Latest recommendations

| Id▼ | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

02 Apr 2024

The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial CommunityAlphaeus Lien-Talks https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307882A nice project looking at under-represented demographicRecommended by Alexis Pantos based on reviews by Catriona Cooper and Steinar Kristensen based on reviews by Catriona Cooper and Steinar Kristensen

The paper by A. Lien-Talks [1] presents a small project looking at the use of crowd sourced data collection and particpatory GIS. In particular it looks at the potential of these tools in response to socially disruptive and isolating events such as the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the potential role of digitially mediated heritage initiatives in tackling some of the challenges of changing demographics and life styles. The types of technologies employed are relatively mature, the project identifies potential for such approaches to be used within the local-history/local community settings, though is also a reminer that depsite the much broader adoption of technology within all areas of society than even a few years ago many barriers still remain. While the the sample size and data collected in the project is relatively modest, the focus on empathy toward the intended audiences from the design process, as well as some of the qualitative feedback reported serve as a reminder that participatory, or crowd-sourced data collection initiatives in heritage can, and perhaps should place potential social benefit before data-acquisition of objectives. The project also presents a demographic that is not often represented within the literature and the publication and as such the publication of the article represents a meaningful contribution to ongoing discussions of the role heritage and digitally mediated community archaeology can play a role in developing our societies. References [1] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial Community. Zenodo, 8307882, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307882 | The Ashwell Project: Creating an Online Geospatial Community | Alphaeus Lien-Talks | <p>Background:<br>As the world becomes increasingly digital, so too must the way in which archaeologists engage with the public. This was particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic, and many outreach and engagement efforts began to move o... |  | Computational archaeology | Alexis Pantos | 2023-09-01 11:25:54 | View | |

Today

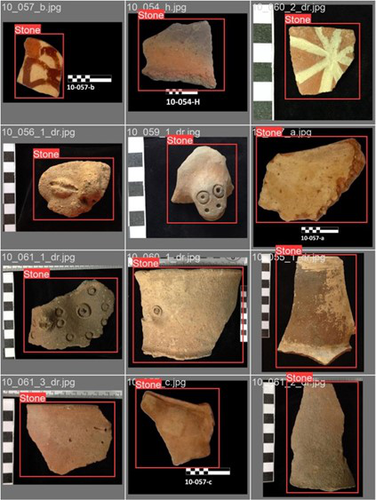

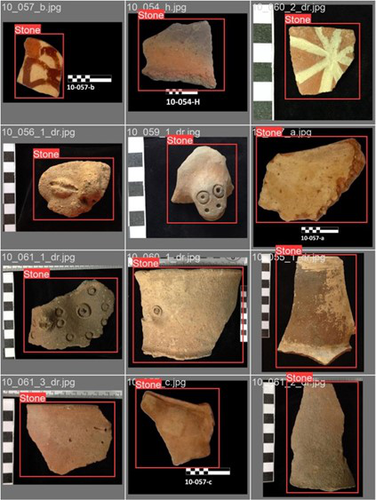

Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard PracticesSharp Kayeleigh, Christofis Brooklyn, Eslamiat Hossein, Nepal Upesh, Osores Mendives Carlos https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307612A step forward in detecting small objects in UAV data for archaeological surveyingRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In this paper [1], the authors describe how they apply machine learning with YOLOv5 to classify visual data, aiming to enhance understanding of archaeological phenomena before conducting destructive fieldwork. Despite challenges, the integration of machine learning with remote sensing technology was seen as transformative, enabling precise recording of areas of interest and assessment of environmental risk factors. The paper discusses successes, failures, and future directions in machine learning research, emphasising the need for standardisation and integration of streamlined methods. The application of machine learning techniques facilitates non-destructive analysis of material culture records, improving conservation efforts and offering insights into both past and contemporary phenomena. While the initial use of YOLOv5 showed potential for consistent detection of archaeological features, further refinement and dataset enlargement are deemed necessary for broader application in non-destructive archaeological surveying. The authors advocate for the integration of machine learning tools in archaeological research to save time, resources, and promote ethical digital recording practices. They highlight the importance of standardised methodologies to enhance credibility and reproducibility, aiming to contribute to the ongoing dialogue in computational archaeology. Overall, I think this paper is a good step forward in detecting small objects in UAV data, and contains useful information for similar studies. The aim towards greater reproducibility and standardisation is of course shared more widely in the machine learning community, and this study is a good example of how to approach this. References [1] Sharp, K., Christofis, B., Eslamiat, H., Nepal, U. and Osores Mendives, C. (2024). Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard Practices. Zenodo, 8307612, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307612 | Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard Practices | Sharp Kayeleigh, Christofis Brooklyn, Eslamiat Hossein, Nepal Upesh, Osores Mendives Carlos | <p>Our collaborative work began in 2019 with the intent to overcome obstacles that had arisen from the inability to access curated artifact collections from remote locations. It was our specific aim to not only create digital twins of excavated ob... |  | Ceramics, Computational archaeology, Remote sensing, South America | Alex Brandsen | 2023-09-01 09:56:18 | View | |

29 Apr 2024

Study and enhancement of the heritage value of a fortified settlement along the Limes Arabicus. Umm ar-Rasas (Amman, Jordan) between remote sensing analysis, photogrammetry and laser scanner surveys.Di Palma Francesca, Gabrielli Roberto, Merola Pasquale, Miccoli Ilaria, Scardozzi Giuseppe https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8306381Integrating remote sensing and photogrammetric approaches to studying a fortified settlement along the Limes Arabicus: Umm ar‐Rasas (Amman, Jordan).Recommended by Alessia Brucato based on reviews by Francesc C. Conesa, Giuseppe Ceraudo and 1 anonymous reviewerDi Palma et alii manuscript delves into applying remote sensing and photogrammetry methods to document and analyze the castrum at the Umm er-Rasas site in Jordan. This research aimed to map all the known archaeological evidence, detect new historical structures, and create a digital archive of the site's features for study and education purposes [1]. Their research has been organized into two phases. The first one consisted of a remote sensing survey and involved collecting historical and modern aerial and satellite imagery, such as: aerial photographs by Sir Marc Aurel Stein from 1939; panchromatic spy satellite images from the Cold War period (Corona KH-4B and Hexagon KH-9); high and very high resolution (HR and VHR) modern multispectral satellite images (Pléiades-1A and Pléiades Neo-4) [1]. This dataset was processed using the ENVI 4.4 software and applying multiple image-enhancing techniques (Pansharpening, RGB composite, data fusion, and Principal Component Analysis). Then, the resulting images were integrated into a QGIS project, allowing for visual analyses of the site's features and terrain. These investigations provided: · a broad overview of the site, · the discovery of a previously unknown archaeological feature (the northeastern dam), · a stage for targeted ground-level investigations [1]. The project's second phase was dedicated to intensive fieldwork operations, including pedestrian surveys, stratigraphic excavations, and photogrammetric recordings, such as: photographic reconstructions via Structure from Motion (SfM) and laser scanner sessions (using two FARO X330 HDR). In particular, the laser scanner data were processed with Reconstructor 4.4, which provided highly detailed 3D models for the QGIS database. These results were crucial in validating the information acquired during the first phase. Overall, the paper is well written, with clear objectives and a systematic presentation of the site [2,3,10,11], the research materials, and the study phases. The dataset was described in meticulous detail (especially the remote sensing sources and the laser scanner recordings). The methods implemented in this study are rigorously described [4,5,6,7,8,9] and show a high level of integration between aerial and field techniques. The results are neatly illustrated and fit into the current debates about the efficacy of remote sensing detection and multiscale approaches in archaeological research. In conclusion, this manuscript significantly contributes to archaeological research, unveiling new and exciting findings about the site of Umm er-Rasas. Its findings and methodologies warrant publication and further exploration. References: 1. Di Palma, F., Gabrielli, R., Merola, P., Miccoli, I. and Scardozzi, G. (2024). Study and enhancement of the heritage value of a fortified settlement along the Limes Arabicus. Umm ar-Rasas (Amman, Jordan) between remote sensing analysis, photogrammetry and laser scanner surveys. Zenodo, 8306381, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8306381 2. Abela J. and Acconci A. (1997), Umm al‐Rasas Kastron Mefa’a. Excavation Campaign 1997. Church of St. Paul: northern and southern flanks. Liber Annus, 47, 484‐488. 3. Bujard J. (2008), Kastron Mefaa, un bourg à l'époque byzantine: Travaux de la Mission archéologique de la Fondation Max van Berchem à Umm al‐Rasas, Jordanie (1988‐1997), PhD diss., University of Fribourg 2008. 4. Cozzolino M., Gabrielli R., Galatà P., Gentile V., Greco G., Scopinaro E. (2019), Combined use of 3D metric surveys and non‐invasive geophysical surveys at the stylite tower (Umm ar‐Rasas, Jordan), Annals of geophysics, 62, 3, 1‐9. http://dx.doi.org/10.4401/ag‐8060 5. Gabrielli R., Salvatori A., Lazzari A., Portarena D. (2016), Il sito di Umm ar‐Rasas – Kastron Mefaa – Giordania. Scavare documentare conservare, viaggio nella ricerca archeologica del CNR. Roma 2016, 236‐240. 6. Gabrielli R., Portarena D., Franceschinis M. (2017), Tecniche di documentazione dei tappeti musivi del sito archeologico di Umm al‐Rasas Kastron Mefaa (Giordania). Archeologia e calcolatori, 28 (1), 201‐218. https://doi.org/10.19282/AC.28.1.2017.12 7. Lasaponara R., Masini N. (2012 ed.), Satellite Remote Sensing: A New Tool for Archaeology, New York 2012. 8. Lasaponara R., Masini N. and Scardozzi G. (2007), Immagini satellitari ad alta risoluzione e ricerca archeologica: applicazioni e casi di studio con riprese pancromatiche e multispettrali di QuickBird. Archeologia e Calcolatori, 18 (2), 187‐227. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33150351.pdf 9. Lasaponara R., Masini N., Scardozzi G. (2010), Elaborazioni di immagini satellitari ad alta risoluzione e ricognizione archeologica per la conoscenza degli insediamenti rurali del territorio di Hierapolis di Frigia (Turchia). Il dialogo dei Saperi – Metodologie integrate per i Beni Culturali, Edizioni scientifiche italiane, 479‐494. 10. Piccirillo M., Abela J. and Pappalardo C. (2007), Umm al‐Rasas ‐ campagna 2007. Rapporto di scavo. Liber Annus, 57, 660‐668. 11. Poidebard A. (1934), La trace de Rome dans le désert de Syrie : le limes de Trajan à la conquête arabe ; recherches aériennes 1925 – 1932. Paris : Geuthner. | Study and enhancement of the heritage value of a fortified settlement along the Limes Arabicus. Umm ar-Rasas (Amman, Jordan) between remote sensing analysis, photogrammetry and laser scanner surveys. | Di Palma Francesca, Gabrielli Roberto, Merola Pasquale, Miccoli Ilaria, Scardozzi Giuseppe | <p>The Limes Arabicus is an excellent laboratory for experimenting with the huge potential of historical remote sensing data for identifying and mapping fortified centres along this sector of the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire and then the B... |  | Antiquity, Asia, Classic, Landscape archaeology, Mediterranean, Remote sensing, Spatial analysis | Alessia Brucato | 2023-08-31 23:34:16 | View | |

24 Jan 2024

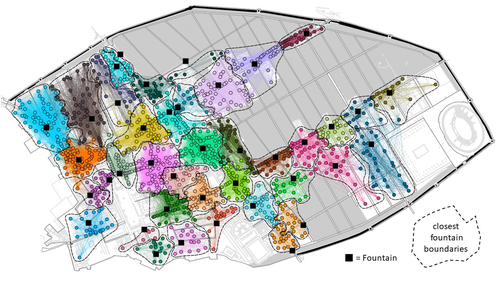

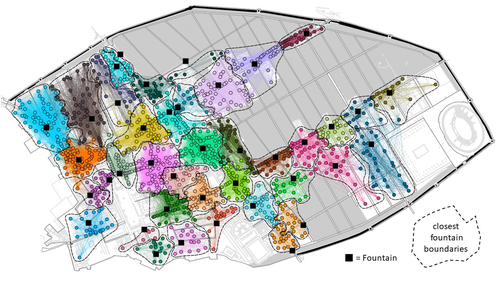

Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in PompeiiNotarian, Matthew https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305968A Valuable Contribution to Archaeological Network Research: A Case Study of PompeiiRecommended by David Laguna-Palma based on reviews by Matthew Peeples, Isaac Ullah and Philip Verhagen based on reviews by Matthew Peeples, Isaac Ullah and Philip Verhagen

The paper entitled 'Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii' [1] presents a significant contribution to the field of archaeological network research, particularly in the challenging task of identifying urban neighborhoods within the context of Pompeii. This study focuses on the relational dynamics within urban neighborhoods and examines their indistinct boundaries through advanced analytical methods. The methodology employed provides a comprehensive analysis of community detection, including the Louvain and Leiden algorithms, and introduces a novel Convex Hull of Admissible Modularity Partitions (CHAMP) algorithm. The incorporation of a network approach into this domain is both innovative and timely. The potential impact of this research is substantial, offering new perspectives and analytical tools. This opens new avenues for understanding social structures in ancient urban settings, which can be applied to other archaeological contexts beyond Pompeii. Moreover, the manuscript is not only methodologically solid but also well-written and structured, making complex concepts accessible to a broad audience. In conclusion, this study represents a valuable contribution to the field of archaeology, particularly for archaeological network research. Their results not only enhance our knowledge of Pompeii but also provide a robust framework for future studies in similar historical contexts. Therefore, this publication advances our understanding of social dynamics in historical urban environments. The rigorous analysis, combined with the innovative application of network algorithms, makes this study a noteworthy addition to the existing body of network science literature. It is recommended for a wide range of scholars interested in the intersection of archaeology, history, and network science. Reference [1] Notarian, Matthew. 2024. Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305968 | Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii | Notarian, Matthew | <p>The definition and identification of urban neighbourhoods in archaeological contexts remain complex and problematic, both theoretically and empirically. As constructs with both social and spatial characteristics, their detection through materia... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Computational archaeology, Mediterranean | David Laguna-Palma | 2023-08-31 19:28:35 | View | |

02 Jan 2024

Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenariosDiamanti, Eleni; Yip, Mauhing; Stahl, Annette; Ødegård, Øyvind https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305098Beyond Deep Blue: Underwater robotics, simulations and archaeologyRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Marco Moderato and 1 anonymous reviewerDiamanti et al. (2024) is a significant contribution to the field of underwater robotics and their use in archaeology, with an innovative approach to some major problems in the deployment of said technologies. It identifies issues when it comes to approaching Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) sites and does so through an interest in the combination of data, maneuverability, and the interpretation provided by the instruments that archaeologists operate. The article's motives are clear: it is not enough to find the means to reach these sites, but rather is fundamental to take a step forward in methodology and how we can safeguard certain aspects of data recovery with robust mission planning. To this end, the article does not fail to highlight previous contributions, in an intertwined web of references that demonstrate the marked evolution of the use of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), Remote Operated Vehicles (ROVs), Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Autonomous Surface Vehicles (ASVs), which are growing exponentially in use (see Kapetanović et al. 2020). It should be emphasized that the notion of ‘aquatic environment’ used here is quite broad and is not limited to oceanic or maritime environments, which allows for a larger perspective on distinct technologies that proliferate in underwater archaeology. There is also a relevant discussion on the typologies of sensors and how these autonomous vehicles obtain their data, where are debated Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) and LiDAR systems. Thus, the authors of this article propose the creation of a model that acquires data through simulations, which allows for a better understanding of what a real mission presupposes in the field. Their tripartite method - pre-mission planning; mission plan and post-mission plan - offers a performing algorithm that simplifies and provides reliability to all the parts of the intervention. The use of real cases to create simulation models allows for a substantial approximation to common practice in underwater environments. And yet, the article is at its most innovative status when it combines all the elements it sets out to explore. It could simply focus on the methodological or planning component, on obtaining data, or on theoretical problems. But it goes further, which makes this approach more complete and of interest to the archaeological community. By not taking any part as isolated, the problems and possible solutions arising from the course of the mission are carried over from one parameter to another, where details are worked upon and efficiency goals are set. One of the most significant cases is the tuning of ocean optics in aquatic environments according to the idiosyncracies of real cases (Diamanti et al. 2024: 8), a complex endeavor but absolutely necessary in order to increase the informative potential of the simulation. The exploration of various data capture models is also welcome, for the purposes of comparison and adaptation on a case-by-case basis. The brief theoretical reflection offered at the end of the article dwells in all these points and problematizes the difference between terrestrial and aquatic archaeology. In fact, the distinction does not only exist in the technical component, as although it draws in theoretical elements from archaeology that is carried out on land (see Krieger 2012 for this matter), the problems and interpretations are shaped by different factors and therefore become unique (Diamanti et al 2024: 15). The future, according to the authors, lies in increasing the autonomy of these vehicles so that the human element does not have to make decisions in a systematic way. It is in that note, and in order for that path to become closer to reality, that we strongly recommend this article for publication, in conjunction with the comments of the reviewers. We hope that its integrated approach, which brings together methods, theories and reflections, can become a broader modus operandi within the field of underwater robotics applied to archaeology. References: Diamanti, E., Yip, M., Stahl, A. and Ødegård, Ø. (2024). Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenarios, Zenodo, 8305098, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305098 Kapetanović, N., Vasilijević, A., Nađ, Đ., Zubčić, K., and Mišković, N. (2020). Marine Robots Mapping the Present and the Past: Unraveling the Secrets of the Deep. Remote Sensing, 12(23), 3902. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/rs12233902 Krieger, W. H. (2012). Theory, Locality, and Methodology in Archaeology: Just Add Water? HOPOS: The Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science, 2(2), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1086/666956

| Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenarios | Diamanti, Eleni; Yip, Mauhing; Stahl, Annette; Ødegård, Øyvind | <p>This paper presents a novel method for visual-based 3D mapping of underwater cultural heritage sites through marine robotic operations. The proposed methodology addresses the three main stages of an underwater robotic mission, specifically the ... | Computational archaeology, Remote sensing | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-08-31 16:03:10 | View | ||

03 Nov 2023

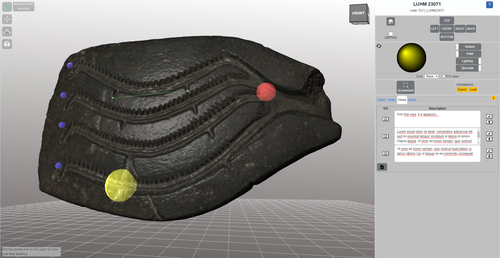

The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep InteractionMarco Callieri, Åsa Berggren, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Paola Derudas, Domenica Dininno, Fredrik Ekengren, Giuseppe Naponiello https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10067103A comparative teaching and learning tool for 3D data: Dynamic CollectionsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Louise Tharandt based on reviews by Alex Brandsen and Louise Tharandt

The paper (Callieri, M. et al. 2023) describes the “Dynamic Collections” project, an online platform initially created to showcase digital archaeological collections of Lund University. During a phase of testing by department members, new functionalities and artefacts were added resulting in an interactive platform adapted to university-level teaching and learning. The paper introduces into the topic and related works after which it starts to explain the project itself. The idea is to resemble the possibilities of interaction of non-digital collections in an online platform. Besides the objects themselves, the online platform offers annotations, measurement and other interactive tools based on the already known 3DHOP framework. With the possibility to create custom online collections a collaborative working/teaching environment can be created. The already wide-spread use of the 3DHOP framework enabled the authors to develop some functionalities that could be used in the “Dynamic Collections” project. Also, current and future plans of the project are discussed and will include multiple 3D models for one object or permanent identifiers, which are both important additions to the system. The paper then continues to explain some of its further planned improvements, like comparisons and support for teaching, which will make the tool an important asset for future university-level education. The paper in general is well-written and informative and introduces into the interactive tool, that is already available and working. It is very positive, that the authors rely on up-to-date methodologies in creating 3D online repositories and are in fact improving them by testing the tool in a teaching environment. They mention several times the alignment with upcoming EU efforts related to the European Collaborative Cloud for Cultural Heritage (ECCCH), which is anticipatory and far-sighted and adds to the longevity of the project. Comments of the reviewers were reasonably implemented and led to a clearer and more concise paper. I am very confident that this tool will find good use in heritage research and presentation as well as in university-level teaching and learning. Although the authors never answer the introductory question explicitly (What characteristics should a virtual environment have in order to trigger dynamic interaction?), the paper gives the implicit answer by showing what the "Dynamic Collections" project has achieved and is able to achieve in the future. BibliographyCallieri, M., Berggren, Å., Dell'Unto, N., Derudas, P., Dininno, D., Ekengren, F., and Naponiello, G. (2023). The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep Interaction, Zenodo, 10067103, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10067103 | The Dynamic Collections – a 3D Web Platform of Archaeological Artefacts designed for Data Reuse and Deep Interaction | Marco Callieri, Åsa Berggren, Nicolò Dell’Unto, Paola Derudas, Domenica Dininno, Fredrik Ekengren, Giuseppe Naponiello | <p>The Dynamic Collections project is an ongoing initiative pursued by the Visual Computing Lab ISTI-CNR in Italy and the Lund University Digital Archaeology Laboratory-DARKLab, Sweden. The aim of this project is to explore the possibilities offer... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-31 15:05:32 | View | |

11 Oct 2023

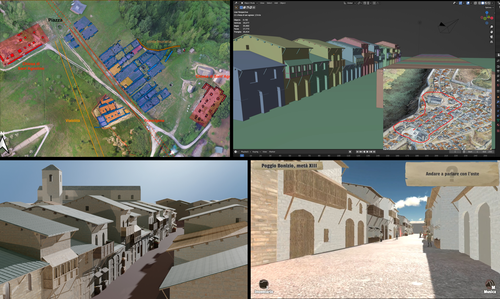

Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill ProjectSamanta Mariotti https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563Gamification of an archaeological park: The Living Hill Project as work-in-progressRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Andrew Reinhard, Erik Champion and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (2023) describes The Living Hill project dedicated to the archaeological park and fortress of Poggio Imperiale in Poggibonsi, Italy. The project is a collaboration between the Poggibonsi excavation and Entertainment Games App, Ltd. From the start, the project focused on the question of the intended audience rather than on the used technology. It was therefore planned to involve the audience in the creation of the game itself, which was not possible after all due to the covid pandemic. Nevertheless, the game aimed towards a visit experience as close as possible to reality to offer an educational tool through the video game, as it offers more periods than the medieval period showcased in the archaeological park itself. The game mechanics differ from a walking simulator, or a virtual tour and the player is tasked with returning three lost objects in the virtual game. While the medieval level was based on a 3D scan of the archaeological park, the other two levels were reconstructed based on archaeological material. Currently, only a PC version is working, but the team works on a mobile version as well and teased the possibility that the source code will be made available open source. Lastly, the team also evaluated the game and its perception through surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Although the surveys were only based on 21 persons, the results came back positive overall. The paper is well-written and follows a consistent structure. The authors clearly define the goals and setting of the project and how they developed and evaluated the game. Although it has be criticized that the game is not playable yet and the size of the questionnaire is too low, the authors clearly replied to the reviews and clarified the situation on both matters. They also attended to nearly all of the reviewers demands and answered them concisely in their response. In my personal opinion, I can fully recommend this paper for publication. For future works, it is recommended that the authors enlarge their audience for the quesstionaire in order to get more representative results. It it also recommended to make the game available as soon as possible also outside of the archaeological park. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their concise and constructive criticism to this paper as well as for their time. References Mariotti, Samanta. (2023) Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of The Living Hill Project, Zenodo, 8302563, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8302563 | Transforming the Archaeological Record Into a Digital Playground: a Methodological Analysis of *The Living Hill* Project | Samanta Mariotti | <p>Video games are now recognised as a valuable tool for disseminating and enhancing archaeological heritage. In Italy, the recent institutionalisation of Public Archaeology programs and incentives for digital innovation has resulted in a prolifer... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Europe, Medieval, Post-medieval | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-08-30 20:25:32 | View | |

16 Apr 2024

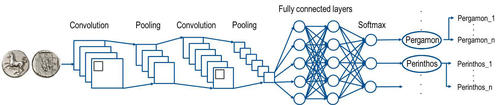

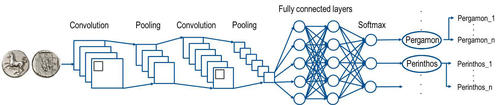

Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin DatasetSebastian Gampe, Karsten Tolle https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298077A significant contribution to the problem of unbalanced data in machine learning research in archaeologyRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by Simon Carrignon, Joel Santos and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Carrignon, Joel Santos and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper [1] presents an innovative approach to address the prevalent challenge of unbalanced datasets in coin type recognition, shifting the focus from coin class type recognition to coin mint recognition. Despite this shift, the issue of unbalanced data persists. To mitigate this, the authors introduce a method to split larger classes into smaller ones, integrating them into an 'additional class layer'. Three distinct machine learning (ML) methodologies were employed to identify new possible classes, with one approach utilising unsupervised clustering alongside manual intervention, while the others leverage object detection, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. However, despite these efforts, overfitting remained a persistent issue, prompting the authors to explore alternative methods such as dataset improvement and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). The paper contributes significantly to the intersection of ML techniques and archaeology, particularly in addressing overfitting challenges. Furthermore, the authors' candid acknowledgment of the limitations of their approaches serves as a valuable resource for researchers encountering similar obstacles. This study stems from the D4N4 project, aimed at developing a machine learning-based coin recognition model for the extensive "Corpus Nummorum" dataset, comprising over 19,600 coin types and 49,000 coins from various ancient landscapes. Despite encountering challenges with overfitting due to the dataset's imbalance, the authors' exploration of multiple methodologies and transparent documentation of their limitations enriches the academic discourse and provides a foundation for future research in this field. Reference [1] Gampe, S. and Tolle, K. (2024). Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin Dataset. Zenodo, 8298077, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298077 | Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin Dataset | Sebastian Gampe, Karsten Tolle | <p>We have implemented an approach based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for mint recognition for our Corpus Nummorum (CN) coin dataset as an alternative to coin type recognition, since we had too few instances for most of the types (classe... |  | Computational archaeology | Alex Brandsen | 2023-08-29 16:26:41 | View | |

28 Feb 2024

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and DutchAlex Brandsen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10610882Multilingual Named Entity Recognition in archaeology: an approach based on deep learningRecommended by Maria Pia di Buono based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch” (Brandsen 2024) explores the use of BERT-based models for Named Entity Recognition (NER) in archaeology across three languages: English, German, and Dutch. It introduces six models trained and fine-tuned on archaeological literature, followed by the presentation and evaluation of three models specifically tailored for NER tasks. The focus on multilingualism enhances the applicability of the research, while the meticulous evaluation using standard metrics demonstrates a rigorous methodology. The introduction of NER for extracting concepts from literature is intriguing, while the provision of a method for others to contribute to BERT model pre-training enhances collaborative research efforts. The innovative use of BERT models to contextualize archaeological data is a notable strength, bridging the gap between digitized information and computational models. Additionally, the paper's release of fine-tuned models and consideration of environmental implications add further value. In summary, the paper contributes significantly to the task of NER in archaeology, filling a crucial gap and providing foundational tools for data mining and reevaluating legacy archaeological materials and archives. Reference Brandsen, A. (2024). Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch. Zenodo, 8296920, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296920 | Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch | Alex Brandsen | <p>This short paper describes a collection of BERT models for the archaeology domain. We took existing language specific BERT models in English, German, and Dutch, and further pre-trained them with archaeology specific training data. We then took ... |  | Computational archaeology | Maria Pia di Buono | 2023-08-29 14:50:21 | View | |

08 Feb 2024

CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient CoinsUlrike Peter, Claus Franke, Jan Köster, Karsten Tolle, Sebastian Gampe, Vladimir F. Stolba https://zenodo.org/records/8263517The valuable Corpus Nummorum: a not so Little MinionRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Fleur Kemmers and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Fleur Kemmers and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper under review/recommendation deals with Corpus Nummorum (Peter et al. 2024). The Corpus Nummorum (CN) is web portal for ancient Greek coins from various collections (https://www.corpus-nummorum.eu/). The CN is a database and research tool for Greek coins dating between 600 BCE to 300 CE. While many traditional collection databases aim at collecting coins, CN also includes coin dies, coin types and issues. It aims at achieving a complete online coin type catalogue. The paper is not a paper in a traditional sense, but presents the CN as a tool and shows the functionalities in the system. The relevance and the possibilities of the CN for numismatists is made clear in the paper and the merits are clear even for me as a Roman archaeologist and non-numismatist. The CN was presented as a poster at the CAA 2023 in Amsterdam during “S03. Our Little Minions pt. V: small tools with major impact”, organized by Moritz Mennenga, Florian Thiery, Brigit Danthine and myself (Mennenga et al. 2023). Little Minions help us significantly in our daily work as small self-made scripts, home-grown small applications and small hardware devices. They often reduce our workload or optimize our workflows, but are generally under-represented during conferences and not often presented to the outside world. Therefore, the Little Minions form a platform that enables researchers and software engineers to share these tools (Thiery, Visser and Mennenga 2021). Little Minions have become a well known happening within the CAA-community since we started this in 2018, also because we do not only allow 10-minute lightning talks, but also spontaneous stand-up presentations during the conference. A full list of all minions presented in the past, can be found online: https://caa-minions.github.io/minions/. In a strict sense the CN would not count as a Little Minion, because it is a large project consisting of many minions that help a numismatist in his/her daily work. The CN seems a very Big Minion in that sense. Personally, I am very happy to see the database being developed as a fully open system and that code can be found on Github (https://github.com/telota/corpus-nummorum-editor), and also made citable with citation information in GitHub (see https://citation-file-format.github.io/) and a version deposited in Zenodo with DOI (Köster and Franke 2024). In addition, the authors claim that the CN will be shared based on the FAIR-principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016, 2019). These guidelines are developed to improve the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse of digital data. I feel that CN will be a way forward in open numismatics and open archaeology. The CN is well known within the numismatist community and it was hard to find reviewers in this close community, because many potential reviewers work together with one or more of the authors, or are involved in the project. This also proves the relevance of the CN to the research community and beyond. Luckily, a Roman numismatist and a specialist in digital/computational archaeology were able to provide valuable feedback on the current paper. The reviewers only submitted feedback on the first version of the paper (Peter et al. 2023). The numismatist was positive on the content and the usefulness of CN for the discipline in general. However, she pointed out some important points that need to be addressed. The digital specialist was positive is various aspects, but also raised some important issues in relation to technical aspects and the explanation thereof. While both were positive on the project and the paper in general, both reviewers pointed out some issues that were largely addressed in the second version of this paper. The revised version was edited throughout and the paper was strongly improved. The Corpus Nummorum is well presented in this easy to read paper, although the explanations can sometimes be slightly technical. This paper gives a good introduction to the CN and I recommend this for publication. I sincerely hope that the CN will contribute and keep on contributing to the domains of numismatics, (digital) archaeology and open science in general. References Köster, J and Franke, C. 2024 Corpus Nummorum Editor. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10458195 Mennenga, M, Visser, RM, Thiery, F and Danthine, B. 2023 S03. Our Little Minions pt. V: small tools with major impact. In:. Book of Abstracts. CAA 2023: 50 Years of Synergy. Amsterdam: Zenodo. pp. 249–251. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7930991 Peter, U, Franke, C, Köster, J, Tolle, K, Gampe, S and Stolba, VF. 2023 CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.8263518 Peter, U., Franke, C., Köster, J., Tolle, K., Gampe, S. and Stolba, V. F. (2024). CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins, Zenodo, 8263517, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8263517 Thiery, F, Visser, RM and Mennenga, M. 2021 Little Minions in Archaeology An open space for RSE software and small scripts in digital archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.4575167 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Aalbersberg, IjJ, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, ’t Hoen, PAC, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Velterop, J, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2016 The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1): 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Jan Aalbersberg, I, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, Hoen, PAC ’t, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Jan Velterop, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2019 Addendum: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 6(1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0009-6 | CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins | Ulrike Peter, Claus Franke, Jan Köster, Karsten Tolle, Sebastian Gampe, Vladimir F. Stolba | <p>CORPUS NUMMORUM indexes ancient Greek coins from various landscapes and develops typologies. The coins and coin types are published on the multilingual website www.corpus-nummorum.eu utilizing numismatic authority data and adhering to FAIR prin... |  | Antiquity, Classic | Ronald Visser | 2023-08-18 17:37:51 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer