Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

25 Jul 2023

Sorghum and finger millet cultivation during the Aksumite period: insights from ethnoarchaeological modelling and microbotanical analysisAbel Ruiz-Giralt, Alemseged Beldados, Stefano Biagetti, Francesca D’Agostini, A. Catherine D’Andrea, Yemane Meresa, Carla Lancelotti https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7859673An innovative integration of ethnoarchaeological models with phytolith data to study histories of C4 crop cultivationRecommended by Emma Loftus based on reviews by Tanya Hattingh and 1 anonymous reviewerThis article “Sorghum and finger millet cultivation during the Aksumite period: insights from ethnoarchaeological modelling and microbotanical analysis”, submitted by Ruiz-Giralt and colleagues (2023a), presents an innovative attempt to address the lack of palaeobotanical data concerning ancient agricultural strategies in the northern Horn of Africa. In lieu of well-preserved macrobotanical remains, an especial problem for C4 crop species, these authors leverage microbotanical remains (phytoliths), in combination with ethnoarchaeologically-informed agroecology models to investigate finger millet and sorghum cultivation during the period of the Aksumite Kingdom (c. 50 BCE – 800 CE). Both finger millet and sorghum have played important roles in the subsistence of the Horn region, and throughout much of the rest of Africa and the world in the past. The importance of these drought-resistant and adaptable crops is likely to increase as we move into a warmer, drier world. Yet their histories of cultivation are still only approximately sketched due to a paucity of well-preserved remains from archaeological sites - for example, debate continues as to the precise centre of their domestication. Recent studies of phytoliths (by these and other authors) are demonstrating the likely continuous presence of these crops from the pre-Aksumite period. However, phytoliths are diagnostic only to broad taxonomic levels, and cannot be used to securely identify species. To supplement these observations, Ruiz-Giralt et al. deploy models (previously developed by this team: Ruiz-Giralt et al., 2023b) that incorporate environmental variables and ethnographic data on traditional agrosystems. They evaluate the feasibility of different agricultural regimes around the locations of numerous archaeological sites distributed across the highlands of northern Ethiopia and southern Eritrea. Their results indicate the general viability of finger millet and sorghum cultivation around archaeological settlements in the past, with various regions displaying greater-or-lesser suitability at different distances from the site itself. The models also highlight the likelihood of farmers utilising extensive-rainfed regimes, given low water and soil nutrient requirements for these crops. The authors discuss the results with respect to data on phytolith assemblages, particularly at the site of Ona Adi. They conclude that Aksumite agriculture very likely included the cultivation of finger millet and sorghum, as part of a broader system of rainfed cereal cultivation. Ruiz-Giralt et al. argue, and have demonstrated, that ethnoarchaeologically-informed models can be used to generate hypotheses to be evaluated against archaeological data. The integration of many diverse lines of information in this paper certainly enriches the discussion of agricultural possibilities in the past, and the use of a modelling framework helps to formalise the available hypotheses. However, they emphasise that modelling approaches cannot be pursued in lieu of rigorous archaeobotanical studies but only in tandem - a greater commitment to archaeobotanical sampling is required in the region if we are to fully detail the histories of these important crops. References Ruiz-Giralt, A., Beldados, A., Biagetti, S., D’Agostini, F., D’Andrea, A. C., Meresa, Y. and Lancelotti, C. (2023a). Sorghum and finger millet cultivation during the Aksumite period: insights from ethnoarchaeological modelling and microbotanical analysis. Zenodo, 7859673, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7859673 Ruiz-Giralt, A., Biagetti, S., Madella, M. and Lancelotti, C. (2023b). Small-scale farming in drylands: New models for resilient practices of millet and sorghum cultivation. PLoS ONE 18, e0268120. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268120

| Sorghum and finger millet cultivation during the Aksumite period: insights from ethnoarchaeological modelling and microbotanical analysis | Abel Ruiz-Giralt, Alemseged Beldados, Stefano Biagetti, Francesca D’Agostini, A. Catherine D’Andrea, Yemane Meresa, Carla Lancelotti | <p>For centuries, finger millet (<em>Eleusine coracana</em> Gaertn.) and sorghum (<em>Sorghum bicolor</em> (L.) Moench) have been two of the most economically important staple crops in the northern Horn of Africa. Nonetheless, their agricultural h... | Africa, Archaeobotany, Computational archaeology, Protohistory, Spatial analysis | Emma Loftus | 2023-04-29 16:24:54 | View | ||

26 Apr 2022

Archaeophenomics of ancient domestic plants and animals using geometric morphometrics : a reviewAllowen Evin, Laurent Bouby, Vincent Bonhomme, Angèle Jeanty, Marine Jeanjean, Jean-Frédéric Terral https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/skeu5Archaeophenomics: an up-and-coming field in bioarchaeologyRecommended by Anneke H. van Heteren based on reviews by Stefan Schlager and 1 anonymous reviewerAnneke H. van Heteren based on reviews by Stefan Schlager and 1 anonymous reviewer Phenomics is the analysis of high-dimensional phenotypic data [1]. Phenomics research strategies are capable of linking genetic variation to phenotypic variation [2], but a genetic component is not absolutely necessary. The paper “Archaeophenomics of ancient domestic plants and animals using geometric morphometrics: a review” by Evin and colleagues [3] examines the use of geometric morphometrics in bioarchaeology and coins the term archaeophenomics. Archaeophenomics can be described as the large-scale phenotyping of ancient remains, and both addresses taxonomic identification, as well as infers spatio-temporal agrobiodiversity dynamics. It is a relatively new field in bioarchaeology with the first paper using this approach stemming from 2004. This study by Evin et al. [3] presents an excellent review and unquestionably demonstrates the potential of archaeophenomics. The authors provide an exhaustive review specifically of bioarchaeological studies in international journals using geometric morphometrics to study archaeological remains of domestic species. Although geometric morphometrics lends itself well for archaeophenomics, readers should keep in mind that this is not the only method and other approaches might equally fall under archaeophenomics as long as high-dimensional phenotypic archaeological data are involved. Distinguishing archaeophenomics from phenomics is important because of a critical difference. Archaeological remains are often altered by taphonomical processes. As such data may not be as complete as when working with modern specimens. Although this poses difficulties, morphometric analyses can usually still be performed as long as the structures presenting the relevant geometrical features are present. Even fragmented remains can be studied with a restricted version of the original landmarking/measurement protocol. Evin et al. [3] define archaeophenomics as “phenomics of the past”. This is only partly correct. It can be deduced from their review that they really mean phenomics of our (human) past. This leaves a gap for phenomics of the non-human past, for which I suggest the term palaeophenomics. [1] Jin, L. (2021). Welcome to the Phenomics Journal. Phenomics, 1, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43657-020-00009-4.

| Archaeophenomics of ancient domestic plants and animals using geometric morphometrics : a review | Allowen Evin, Laurent Bouby, Vincent Bonhomme, Angèle Jeanty, Marine Jeanjean, Jean-Frédéric Terral | <p>Geometric morphometrics revolutionized domestication studies through the precise quantification of the phenotype of ancient plant and animal remains. Geometric morphometrics allow for an increasingly detailed understanding of the past agrobiodi... |  | Archaeobotany, Archaeometry, Bioarchaeology, Zooarchaeology | Anneke H. van Heteren | 2022-02-17 09:50:39 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific RegionChristopher Buckley https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2From Polished Stone Tools to Population Dynamics: Ethnographic Archives as InsightsRecommended by Solène Denis based on reviews by Adrian L. Burke and 1 anonymous reviewerMost archaeological contexts provide objects without organic materials making them quite silent regarding their hafting techniques and use. This is especially true for the polished stone tools that only thanks to a few discoveries in a wet environment, we can obtain some insights regarding their hafting techniques. Use-wear analysis can also be of some support to get a better picture of these artefacts (e.g. Masclans Latorre 2020), whose typology testifies to an important diversity in European Neolithic contexts that sometimes are well-documented from the chaîne opératoire perspective (see De Labriffe and Thirault dir. 2012). The study offered by Chris Buckley (2023) constitutes an important contribution to animating these tools. His work relies on the Asia Pacific region, where he gathered data and mapped more than 300 ethnographic hafted stone and shell tools. This database is available on a webpage https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1D_sC7VUtQRuRcCgc9rROVU7ghrdiVAg&ll=-2.458804534247277%2C154.35254980859378&z=6, providing a short description and pictures of some of the items, completed by Supplementary data. Thanks to this important record of entire objects, the author presents the different possibilities regarding hafting styles, blade orientations and attachment techniques. The combination of these different characteristics led the author to the introduction of a dynamic typology based on the concept of ‘morphospace’. Eight types have been so identified for the Asia Pacific region. The geographical distribution of these types is then presented and questioned, bringing also to the forefront some archaeological findings. An emphasis is made on New Guinea island where documentation is important. We can mention the emblematic work of Anne-Marie and Pierre Pétrequin (1993 and 2020) focused on West Papua, providing one of the most consulted books on stone axes by archaeologists. The worthy explanations tested to understand this repartition mobilize archaeological or linguistic data to hypothesise a three waves model of innovations in link with agricultural practices. A discussion on the correlation between material culture and language highlights in the background the need for interdisciplinary to deal finely with these interactions and linkages as has been effectively demonstrated elsewhere (Hermann and Walworth 2020). To conclude, the convergence between European Neolithic and New Guinea polished stone tools is demonstrated here through ‘morphospace’ comparisons. Thanks to this study, the polished stone tools come alive more than any European archaeological context would allow. The population dynamics investigated through these tools are directly relevant to current scientific issues concerning material culture. This example of convergent evolution is therefore an important key to considering this article as a source of inspiration for the archaeological community. References Buckley C. (2023). Hafted Stone and Shell Tools in the Asia Pacific Region, PsyArXiv, v.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8cwa2 De Labriffe A., Thirault E. dir. (2012). Produire des haches au Néolithique, de la matière première à l’abandon, Paris, Société préhistorique française (Séances de la Société préhistorique française, 1). Hermann A., Walworth M. (2020). Approche interdisciplinaire des échanges interculturels et de l’intégration des communautés polynésiennes dans le centre du Vanuatu, Journal de la Société des Océanistes, 151, 239-262. https://doi-org.docelec.u-bordeaux.fr/10.4000/jso.11963 Masclans Latorre A. (2020). Use-wear Analyses of Polished and Bevelled Stone Artefacts during the Sepulcres de Fossa/Pit Burials Horizon (NE Iberia, c. 4000–3400 cal B.C.), Oxford, BAR Publishing (BAR International Series 2972). Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (1993). Écologie d'un outil : la hache de pierre en Irian Jaya (Indonésie), Paris, CNRS Editions. Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M. (2020). Ecology of a Tool: The ground stone axes of Irian Jaya (Indonesia). Oxbow Books. | Hafted stone and shell tools in the Asia Pacific Region | Christopher Buckley | <p>Hafted stone tools fell into disuse in the Pacific region in the 19th and 20th centuries. Before this occurred, examples of tools were collected by early travelers, explorers and tourists. These objects, which now reside in ethnographic collect... |  | Asia, Conservation/Museum studies, Lithic technology, Neolithic, Oceania | Solène Denis | 2022-11-09 18:37:08 | View | |

17 Dec 2020

Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbolsGuillaume Porraz, John E. Parkington, Patrick Schmidt, Gérald Bereiziat, Jean-Philip Brugal, Laure Dayet, Marina Igreja, Christopher E. Miller, Viola C. Schmid, Chantal Tribolo, Aurore Val, Christine Verna, Pierre-Jean Texier https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/ch53rExperimentation as a driving force for innovation in the Pre-Still Bay from Southern AfricaRecommended by Anne Delagnes based on reviews by Francesco d'Errico, Enza Elena Spinapolice and Kathryn RanhornThe article submitted by Guillaume Porraz et al. [1] shed light on the evolutionary changes recorded during the Pre-Still Bay Lynn stratigraphic unit (SU) from Diepkloof (Southern Africa). It promotes a multi-proxy and integrative approach based on a set of innovative behaviors, such as the engraving of geometric forms, silcrete heat- treatment, the use of adhesive, bladelet and bifacial tools production. This approach is not so common in Middle Stone Age (MSA) studies and makes a lot of sense for discussing the mechanisms that have fostered later innovations during the Still Bay and Howiesons Poort periods. The various innovations that emerge synchronously in this layer contrast with earlier innovations which appear as isolated phenomena in the MSA archaeological record. The strong inventiveness documented in Lynn SU is reported to a phase of experimentation for testing new ideas, new behaviors that would have played a crucial role for the emergence of the Still Bay in a context of socio-economic transformation. The data presented in this article broadens the scope of two previous articles [2-3] based on a more representative record, collected on an area of 3,5 m² opposed to 2 m² previously, and on the first presentation and description of an engraved bone with a rhomboid pattern. Macro- and microscopic analyses together with the analysis of the distribution of the engraved lines argue convincingly for an intentional engraving. This article constitutes a key contribution to the question of HOW emerged modern cultures in Southern Africa, while calling for further research related to sites’ function, environment and local resources to address the ever-debated question of WHY the MSA groups from Southern Africa developed such unprecedented inventiveness. It makes no doubt that this article deserves recommendation by PCI Archaeology. [1] Porraz, G., Schmidt, P., Bereiziat, G., Brugal, J.Ph., Dayet, L., Igreja, M., Miller, C.E., Viola, C., Tribolo, C., Val, A., Verna, C., Texier, P.J. 2020. Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbols. 10.32942/osf.io/ch53r [2] Porraz, G., Texier, P.J., Archer, W., Piboule, M., Rigaud, J.P, Tribolo, C. 2013. Technological successions in the Middle Stone Age sequence of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science 40, 3376–3400. 10.1016/j.jas.2013.02.012 [3] Porraz, G., Texier, J.P. Miller, C.E., 2014. Le complexe bifacial Still Bay et ses modalités d’émergence à l’abri Diepkloof (Middle Stone Age, Afrique du Sud). In: XXVIIème Congrès Préhistorique de France, Transitions, Ruptures et Continuité en Préhistoire. Mémoires de la Société Préhistorique Française, 155–175. | Experimentation preceding innovation in a MIS5 Pre-Still Bay layer from Diepkloof Rock Shelter (South Africa): emerging technologies and symbols | Guillaume Porraz, John E. Parkington, Patrick Schmidt, Gérald Bereiziat, Jean-Philip Brugal, Laure Dayet, Marina Igreja, Christopher E. Miller, Viola C. Schmid, Chantal Tribolo, Aurore Val, Christine Verna, Pierre-Jean Texier | <p>In South Africa, key technologies and symbolic behaviors develop as early as the later Middle Stone Age in MIS5. These innovations arise independently in various places, contexts and forms, until their full expression during the Still Bay and t... |  | Africa, Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic, Symbolic behaviours | Anne Delagnes | 2020-08-04 09:13:27 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Automation and Novelty –Archaeocomputational Typo-Praxis in the Wake of the Third Science RevolutionRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Rachel Crellin and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Rachel Crellin and 1 anonymous reviewer

“Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology” submitted by G. Lucas (1) offers a refreshing and welcome reflection on the role of computer-based practice, type-thinking and approaches to typology in the age of big data and the widely proclaimed ‘Third Science Revolution’ (2–4). At the annual meeting of the EAA in Maastricht in 2017, a special thematic block was dedicated to issues and opportunities linked to the Third Science Revolution in archaeology “because of [its] profound and wide ranging impact on practice and theory in archaeology for the years to come” (5). Even though the Third Science Revolution, as influentially outlined by Kristiansen in 2014 (2), has occasionally also been met with skepticism and critique as to its often implicit scientism and epistemological naivety (6–8), archaeology as a whole seems largely euphoric as to the promises of the advancing ‘revolution’. As Lucas perceptively points out, some even regard it as the long-awaited opportunity to finally fulfil the ambitions and goals of Anglophone processualism. The irony here, as Lucas rightly notes, is that early processualists initially foregrounded issues of theory and scientific epistemology, while much work conducted under the banner of the Third Science Revolution, especially within its computational branches, does not. Big data advocates have echoed Anderson’s much-cited “end of theory” (9) or at least emphatically called for an ‘empirization’ and ‘computationalization’ of theory, often under the banner of ‘data-driven archaeology’ (10), yet typically without much specification of what this is supposed to mean for archaeological theory and reflexivity. The latter is indeed often openly opposed by archaeological Third Science Revolution enthusiasts, arguably because it is viewed as part of the supposedly misguided ‘post-modernist’ project. Lucas makes an original meta-archaeological contribution here and attempts to center the epistemological, ontological and praxeological dimensions of what is actually – in situated archaeological praxis and knowledge-production – put at stake by the mobilization of computers, algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI), including its many but presently under-reflected implications for ordering practices such as typologization. Importantly, his perspective thereby explicitly and deliberately breaks with the ‘normative project’ in traditional philosophy of science, which sought to nail down a universal, prescriptive way of doing science and securing scientific knowledge. He instead focuses on the practical dimensions and consequences of computer-reliant archaeologies, what actually happens on the ground as researchers try to grapple with the digital and the artefactual and try to negotiate new insights and knowledge, including all of the involved messiness – thereby taking up the powerful impetus of the broader practice turn in interdisciplinary science studies and STS (Science and Technology Studies (11)) (12–14), which have recently also re-oriented archaeological self-observation, metatheory and epistemology (15). This perspective on the dawning big data age in archaeology and incurred changes in the status, nature and aims of type-thinking produces a number of important insights, which Lucas fruitfully discusses in relation to promises of ‘automation’ and ‘novelty’ as these feature centrally in the rhetorics and politics of the Third Science Revolution. With regard to automation, Lucas makes the important point that machine or computer work as championed by big data proponents cannot adequately be qualified or understood if we approach the issue from a purely time-saving perspective. The question we have to ask instead is what work do machines actually do and how do they change the dynamics of archaeological knowledge production in the process? In this optic, automation and acceleration achieved through computation appear to make most sense in the realm of the uncontroversial, in terms of “reproducing an accepted way of doing things” as Lucas says, and this is precisely what can be observed in archaeological practice as well. The ramifications of this at first sight innocent realization are far-reaching, however. If we accept the noncontroversial claim that automation partially bypasses the need for specialists through the reproduction of already “pre-determined outputs”, automated typologization would primarily be useful in dealing with and synthesizing larger amounts of information by sorting artefacts into already accepted types rather than create novel types or typologies. If we identity the big data promise at least in part with automation, even the detection of novel patterns in any archaeological dataset used to construct new types cannot escape the fact that this novelty is always already prefigured in the data structure devised. The success of ‘supervised learning’ in AI-based approaches illustrates this. Automation thus simply shifts the epistemological burden back to data selection and preparation but this is rarely realized, precisely because of the tacit requirement of broad non-contentiousness. Minimally, therefore, big data approaches ironically curtail their potential for novelty by adhering to conventional data treatment and input formats, rarely problematizing the issue of data construction and the contested status of (observational) data themselves. By contrast, they seek to shield themselves against such attempts and tend to retain a tacit universalism as to the nature of archaeological data. Only in this way is it possible to claim that such data have the capacity to “speak for themselves”. To use a concept borrowed from complexity theory, archaeological automation-based type-construction that relies on supposedly basal, incontrovertible data inputs can only ever hope to achieve ‘weak emergence’ (16) – ‘strong emergence’ and therefore true, radical novelty require substantial re-thinking of archaeological data and how to construct them. This is not merely a technical question as sometimes argued by computational archaeologies – for example with reference to specifically developed, automated object tracing procedures – as even such procedures cannot escape the fundamental question of typology: which kind of observations to draw on in order to explore what aspects of artefactual variability (and why). The focus on readily measurable features – classically dimensions of artefactual form – principally evades the key problem of typology and ironically also reduces the complexity of artefactual realities these approaches assert to take seriously. The rise of computational approaches to typology therefore reintroduces the problem of universalism and, as it currently stands, reduces the complexity of observational data potentially relevant for type-construction in order to enable to exploration of the complexity of pattern. It has often been noted that this larger configuration promotes ‘data fetishism’ and because of this alienates practitioners from the archaeological record itself – to speak with Marxist theory that Lucas briefly touches upon. We will briefly return to the notion of ‘distance’ below because it can be described as a symptomatic research-logical trope (and even a goal) in this context of inquiry. In total, then, the aspiration for novelty is ultimately difficult to uphold if computational archaeologies refuse to engage in fundamental epistemological and reflexive self-engagement. As Lucas poignantly observes, the most promising locus for novelty is currently probably not to be found in the capacity of the machines or algorithms themselves, but in the modes of collaboration that become possible with archaeological practitioners and specialists (and possibly diverse other groups of knowledge stakeholders). In other words, computers, supercomputers and AI technologies do not revolutionize our knowledge because of their superior computational and pattern-detection capacities – or because of some mysterious ‘superintelligence’ – but because of the specific ‘division of labour’ they afford and the cognitive challenge(s) they pose. Working with computers and AI also often requires to ask new questions or at least to adapt the questions we ask. This can already be seen on the ground, when we pay attention to how machine epistemologies are effectively harnessed in archaeological practice (and is somewhat ironic given that the promise of computational archaeology is often identified with its potential to finally resolve "long-standing (old) questions"). The Third Science Revolution likely prompts a consequential transformation in the structural and material conditions of the kinds of ‘distributed’ processes of knowledge production that STS have documented as characteristic for scientific discoveries and knowledge negotiations more generally (14, 17, 18). This ongoing transformation is thus expected not only to promote new specializations with regard to the utilization of the respective computing infrastructures emerging within big data ecologies but equally to provoke increasing demand for new ways of conceptualizing observations and to reformulate the theoretical needs and goals of typology in archaeology. The rediscovery of reflexivity as an epistemic virtue within big data debates would be an important step into this direction, as it would support the shared goal of achieving true epistemic novelty, which, as Lucas points out, is usually not more than an elusive self-declaration. Big data infrastructures require novel modes of human-machine synergy, which simply cannot be developed or cultivated in an atheoretical and/or epistemological disinterested space. Lucas’ exploration ultimately prompts us to ask big questions (again), and this is why this is an important contribution. The elephant in the room, of course, is the overly strong notion of objectivity on which much computational archaeology is arguably premised – linked to the vow to eventually construct ‘objective typologies’. This proclivity, however, re-tables all the problematic debates of the 1960s and – to speak with the powerful root metaphor of the machine fueling much of causal-mechanistic science (19, 20) – is bound to what A. Wylie (21) and others have called the ‘view from nowhere’. Objectivity, in this latter view, is defined by the absence of positionality and subjectivity – chiefly human subjectivity – and the promise of the machine, and by extension of computational archaeology, is to purify and thus to enhance processes of knowledge production by minimizing human interference as much as possible. The distancing of the human from actual processes of data processing and inference is viewed as positive and sometimes even as an explicit goal of scientific development. Interestingly, alienation from the archaeological record is framed as an epistemic virtue here, not as a burden, because close connection with (or even worse, immersion in) the intricacies of artefacts and archaeological contexts supposedly aggravates the problem of bias. The machine, in this optic, is framed as the gatekeeper to an observer-independent reality – which to the backdoor often not only re-introduces Platonian/Aristotelian pledges to a quasi-eternal fabric of reality that only needs to be “discovered” by applying the right (broadly nonhuman) means, it is also largely inconsistent with defendable and currently debated conceptions of scientific objectivity that do not fall prey to dogma. Furthermore, current discussions on the open AI ChatGPT have exposed the enormous and still under-reflected dangers of leaning into radical renderings of machine epistemology: precisely because of the principles of automation and the irreducible theory-ladenness of all data, ecologies such as ChatGPT tend to reinforce the tacit epistemological background structures on which they operate and in this way can become collaborators in the legitimization and justification of the status quo (which again counteracts the potential for novelty) – they reproduce supposedly established patterns of thought. This is why, among other things, machines and AI can quickly become perpetuators of parochial and neocolonial projects – their supposed authority creates a sense of impartiality that shields against any possible critique. With Lucas, we can thus perhaps cautiously say that what is required in computational archaeology is to defuse the authority of the machine in favour of a new community archaeology that includes machines as (fallible) co-workers. Radically put, computers and AI should be recognized as subjects themselves, and treated as such, with interesting perspectives on team science and collaborative practice.

Bibliography 1. Lucas, G. (2022). Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology. https:/doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7620824. 2. Kristiansen, K. (2014). Towards a New Paradigm? The Third Science Revolution and its Possible Consequences in Archaeology. Current Swedish Archaeology 22, 11–34. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2014.01. 3. Kristiansen, K. (2022). Archaeology and the Genetic Revolution in European Prehistory. Elements in the Archaeology of Europe. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009228701 4. Eisenhower, M. S. (1964). The Third Scientific Revolution. Science News 85, 322/332. https://www.sciencenews.org/archive/third-scientific-revolution. 5. The ‘Third Science Revolution’ in Archaeology. http://www.eaa2017maastricht.nl/theme4 (March 16, 2023). 6. Ribeiro, A. (2019). Science, Data, and Case-Studies under the Third Science Revolution: Some Theoretical Considerations. Current Swedish Archaeology 27, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2019.06 7. Samida, S. (2019). “Archaeology in times of scientific omnipresence” in Archaeology, History and Biosciences: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, pp. 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110616651 8. Sørensen, T. F.. (2017). The Two Cultures and a World Apart: Archaeology and Science at a New Crossroads. Norwegian Archaeological Review 50, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2017.1367031 9. Anderson, C. (2008). The end of theory: The data deluge makes the scientific method obsolete. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/. 10. Gattiglia, G. (2015). Think big about data: Archaeology and the Big Data challenge. Archäologische Informationen 38, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.11588/ai.2015.1.26155 11. Hackett, E. J. (2008). The handbook of science and technology studies, Third edition, MIT Press/Society for the Social Studies of Science. 12. Ankeny, R., Chang, H., Boumans, M. and Boon, M. (2011). Introduction: philosophy of science in practice. Euro Jnl Phil Sci 1, 303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-011-0036-4 13. Soler, L., Zwart, S., Lynch, M., Israel-Jost, V. (2014). Science after the Practice Turn in the Philosophy, History, and Social Studies of Science, Routledge. 14. Latour, B. and Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: the construction of scientific facts, Princeton University Press. 15. Chapman, R. and Wylie, A. (2016) Evidential reasoning in archaeology, Bloomsbury Academic. 16. Greve, J. and Schnabel, A. (2011). Emergenz: zur Analyse und Erklärung komplexer Strukturen, Suhrkamp. 17. Shapin, S., Schaffer, S. and Hobbes, T. (1985). Leviathan and the air-pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life, including a translation of Thomas Hobbes, Dialogus physicus de natura aeris by Simon Schaffer, Princeton University Press. 18. Galison, P. L. and Stump, D. J. (1996).The Disunity of Science: Boundaries, Contexts, and Power, Stanford University Press. 19. Pepper, S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print, University of California Press. 20. Hussain, S. T. (2019). The French-Anglophone divide in lithic research: A plea for pluralism in Palaeolithic Archaeology, Open Access Leiden Dissertations. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/69812 21. A. Wylie, A. (2015). “A plurality of pluralisms: Collaborative practice in archaeology” in Objectivity in Science, pp. 189-210, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14349-1_10 | Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology | Gavin Lucas | <p>In this paper, I will explore some of the implications of machine learning for archaeological method and theory. Against a back-drop of the rise of Big Data and the Third Science Revolution, what lessons can be drawn from the use of new digital... | Computational archaeology, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | Anonymous, Rachel Crellin | 2022-10-31 15:25:38 | View | |

23 Nov 2023

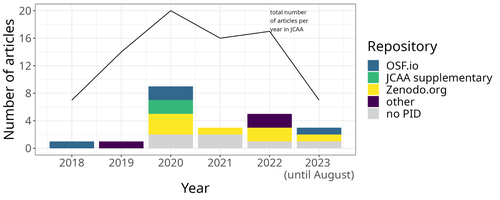

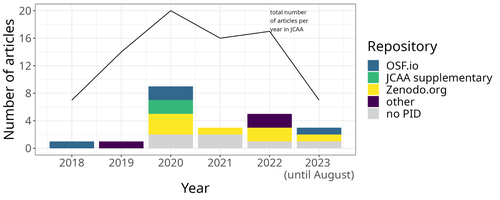

Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publicationSophie C Schmidt; Simon Maddison https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7966497Sharing Research Code in ArchaeologyRecommended by James Allison based on reviews by Thomas Rose, Joe Roe and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Thomas Rose, Joe Roe and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper “Percolation Package – From Script Sharing to Package Publication” by Sophie C. Schmidt and Simon Maddison (2023) describes the development of an R package designed to apply Percolation Analysis to archaeological spatial data. In an earlier publication, Maddison and Schmidt (2020) describe Percolation Analysis and provide case studies that demonstrate its usefulness at different spatial scales. In the current paper, the authors use their experience collaborating to develop the R package as part of a broader argument for the importance of code sharing to the research process. The paper begins by describing the development process of the R package, beginning with borrowing code from a geographer, refining it to fit archaeological case studies, and then collaborating to further refine and systematize the code into an R package that is more easily reusable by other researchers. As the review by Joe Roe noted, a strength of the paper is “presenting the development process as it actually happens rather than in an idealized form.” The authors also include a section about the lessons learned from their experience. Moving on from the anecdotal data of their own experience, the authors also explore code sharing practices in archaeology by briefly examining two datasets. One dataset comes from “open-archaeo” (https://open-archaeo.info/), an on-line list of open-source archaeological software maintained by Zack Batist. The other dataset includes articles published between 2018 and 2023 in the Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology. Schmidt and Maddison find that these two datasets provide contrasting views of code sharing in archaeology: many of the resources in the open-archaeo list are housed on Github, lack persistent object identifiers, and many are not easily findable (other than through the open-archaeo list). Research software attached to the published articles, on the other hand, is more easily findable either as a supplement to the published article, or in a repository with a DOI. The examination of code sharing in archaeology through these two datasets is preliminary and incomplete, but it does show that further research into archaeologists’ code-writing and code-sharing practices could be useful. Archaeologists often create software tools to facilitate their research, but how often? How often is research software shared with published articles? How much attention is given to documentation or making the software usable for other researchers? What are best (or good) practices for sharing code to make it findable and usable? Schmidt and Maddison’s paper provides partial answers to these questions, but a more thorough study of code sharing in archaeology would be useful. Differences among journals in how often they publish articles with shared code, or the effects of age, gender, nationality, or context of employment on attitudes toward code sharing seem like obvious factors for a future study to consider. Shared code that is easy to find and easy to use benefits the researchers who adopt code written by others, but code authors also have much to gain by sharing. Properly shared code becomes a citable research product, and the act of code sharing can lead to productive research collaborations, as Schmidt and Maddison describe from their own experience. The strength of this paper is the attention it brings to current code-sharing practices in archaeology. I hope the paper will also help improve code sharing in archaeology by inspiring more archaeologists to share their research code so other researchers can find and use (and cite) it. References Maddison, M.S. and Schmidt, S.C. (2020). Percolation Analysis – Archaeological Applications at Widely Different Spatial Scales. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 3(1), p.269–287. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcaa.54 Schmidt, S. C., and Maddison, M. S. (2023). Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publication, Zenodo, 7966497, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7966497 | Percolation Package - From script sharing to package publication | Sophie C Schmidt; Simon Maddison | <p>In this paper we trace the development of an R-package starting with the adaptation of code from a different field, via scripts shared between colleagues, to a published package that is being successfully used by researchers world-wide. Our aim... |  | Computational archaeology | James Allison | 2023-05-24 15:40:15 | View | |

28 Feb 2021

A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic AgeAlain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/7dq3b/Open data on beads, pendants, blanks from the Ceramic Age CaribbeanRecommended by Ben Marwick based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang

The paper 'A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age' by Queffelec et al. [1] presents a description of a dataset of nearly 5000 lapidary artefacts from over 100 sites. The data are dominated by beads and pendants, which are mostly made from Diorite, Turquoise, Carnelian, Amethyst, and Serpentine. The raw material data is especially valuable as many of these are not locally available on the island. This holds great potential for exchange network analysis. The data may be especially useful for investigating one of the fundamental questions of this region: whether the Cedrosan and Huecan are separate, little related developments, with different origins, or variants or a single tradition [2]. In addition to metric and technological details about the artefacts, the data include a variety of locational details, including coordinates, distance to coast, and altitude. This enables many opportunities for future spatial analysis and geostatistical modelling to understand human behaviours relating to ornament production, use, and discard. I recommend the authors make a minor revision to Table 1 (spatial coverage of the dataset) to make the column with the citations conform to the same citation style used in the rest of the text. I warmly commend the authors for making transparency and reproducibility a priority when preparing their manuscript. Their use of the R Markdown format for writing reproducible, dynamic documents [3] is highly impressive. This is an excellent example for others in the international archaeological science community to follow. The paper is especially useful for researchers who are new to R and R Markdown because of the elegant and accessible way the authors document their research here. [1] Queffelec, A., Fouéré, P. and Caverne, J.-B. 2021. A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age. SocArXiv, 7dq3b, ver. 4 Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/7dq3b [2] Reed, J. A. and Petersen, J. B. 2001. A comparison of Huecan and Cedrosan Saladoid ceramics at the Trants site, Montserrat. In Proceedings of the XVIIIth International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology (pp. 253-267). [3] Marwick, B. 2017. Computational Reproducibility in Archaeological Research: Basic Principles and a Case Study of Their Implementation. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24, 424–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-015-9272-9 | A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age | Alain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne | <p>Lapidary artifacts show an impressive abundance and diversity during the Ceramic period in the Caribbean islands, especially at the beginning of this period. Most of the raw materials used in this production do not exist naturally on the island... |  | Neolithic, North America, Raw materials, South America, Spatial analysis, Symbolic behaviours | Ben Marwick | 2020-11-13 23:52:34 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3DFlorian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269A valuable contribution to automated analysis of palaeolithic artefactsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper (Linsel/Bullenkamp/Mara 2024), the authors propose an automatic system for scar-ridge-pattern detection on palaeolithic artefacts based on Morse Theory. Scare-Ridge pattern recognition is a process that is usually done manually while creating a drawing of the object itself. Automatic systems to detect scars or ridges exist, but only a small amount of them is utilizing 3D data. In addition to the scar-ridges detection, the authors also experiment in automatically detecting the operational sequence, the temporal relation between scars and ridges. As a result, they can export a traditional drawing as well as graph models displaying the relationships between the scars and ridges. After an introduction to the project and the practice of documenting palaeolithic artefacts, the authors explain their procedure in automatising the analysis of scars and ridges as well as their temporal relation to each other on these artefacts. To illustrate the process, an open dataset of lithic artefacts from the Grotta di Fumane, Italy, was used and 62 artefacts selected. To establish a Ground Truth, the artefacts were first annotated manually. The authors then continue to explain in detail each step of the automated process that follows and the results obtained. In the second part of the paper, the results are presented. First the results of the segmentation process shows that the average percentage of correctly labelled vertices is over 91%, which is a remarkable result. The graph modelling however shows some more difficulties, which the authors are aware of. To enhance the process, the authors rightfully aim to include datasets of experimental archaeology in the future. They also aim to develop a way of detecting the operational sequence automatically and precisely. This paper has great potential as it showcases exactly what Digital and Computational Archaeology is about: The development of new digital methods to enhance the analysis of archaeological data. While this procedure is still in development, the authors were able to present a valuable contribution to the automatization of analytical archaeology. By creating a step towards the machine-readability of this data, they also open up the way to further steps in machine learning within Archaeology. BibliographyLinsel, F., Bullenkamp, J. P., and Mara, H. (2024). Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D, Zenodo, 8296269, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269 | Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D | Florian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara | <p>Motivated by the concept of combining the archaeological practice of creating lithic artifact drawings with the potential of 3D mesh data, our goal in this project is not only to analyze the shape at the artifact level, but also to enable a mor... | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Upper Palaeolithic | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-09-01 23:03:59 | View | ||

20 Jul 2022

Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, IsraelNimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4New zooarchaeological data from the Upper Palaeolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2, IsraelRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio

The Levantine Corridor is considered a crossing point to Eurasia and one of the main areas for detecting population flows (and their associated cultural and economic changes) during the Pleistocene. This area could have been closed during the most arid periods, giving rise to processes of population isolation between Africa and Eurasia and intermittent contact between Eurasian human communities [1,2]. Zooarchaeological studies of the early Upper Palaeolithic assemblages constitute an important source of knowledge about human subsistence, making them central to the debate on modern behaviour. The Early Upper Palaeolithic sequence in the Levant includes two cultural entities – the Early Ahmarian and the Levantine Aurignacian. This latter is dated to 39-33 ka and is considered a local adaptation of the European Aurignacian techno-complex. In this work, the authors present a zooarchaeological study of the Nahal Rahaf 2 (ca. 35 ka) archaeological site in the southern Judean Desert in Israel [3]. Zooarchaeological data from the early Upper Paleolithic desert regions of the southern Levant are not common due to preservation problems of non-lithic finds. In the case of Nahal Rahaf 2, recent excavation seasons brought to light a stratigraphical sequence composed of very well-preserved archaeological surfaces attributed to the 'Arkov-Divshon' cultural entity, which is associated with the Levantine Aurignacian. This study shows age-specific caprine (Capra cf. Capra ibex) hunting on prime adults and a generalized procurement of gazelles (Gazella cf. Gazella gazella), which seem to have been selectively transported to the site and processed for within-bone nutrients. An interesting point to note is that the proportion of goats increases along the stratigraphic sequence, which suggests to the authors a specialization in the economy over time that is inversely related to the occupational intensity of use of the site. It is also noteworthy that the materials represent a large sample compared to previous studies from the Upper Paleolithic of the Judean Desert and Negev. In summary, this manuscript contributes significantly to the study of both the palaeoenvironment and human subsistence strategies in the Upper Palaeolithic and provides another important reference point for evaluating human hunting adaptations in the arid regions of the southern Levant. References [1] Bermúdez de Castro, J.-L., Martinon-Torres, M. (2013). A new model for the evolution of the human pleistocene populations of Europe. Quaternary Int. 295, 102-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.036 [2] Bar-Yosef, O., Belfer-Cohen, A. (2010). The Levantine Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic. In Garcea, E.A.A. (Ed), South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples Between 130,000 and 10,000 Years Ago. Oxbow Books, pp. 144-167. [3] Marom, N., Gnezdilov, D. L., Shafir, R., Barzilai, O. and Shemer, M. (2022). Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel. BioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492258, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4 | Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel | Nimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer | <p>Nahal Rahaf 2 (NR2) is an Early Upper Paleolithic (ca. 35 kya) rock shelter in the southern Judean Desert in Israel. Two excavation seasons in 2019 and 2020 revealed a stratigraphical sequence composed of intact archaeological surfaces attribut... |  | Upper Palaeolithic, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Joana Gabucio | 2022-05-19 06:16:47 | View |

29 Jan 2024

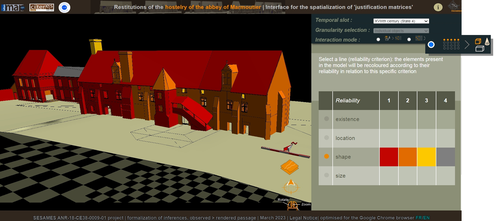

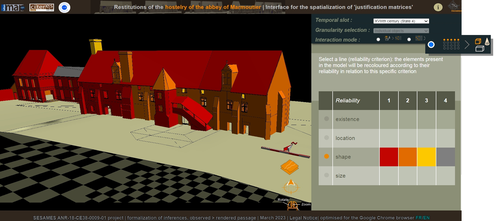

Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept researchJ.Y Blaise, I.Dudek, L.Bergerot, G.Simon https://zenodo.org/record/79831633D Models, Knowledge and Visualization: a prototype for 3D virtual models according to plausible criteriaRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Robert Bischoff and Louise TharandtThe construction of 3D realities is deeply embedded in archaeological practices. From sites to artifacts, archaeology has dedicated itself to creating digital copies for the most varied purposes. The paper “Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's 3 scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research” (Jean-Yves et al 2024) represents an advance, in the sense that it does not just deal with a three-dimensional theory for archaeological practice, but rather offers proposals regarding the epistemic component, how it is possible to represent knowledge through the workflow of 3D virtual reconstructions themselves. The authors aim to unite three main axes - knowledge modeling, visual encoding and 3D content reuse - (Jean-Yves et al 2024: 2), which, for all intents and purposes, form the basis of this article. With regard to the first aspect, this work questions how it is possible to transmit the knowledge we want to a 3D model and how we can optimize this epistemic component. A methodology based on plausibility criteria is offered, which, for the archaeological field, offers relevant space for reflection. Given our inability to fully understand the object or site that is the subject of the 3D representation, whether in space or time, building a method based on probabilistic categories is probably one of the most realistic approaches to the realities of the past. Thus, establishing a plausibility criterion allows the user to question the knowledge that is transmitted through the representation, and can corroborate or refute it in future situations. This is because the role of reusing these models is of great interest to the authors, a perfectly justifiable sentiment, as it encourages a critical view of scientific practices. Visual encoding is, in terms of its conjunction with knowledge practices, a key element. The notion of simplicity under Maeda's (2006) design principles not only represents a way of thinking that favors operability, but also a user-friendly design in the prototype that the authors have created. This is also visible when it comes to the reuse of parts of the models, in a chronological logic: adapting the models based on architectural elements that can be removed or molded is a testament to intelligent design, whereby instead of redoing models in their entirety, they are partially used for other purposes. All these factors come together in the final prototype, a web application that combines relational databases (RDBMS) with a data mapper (MassiveJS), using the PHP programming language. The example used is the Marmoutier Abbey hostelry, a centuries-old building which, according to the sources presented, has evolved architecturally over several centuries ((Jean-Yves et al 2024: 8). These states of the building are represented visually through architectural elements based on their existence, location, shape and size, always in terms of what is presented as being plausible. This allows not only the creation of a matrix in which various categories are related to various architectural elements, but also a visual aid, through a chromatic spectrum, of the plausibility that the authors are aiming for. In short, this is an article that seeks to rethink the degree of knowledge we can obtain through 3D visualizations and that does not take models as static, but rather realities that must be explored, recycled and reinterpreted in the light of different data, users and future research. For this reason, it is a work of great relevance to theoretical advances in 3D modeling adapted to archaeology.

References Blaise, J.-Y., Dudek, I., Bergerot, L. and Gaël, S. (2024). Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research, Zenodo, 7983163, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10496540 John Maeda. (2006). The Laws of Simplicity. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. | Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research | J.Y Blaise, I.Dudek, L.Bergerot, G.Simon | <p> 3D virtual reconstructions have become over the last decades a classical mean to communicate about analysts’ visions concerning past stages of development of an edifice or a site. However, they still today remain quite often a one-s... |  | Computational archaeology, Spatial analysis | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-05-30 00:43:03 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer