Brewer, Li-Ying Wang https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/93fpaTektites as chronological markers: after careful geoarchaeological validation only!Recommended by Alain Queffelec and Shanti Pappu based on reviews by Sheila Mishra, Toshihiro Tada, Mike Morley and 1 anonymous reviewer and Shanti Pappu based on reviews by Sheila Mishra, Toshihiro Tada, Mike Morley and 1 anonymous reviewer

Tektites, a naturally occurring glass produced by major cosmic impacts and ejected at long distances, are known from five impacts worldwide [1]. The presence of this impact-generated glass, which can be dated in the same way as a volcanic rock, has been used to date archaeological sites in several regions of the world. This paper by Marwick and colleagues [2] reviews and adds new data on the use and misuse of this specific material as a chronological marker in Australia, East and Southeast Asia, where an impact dated to 0.78 Ma created and widely distributed tektites. This material, found in archaeological excavations in China, Laos, Thaïland, Australia, Borneo, and Vietnam, has been used to date layers containing lithic artifacts, sometimes creating a strong debate about the antiquity of the occupation and lithic production in certain regions. The review of existing data shows that geomorphological data and stratigraphic integrity can be questioned at many sites that have yielded tektites. The new data provided by this paper for five archaeological sites located in Vietnam confirm that many deposits containing tektites are indeed lag deposits and that these artifacts, thus in secondary position, cannot be considered to date the layer. This study also emphasizes the general lack of other dating methods that would allow comparison with the tektite age. In the Vietnamese archaeological sites presented here, discrepancies between methods, and the presence of historical artifacts, confirm that the layers do not share similar age with the cosmic impact that created the tektites. Based on this review and these new results, and following previous propositions [3], Marwick and colleagues conclude that, if tektites can be used as chronological markers, one has to prove that they are in situ. They propose that geomorphological assessment of the archaeological layer as primary deposit must first be attained, in addition to several parameters of the tektites themselves (shape, size distribution, chemical composition). Large error can be made by using only tektites to date an archaeological layer, and this material should not be used solely due to risks of high overestimation of the age of the archaeological production. [1] Rochette, P., Beck, P., Bizzarro, M., Braucher, R., Cornec, J., Debaille, V., Devouard, B., Gattacceca, J., Jourdan, F., Moustard, F., Moynier, F., Nomade, S., Reynard, B. (2021). Impact glasses from Belize represent tektites from the Pleistocene Pantasma impact crater in Nicaragua. Communications Earth & Environment, 2(1), 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00155-1 [2] Marwick, B., Son, P. T., Brewer, R., Wang, L.-Y. (2022). Tektite geoarchaeology in mainland Southeast Asia. SocArXiv, 93fpa, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology, https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/93fpa. [3] Tada, T., Tada, R., Chansom, P., Songtham, W., Carling, P. A., Tajika, E. (2020). In Situ Occurrence of Muong Nong-Type Australasian Tektite Fragments from the Quaternary Deposits near Huai Om, Northeastern Thailand. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science 7(1), 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-020-00378-4 | Tektite geoarchaeology in mainland Southeast Asia | Ben Marwick, Son Thanh Pham, Rachel Brewer, Li-Ying Wang | <p>Tektites formed by an extraterrestrial impact event in Southeast Asia at 0.78 Ma have been found in geological contexts and archaeological sites throughout Australia, East and Southeast Asia. At some archaeological sites, especially in Bose Bas... |  | Asia, Geoarchaeology | Alain Queffelec | 2021-08-14 18:04:18 | View | |

08 Feb 2021

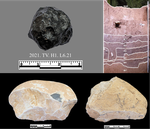

A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, ChinaLuc Doyon, Zhanyang Li, Hua Wang, Lila Geis, Francesco d’Errico https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/68xpzA step towards the challenging recognition of expedient bone toolsRecommended by Camille Daujeard based on reviews by Delphine Vettese, Jarod Hutson and 1 anonymous reviewerThis article by L. Doyon et al. [1] represents an important step to the recognition of bone expedient tools within archaeological faunal assemblages, and therefore deserves publication. In this work, the authors compare bone flakes and splinters experimentally obtained by percussion (hammerstone and anvil technique) with fossil ones coming from the Palaeolithic site of Lingjing in China. Their aim is to find some particularities to help distinguish the fossil bone fragments which were intentionally shaped, from others that result notably from marrow extraction. The presence of numerous (>6) contiguous flake scars and of a continuous size gradient between the lithics and the bone blanks used, appear to be two valuable criteria for identifying 56 bone elements of Lingjing as expedient bone tools. The latter are present alongside other bone tools used as retouchers [2]. Another important point underlined by this study is the co-occurrence of impact and flake scars among the experimentally broken specimens (~90%), while this association is seldom observed on archaeological ones. Thus, according to the authors, a low percentage of that co-occurrence could be also considered as a good indicator of the presence of intentionally shaped bone blanks. About the function of these expedient bone tools, the authors hypothesize that they were used for in situ butchering activities. However, future experimental investigations on this question of the function of these tools are expected, including an experimental use wear program. Finally, highlighting the presence of such a bone industry is of importance for a better understanding of the adaptive capacities and cultural practices of the past hominins. This work therefore invites all taphonomists to pay more attention to flake removal scars on bone elements, keeping in mind the possible existence of that type of bone tools. In fact, being able to distinguish between bone fragments due to marrow recovery and bone tools is still a persistent and important issue for all of us, but one that deserves great caution. [1] Doyon, L., Li, Z., Wang, H., Geis, L. and d'Errico, F. 2021. A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, China. Socarxiv, 68xpz, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/68xpz [2] Doyon, L., Li, Z., Li, H., and d’Errico, F. 2018. Discovery of circa 115,000-year-old bone retouchers at Lingjing, Henan, China. Plos one, 13(3), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194318. | A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, China | Luc Doyon, Zhanyang Li, Hua Wang, Lila Geis, Francesco d’Errico | <p>Activities attested since at least 2.6 Myr, such as stone knapping, marrow extraction, and woodworking may have allowed early hominins to recognize the technological potential of discarded skeletal remains and equipped them with a transferable ... |  | Asia, Middle Palaeolithic, Osseous industry, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Camille Daujeard | 2020-11-01 11:09:13 | View | |

01 Sep 2023

Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854))Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552A zooarchaeological perspective on testudine bones from Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Southeast AsiaRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta

The study of the evolution of the human diet has been a central theme in numerous archaeological and paleoanthropological investigations. By reconstructing diets, researchers gain deeper insights into how humans adapted to their environments. The analysis of animal bones plays a crucial role in extracting dietary information. Most studies involving ancient diets rely heavily on zooarchaeological examinations, which, due to their extensive history, have amassed a wealth of data. During the Pleistocene–Holocene periods, testudine bones have been commonly found in a multitude of sites. The use of turtles and tortoises as food sources appears to stretch back to the Early Pleistocene [1-4]. More importantly, these small animals play a more significant role within a broader debate. The exploitation of tortoises in the Mediterranean Basin has been examined through the lens of optimal foraging theory and diet breadth models (e.g. [5-10]). According to the diet breadth model, resources are incorporated into diets based on their ranking and influenced by factors such as net return, which in turn depends on caloric value and search/handling costs [11]. Within these theoretical frameworks, tortoises hold a significant position. Their small size and sluggish movement require minimal effort and relatively simple technology for procurement and processing. This aligns with optimal foraging models in which the low handling costs of slow-moving prey compensate for their small size [5-6,9]. Tortoises also offer distinct advantages. They can be easily transported and kept alive, thereby maintaining freshness for deferred consumption [12-14]. For example, historical accounts suggest that Mexican traders recognised tortoises as portable and storable sources of protein and water [15]. Furthermore, tortoises provide non-edible resources, such as shells, which can serve as containers. This possibility has been discussed in the context of Kebara Cave [16] and noted in ethnographic and historical records (e.g. [12]). However, despite these advantages, their slow growth rate might have rendered intensive long-term predation unsustainable. While tortoises are well-documented in the Southeast Asian archaeological record, zooarchaeological analyses in this region have been limited, particularly concerning prehistoric hunter-gatherer populations that may have relied extensively on inland chelonian taxa. With the present paper Bochaton et al. [17] aim to bridge this gap by conducting an exhaustive zooarchaeological analysis of turtle bone specimens from four Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Thailand and Cambodia. These assemblages span from the Late Pleistocene to the first half of the Holocene. The authors focus on bones attributed to the yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata), which is the most prevalent taxon in the assemblages. The research include osteometric equations to estimate carapace size and explore population structures across various sites. The objective is to uncover human tortoise exploitation strategies in the region, and the results reveal consistent subsistence behaviours across diverse locations, even amidst varying environmental conditions. These final proposals suggest the possibility of cultural similarities across different periods and regions in continental Southeast Asia. In summary, this paper [17] represents a significant advancement in the realm of zooarchaeological investigations of small prey within prehistoric communities in the region. While certain approaches and issues may require further refinement, they serve as a comprehensive and commendable foundation for assessing human hunting adaptations.

References [1] Hartman, G., 2004. Long-term continuity of a freshwater turtle (Mauremys caspica rivulata) population in the northern Jordan Valley and its paleoenvironmental implications. In: Goren-Inbar, N., Speth, J.D. (Eds.), Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 61-74. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dtct.11 [2] Alperson-Afil, N., Sharon, G., Kislev, M., Melamed, Y., Zohar, I., Ashkenazi, R., Biton, R., Werker, E., Hartman, G., Feibel, C., Goren-Inbar, N., 2009. Spatial organization of hominin activities at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. Science 326, 1677-1680. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180695 [3] Archer, W., Braun, D.R., Harris, J.W., McCoy, J.T., Richmond, B.G., 2014. Early Pleistocene aquatic resource use in the Turkana Basin. J. Hum. Evol. 77, 74-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.02.012 [4] Blasco, R., Blain, H.A., Rosell, J., Carlos, D.J., Huguet, R., Rodríguez, J., Arsuaga, J.L., Bermúdez de Castro, J.M., Carbonell, E., 2011. Earliest evidence for human consumption of tortoises in the European Early Pleistocene from Sima del Elefante, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain. J. Hum. Evol. 11, 265-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.06.002 [5] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N., Surovell, T.A., Tchernov, E., Bar-Yosef, O., 1999. Palaeolithic growth pulses evidenced by small animal exploitation. Science 283, 190-194. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5399.190 [6] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., Surovell, T.A., 2000. The tortoise and the hare: small-game use, the Broad-Spectrum Revolution, and paleolithic demography. Curr. Anthropol. 41, 39-73. https://doi.org/10.1086/300102 [7] Stiner, M.C., 2001. Thirty years on the “Broad Spectrum Revolution” and paleolithic demography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 (13), 6993-6996. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.121176198 [8] Stiner, M.C., 2005. The Faunas of Hayonim Cave (Israel): a 200,000-Year Record of Paleolithic Diet. Demography and Society. American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 48. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge. [9] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., 2002. Approaches to prehistoric diet breadth, demography, and prey ranking systems in time and space. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 9, 181-214. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016530308865 [10] Blasco, R., Cochard, D., Colonese, A.C., Laroulandie, V., Meier, J., Morin, E., Rufà, A., Tassoni, L., Thompson, J.C. 2022. Small animal use by Neanderthals. In Romagnoli, F., Rivals, F., Benazzi, S. (eds.), Updating Neanderthals: Understanding Behavioral Complexity in the Late Middle Palaeolithic. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 123-143. ISBN 978-0-12-821428-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2019-0-03240-2 [11] Winterhalder, B., Smith, E.A., 2000. Analyzing adaptive strategies: human behavioural ecology at twenty-five. Evol. Anthropol. 9, 51-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(2000)9:2%3C51::aid-evan1%3E3.0.co;2-7 [12] Schneider, J.S., Everson, G.D., 1989. The Desert Tortoise (Xerobates agassizii) in the Prehistory of the Southwestern Great Basin and Adjacent areas. J. Calif. Gt. Basin Anthropol. 11, 175-202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825383 [13] Thompson, J.C., Henshilwood, C.S., 2014b. Nutritional values of tortoises relative to ungulates from the Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa: implications for foraging and social behaviour. J. Hum. Evol. 67, 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.010 [14] Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Smith, K.T., Maul, L.Ch., Sañudo, P., Barkai, R., Gopher, A. 2016. Tortoises as a Dietary Supplement: a view from the Middle Pleistocene site of Qesem Cave, Israel. Quat Sci Rev 133, 165-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.12.006 [15] Pepper, C., 1963. The truth about the tortoise. Desert Mag. 26, 10-11. [16] Speth, J.D., Tchernov, E., 2002. Middle Paleolithic tortoise use at Kebara Cave (Israel). J. Archaeol. Sci. 29, 471-483. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2001.0740 [17] Bochaton, C., Chantasri, S., Maneechote, M., Claude, J., Griggo, C., Naksri, W., Forestier, H., Sophady, H., Auertrakulvit, P., Bowonsachoti, J. and Zeitoun, V. (2023) Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed Tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854)), BioRXiv, 2023.04.27.538552 , ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552v3 | Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (*Indotestudo elongata* (Blyth, 1854)) | Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun | <p style="text-align: justify;">While non-marine turtles are almost ubiquitous in the archaeological record of Southeast Asia, their zooarchaeological examination has been inadequately pursued within this tropical region. This gap in research hind... |  | Asia, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Iratxe Boneta, Noel Amano | 2023-05-02 09:30:50 | View |

29 Aug 2023

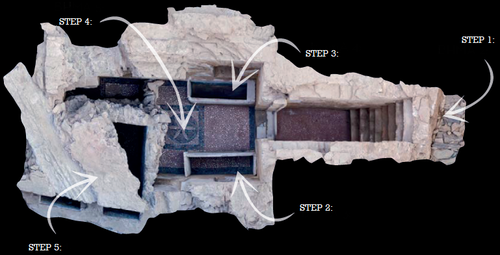

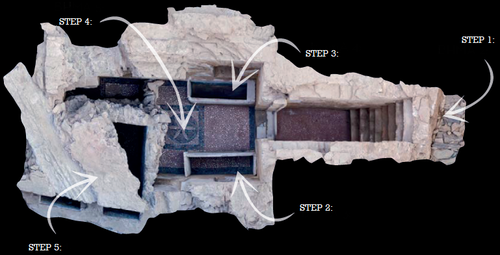

Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious GamesTsaknaki, Electra; Anastasovitis, Eleftherios; Georgiou, Georgia; Alagialoglou, Kleopatra; Mavrokostidou, Maria; Kartsiakli, Vasiliki; Aidonis, Asterios; Protopsalti, Tania; Nikolopoulos, Spiros; Kompatsiaris, Ioannis https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981323AR and VR Gamification as a proof-of-conceptRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Sophie C. Schmidt and Tine Rassalle based on reviews by Sophie C. Schmidt and Tine Rassalle

Tsaknaki et al. (2023) discuss a work-in-progress project in which the presentation of Cultural Heritage is communicated using Serious Games techniques in a story-centric immersive narration instead of an exhibit-centered presentation with the use of Gamification, Augmented and Virtual Reality technologies. In the introduction the authors present the project called ECHOES, in which knowledge about the past of Thessaloniki, Greece is planned to be processed as an immersive and interactive experience. After presenting related work and the methodology, the authors describe the proposed design of the Serious Game and close the article with a discussion and conclusions. The paper is interesting because it highlights an ongoing process in the realm of the visualization of Cultural Heritage (see for example Champion 2016). The process described by the authors on how to accomplish this by using Serious Games, Gamification, Augmented and Virtual Reality is promising, although still hypothetical as the project is ongoing. It remains to be seen if the proposed visuals and interactive elements will work in the way intended and offer users an immersive experience after all. A preliminary questionnaire already showed that most of the respondents were not familiar with these technologies (AR, VR) and in my experience these numbers only change slowly. One way to overcome the technological barrier however might be the gamification of the experience, which the authors are planning to implement. I decided to recommend this article based on the remarks of the two reviewers, which the authors implemented perfectly, as well as my own evaluation of the paper. Although still in progress it seems worthwhile to have this article as a basis for discussion and comparison to similar projects. However, the article did not mention the possible longevity of data and in which ways the usability of the Serious Game will be secured for long-term storage. One eminent problem in these endeavors is, that we can read about these projects, but never find them anywhere to test them ourselves (see for example Gabellone et al. 2016). It is my intention with this review and the recommendation, that the ECHOES project will find a solution for this problem and that we are not only able to read this (and forthcoming) article(s) about the ECHOES project, but also play the Serious Game they are proposing in the near and distant future. References

Gabellone, Francesco, Antonio Lanorte, Nicola Masini, und Rosa Lasaponara. 2016. „From Remote Sensing to a Serious Game: Digital Reconstruction of an Abandoned Medieval Village in Southern Italy“. Journal of Cultural Heritage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.01.012 Tsaknaki, Electra, Anastasovitis, Eleftherios, Georgiou, Georgia, Alagialoglou, Kleopatra, Mavrokostidou, Maria, Kartsiakli, Vasiliki, Aidonis, Asterios, Protopsalti, Tania, Nikolopoulos, Spiros, and Kompatsiaris, Ioannis. (2023). Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious Games, Zenodo, 7981323, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981323 | Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious Games | Tsaknaki, Electra; Anastasovitis, Eleftherios; Georgiou, Georgia; Alagialoglou, Kleopatra; Mavrokostidou, Maria; Kartsiakli, Vasiliki; Aidonis, Asterios; Protopsalti, Tania; Nikolopoulos, Spiros; Kompatsiaris, Ioannis | <p>The main challenge of the current digital transition is to utilize computing media and cutting-edge technologyin a more meaningful way, which would make the archaeological and anthropological research outcomes relevant to a heterogeneous audien... |  | Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Europe | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-05-29 13:19:46 | View | |

14 Mar 2024

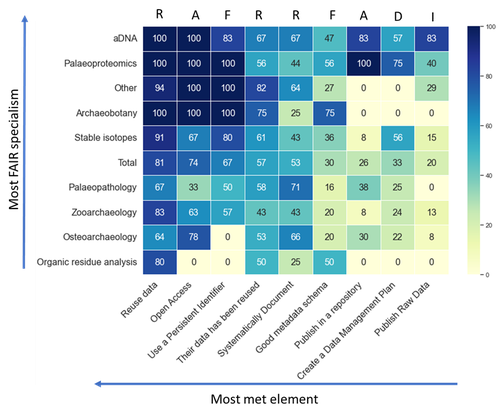

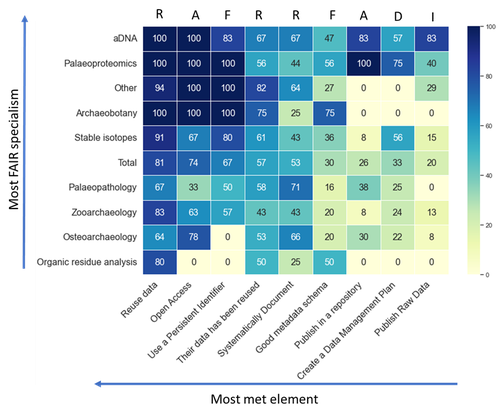

How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data ReusableLien-Talks, Alphaeus https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910FAIR data in bioarchaeology - where are we at?Recommended by Claudia Speciale based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers

The increasing reliance on digital and big data in archaeology is pushing the scientific community more and more to reconsider their storing and use [1, 2]. Furthermore, the openness and findability in the way these data are shared represent a key matter for the growth of the discipline, especially in the case of bioarchaeology and archaeological sciences [3]. In this paper, [4] the author presents the result of a survey targeted on UK bioarchaeologists and then extended worldwide. The paper maintains the structure of a report as it was intended for the conference it was part of (CAA 2023, Amsterdam) but it represents the first public outcome of an inquiry on the bioarchaeological scientific community. A reflection on ourselves and our own practices. Are all the disciplines adhering to the same policies? Do any bioarchaeologist use the same protocols and formats? Are there any differences in between the domains? Is the Needs Analysis fulfilling the questions? The results, obtained through an accurate screening to avoid distortions, are creating an intriguing picture on the current state of "fairness" and highlighting how Institutions' rules and policies can and should indicate the correct workflow to follow. In the end, the wide application of the FAIR principles will contribute significantly to the growth of the disciplines and to create an environment where the users are not just contributors, but primary beneficiaries of the system. [1] Huggett j. (2020). Is Big Digital Data Different? Towards a New Archaeological Paradigm, Journal of Field Archaeology, 45:sup1, S8-S17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2020.1713281 [2] Nicholson C., Kansa S., Gupta N. and Fernandez R. (2023). Will It Ever Be FAIR?: Making Archaeological Data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Advances in Archaeological Practice 11 (1): 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2022.40 [3] Plomp E., Stantis C., James H.F., Cheung C., Snoeck C., Kootker L., Kharobi A., Borges C., Reynaga D.K.M., Pospieszny Ł., Fulminante, F., Stevens, R., Alaica, A. K., Becker, A., de Rochefort, X. and Salesse, K. (2022). The IsoArcH initiative: Working towards an open and collaborative isotope data culture in bioarchaeology. Data in brief, 45, p.108595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2022.108595 [4] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable. Zenodo, 8139910, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910 | How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable | Lien-Talks, Alphaeus | <p>Bioarchaeology, which encompasses the study of ancient DNA, osteoarchaeology, paleopathology, palaeoproteomics, stable isotopes, and zooarchaeology, is generating an ever-increasing volume of data as a result of advancements in molecular biolog... |  | Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Zooarchaeology | Claudia Speciale | 2023-07-12 19:12:44 | View | |

02 Mar 2024

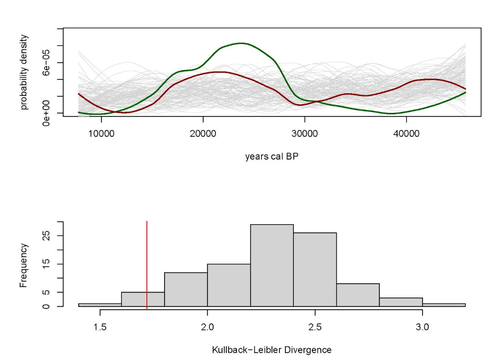

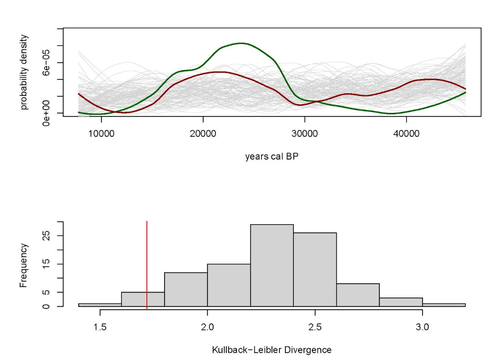

A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasetsNimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733A new approach to Predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer

Various biological systems have been subjected to mathematical modelling to enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions among different species. Among these models, the predator-prey model holds a significant position. Its relevance stems not only from its application in biology, where it largely governs the coexistence of diverse species in open ecosystems, but also from its utility in other domains. Predator-prey dynamics have long been a focal point in population ecology, yet access to real-world data is confined to relatively brief periods, typically less than a century. Studying predator-prey dynamics over extended periods presents challenges due to the limited availability of population data spanning more than a century. The most extensive dataset is the hare-lynx records from the Hudson Bay Company, documenting a century of fur trade [1]. However, other records are considerably shorter, usually spanning decades [2,3]. This constraint hampers our capacity to investigate predator-prey interactions over centennial or millennial scales. Marom and Wolkowski [4] propose here that leveraging regional radiocarbon databases offers a solution to this challenge, enabling the reconstruction of predator-prey population dynamics over extensive timeframes. To substantiate this proposition, they draw upon examples from Pleistocene Beringia and the Holocene Judean Desert. This approach is highly relevant and might provide insight into ecological processes occurring at a time scale beyond the limits of current ecological datasets. The methodological approach employed in this article proposes that the summed probability distribution (SPD) of predator radiocarbon dates, which reflects changes in population size, will demonstrate either more or less variation than anticipated from random sampling in a homogeneous distribution spanning the same timeframe. A deviation from randomness would imply a covariation between predator and prey populations. This basic hypothesis makes no assumptions about the frequency, mechanism, or cause of predator-prey interactions, as it is assumed that such aspects cannot be adequately tested with the available data. If validated, this hypothesis would offer initial support for the idea that long-term regional radiocarbon data contain signals of predator-prey interactions. This approach could justify the construction of larger datasets to facilitate a more comprehensive exploration of these signal structures.

References [1] Elton, C. and Nicholson, M., 1942. The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada. J. Anim. Ecol. 11, 215–244. [2] Gilg, O., Sittler, B. and Hanski, I., 2009. Climate change and cyclic predator-prey population dynamics in the high Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01927.x [3] Vucetich, J.A., Hebblewhite, M., Smith, D.W. and Peterson, R.O., 2011. Predicting prey population dynamics from kill rate, predation rate and predator-prey ratios in three wolf-ungulate systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01855.x [4] Marom, N. and Wolkowski, U. (2024). A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets, BioRxiv, 566733, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733 | A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets | Nimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski | <p>Predator-prey interactions have been a central theme in population ecology for the past century, but real-world data sets only exist for recent, relatively short (<100 years) time spans. This limits our ability to study centennial/millennial... |  | Bioarchaeology, Environmental archaeology, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | 2023-12-12 14:37:22 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer