Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

04 Oct 2023

IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A "para-description"Hagmann, Dominik; Reiner, Franziska https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5vwg8The IUENNA project: integrating old data and documentation for future archaeologyRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Nina Richards and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Nina Richards and 3 anonymous reviewers

This recommended paper on the IUENNA project (Hagmann and Reiner 2023) is not a paper in the traditional sense, but it is a reworked version of a project proposal. It is refreshing to read about a project that has just started and see what the aims of the project are. This ties in with several open science ideas and standards (e.g. Brinkman et al. 2023). I am looking forward to see in a few years how the authors managed to reach the aims and goals of the project. The IUENNA project deals with the legacy data and old excavations on the Hemmaberg and in the Jauntal. Archaeological research in this small, but important region, has taken place for more than a century, revealing material from over 2000 years of human history. The Hemmaberg is well known for its late antique and early medieval structures, such as roads, villas and the various churches. The wider Jauntal reveals archaeological finds and features dating from the Iron Age to the recent past. The authors of the paper show the need to make sure that the documentation and data of these past archaeological studies and projects will be accessible in the future, or in their own words: "Acute action is needed to systematically transition these datasets from physical filing cabinets to a sustainable, networked virtual environment for long-term use" (Hagmann and Reiner 2023: 5). The papers clearly shows how this initiative fits within larger developments in both Digital Archaeology and the Digital Humanities. In addition, the project is well grounded within Austrian archaeology. While the project ties in with various international standards and initiatives, such as Ariadne (https://ariadne-infrastructure.eu/) and FAIR-data standards (Wilkinson et al. 2016, 2019), it would benefit from the long experience institutes as the ADS (https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/) and DANS (see Data Station Archaeology: https://dans.knaw.nl/en/data-stations/archaeology/) have on the storage of archaeological data. I would also like to suggest to have a look at the Dutch SIKB0102 standard (https://www.sikb.nl/datastandaarden/richtlijnen/sikb0102) for the exchange of archaeological data. The documentation is all in Dutch, but we wrote an English paper a few years back that explains the various concepts (Boasson and Visser 2017). However, these are a minor details or improvements compared to what the authors show in their project proposal. The integration of many standards in the project and the use of open software in a well-defined process is recommendable. The IUENNA project is an ambitious project, which will hopefully lead to better insights, guidelines and workflows on dealing with legacy data or documentation. These lessons will hopefully benefit archaeology as a discipline. This is important, because various (European) countries are dealing with similar problem, since many excavations of the past have never been properly published, digitalized or deposited. In the Netherlands, for example, various projects dealt with publication of legacy excavations in the Odyssee-project (https://www.nwo.nl/onderzoeksprogrammas/odyssee). This has led to the publication of various books and datasets (24) (https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:34359), but there are still many datasets (8) missing from the various projects. In addition, each project followed their own standards in creating digital data, while IUENNA will make an effort to standardize this. There are still more than 1000 Dutch legacy excavations still waiting to be published and made into a modern dataset (Kleijne 2010) and this is probably the case in many other countries. I sincerely hope that a successful end of IUENNA will be an inspiration for other regions and countries for future safekeeping of legacy data. References Boasson, W and Visser, RM. 2017 SIKB0102: Synchronizing Excavation Data for Preservation and Re-Use. Studies in Digital Heritage 1(2): 206–224. https://doi.org/10.14434/sdh.v1i2.23262 Brinkman, L, Dijk, E, Jonge, H de, Loorbach, N and Rutten, D. 2023 Open Science: A Practical Guide for Early-Career Researchers https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7716153 Hagmann, D and Reiner, F. 2023 IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A ‘para-description’. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5vwg8 Kleijne, JP. 2010. Odysee in de breedte. Verslag van het NWO Odyssee programma, kortlopend onderzoek: ‘Odyssee, een oplossing in de breedte: de 1000 onuitgewerkte sites, die tot een substantiële kennisvermeerdering kunnen leiden, digitaal beschikbaar!’ ‐ ODYK‐09‐13. Den Haag: E‐depot Nederlandse Archeologie (EDNA). https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-z25-g4jw Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Aalbersberg, IjJ, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, ’t Hoen, PAC, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Velterop, J, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2016 The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1): 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Jan Aalbersberg, I, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, Hoen, PAC ’t, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Jan Velterop, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2019 Addendum: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 6(1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0009-6

| IUENNA – openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology: A "para-description" | Hagmann, Dominik; Reiner, Franziska | <p>The Go!Digital 3.0 project IUENNA – an acronym for “openIng the soUthErn jauNtal as a micro-regioN for future Archaeology” – embraces a comprehensive open science methodology. It focuses on the archaeological micro-region of the Jauntal Valley ... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Computational archaeology | Ronald Visser | 2023-04-06 13:36:16 | View | |

29 Aug 2023

Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious GamesTsaknaki, Electra; Anastasovitis, Eleftherios; Georgiou, Georgia; Alagialoglou, Kleopatra; Mavrokostidou, Maria; Kartsiakli, Vasiliki; Aidonis, Asterios; Protopsalti, Tania; Nikolopoulos, Spiros; Kompatsiaris, Ioannis https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981323AR and VR Gamification as a proof-of-conceptRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Sophie C. Schmidt and Tine Rassalle based on reviews by Sophie C. Schmidt and Tine Rassalle

Tsaknaki et al. (2023) discuss a work-in-progress project in which the presentation of Cultural Heritage is communicated using Serious Games techniques in a story-centric immersive narration instead of an exhibit-centered presentation with the use of Gamification, Augmented and Virtual Reality technologies. In the introduction the authors present the project called ECHOES, in which knowledge about the past of Thessaloniki, Greece is planned to be processed as an immersive and interactive experience. After presenting related work and the methodology, the authors describe the proposed design of the Serious Game and close the article with a discussion and conclusions. The paper is interesting because it highlights an ongoing process in the realm of the visualization of Cultural Heritage (see for example Champion 2016). The process described by the authors on how to accomplish this by using Serious Games, Gamification, Augmented and Virtual Reality is promising, although still hypothetical as the project is ongoing. It remains to be seen if the proposed visuals and interactive elements will work in the way intended and offer users an immersive experience after all. A preliminary questionnaire already showed that most of the respondents were not familiar with these technologies (AR, VR) and in my experience these numbers only change slowly. One way to overcome the technological barrier however might be the gamification of the experience, which the authors are planning to implement. I decided to recommend this article based on the remarks of the two reviewers, which the authors implemented perfectly, as well as my own evaluation of the paper. Although still in progress it seems worthwhile to have this article as a basis for discussion and comparison to similar projects. However, the article did not mention the possible longevity of data and in which ways the usability of the Serious Game will be secured for long-term storage. One eminent problem in these endeavors is, that we can read about these projects, but never find them anywhere to test them ourselves (see for example Gabellone et al. 2016). It is my intention with this review and the recommendation, that the ECHOES project will find a solution for this problem and that we are not only able to read this (and forthcoming) article(s) about the ECHOES project, but also play the Serious Game they are proposing in the near and distant future. References

Gabellone, Francesco, Antonio Lanorte, Nicola Masini, und Rosa Lasaponara. 2016. „From Remote Sensing to a Serious Game: Digital Reconstruction of an Abandoned Medieval Village in Southern Italy“. Journal of Cultural Heritage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.01.012 Tsaknaki, Electra, Anastasovitis, Eleftherios, Georgiou, Georgia, Alagialoglou, Kleopatra, Mavrokostidou, Maria, Kartsiakli, Vasiliki, Aidonis, Asterios, Protopsalti, Tania, Nikolopoulos, Spiros, and Kompatsiaris, Ioannis. (2023). Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious Games, Zenodo, 7981323, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981323 | Designing Stories from the Grave: Reviving the History of a City through Human Remains and Serious Games | Tsaknaki, Electra; Anastasovitis, Eleftherios; Georgiou, Georgia; Alagialoglou, Kleopatra; Mavrokostidou, Maria; Kartsiakli, Vasiliki; Aidonis, Asterios; Protopsalti, Tania; Nikolopoulos, Spiros; Kompatsiaris, Ioannis | <p>The main challenge of the current digital transition is to utilize computing media and cutting-edge technologyin a more meaningful way, which would make the archaeological and anthropological research outcomes relevant to a heterogeneous audien... |  | Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Europe | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-05-29 13:19:46 | View | |

26 Mar 2024

What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery.Philippe Boissinot https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433Abstract and Concrete – Querying the Metaphysics and Geometry of Pottery ClassificationRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

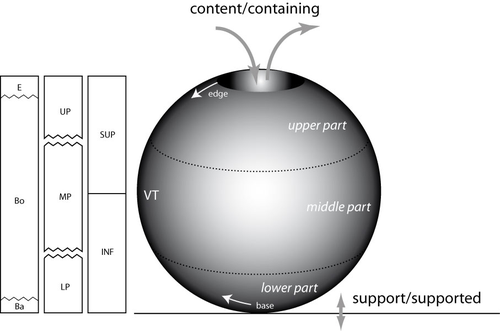

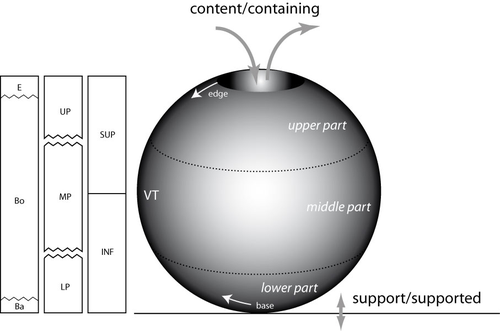

“What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery” by P. Boissinot (1) is a timely contribution to broader theoretical reflections on classification and ordering practices in archaeology, including type-construction and justification. Boissinot rightly reminds us that engagement with the type concept always touches upon the uneasy relationship between the abstract and the concrete, alternatively cast as the ongoing struggle in knowledge production between idealization and particularization. Types are always abstract and as such both ‘more’ and ‘less’ than the concrete objects they refer to. They are ‘more’ because they establish a higher-order identity of variously heterogeneous, concrete objects and they are ‘less’ because they necessarily reduce the richness of the concrete and often erase it altogether. The confusion that types evoke in archaeology and elsewhere has therefore a lot to do with the fact that types are simply not spatiotemporally distinct particulars. As abstract entities, types so almost automatically re-introduce the question of universalism but they do not decide this question, and Boissinot also tentatively rejects such ambitions. In fact, with Boissinot (1) it may be said that universality is often precisely confused with idealization, which is indispensable to all archaeological ordering practices. Idealization, increasingly recognized as an important epistemic operation in science (2, 3), paradoxically revolves around the deliberate misrepresentation of the empirical systems being studied, with models being the paradigm cases (4). Models can go so far as to assume something strictly false about the phenomena under consideration in order to advance their epistemic goals. In the words of Angela Potochnik (5), ‘the role of idealization in securing understanding distances understanding from truth but […] this understanding nonetheless gives rise to scientific knowledge’. The affinity especially to models may in part explain why types are so controversial and are often outright rejected as ‘real’ or ‘useful’ by those who only recognize the existence of concrete particulars (nominalism). As confederates of the abstract, types thus join the ranks of mathematics and geometry, which the author identifies as prototypical abstract systems. Definitions are also abstract. According to Boissinot (1), they delineate a ‘position of limits’, and the precision and rigorousness they bring comes at the cost of subjectivity. This unites definitions and types, as both can be precise and clear-cut but they can never be strictly singular or without alternative – in order to do so, they must rely on yet another higher-order system of external standards, and so ad infinitum. Boissinot (1) advocates a mathematical and thus by definition abstract approach to archaeological type-thinking in the realm of pottery, as the abstractness of this approach affords relatively rigorous description based on the rules of geometry. Importantly, this choice is not a mysterious a priori rooted in questionable ideas about the supposed superiority of such an approach but rather is the consequence of a careful theoretical exploration of the particularities (domain-specificities) of pottery as a category of human practice and materiality. The abstract thus meets the concrete again: objects of pottery, in sharp contrast to stone artefacts for example, are the product of additive processes. These processes, moreover, depend on the ‘fusion’ of plastic materials and the subsequent fixation of the resulting configuration through firing (processes which, strictly speaking, remove material, such as stretching, appear to be secondary vis-à-vis global shape properties). Because of this overriding ‘fusion’ of pottery, the identification of parts, functional or otherwise, is always problematic and indeterminate to some extent. As products of fusion, parts and wholes represent an integrated unity, and this distinguishes pottery from other technologies, especially machines. The consequence is that the presence or absence of parts and their measurements may not be a privileged locus of type-construction as they are in some biological contexts for example. The identity of pottery objects is then generally bound to their fusion. As a ‘plastic montage’ rather than an assembly of parts, individual parts cannot simply be replaced without threatening the identity of the whole. Although pottery can and must sometimes be repaired, this renders its objects broadly morpho-static (‘restricted plasticity’) rather than morpho-dynamic, which is a condition proper to other material objects such as lithic (use and reworking) and metal artefacts (deformation) but plays out in different ways there. This has a number of important implications, namely that general shape and form properties may be expected to hold much more relevant information than in technological contexts characterized by basal modularity or morpho-dynamics. It is no coincidence that ‘fusion’ is also emphasized by Stephen C. Pepper (6) as a key category of what he calls contextualism. Fusion for Pepper pays dividends to the interpenetration of different parts and relations, and points to a quality of wholes which cannot be reduced any further and integrates the details into a ‘more’. Pepper maintains that ‘fusion, in other words, is an agency of simplification and organization’ – it is the ‘ultimate cosmic determinator of a unit’ (p. 243-244, emphasis added). This provides metaphysical reasons to look at pottery from a whole-centric perspective and to foreground the agency of its materiality. This is precisely what Boissinot (1) does when he, inspired by the great techno-anthropologist François Sigaut (7), gestures towards the fact that elementarily a pot is ‘useful for containing’. He thereby draws attention not to the function of pottery objects but to what pottery as material objects do by means of their material agency: they disclose a purposive tension between content and container, the carrier and carried as well as inclusion and exclusion, which can also be understood as material ‘forces’ exerted upon whatever is to be contained. This, and not an emic reading of past pottery use, leads to basic qualitative distinctions between open and closed vessels following Anna O. Shepard’s (8) three basic pottery categories: unrestricted, restricted, and necked openings. These distinctions are not merely intuitive but attest to the object-specificity of pottery as fused matter. This fused dimension of pottery also leads to a recognition that shapes have geometric properties that emerge from the forced fusion of the plastic material worked, and Boissinot (1) suggests that curvature is the most prominent of such features, which can therefore be used to describe ‘pure’ pottery forms and compare abstract within-pottery differences. A careful mathematical theorization of curvature in the context of pottery technology, following George D. Birkhoff (9), in this way allows to formally distinguish four types of ‘geometric curves’ whose configuration may serve as a basis for archaeological object grouping. The idealization involved in this proposal is not accidental but deliberately instrumental – it reminds us that type-thinking in archaeology cannot escape the abstract. It is notable here that the author does not suggest to simply subject total pottery form to some sort of geometric-morphometric analysis but develops a proposal that foregrounds a limited range of whole-based geometric properties (in contrast to part-based) anchored in general considerations as to the material specificity of pottery as quasi-species of objects. As Boissinot (1) notes himself, this amounts to a ‘naturalization’ of archaeological artefacts and offers somewhat of an alternative (a third way) to the old discussion between disinterested form analysis and functional (and thus often theory-dependent) artefact groupings. He thereby effectively rejects both of these classic positions because the first ignores the particularities of pottery and the real function of artefacts is in most cases archaeologically inaccessible. In this way, some clear distance is established to both ethnoarchaeology and thing studies as a project. Attending to the ‘discipline of things’ proposal by Bjørnar Olsen and others (10, 11), and by drawing on his earlier work (12), Boissinot interestingly notes that archaeology – never dealing with ‘complete societies’ – could only be ‘deficient’. This has mainly to do with the underdetermination of object function by the archaeological record (and the confusion between function and functionality) as outlined by the author. It seems crucial in this context that Boissinot does not simply query ‘What is a thing?’ as other thing-theorists have previously done, but emphatically turns this question into ‘In what way is it not the same as something else?’. He here of course comes close to Olsen’s In Defense of Things insofar as the ‘mode of being’ or the ‘ontology’ of things is centred. What appears different, however, is the emphasis on plurality and within-thing heterogeneity on the level of abstract wholes. With Boissinot, we always have to speak of ontologies and modes of being and those are linked to different kinds of things and their material specificities. Theorizing and idealizing these specificities are considered central tasks and goals of archaeological classification and typology. As such, this position provides an interesting alternative to computational big-data (the-more-the-better) approaches to form and functionally grounded type-thinking, yet it clearly takes side in the debate between empirical and theoretical type-construction as essential object-specific properties in the sense of Boissinot (1) cannot be deduced in a purely data-driven fashion. Boissinot’s proposal to re-think archaeological types from the perspective of different species of archaeological objects and their abstract material specificities is thought-provoking and we cannot stop wondering what fruits such interrogations would bear in relation to other kinds of objects such as lithics, metal artefacts, glass, and so forth. In addition, such meta-groupings are inherently problematic themselves, and they thus re-introduce old challenges as to how to separate the relevant super-wholes, technological genesis being an often-invoked candidate discriminator. The latter may suggest that we cannot but ultimately circle back on the human context of archaeological objects, even if we, for both theoretical and epistemological reasons, wish to embark on strictly object-oriented archaeologies in order to emancipate ourselves from the ‘contamination’ of language and in-built assumptions.

Bibliography 1. Boissinot, P. (2024). What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery, Zenodo, 7429330, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433 2. Fletcher, S.C., Palacios, P., Ruetsche, L., Shech, E. (2019). Infinite idealizations in science: an introduction. Synthese 196, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02069-6 3. Potochnik, A. (2017). Idealization and the aims of science (University of Chicago Press). https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226507194.001.0001 4. J. Winkelmann, J. (2023). On Idealizations and Models in Science Education. Sci & Educ 32, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00291-2 5. Potochnik, A. (2020). Idealization and Many Aims. Philosophy of Science 87, 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1086/710622 6. Pepper S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (University of California Press). 7. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l’analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d’études Technologiques En Préhistoire. Bilan et Perspectives (Association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques), pp. 21–34. 8. Shepard, A. O. (1956). Ceramics for the Archeologist (Carnegie Institution of Washington n° 609). 9. Birkhoff G. D. (1933). Aesthetic Measure (Harvard University Press). 10. Olsen, B. (2010). In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects (AltaMira Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/ept014 11. Olsen, B., Shanks, M., Webmoor, T., Witmore, C. (2012). Archaeology: the discipline of things (University of California Press). https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520954007 12. Boissinot, P. (2011). “Comment sommes-nous déficients ?” in L’archéologie Comme Discipline ? (Le Seuil), pp. 265–308. | What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery. | Philippe Boissinot | <p>The main question we want to ask here concerns the application of philosophical considerations on identity about artifacts of a particular kind (pottery). The purpose is the recognition of types and their classification, which are two of the ma... |  | Ceramics, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2022-12-13 15:04:45 | View | |

02 Nov 2020

Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case StudyJoseph Lewis https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/mxas2A probabilistic method for Least Cost Path calculation.Recommended by Otis Crandell based on reviews by Georges Abou Diwan and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper entitled “Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study” [1] submitted by J. Lewis presents an innovative approach to applying Least Cost Path (LCP) analysis to incorporate uncertainty of the Digital Elevation Model used as the topographic surface on which the path is calculated. The proposition of using Monte Carlo simulations to produce numerous LCP, each with a slightly different DEM included in the error range of the model, allows one to strengthen the method by proposing a probabilistic LCP rather than a single and arbitrary one which does not take into account the uncertainty of the topographic reconstruction. This new method is integrated in the R package leastcostpath [2]. The author tests the method using a Roman road built along a ridge in Cumbria, England. The integration of the uncertainty of the DEM, thanks to Monte Carlo simulations, shows that two paths could have the same probability to be the real LCP. One of them is indeed the path that the Roman road took. In particular, it is one of two possibilities of LCP in the south to north direction. This new probabilistic method therefore strengthens the reconstruction of past pathways, while also allowing new hypotheses to be tested, and, in this case study, to suggest that the northern part of the Roman road’s location was selected to help the northward movements. [1] Lewis, J., 2020. Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study. SocArXiv, mxas2, ver 17 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology, 10.31235/osf.io/mxas2. [2] Lewis, J., 2020. leastcostpath: Modelling Pathways and Movement Potential Within a Landscape. R package. Version 1.7.4. | Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study | Joseph Lewis | <p>The movement of past peoples in the landscape has been studied extensively through the use of Least Cost Path (LCP) analysis. Although methodological issues of applying LCP analysis in Archaeology have frequently been discussed, the effect of v... |  | Spatial analysis | Otis Crandell | Adam Green, Georges Abou Diwan | 2020-08-05 12:10:46 | View |

20 Dec 2020

For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente.Marco Carpentieri, Marta Arzarello https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/2ptjbInvestigating the opportunistic debitage – an experimental approachRecommended by Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by David Hérisson and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper “For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente” [1] submitted by M. Carpentieri and M. Arzarello is a welcome addition to a growing number of studies focusing on flaking methods showing little to no core preparation, e.g., [2–4]. These flaking methods are often overlooked or seen as ‘simple’, which, in a Middle Palaeolithic context, sometimes leads to a dichotomy of Levallois vs. non-Levallois debitage (e.g., see discussion in [2]). The authors address this topic by first providing a definition for ‘opportunistic debitage’, derived from the definition of the ‘Alternating Surfaces Debitage System’ (SSDA, [5]). At the core of the definition is the adaptation to the characteristics (e.g., natural convexities and quality) of the raw material. This is one main challenge in studying this type of debitage in a consistent way, as the opportunistic debitage leads to a wide range of core and flake morphologies, which have sometimes been interpreted as resulting from different technical behaviours, but which the authors argue are part of a same ‘methodological substratum’ [1]. This article aims to further characterise the ‘opportunistic debitage’. The study relies on four archaeological assemblages from Italy, ranging from the Lower to the Upper Pleistocene, in which the opportunistic debitage has been recognised. Based on the characteristics associated with the occurrence of the opportunistic debitage in these assemblages, an experimental replication of the opportunistic debitage using the same raw materials found at these sites was conducted, with the aim to gain new insights into the method. Results show that experimental flakes and cores are comparable to the ones identified as resulting from the opportunistic debitage in the archaeological assemblage, and further highlight the high versatility of the opportunistic method. One outcome of the experimental replication is that a higher flake productivity is noted in the opportunistic centripetal debitage, along with the occurrence of 'predetermined-like' products (such as déjeté points). This brings the authors to formulate the hypothesis that the opportunistic debitage may have had a role in the process that will eventually lead to the development of Levallois and Discoid technologies. How this articulates with for example current discussions on the origins of Levallois technologies (e.g., [6–8]) is an interesting research avenue. This study also touches upon the question of how the implementation of one knapping method may be influenced by the broader technological knowledge of the knapper(s) (e.g., in a context where Levallois methods were common vs a context where they were not). It makes the case for a renewed attention in lithic studies for flaking methods usually considered as less behaviourally significant. [1] Carpentieri M, Arzarello M. 2020. For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente. OSF Preprints, doi:10.31219/osf.io/2ptjb [2] Bourguignon L, Delagnes A, Meignen L. 2005. Systèmes de production lithique, gestion des outillages et territoires au Paléolithique moyen : où se trouve la complexité ? Editions APDCA, Antibes, pp. 75–86. Available: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00447352 [3] Arzarello M, De Weyer L, Peretto C. 2016. The first European peopling and the Italian case: Peculiarities and “opportunism.” Quaternary International, 393: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.005 [4] Vaquero M, Romagnoli F. 2018. Searching for Lazy People: the Significance of Expedient Behavior in the Interpretation of Paleolithic Assemblages. J Archaeol Method Theory, 25: 334–367. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9339-x [5] Forestier H. 1993. Le Clactonien : mise en application d’une nouvelle méthode de débitage s’inscrivant dans la variabilité des systèmes de production lithique du Paléolithique ancien. Paléo, 5: 53–82. doi:10.3406/pal.1993.1104 [6] Moncel M-H, Ashton N, Arzarello M, Fontana F, Lamotte A, Scott B, et al. 2020. Early Levallois core technology between Marine Isotope Stage 12 and 9 in Western Europe. Journal of Human Evolution, 139: 102735. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102735 [7] White M, Ashton N, Scott B. 2010. The emergence, diversity and significance of the Mode 3 (prepared core) technologies. Elsevier. In: Ashton N, Lewis SG, Stringer CB, editors. The ancient human occupation of Britain. Elsevier. Amsterdam, pp. 53–66. [8] White M, Ashton N. 2003. Lower Palaeolithic Core Technology and the Origins of the Levallois Method in North‐Western Europe. Current Anthropology, 44: 598–609. doi:10.1086/377653 | For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente. | Marco Carpentieri, Marta Arzarello | <p>The opportunistic debitage, originally adapted from Forestier’s S.S.D.A. definition, is characterized by a strong adaptability to local raw material morphology and its physical characteristics and it is oriented towards flake production. Its mo... |  | Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic | Alice Leplongeon | 2020-07-23 14:26:04 | View | |

02 Sep 2023

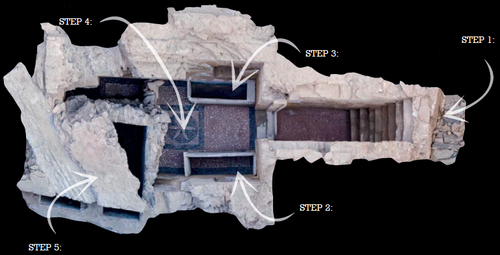

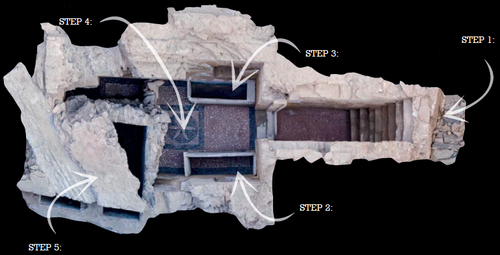

Research workflows, paradata, and information visualisation: feedback on an exploratory integration of issues and practices - MEMORIA ISDudek Iwona, Blaise Jean-Yves https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8311129Using information visualisation to improve traceability, transmissibility and verifiability in research workflowsRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Adéla Sobotkova and 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper “Research workflows, paradata, and information visualisation: feedback on an exploratory integration of issues and practices - MEMORIA IS” (Dudek & Blaise, 2023) describes a prototype of an information system developed to improve the traceability, transmissibility and verifiability of archaeological research workflows. A key aspect of the work with MEMORIA is to make research documentation and the workflows underpinning the conducted research more approachable and understandable using a series of visual interfaces that allow users of the system to explore archaeological documentation, including metadata describing the data and paradata that describes its underlying processes. The work of Dudek and Blaise address one of the central barriers to reproducibility and transparency of research data and propose a set of both theoretically and practically well-founded tools and methods to solve this major problem. From the reported work on MEMORIA IS, information visualisation and the proposed tools emerge as an interesting and potentially powerful approach for a major push in improving the traceability, transmissibility and verifiability of research data through making research workflows easier to approach and understand. In comparison to technical work relating to archaeological data management, this paper starts commendably with a careful explication of the conceptual and epistemic underpinnings of the MEMORIA IS both in documentation research, knowledge organisation and information visualisation literature. Rather than being developed on the basis of a set of opaque assumptions, the meticulous description of the MEMORIA IS and its theoretical and technical premises is exemplary in its transparence and richness and has potential for a long-term impact as a part of the body of literature relating to the development of archaeological documentation and documentation tools. While the text is sometimes fairly densely written, it is worth taking the effort to read it through. Another major strength of the paper is that it provides a rich set of examples of the workings of the prototype system that makes it possible to develop a comprehensive understanding of the proposed approaches and assess their validity. As a whole, this paper and the reported work on MEMORIA IS forms a worthy addition to the literature on and practical work for developing critical infrastructures for data documentation, management and access in archaeology. Beyond archaeology and the specific context of the discussed work discussed this paper has obvious relevance to comparable work in other fields. ReferencesDudek, I. and Blaise, J.-Y. (2023) Research workflows, paradata, and information visualisation: feedback on an exploratory integration of issues and practices - MEMORIA IS, Zenodo, 8252923, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8252923

| Research workflows, paradata, and information visualisation: feedback on an exploratory integration of issues and practices - MEMORIA IS | Dudek Iwona, Blaise Jean-Yves | <p>The paper presents an exploratory web information system developed as a reaction to practical and epistemological questions, in the context of a scientific unit studying the architectural heritage (from both historical sciences perspective, and... |  | Computational archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-02 12:50:39 | View | |

26 Mar 2024

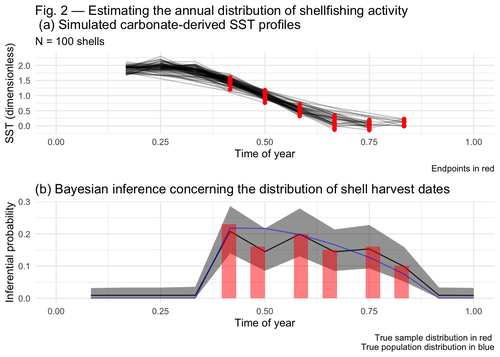

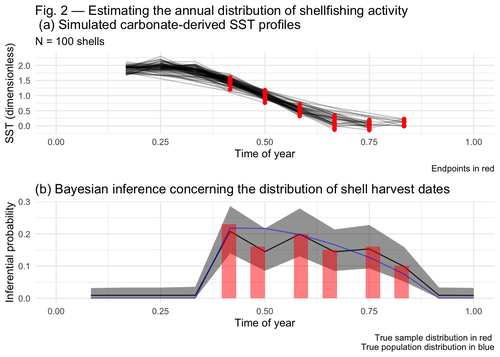

Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approachJordan Brown and Gabriel Lewis https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7949547Mixture models and seasonal mobilityRecommended by Alfredo Cortell-Nicolau and Simon Carrignon based on reviews by Iza Romanowska and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper by Brown & Lewis [1] presents an approach to measure seasonal mobility and subsistence practices. In order to do so, the paper proposes a Bayesian mixture model to estimate the annual distribution of shellfish harvesting activity. Following the recommendations of the two reviewers, the paper presents a clear and innovative method to assess seasonal mobility for prehistoric groups, although it could benefit from additional references regarding isotopic literature. While the adequacy of isotope analysis for estimating mobility patterns in Archaeology has been extensively proven by now, work on specific seasonal mobility is not that much abundant. However, this is a key issue, since seasonal mobility is one of the main social components defining the differences between groups both considering farming vs hunting and gathering or even among hunter-gatherer groups themselves. In this regard, the paper brings a valuable methodological resources that can be used for further research in this issue. One of its greatest values is the fact that it can quantify the uncertainty present in previous isotope studies in seasonal mobility. As stated by the authors, the model can still undergo several optimisation aspects, but as it stands, it is already providing a valuable asset regarding the quantification of uncertainy in the isotopic studies of seasonal mobility. Reference [1] Brown, J. and Lewis, G. (2024). Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approach. Zenodo, 7949547, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7949547 | Inferring shellfishing seasonality from the isotopic composition of biogenic carbonate: A Bayesian approach | Jordan Brown and Gabriel Lewis | <p>The problem of accurately and reliably estimating the annual distribution of seasonally-varying human settlement and subsistence practices is a classic concern among archaeologists, which has only become more relevant with the increasing import... |  | Archaeometry, Computational archaeology, Environmental archaeology, North America, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Alfredo Cortell-Nicolau | Iza Romanowska, Eduardo Herrera Malatesta, Alejandro Sierra Sainz-Aja, Sam Leggett, Christianne Fernee, Anonymous, Asier García-Escárzaga , Paul Szpak , Maria Elena Castiello , Jasmine Lundy , Tansy Branscombe | 2023-10-03 04:45:54 | View |

01 Dec 2022

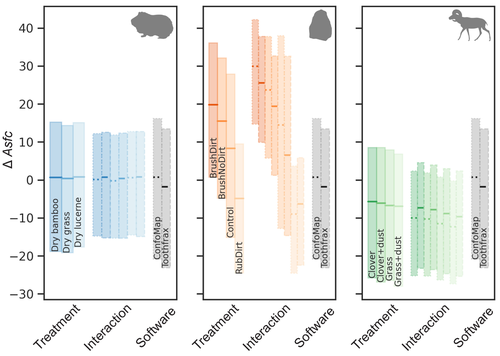

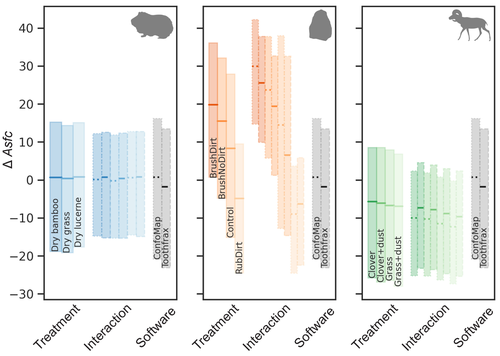

Surface texture analysis in Toothfrax and MountainsMap® SSFA module: Different software packages, different results?Ivan CALANDRA, Konstantin BOB, Gildas MERCERON, François BLATEYRON, Andreas HILDEBRANDT, Ellen SCHULZ-KORNAS, Antoine SOURON, Daniela E. WINKLER https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4671438An important comparison of software for Scale Sensitive Fractal Analysis : are ancient and new results compatible?Recommended by Alain Queffelec and Florent Rivals and Florent Rivals based on reviews by Antony Borel and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Antony Borel and 2 anonymous reviewers

The community of archaeologists, bioanthropologist and paleontologists relying on tools use-wear and dental microwear has grown in the recent years, mainly driven by the spread of confocal microscopes in the laboratories. If the diversity of microscopes is quite high, the main software used for 3D surface texture data analysis are mostly different versions of the same Mountains Map core. In addition to this software, since the beginning of 3D surface texture analysis in dental microwear, surface sensitive fractal analysis (SSFA) initially developed for industrial research (Brown & Savary, 1991) have been performed in our disciplines with the Sfrax/Toothfrax software for two decades (Ungar et al., 2003). This software being discontinued, these calculations have been integrated to the new versions of Mountains Map, with multi-core computing, full integration in the software and an update of the calculation itself. New research based on these standard parameters of surface texture analysis will be, from now on, mainly calculated with this new add-on of Mountains Map, and will be directly compared with the important literature based on the previous software. The question addressed by Calandra et al. (2022), gathering several prominent researchers in this domain including the Mountains Map developer F. Blateyron, is key for the future research: can we directly compare SSFA results from both software? Thanks to a Bayesian approach to this question, and comparing results calculated with both software on three different datasets (two on dental microwear, one on lithic raw materials), the authors show that the two software gives statistically different results for all surface texture parameters tested in the paper. Nevertheless, applying the new calculation to the datasets, they also show that the results published in original studies with these datasets would have been similar. Authors also claim that in the future, researchers will need to re-calculate the fractal parameters of previously published 3D surfaces and cannot simply integrate ancient and new data together. We also want to emphasize the openness of the work published here. All datasets have been published online and will be probably very useful for future methodological works. Authors also published their code for statistical comparison of datasets, and proposed a fully reproducible article that allowed the reviewers to check the content of the paper, which can also make this article of high interest for student training. This article is therefore a very important methodological work for the community, as noted by all three reviewers. It will certainly support the current transition between the two software packages and it is necessary that all surface texture specialists take these results and the recommendation of authors into account: calculate again data from ancient measurements, and share the 3D surface measurements on open access repositories to secure their access in the future. References Brown CA, and Savary G (1991) Describing ground surface texture using contact profilometry and fractal analysis. Wear, 141, 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(91)90269-Z Calandra I, Bob K, Merceron G, Blateyron F, Hildebrandt A, Schulz-Kornas E, Souron A, and Winkler DE (2022) Surface texture analysis in Toothfrax and MountainsMap® SSFA module: Different software packages, different results? Zenodo, 7219877, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7219877 Ungar PS, Brown CA, Bergstrom TS, and Walker A (2003) Quantification of dental microwear by tandem scanning confocal microscopy and scale-sensitive fractal analyses. Scanning: The Journal of Scanning Microscopies, 25, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/sca.4950250405 | Surface texture analysis in Toothfrax and MountainsMap® SSFA module: Different software packages, different results? | Ivan CALANDRA, Konstantin BOB, Gildas MERCERON, François BLATEYRON, Andreas HILDEBRANDT, Ellen SCHULZ-KORNAS, Antoine SOURON, Daniela E. WINKLER | <p>The scale-sensitive fractal analysis (SSFA) of dental microwear textures is traditionally performed using the software Toothfrax. SSFA has been recently integrated to the software MountainsMap® as an optional module. Meanwhile, Toothfrax suppor... |  | Computational archaeology, Palaeontology, Traceology | Alain Queffelec | Anonymous, John Charles Willman, Antony Borel | 2022-07-07 09:58:50 | View |

12 Feb 2024

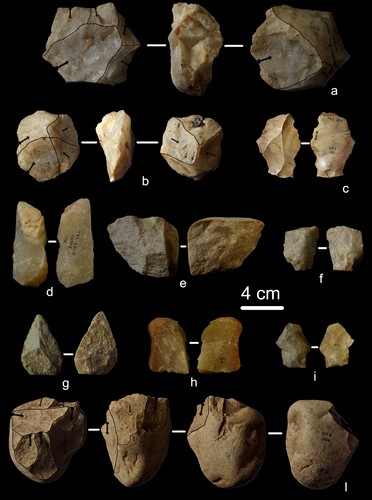

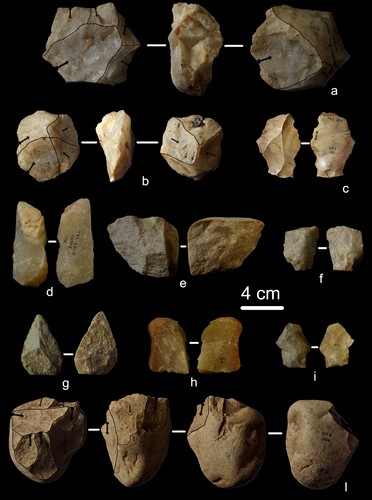

First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy)Sara Daffara, Carlo Giraudi, Gabriele L.F. Berruti, Sandro Caracausi, Francesca Garanzini https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4ufNot Simply the Surface: Manifesting Meaning in What Lies Above.Recommended by Marcel Kornfeld based on reviews by Lawrence Todd, Jason LaBelle and 2 anonymous reviewersThe archaeological record comes in many forms. Some, such as buried sites from volcanic eruptions or other abrupt sedimentary phenomena are perhaps the only ones that leave relatively clean snapshots of moments in the past. And even in those cases time is compressed. Much, if not all other archaeological record is a messy affair. Things, whatever those things may be, artifacts or construction works (i.e., features), moved, modified, destroyed, warped and in a myriad of ways modified from their behavioral contexts. Do we at some point say the record is worthless? Not worth the effort or continuing investigation. Perhaps sometimes this may be justified, but as Daffara and colleagues show, heavily impacted archaeological remains can give us clues and important information about the past. Thoughtful and careful prehistorians can make significant contributions from what appear to be poor archaeological records. In the case of Daffara and colleagues, a number of important theoretical cross-sections can be recognized. For a long time surface archaeology was thought of simply as a way of getting a preliminary peak at the subsurface. From some of the earliest professional archaeologists (e.g., Kidder 1924, 1931; Nelson 1916) to the New Archaeologists of the 1960s, the link between the surface and subsurface was only improved in precision and systematization (Binford et al. 1970). However, at Hatchery West Binford and colleagues not only showed that surface material can be used more reliably to get at the subsurface, but that substantive behavioral inferences can be made with the archaeological record visible on the surface. Much more important are the behavioral implications drawn from surface material. I am not sure we can cite the first attempts at interpreting prehistory from the surface manifestations of the archaeological record, but a flurry of such approaches proliferated in the 1970s and beyond (Dunnell and Dancey 1983; Ebert 1992; Foley 1981). Off-site archaeology, non-site archaeology, later morphing into landscape archaeology all deal strictly with surface archaeological record to aid in understanding the past. With the current paper, Daffara and colleagues (2024) are clearly in this camp. Although still not widely accepted, it is clear that some behaviors (parts of systems) can only be approached from surface archaeological record. It is very unlikely that a future archaeologist will be able to excavate an entire human social/cultural system; people moving from season to season, creating multiple long and short term camps, travelling, procuring resources, etc. To excavate an entire system one would need to excavate 20,000 km2 or some similarly impossible task. Even if it was physically possible to excavate such an enormous area, it is very likely that some of contextual elements of any such system will be surface manifestations. Without belaboring the point, surface archaeological record yields data like any other archaeological record. We must contextual the archaeological artifacts or features weather they come from surface or below. Daffara and colleagues show us that we can learn about deep prehistory of northern Italy, with collections that were unsystematically collected, biased by agricultural as well as other land deformations agents. They carefully describe the regional prehistory as we know it, in particular specific well documented sites and assemblages as a means of applying such knowledge to less well controlled or uncontrolled collections.

References Binford, L., Binford, R. S. R., Whallon, R. and Hardin, M. A. (1970). Archaeology of Hatchery West. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, No. 24, Washington D.C. Daffara, S., Giraudi, C., Berruti, G. L. F., Caracausi, S. and Garanzini, F. (2024). First evidence of a Palaeolithic frequentation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy), OSF Preprints, pz4uf, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pz4uf Dunnell, R. C. and Dancey, W. S. (1983). The siteless survey: a regional scale data collection strategy. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 6, edited by Michael B. Schiffer, pp. 267-287. Academic Press, New York. Ebert, J. I. (1992). Distributional Archaeology. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. Foley, R. A. (1981). Off site archaeology and human adaptation in eastern Africa: An analysis of regional artefact density in the Amboseli, Southern Kenya. British Archaeological Reports International Series 97. Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 3. Oxford England. Kidder, A. V. (1924). An Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology, With a Preliminary Account of the Excavations at Pecos. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy, no. 1. New Haven, Connecticut. Kidder, A. V. (1931). The Pottery of Pecos, vol. 1. Papers of the Southwestern Expedition, Phillips Academy. New Haven, Connecticut. Nelson, N. (1916). Chronology of the Tano Ruins, New Mexico. American Anthropologist 18(2):159-180. | First evidence of a Palaeolithic occupation of the Po plain in Piedmont: the case of Trino (north-western Italy) | Sara Daffara, Carlo Giraudi, Gabriele L.F. Berruti, Sandro Caracausi, Francesca Garanzini | <p>The Trino hill is an isolated relief located in north-western Italy, close to Trino municipality. The hill was subject of multidisciplinary studies during the 1970s, when, because of quarrying and agricultural activities, five concentrations of... |  | Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic | Marcel Kornfeld | 2023-10-04 16:58:19 | View | |

01 Dec 2021

A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-MaatheideSonja Tomasso, Dries Cnuts, Justin Coppe, Marijn Van Gils, Ferdi Geerts, Marc De Bie, Veerle Rots https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pf3smPotential of a large-scale functional analysis to reconstructing past human activities at the Final Palaeolithic site of Lommel-MaatheideRecommended by Marta Arzarello and Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti and Ana Abrunhosa and Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti and Ana Abrunhosa

The paper “A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide” [1] focuses on the final Palaeolithic (Federmesser) site of Lommel-Maatheide. Federmesser sites from northern Belgium such as Lommel-Maatheide, Meer and Rekem, show evidence for dense human occupation of specific areas located on top of Tardiglacial dunes nearby water bodies [2]. Preserved spatial distribution of finds at the sites suggest different activity areas and the presence of habitat structures [2]. However, because of the low organic preservation at the sites, functional analyses of lithic assemblages have the potential to significantly contribute to the spatial organisation of activities at these sites. This study by Tomasso et al. [1], represents an excellent example of a large-scale integrated approach to the study of lithic industries. The article undoubtedly demonstrates the potential of the proposed methodology and the reliability of the results obtained. The article explores two different aspects (linked and excellently interconnected here): the possibility to apply use wear, residue and fracture analyses, on lithic assemblages affected by taphonomical alterations and to study lithic assemblages from dune landscapes. The study allows to answer differentiated questions: what is the influence of taphonomical alterations on use wear analysis? How do excavation methods impact the formation of use wear and the preservation of residues? Can we recognize distinct domestic activities? The article also provides an interesting hypothesis about hunting activities and propulsion methods. The applied methodology is effectively interdisciplinary and innovative. It demonstrates how a truly integrated and articulated approach can represent the turning point for going beyond a mainly descriptive dimension to move towards a real understanding of the sites. Studies dedicated to the analysis of the propulsion mode are not very frequent, but they are surely very important to better understand human behaviour [3]. Here, the methodology developed for the evaluation of the propulsion mode represent an important starting point for the definition of a new approach. Morphological and morphometrical analysis are integrated to the evaluation of the mechanical stress, to fracture delineations and to the hafting system (the latter defined on experimental basis). This article therefore underlines the potential of combining different approaches to functional analysis associated with a ‘tailored’ reference collection and applying them to a high number of artefacts for reconstructing past human activities involving materials that are otherwise not preserved in these contexts. [1] Tomasso, S., Cnuts, D., Coppe, J., Geerts, F., Gils, M.V., Bie, M.D., Rots, V. (2021). A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pf3sm, ver 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. [2] De Bie, M., Van Gils, M. (2006). Les habitats des groupes à Federmesser (aziliens) dans le Nord de la Belgique. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 103, 781–790. [3] Coppe, J., Lepers, C., Clarenne, V., Delaunois, E., Pirlot, M. and Rots V. (2019). Ballistic Study Tackles Kinetic Energy Values of Palaeolithic Weaponry. Archaeometry, (61)4, 933-956. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12452 | A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide | Sonja Tomasso, Dries Cnuts, Justin Coppe, Marijn Van Gils, Ferdi Geerts, Marc De Bie, Veerle Rots | <p>The vast Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide, which is located in the Campine region (Northern Belgium), revealed the presence of numerous Final Palaeolithic concentrations situated on a large Late Glacial sand ridge on the northern edg... | Environmental archaeology, Landscape archaeology, Lithic technology, Traceology, Upper Palaeolithic | Marta Arzarello | 2021-09-14 17:04:38 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer