Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * ▲ | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

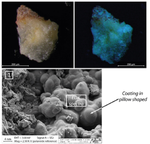

17 Jun 2022

Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France)Marine Quiers, Claire Chanteraud, Andréa Maris-Froelich, Émilie Chalmin-Aljanabi, Stéphane Jaillet, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Pairis, Yves Perrette, Hélène Salomon, Julien Monney https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03383193v5New method for the in situ detection and characterisation of amorphous silica in rock art contextsRecommended by Aitor Ruiz-Redondo based on reviews by Alain Queffelec, Laure Dayet and 1 anonymous reviewerSilica coating developed in cave art walls had an impact in the preservation of the paintings themselves. Despite it still exists a controversy about whether or not the effects contribute to the preservation of the artworks; it is evident that identifying these silica coatings would have an impact to assess the taphonomy of the walls and the paintings preserved on them. Unfortunately, current techniques -especially non-invasive ones- can hardly address amorphous silica characterisation. Thus, its presence is often detected on laboratory observations such as SEM or XRD analyses. In the paper “Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context - Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France)”, Quiers and collaborators propose a new method for the in situ detection and characterisation of amorphous silica in a rock art context based on UV laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) and UV illumination [1]. The results from both methods presented by the authors are convincing for the detection of U-silica mineralisation (U-opal in the specific case of study presented). This would allow access to a fast and cheap method to identify this kind of formations in situ in decorated caves. Beyond the relationship between opal coating and the preservation of the rock art, the detection of silica mineralisation can have further implications. First, it can help to define spot for sampling for pigment compositions, as well as reconstruct the chronology of the natural history of the caves and its relation with the human frequentation and activities. In conclusion, I am glad to recommend this original research, which offers a new approach to the identification of geological processes that affect -and can be linked with- the Palaeolithic cave art. [1] Quiers, M., Chanteraud, C., Maris-Froelich, A., Chalmin-Aljanabi, E., Jaillet, S., Noûs, C., Pairis, S., Perrette, Y., Salomon, H., Monney, J. (2022) Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France). HAL, hal-03383193, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03383193v5 | Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France) | Marine Quiers, Claire Chanteraud, Andréa Maris-Froelich, Émilie Chalmin-Aljanabi, Stéphane Jaillet, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Pairis, Yves Perrette, Hélène Salomon, Julien Monney | <p style="text-align: justify;">Silica coatings development on rock art walls in Points Cave questions the analytical access to pictorial matter specificities (geochemistry and petrography) and the rock art conservation state in the context of pig... |  | Archaeometry, Europe, Rock art, Taphonomy, Upper Palaeolithic | Aitor Ruiz-Redondo | 2021-10-25 11:12:48 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3DFlorian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269A valuable contribution to automated analysis of palaeolithic artefactsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper (Linsel/Bullenkamp/Mara 2024), the authors propose an automatic system for scar-ridge-pattern detection on palaeolithic artefacts based on Morse Theory. Scare-Ridge pattern recognition is a process that is usually done manually while creating a drawing of the object itself. Automatic systems to detect scars or ridges exist, but only a small amount of them is utilizing 3D data. In addition to the scar-ridges detection, the authors also experiment in automatically detecting the operational sequence, the temporal relation between scars and ridges. As a result, they can export a traditional drawing as well as graph models displaying the relationships between the scars and ridges. After an introduction to the project and the practice of documenting palaeolithic artefacts, the authors explain their procedure in automatising the analysis of scars and ridges as well as their temporal relation to each other on these artefacts. To illustrate the process, an open dataset of lithic artefacts from the Grotta di Fumane, Italy, was used and 62 artefacts selected. To establish a Ground Truth, the artefacts were first annotated manually. The authors then continue to explain in detail each step of the automated process that follows and the results obtained. In the second part of the paper, the results are presented. First the results of the segmentation process shows that the average percentage of correctly labelled vertices is over 91%, which is a remarkable result. The graph modelling however shows some more difficulties, which the authors are aware of. To enhance the process, the authors rightfully aim to include datasets of experimental archaeology in the future. They also aim to develop a way of detecting the operational sequence automatically and precisely. This paper has great potential as it showcases exactly what Digital and Computational Archaeology is about: The development of new digital methods to enhance the analysis of archaeological data. While this procedure is still in development, the authors were able to present a valuable contribution to the automatization of analytical archaeology. By creating a step towards the machine-readability of this data, they also open up the way to further steps in machine learning within Archaeology. BibliographyLinsel, F., Bullenkamp, J. P., and Mara, H. (2024). Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D, Zenodo, 8296269, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269 | Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D | Florian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara | <p>Motivated by the concept of combining the archaeological practice of creating lithic artifact drawings with the potential of 3D mesh data, our goal in this project is not only to analyze the shape at the artifact level, but also to enable a mor... | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Upper Palaeolithic | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-09-01 23:03:59 | View | ||

02 May 2024

Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard PracticesSharp Kayeleigh, Christofis Brooklyn, Eslamiat Hossein, Nepal Upesh, Osores Mendives Carlos https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307612A step forward in detecting small objects in UAV data for archaeological surveyingRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In this paper [1], the authors describe how they apply machine learning with YOLOv5 to classify visual data, aiming to enhance understanding of archaeological phenomena before conducting destructive fieldwork. Despite challenges, the integration of machine learning with remote sensing technology was seen as transformative, enabling precise recording of areas of interest and assessment of environmental risk factors. The paper discusses successes, failures, and future directions in machine learning research, emphasising the need for standardisation and integration of streamlined methods. The application of machine learning techniques facilitates non-destructive analysis of material culture records, improving conservation efforts and offering insights into both past and contemporary phenomena. While the initial use of YOLOv5 showed potential for consistent detection of archaeological features, further refinement and dataset enlargement are deemed necessary for broader application in non-destructive archaeological surveying. The authors advocate for the integration of machine learning tools in archaeological research to save time, resources, and promote ethical digital recording practices. They highlight the importance of standardised methodologies to enhance credibility and reproducibility, aiming to contribute to the ongoing dialogue in computational archaeology. Overall, I think this paper is a good step forward in detecting small objects in UAV data, and contains useful information for similar studies. The aim towards greater reproducibility and standardisation is of course shared more widely in the machine learning community, and this study is a good example of how to approach this. References [1] Sharp, K., Christofis, B., Eslamiat, H., Nepal, U. and Osores Mendives, C. (2024). Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard Practices. Zenodo, 8307612, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307612 | Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard Practices | Sharp Kayeleigh, Christofis Brooklyn, Eslamiat Hossein, Nepal Upesh, Osores Mendives Carlos | <p>Our collaborative work began in 2019 with the intent to overcome obstacles that had arisen from the inability to access curated artifact collections from remote locations. It was our specific aim to not only create digital twins of excavated ob... |  | Ceramics, Computational archaeology, Remote sensing, South America | Alex Brandsen | 2023-09-01 09:56:18 | View | |

07 May 2024

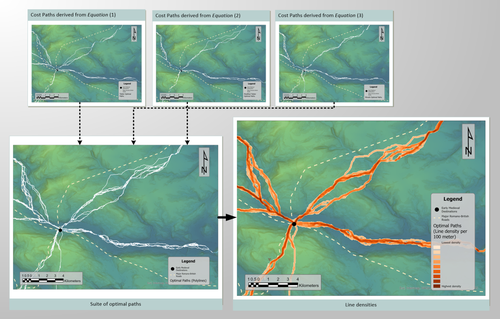

Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West EnglandWyatt Wilcox https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7999149Moving away from the ritual deposition: hoards from the Viking Age, Least Cost Paths and reused Roman RoadsRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Sam Leggett and Scott Madry based on reviews by Sam Leggett and Scott Madry

I had the pleasure of reading ‘Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England’ by Wyatt O. Wilcox (Wilcox 2024a). It is an honour to recommend this paper. The aim of this study is to research the relationship of 18 Viking Age hoards and their transport and depositional locations. This is studied in relation to the Roman road network and the landscape using least cost path analyses. Single finds from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (https://finds.org.uk/) are also incorporated in the study. The study deals with the distance of these Viking Age finds to these roads/least-cost-paths and the final interpretation moves away from ritual interpretation of these finds to a more mundane explanation. I feel that this could potentially open discussion also for hoards from other periods. While both reviewers (Sam Leggett and Scott Madry) presented various suggestions to improve the first submitted version of the paper, the author has done a tremendous job to improve the paper based on the comments and even beyond these comments. The author has also deposited the Jypiter-notebook online (Wilcox 2024b), showing that he is contributing to Open Science. The first version of the dataset has been improved and updated based on the comments by the reviewers and me, improving the reproducibility of the analyses. All in all, this paper has improved and I am very glad that I can recommend this for publication, and I’d like to do so with a sentence from the review by Sam Leggett: “this study has a lot of potential to be deployed across other regions, and time periods for similar purposes (Iron Age hoards for instance). And it will be of great interest to Viking Age experts interested in hoards, but also early medieval transport and travel.” References Wilcox, W. 2024a Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England. Zenodo, 7999149, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7999149 Wilcox, W. 2024b Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England (Supplemental Material). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11067607 | Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England | Wyatt Wilcox | <p>Discussions on Viking Age silver hoards in North West England have been dominated by analysis of the material compositions of the hoards. Despite a multi-century research legacy concerning the material composition of the Viking Age silver... |  | Europe, Landscape archaeology, Medieval, Spatial analysis | Ronald Visser | 2023-06-04 22:29:18 | View | |

03 Nov 2023

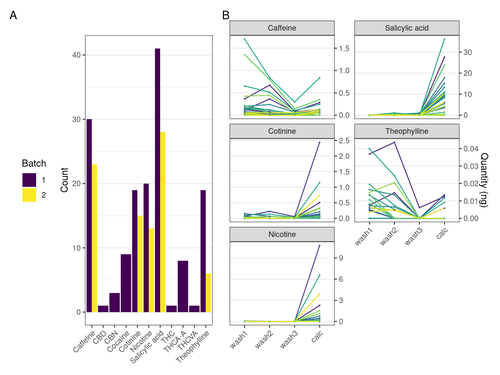

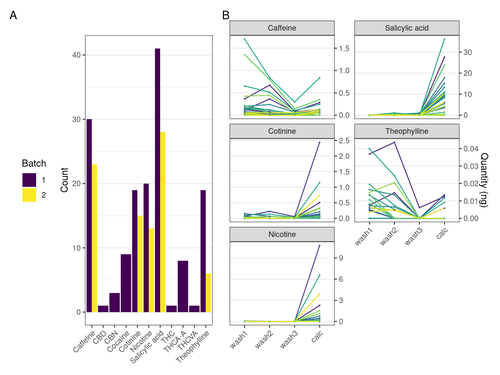

Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch populationBartholdy, Bjørn Peare; Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B.; Sørensen, Lambert K.; Casna, Maia; Hoogland, Menno; Historisch Genootschap Beemster; Henry, Amanda G. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7649150Detection of plant-derived compounds in XIXth c. Dutch dental calculusRecommended by Louise Le Meillour based on reviews by Mario Zimmerman and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Mario Zimmerman and 2 anonymous reviewers

The advent of biomolecular methods has certainly increased our overall comprehension of archaeological societies. One of the materials of choice to perform ancient DNA or proteomics analyses is dental calculus[1,2], a mineralised biofilm formed during the life of one individual. Research conducted in the past few decades has demonstrated the potential of dental calculus to retrieve information about past societies health[3–6], diet[7–11], and more recently, as a putative proxy for isotopic analyses[12].

Bartholdy et al. utilised the developed LC-MS/MS method to 41 buried individuals, most of them bearing pipe notches on their teeth, from the cemetery of the 19th rural settlement of Middenbeemster, the Netherlands. Along with dental calculus sampling and analysis, they undertook the skeletal and dental examination of all of the specimens in order to assess sex, age-at-death, and pathology on the two tissues. The results obtained on the dental calculus of the sampled individuals show probable consumption of tea, coffee and tobacco indicated by the detection of the various plant compounds and associated metabolites (caffeine, nicotine and salicylic acid, amongst others). The authors were able to place their results in perspective and propose several interpretations concerning the ingestion of plant-derived products, their survival in dental calculus and the importance of their findings for our overall comprehension of health and habits of the XIXth c. Dutch population. The paper is well-written and accessible to a non-specialist audience, maximising the impact of their study. I personally really enjoyed handling this manuscript that is not only a good piece of scientific literature but also a pleasant read, the reason why I warmly recommend this paper to be accessible through PCI Archaeology. References 1. Fagernäs, Z. and Warinner, C. (2023) Dental Calculus. in Handbook of Archaeological Sciences 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119592112.ch28 2. Wright, S. L., Dobney, K. & Weyrich, L. S. (2021) Advancing and refining archaeological dental calculus research using multiomic frameworks. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 7, 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2021.1882122 3. Fotakis, A. K. et al. (2020) Multi-omic detection of Mycobacterium leprae in archaeological human dental calculus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 375, 20190584. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0584 4. Warinner, C. et al. (2014) Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nat. Genet. 46, 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2906 5. Weyrich, L. S. et al. (2017) Neanderthal behaviour, diet, and disease inferred from ancient DNA in dental calculus. Nature 544, 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21674 6. Jersie-Christensen, R. R. et al. (2018) Quantitative metaproteomics of medieval dental calculus reveals individual oral health status. Nat. Commun. 9, 4744. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07148-3 7. Hendy, J. et al. (2018) Proteomic evidence of dietary sources in ancient dental calculus. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.0977 8. Wilkin, S. et al. (2020) Dairy pastoralism sustained eastern Eurasian steppe populations for 5,000 years. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1120-y 9. Bleasdale, M. et al. (2021) Ancient proteins provide evidence of dairy consumption in eastern Africa. Nat. Commun. 12, 632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20682-3 10. Warinner, C. et al. (2014) Direct evidence of milk consumption from ancient human dental calculus. Sci. Rep. 4, 7104. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07104 11. Buckley, S., Usai, D., Jakob, T., Radini, A. and Hardy, K. (2014) Dental Calculus Reveals Unique Insights into Food Items, Cooking and Plant Processing in Prehistoric Central Sudan. PLoS One 9, e100808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100808 12. Salazar-García, D. C., Warinner, C., Eerkens, J. W. and Henry, A. G. (2023) The Potential of Dental Calculus as a Novel Source of Biological Isotopic Data. in Exploring Human Behavior Through Isotope Analysis: Applications in Archaeological Research (eds. Beasley, M. M. & Somerville, A. D.) 125–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32268-6_6 13. Sørensen, L. K., Hasselstrøm, J. B., Larsen, L. S. and Bindslev, D. A. (2021) Entrapment of drugs in dental calculus - Detection validation based on test results from post-mortem investigations. Forensic Sci. Int. 319, 110647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110647 14. Bartholdy, Bjørn Peare, Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B., Sørensen, Lambert K., Casna, Maia, Hoogland, Menno, Historisch Genootschap Beemster and Henry, Amanda G. (2023) Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch population, Zenodo, 7649150, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7649150 | Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch population | Bartholdy, Bjørn Peare; Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B.; Sørensen, Lambert K.; Casna, Maia; Hoogland, Menno; Historisch Genootschap Beemster; Henry, Amanda G. | <p>Dental calculus is an excellent source of information on the dietary patterns of past populations, including consumption of plant-based items. The detection of plant-derived residues such as alkaloids and their metabolites in dental calculus pr... |  | Bioarchaeology, Post-medieval | Louise Le Meillour | Mario Zimmerman, Anonymous | 2023-07-31 17:21:40 | View |

30 Sep 2022

Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF dataBharath Nair, Ismael Rodríguez Palomo, Bo Markussen, Carsten Wiuf, Sarah Fiddyment and Matthew Collins https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.13.483627Assessing glutamine deamination in ancient parchment samplesRecommended by Beatrice Demarchi based on reviews by Maria Codlin and 3 anonymous reviewersData authenticity and approaches to data authentication are crucial issues in ancient protein research. The advent of modern mass spectrometry has enabled the detection of traces of ancient biomolecules contained in fossils, including protein sequences. However, detecting proteins in ancient samples does not equate to demonstrating their endogenous nature: instead, if the mechanisms that drive protein preservation and degradation are understood, then the extent of protein diagenesis can be used for evaluating preservational quality, which in turn may be related to the authenticity of the protein data. The post-mortem deamidation of asparaginyl and glutamyl residues is a key degradation reaction, which can be assessed effectively on the basis of mass spectrometry data, and which has accrued a long history of research, both in terms of describing the mechanisms governing the reactions and with regard to the best strategies for assessing and quantifying the extent of glutamine (Gln) and asparagine (Asn) deamidation in ancient samples (Pal Chowdhury et al., 2019; Ramsøe et al., 2021, 2020; Schroeter and Cleland, 2016; Simpson et al., 2016; Solazzo et al., 2014; Welker et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2012). In their paper, Nair and colleagues (2022) build on this wealth of knowledge and present a tool for quantifying the extent of Gln deamidation in parchment. Parchment is a collagen-based material which can yield extraordinary insights into manuscript manufacturing practices in the past, as well as on the daily lives of the people who assembled and used them (“biocodicology”) (Fiddyment et al., 2021, 2019, 2015; Teasdale et al., 2017). Importantly, the extent of deamidation can be directly related to the quality of the parchment produced: rapid direct deamidation of Gln is induced by the liming process, therefore high extents of deamidation are linked to prolonged exposure to the high pH conditions which are typical of liming, thus implying lower-quality parchment. Nair et al.’s approach focuses on collagen peptides which are typically detected during MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analyses of parchment and build a simple three-step workflow able to yield an overall index of deamidation for a sample (the parchment glutamine index - PQI) 一 taking into account that different Gln residues degrade at different rates according to their micro-chemical environment. The first step involves pre-processing the MALDI spectra, since Nair et al. are specifically interested in maximising information which can be obtained by low-quality data. The second step builds on well-established methods for quantifying Q → E from MALDI-TOF data by modelling the convoluted isotope distributions (Wilson et al., 2012). Once relative rates of deamidation in selected peptides within a given sample are calculated, the third step uses a mixed effects model to combine the individual deamidation estimates and to obtain an overall estimate of the deamidation for a parchment sample (PQI). The PQI can be used effectively for assessing parchment quality, as the authors show for the dataset from Orval Abbey. However, PQI could also have wider applications to the study of processed collagen, which is widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries. In general, the study by Nair et al. is a welcome addition to a growing body of research on protein diagenesis, which will ultimately improve models for the assessment of the authenticity of biomolecular data in archaeology. References Chowdhury, P.M., Wogelius, R., Manning, P.L., Metz, L., Slimak, L., and Buckley, M. 2019. Collagen deamidation in archaeological bone as an assessment for relative decay rates. Archaeometry 61:1382–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12492 Fiddyment, S., Goodison, N.J., Brenner, E., Signorello, S., Price, K., and Collins, M.J.. 2021. Girding the loins? Direct evidence of the use of a medieval parchment birthing girdle from biomolecular analysis. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.202055 Fiddyment,S., Holsinger, B., Ruzzier, C., Devine, A., Binois, A., Albarella, U., Fischer, R., Nichols, E., Curtis, A., Cheese, E., Teasdale, M.D., Checkley-Scott, C., Milner, S.J., Rudy, K.M., Johnson, E.J., Vnouček, J., Garrison, M., McGrory, S., Bradley, D.G., and Collins, M.J. 2015. Animal origin of 13th-century uterine vellum revealed using noninvasive peptide fingerprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:15066–15071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1512264112 Fiddyment, S., Teasdale, M.D., Vnouček, J., Lévêque, É., Binois, A., and Collins, M.J. 2019. So you want to do biocodicology? A field guide to the biological analysis of parchment. Heritage Science 7:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0278-6 Nair, B., Rodríguez Palomo, I., Markussen, B., Wiuf, C., Fiddyment, S., and Collins, M. Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF data. BiorRxiv, 2022.03.13.483627, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.13.483627 Ramsøe, A., Crispin, M., Mackie, M., McGrath, K., Fischer, R., Demarchi, B., Collins, M.J., Hendy, J., and Speller, C. 2021. Assessing the degradation of ancient milk proteins through site-specific deamidation patterns. Sci Rep 11:7795. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87125-x Ramsøe, A., van Heekeren, V., Ponce, P., Fischer, R., Barnes, I., Speller, C., and Collins, M.J. 2020. DeamiDATE 1.0: Site-specific deamidation as a tool to assess authenticity of members of ancient proteomes. J Archaeol Sci 115:105080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2020.105080 Schroeter, E.R., and Cleland, T.P. 2016. Glutamine deamidation: an indicator of antiquity, or preservational quality? Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 30:251–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7445 Simpson, J.P., Penkman, K.E.H., and Demarchi, B. 2016. The effects of demineralisation and sampling point variability on the measurement of glutamine deamidation in type I collagen extracted from bone. J Archaeol Sci 69: 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.002 Solazzo, C., Wilson, J., Dyer, J.M., Clerens, S., Plowman, J.E., von Holstein, I., Walton Rogers, P., Peacock, E.E., and Collins, M.J. 2014. Modeling deamidation in sheep α-keratin peptides and application to archeological wool textiles. Anal Chem 86:567–575. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac4026362 Teasdale, M.D., Fiddyment, S., Vnouček, J., Mattiangeli, V., Speller, C., Binois, A., Carver, M., Dand, C., Newfield, T.P., Webb, C.C., Bradley, D.G., and Collins M.J. 2017. The York Gospels: a 1000-year biological palimpsest. R Soc Open Sci 4:170988. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.170988 Welker, F., Soressi, M.A., Roussel, M., van Riemsdijk, I., Hublin, J.-J., and Collins, M.J. 2016. Variations in glutamine deamidation for a Châtelperronian bone assemblage as measured by peptide mass fingerprinting of collagen. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 3:15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2016.1258825 Wilson, J., van Doorn, N.L., and Collins, M.J. 2012. Assessing the extent of bone degradation using glutamine deamidation in collagen. Anal Chem 84:9041–9048. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac301333t | Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF data | Bharath Nair, Ismael Rodríguez Palomo, Bo Markussen, Carsten Wiuf, Sarah Fiddyment and Matthew Collins | <p style="text-align: justify;">Parchment was used as a writing material in the Middle Ages and was made using animal skins by liming them with Ca(OH)<span class="math-tex">\( _2 \)</span>. During liming, collagen peptides containing Glutamine (Q)... | Bioarchaeology, Europe, Medieval, Zooarchaeology | Beatrice Demarchi | 2022-03-22 12:54:10 | View | ||

23 Nov 2023

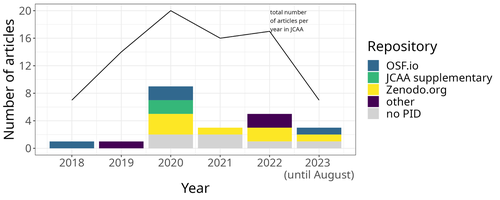

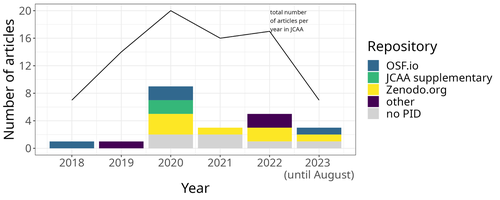

Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publicationSophie C Schmidt; Simon Maddison https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7966497Sharing Research Code in ArchaeologyRecommended by James Allison based on reviews by Thomas Rose, Joe Roe and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Thomas Rose, Joe Roe and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper “Percolation Package – From Script Sharing to Package Publication” by Sophie C. Schmidt and Simon Maddison (2023) describes the development of an R package designed to apply Percolation Analysis to archaeological spatial data. In an earlier publication, Maddison and Schmidt (2020) describe Percolation Analysis and provide case studies that demonstrate its usefulness at different spatial scales. In the current paper, the authors use their experience collaborating to develop the R package as part of a broader argument for the importance of code sharing to the research process. The paper begins by describing the development process of the R package, beginning with borrowing code from a geographer, refining it to fit archaeological case studies, and then collaborating to further refine and systematize the code into an R package that is more easily reusable by other researchers. As the review by Joe Roe noted, a strength of the paper is “presenting the development process as it actually happens rather than in an idealized form.” The authors also include a section about the lessons learned from their experience. Moving on from the anecdotal data of their own experience, the authors also explore code sharing practices in archaeology by briefly examining two datasets. One dataset comes from “open-archaeo” (https://open-archaeo.info/), an on-line list of open-source archaeological software maintained by Zack Batist. The other dataset includes articles published between 2018 and 2023 in the Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology. Schmidt and Maddison find that these two datasets provide contrasting views of code sharing in archaeology: many of the resources in the open-archaeo list are housed on Github, lack persistent object identifiers, and many are not easily findable (other than through the open-archaeo list). Research software attached to the published articles, on the other hand, is more easily findable either as a supplement to the published article, or in a repository with a DOI. The examination of code sharing in archaeology through these two datasets is preliminary and incomplete, but it does show that further research into archaeologists’ code-writing and code-sharing practices could be useful. Archaeologists often create software tools to facilitate their research, but how often? How often is research software shared with published articles? How much attention is given to documentation or making the software usable for other researchers? What are best (or good) practices for sharing code to make it findable and usable? Schmidt and Maddison’s paper provides partial answers to these questions, but a more thorough study of code sharing in archaeology would be useful. Differences among journals in how often they publish articles with shared code, or the effects of age, gender, nationality, or context of employment on attitudes toward code sharing seem like obvious factors for a future study to consider. Shared code that is easy to find and easy to use benefits the researchers who adopt code written by others, but code authors also have much to gain by sharing. Properly shared code becomes a citable research product, and the act of code sharing can lead to productive research collaborations, as Schmidt and Maddison describe from their own experience. The strength of this paper is the attention it brings to current code-sharing practices in archaeology. I hope the paper will also help improve code sharing in archaeology by inspiring more archaeologists to share their research code so other researchers can find and use (and cite) it. References Maddison, M.S. and Schmidt, S.C. (2020). Percolation Analysis – Archaeological Applications at Widely Different Spatial Scales. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 3(1), p.269–287. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcaa.54 Schmidt, S. C., and Maddison, M. S. (2023). Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publication, Zenodo, 7966497, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7966497 | Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publication | Sophie C Schmidt; Simon Maddison | <p>In this paper we trace the development of an R-package starting with the adaptation of code from a different field, via scripts shared between colleagues, to a published package that is being successfully used by researchers world-wide. Our aim... |  | Computational archaeology | James Allison | 2023-05-24 15:40:15 | View | |

19 Jun 2020

Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilitiesCédric Gaucherel and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/wn5zaThe means of complexity in a lithic reduction sequenceRecommended by Marta Arzarello based on reviews by Antony Borel and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Antony Borel and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper entitled “Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities” [1] submitted by C. Gaucherel and C. Noûs represents an interesting reflection about the possibilities to detect the human cognitive abilities in relation to the lithic production. The definition and the study of human cognitive abilities during the Lower Palaeolithic it has always been a complex field of investigation. The relation between the technical skills (lithic production) and the emergence of the linguistic abilities is not easy to investigate due to the difficulty of finding objective data to refer to. The proposition, made by C. Gaucherel and C. Noûs, of a formal grammar of knapping as a method to study the syntactical organisation of the reduction sequences, constitute a new and theoretical useful approach. In order to effectively and precisely define the gestures linked to a specific reduction sequence, for example that of the handaxes shaping, a very large number of variables should be taken into consideration (morphology and quality of the raw material, experience of the knapper, context, percussion technique, forecast of use of the handaxe, etc.). But since a simplification, that brings more elements than the classic one [2,3] is needed, the “action grammar approach” can be a good instrument to detect the common element in a shaping reduction sequence. Furthermore, one of the advantages of the proposed methodology lies in the fact that the definition of the different STs (Stone Technology) can be done according to the technological specific characteristics to be studied and to the type of instrument produced. The deconstruction of knapping sequences could help to detect the degree of complexity of the different steps of the reduction sequences also thanks to the identification of the sub-actions types. The increasing/decreasing of complexity is a very complicate concept in lithic technology. Since at the base of the lithic production there are two basic concepts (angle between the striking platform and the debitage surface - convexity of the debitage/façonnage surface) which are simply declined in an increasingly complex way, it is not easy to define uniquely in what exactly consists the increase in complexity. The approach proposed in the paper “Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities” can help to have new evidences, according to the identification of the required cognitive abilities. The proposed example of formal grammar still needs to be confirmed on archaeological collections, but it is probable that a practical application will allow to further develop the methodology and possibly to highlight additional possibilities of the approach. Bibliography [1] Gaucherel, C. and Noûs C. (2020). Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities. Paleorxiv, wn5za, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/wn5za | Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities | Cédric Gaucherel and Camille Noûs | <p>Recent studies in cognitive neurosciences have postulated a possible link between manual praxis such as tool-making and human languages. If confirmed, such a link opens significant avenues towards the study of the evolution of natural languages... |  | Africa, Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Theoretical archaeology | Marta Arzarello | 2020-04-30 14:18:26 | View | |

02 Nov 2020

Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case StudyJoseph Lewis https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/mxas2A probabilistic method for Least Cost Path calculation.Recommended by Otis Crandell based on reviews by Georges Abou Diwan and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper entitled “Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study” [1] submitted by J. Lewis presents an innovative approach to applying Least Cost Path (LCP) analysis to incorporate uncertainty of the Digital Elevation Model used as the topographic surface on which the path is calculated. The proposition of using Monte Carlo simulations to produce numerous LCP, each with a slightly different DEM included in the error range of the model, allows one to strengthen the method by proposing a probabilistic LCP rather than a single and arbitrary one which does not take into account the uncertainty of the topographic reconstruction. This new method is integrated in the R package leastcostpath [2]. The author tests the method using a Roman road built along a ridge in Cumbria, England. The integration of the uncertainty of the DEM, thanks to Monte Carlo simulations, shows that two paths could have the same probability to be the real LCP. One of them is indeed the path that the Roman road took. In particular, it is one of two possibilities of LCP in the south to north direction. This new probabilistic method therefore strengthens the reconstruction of past pathways, while also allowing new hypotheses to be tested, and, in this case study, to suggest that the northern part of the Roman road’s location was selected to help the northward movements. [1] Lewis, J., 2020. Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study. SocArXiv, mxas2, ver 17 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology, 10.31235/osf.io/mxas2. [2] Lewis, J., 2020. leastcostpath: Modelling Pathways and Movement Potential Within a Landscape. R package. Version 1.7.4. | Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study | Joseph Lewis | <p>The movement of past peoples in the landscape has been studied extensively through the use of Least Cost Path (LCP) analysis. Although methodological issues of applying LCP analysis in Archaeology have frequently been discussed, the effect of v... |  | Spatial analysis | Otis Crandell | Adam Green, Georges Abou Diwan | 2020-08-05 12:10:46 | View |

15 Aug 2021

Ran-thok and Ling-chhom: indigenous grinding stones of Shertukpen tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, IndiaNorbu Jamchu Thongdok, Gibji Nimasow & Oyi Dai Nimasow https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5118675An insight into traditional method of food production in IndiaRecommended by Otis Crandell based on reviews by Antony Borel, Atefeh Shekofteh, Andrea Squitieri, Birgül Ögüt, Atefe Shekofte and 1 anonymous reviewerThis paper [1] covers an interesting topic in that it presents through ethnography an insight into a traditional method of food production which is gradually declining in use. In addition to preserving traditional knowledge, the ethnographic study of grinding stones has the potential for showing how similar tools may have been used by people in the past, particularly from the same geographic region. [1] Thongdok Norbu J., Nimasow Gibji, Nimasow Oyi D. (2021) Ran-thok and Ling-chhom: indigenous grinding stones of Shertukpen tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, India. Zenodo, 5118675, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeo. doi: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5118675 | Ran-thok and Ling-chhom: indigenous grinding stones of Shertukpen tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, India | Norbu Jamchu Thongdok, Gibji Nimasow & Oyi Dai Nimasow | <p style="text-align: justify;">The Shertukpens are an Indigenous tribal group inhabiting the western and southern parts of Arunachal Pradesh, Northeast India. They are accomplished carvers of carving wood and stone. The paper aims to document the... | Antiquity, Asia, Environmental archaeology, Lithic technology, Peopling, Raw materials | Otis Crandell | 2021-02-10 10:26:12 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer