Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

20 Dec 2020

For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente.Marco Carpentieri, Marta Arzarello https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/2ptjbInvestigating the opportunistic debitage – an experimental approachRecommended by Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by David Hérisson and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper “For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente” [1] submitted by M. Carpentieri and M. Arzarello is a welcome addition to a growing number of studies focusing on flaking methods showing little to no core preparation, e.g., [2–4]. These flaking methods are often overlooked or seen as ‘simple’, which, in a Middle Palaeolithic context, sometimes leads to a dichotomy of Levallois vs. non-Levallois debitage (e.g., see discussion in [2]). The authors address this topic by first providing a definition for ‘opportunistic debitage’, derived from the definition of the ‘Alternating Surfaces Debitage System’ (SSDA, [5]). At the core of the definition is the adaptation to the characteristics (e.g., natural convexities and quality) of the raw material. This is one main challenge in studying this type of debitage in a consistent way, as the opportunistic debitage leads to a wide range of core and flake morphologies, which have sometimes been interpreted as resulting from different technical behaviours, but which the authors argue are part of a same ‘methodological substratum’ [1]. This article aims to further characterise the ‘opportunistic debitage’. The study relies on four archaeological assemblages from Italy, ranging from the Lower to the Upper Pleistocene, in which the opportunistic debitage has been recognised. Based on the characteristics associated with the occurrence of the opportunistic debitage in these assemblages, an experimental replication of the opportunistic debitage using the same raw materials found at these sites was conducted, with the aim to gain new insights into the method. Results show that experimental flakes and cores are comparable to the ones identified as resulting from the opportunistic debitage in the archaeological assemblage, and further highlight the high versatility of the opportunistic method. One outcome of the experimental replication is that a higher flake productivity is noted in the opportunistic centripetal debitage, along with the occurrence of 'predetermined-like' products (such as déjeté points). This brings the authors to formulate the hypothesis that the opportunistic debitage may have had a role in the process that will eventually lead to the development of Levallois and Discoid technologies. How this articulates with for example current discussions on the origins of Levallois technologies (e.g., [6–8]) is an interesting research avenue. This study also touches upon the question of how the implementation of one knapping method may be influenced by the broader technological knowledge of the knapper(s) (e.g., in a context where Levallois methods were common vs a context where they were not). It makes the case for a renewed attention in lithic studies for flaking methods usually considered as less behaviourally significant. [1] Carpentieri M, Arzarello M. 2020. For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente. OSF Preprints, doi:10.31219/osf.io/2ptjb [2] Bourguignon L, Delagnes A, Meignen L. 2005. Systèmes de production lithique, gestion des outillages et territoires au Paléolithique moyen : où se trouve la complexité ? Editions APDCA, Antibes, pp. 75–86. Available: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00447352 [3] Arzarello M, De Weyer L, Peretto C. 2016. The first European peopling and the Italian case: Peculiarities and “opportunism.” Quaternary International, 393: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.005 [4] Vaquero M, Romagnoli F. 2018. Searching for Lazy People: the Significance of Expedient Behavior in the Interpretation of Paleolithic Assemblages. J Archaeol Method Theory, 25: 334–367. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9339-x [5] Forestier H. 1993. Le Clactonien : mise en application d’une nouvelle méthode de débitage s’inscrivant dans la variabilité des systèmes de production lithique du Paléolithique ancien. Paléo, 5: 53–82. doi:10.3406/pal.1993.1104 [6] Moncel M-H, Ashton N, Arzarello M, Fontana F, Lamotte A, Scott B, et al. 2020. Early Levallois core technology between Marine Isotope Stage 12 and 9 in Western Europe. Journal of Human Evolution, 139: 102735. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102735 [7] White M, Ashton N, Scott B. 2010. The emergence, diversity and significance of the Mode 3 (prepared core) technologies. Elsevier. In: Ashton N, Lewis SG, Stringer CB, editors. The ancient human occupation of Britain. Elsevier. Amsterdam, pp. 53–66. [8] White M, Ashton N. 2003. Lower Palaeolithic Core Technology and the Origins of the Levallois Method in North‐Western Europe. Current Anthropology, 44: 598–609. doi:10.1086/377653 | For our world without sound. The opportunistic debitage in the Italian context: a methodological evaluation of the lithic assemblages of Pirro Nord, Cà Belvedere di Montepoggiolo, Ciota Ciara cave and Riparo Tagliente. | Marco Carpentieri, Marta Arzarello | <p>The opportunistic debitage, originally adapted from Forestier’s S.S.D.A. definition, is characterized by a strong adaptability to local raw material morphology and its physical characteristics and it is oriented towards flake production. Its mo... |  | Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Middle Palaeolithic | Alice Leplongeon | 2020-07-23 14:26:04 | View | |

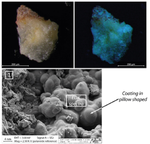

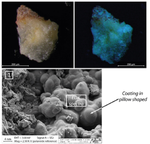

17 Jun 2022

Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France)Marine Quiers, Claire Chanteraud, Andréa Maris-Froelich, Émilie Chalmin-Aljanabi, Stéphane Jaillet, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Pairis, Yves Perrette, Hélène Salomon, Julien Monney https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03383193v5New method for the in situ detection and characterisation of amorphous silica in rock art contextsRecommended by Aitor Ruiz-Redondo based on reviews by Alain Queffelec, Laure Dayet and 1 anonymous reviewerSilica coating developed in cave art walls had an impact in the preservation of the paintings themselves. Despite it still exists a controversy about whether or not the effects contribute to the preservation of the artworks; it is evident that identifying these silica coatings would have an impact to assess the taphonomy of the walls and the paintings preserved on them. Unfortunately, current techniques -especially non-invasive ones- can hardly address amorphous silica characterisation. Thus, its presence is often detected on laboratory observations such as SEM or XRD analyses. In the paper “Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context - Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France)”, Quiers and collaborators propose a new method for the in situ detection and characterisation of amorphous silica in a rock art context based on UV laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) and UV illumination [1]. The results from both methods presented by the authors are convincing for the detection of U-silica mineralisation (U-opal in the specific case of study presented). This would allow access to a fast and cheap method to identify this kind of formations in situ in decorated caves. Beyond the relationship between opal coating and the preservation of the rock art, the detection of silica mineralisation can have further implications. First, it can help to define spot for sampling for pigment compositions, as well as reconstruct the chronology of the natural history of the caves and its relation with the human frequentation and activities. In conclusion, I am glad to recommend this original research, which offers a new approach to the identification of geological processes that affect -and can be linked with- the Palaeolithic cave art. [1] Quiers, M., Chanteraud, C., Maris-Froelich, A., Chalmin-Aljanabi, E., Jaillet, S., Noûs, C., Pairis, S., Perrette, Y., Salomon, H., Monney, J. (2022) Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France). HAL, hal-03383193, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03383193v5 | Light in the Cave: Opal coating detection by UV-light illumination and fluorescence in a rock art context. Methodological development and application in Points Cave (Gard, France) | Marine Quiers, Claire Chanteraud, Andréa Maris-Froelich, Émilie Chalmin-Aljanabi, Stéphane Jaillet, Camille Noûs, Sébastien Pairis, Yves Perrette, Hélène Salomon, Julien Monney | <p style="text-align: justify;">Silica coatings development on rock art walls in Points Cave questions the analytical access to pictorial matter specificities (geochemistry and petrography) and the rock art conservation state in the context of pig... |  | Archaeometry, Europe, Rock art, Taphonomy, Upper Palaeolithic | Aitor Ruiz-Redondo | 2021-10-25 11:12:48 | View | |

02 Sep 2023

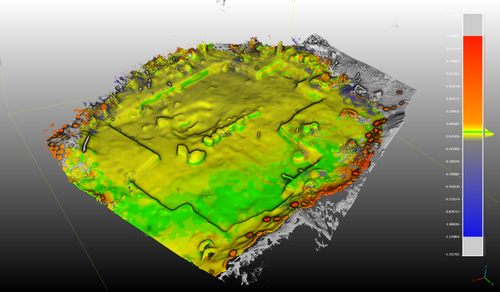

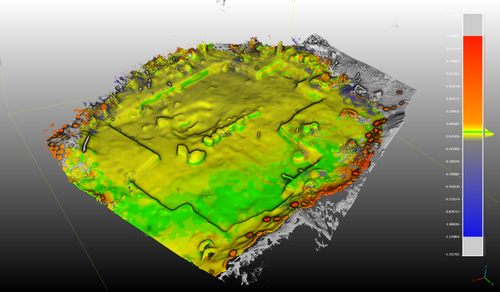

Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation ToolsNikolai Paukkonen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7954534The Potential of Mobile 3D Documentation using Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 ProRecommended by Ying Tung Fung based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and 1 anonymous reviewerI am pleased to recommend the paper titled "Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools" for consideration and publication as a preprint (Paukkonen, 2023). The paper addresses a timely and relevant topic within the field of archaeology and offers valuable insights into the evolving landscape of 3D documentation methods. The advances in technology over the past decade have brought about significant changes in archaeological documentation practices. This paper makes a valuable contribution by discussing the emergence of affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation. Given the constraints that many archaeologists face with limited resources and tight timeframes, the comparison between photogrammetry based on a video captured by a DJI Osmo Pocket gimbal camera and iPhone 12 Pro LiDAR scans is of great significance. The research presented in the paper showcases a practical application of these new technologies in the context of a Finnish Early Modern period archaeological project. By comparing the acquisition processes and evaluating the accuracy, precision, ease of use, and time constraints associated with each method, the authors provide a comprehensive assessment of their potential for archaeological fieldwork. This practical approach is a commendable aspect of the paper, as it not only explores the technical aspects but also considers the practical implications for archaeologists on the ground. Furthermore, the paper appropriately addresses the limitations of these technologies, specifically highlighting their potential inadequacy for projects requiring a higher level of precision, such as Neolithic period excavations. This nuanced perspective adds depth to the discussion and provides a realistic portrayal of the strengths and limitations of the new documentation methods. In conclusion, the paper offers valuable insights into the future of 3D field documentation for archaeologists. The authors' thorough evaluation and practical approach make this study a valuable resource for researchers, practitioners, and professionals in the field. I believe that this paper would be an excellent addition to PCIArchaeology and would contribute significantly to the ongoing dialogue within the archaeological community. References Paukkonen, N. (2023) Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools, Zenodo, 8281263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8281263 | Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools | Nikolai Paukkonen | <p>New affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation has appeared during the last years. Both photogrammetry and laser scanning are becoming affordable for archaeologists, who often work with limited resources and tight time constra... |  | Europe, Post-medieval, Remote sensing | Ying Tung Fung | 2023-05-21 21:32:33 | View | |

20 Jul 2022

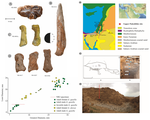

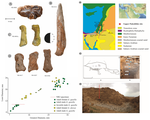

Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, IsraelNimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4New zooarchaeological data from the Upper Palaeolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2, IsraelRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio based on reviews by Ana Belén Galán and Joana Gabucio

The Levantine Corridor is considered a crossing point to Eurasia and one of the main areas for detecting population flows (and their associated cultural and economic changes) during the Pleistocene. This area could have been closed during the most arid periods, giving rise to processes of population isolation between Africa and Eurasia and intermittent contact between Eurasian human communities [1,2]. Zooarchaeological studies of the early Upper Palaeolithic assemblages constitute an important source of knowledge about human subsistence, making them central to the debate on modern behaviour. The Early Upper Palaeolithic sequence in the Levant includes two cultural entities – the Early Ahmarian and the Levantine Aurignacian. This latter is dated to 39-33 ka and is considered a local adaptation of the European Aurignacian techno-complex. In this work, the authors present a zooarchaeological study of the Nahal Rahaf 2 (ca. 35 ka) archaeological site in the southern Judean Desert in Israel [3]. Zooarchaeological data from the early Upper Paleolithic desert regions of the southern Levant are not common due to preservation problems of non-lithic finds. In the case of Nahal Rahaf 2, recent excavation seasons brought to light a stratigraphical sequence composed of very well-preserved archaeological surfaces attributed to the 'Arkov-Divshon' cultural entity, which is associated with the Levantine Aurignacian. This study shows age-specific caprine (Capra cf. Capra ibex) hunting on prime adults and a generalized procurement of gazelles (Gazella cf. Gazella gazella), which seem to have been selectively transported to the site and processed for within-bone nutrients. An interesting point to note is that the proportion of goats increases along the stratigraphic sequence, which suggests to the authors a specialization in the economy over time that is inversely related to the occupational intensity of use of the site. It is also noteworthy that the materials represent a large sample compared to previous studies from the Upper Paleolithic of the Judean Desert and Negev. In summary, this manuscript contributes significantly to the study of both the palaeoenvironment and human subsistence strategies in the Upper Palaeolithic and provides another important reference point for evaluating human hunting adaptations in the arid regions of the southern Levant. References [1] Bermúdez de Castro, J.-L., Martinon-Torres, M. (2013). A new model for the evolution of the human pleistocene populations of Europe. Quaternary Int. 295, 102-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.02.036 [2] Bar-Yosef, O., Belfer-Cohen, A. (2010). The Levantine Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic. In Garcea, E.A.A. (Ed), South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples Between 130,000 and 10,000 Years Ago. Oxbow Books, pp. 144-167. [3] Marom, N., Gnezdilov, D. L., Shafir, R., Barzilai, O. and Shemer, M. (2022). Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel. BioRxiv, 2022.05.17.492258, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.17.492258v4 | Faunal remains from the Upper Paleolithic site of Nahal Rahaf 2 in the southern Judean Desert, Israel | Nimrod Marom, Dariya Lokshin Gnezdilov, Roee Shafir, Omry Barzilai, Maayan Shemer | <p>Nahal Rahaf 2 (NR2) is an Early Upper Paleolithic (ca. 35 kya) rock shelter in the southern Judean Desert in Israel. Two excavation seasons in 2019 and 2020 revealed a stratigraphical sequence composed of intact archaeological surfaces attribut... |  | Upper Palaeolithic, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Joana Gabucio | 2022-05-19 06:16:47 | View |

02 Mar 2024

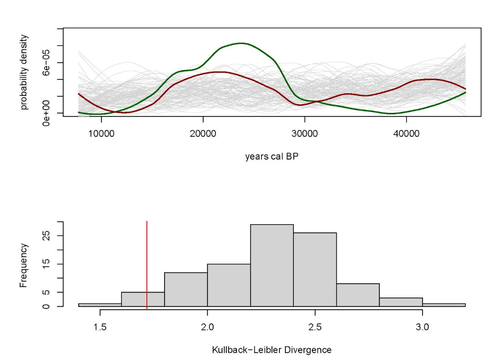

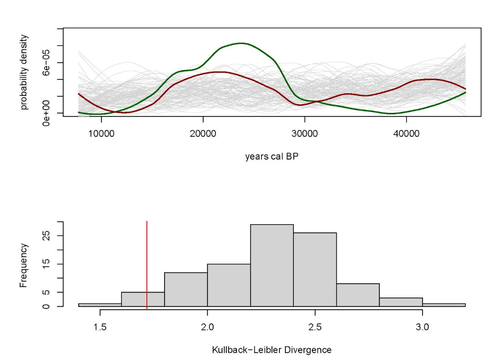

A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasetsNimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733A new approach to Predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer

Various biological systems have been subjected to mathematical modelling to enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions among different species. Among these models, the predator-prey model holds a significant position. Its relevance stems not only from its application in biology, where it largely governs the coexistence of diverse species in open ecosystems, but also from its utility in other domains. Predator-prey dynamics have long been a focal point in population ecology, yet access to real-world data is confined to relatively brief periods, typically less than a century. Studying predator-prey dynamics over extended periods presents challenges due to the limited availability of population data spanning more than a century. The most extensive dataset is the hare-lynx records from the Hudson Bay Company, documenting a century of fur trade [1]. However, other records are considerably shorter, usually spanning decades [2,3]. This constraint hampers our capacity to investigate predator-prey interactions over centennial or millennial scales. Marom and Wolkowski [4] propose here that leveraging regional radiocarbon databases offers a solution to this challenge, enabling the reconstruction of predator-prey population dynamics over extensive timeframes. To substantiate this proposition, they draw upon examples from Pleistocene Beringia and the Holocene Judean Desert. This approach is highly relevant and might provide insight into ecological processes occurring at a time scale beyond the limits of current ecological datasets. The methodological approach employed in this article proposes that the summed probability distribution (SPD) of predator radiocarbon dates, which reflects changes in population size, will demonstrate either more or less variation than anticipated from random sampling in a homogeneous distribution spanning the same timeframe. A deviation from randomness would imply a covariation between predator and prey populations. This basic hypothesis makes no assumptions about the frequency, mechanism, or cause of predator-prey interactions, as it is assumed that such aspects cannot be adequately tested with the available data. If validated, this hypothesis would offer initial support for the idea that long-term regional radiocarbon data contain signals of predator-prey interactions. This approach could justify the construction of larger datasets to facilitate a more comprehensive exploration of these signal structures.

References [1] Elton, C. and Nicholson, M., 1942. The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada. J. Anim. Ecol. 11, 215–244. [2] Gilg, O., Sittler, B. and Hanski, I., 2009. Climate change and cyclic predator-prey population dynamics in the high Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01927.x [3] Vucetich, J.A., Hebblewhite, M., Smith, D.W. and Peterson, R.O., 2011. Predicting prey population dynamics from kill rate, predation rate and predator-prey ratios in three wolf-ungulate systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01855.x [4] Marom, N. and Wolkowski, U. (2024). A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets, BioRxiv, 566733, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733 | A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets | Nimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski | <p>Predator-prey interactions have been a central theme in population ecology for the past century, but real-world data sets only exist for recent, relatively short (<100 years) time spans. This limits our ability to study centennial/millennial... |  | Bioarchaeology, Environmental archaeology, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | 2023-12-12 14:37:22 | View | |

15 Aug 2021

Ran-thok and Ling-chhom: indigenous grinding stones of Shertukpen tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, IndiaNorbu Jamchu Thongdok, Gibji Nimasow & Oyi Dai Nimasow https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5118675An insight into traditional method of food production in IndiaRecommended by Otis Crandell based on reviews by Antony Borel, Atefeh Shekofteh, Andrea Squitieri, Birgül Ögüt, Atefe Shekofte and 1 anonymous reviewerThis paper [1] covers an interesting topic in that it presents through ethnography an insight into a traditional method of food production which is gradually declining in use. In addition to preserving traditional knowledge, the ethnographic study of grinding stones has the potential for showing how similar tools may have been used by people in the past, particularly from the same geographic region. [1] Thongdok Norbu J., Nimasow Gibji, Nimasow Oyi D. (2021) Ran-thok and Ling-chhom: indigenous grinding stones of Shertukpen tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, India. Zenodo, 5118675, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeo. doi: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5118675 | Ran-thok and Ling-chhom: indigenous grinding stones of Shertukpen tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, India | Norbu Jamchu Thongdok, Gibji Nimasow & Oyi Dai Nimasow | <p style="text-align: justify;">The Shertukpens are an Indigenous tribal group inhabiting the western and southern parts of Arunachal Pradesh, Northeast India. They are accomplished carvers of carving wood and stone. The paper aims to document the... | Antiquity, Asia, Environmental archaeology, Lithic technology, Peopling, Raw materials | Otis Crandell | 2021-02-10 10:26:12 | View | ||

24 Jan 2024

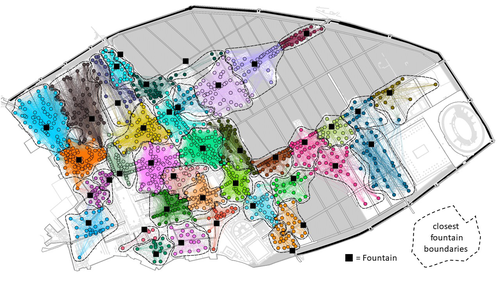

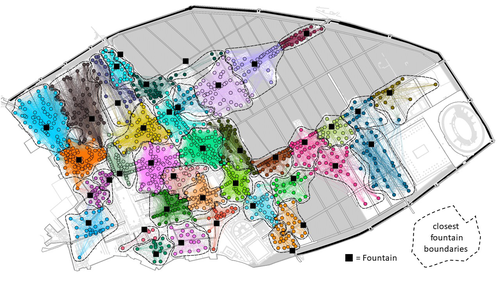

Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in PompeiiNotarian, Matthew https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305968A Valuable Contribution to Archaeological Network Research: A Case Study of PompeiiRecommended by David Laguna-Palma based on reviews by Matthew Peeples, Isaac Ullah and Philip Verhagen based on reviews by Matthew Peeples, Isaac Ullah and Philip Verhagen

The paper entitled 'Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii' [1] presents a significant contribution to the field of archaeological network research, particularly in the challenging task of identifying urban neighborhoods within the context of Pompeii. This study focuses on the relational dynamics within urban neighborhoods and examines their indistinct boundaries through advanced analytical methods. The methodology employed provides a comprehensive analysis of community detection, including the Louvain and Leiden algorithms, and introduces a novel Convex Hull of Admissible Modularity Partitions (CHAMP) algorithm. The incorporation of a network approach into this domain is both innovative and timely. The potential impact of this research is substantial, offering new perspectives and analytical tools. This opens new avenues for understanding social structures in ancient urban settings, which can be applied to other archaeological contexts beyond Pompeii. Moreover, the manuscript is not only methodologically solid but also well-written and structured, making complex concepts accessible to a broad audience. In conclusion, this study represents a valuable contribution to the field of archaeology, particularly for archaeological network research. Their results not only enhance our knowledge of Pompeii but also provide a robust framework for future studies in similar historical contexts. Therefore, this publication advances our understanding of social dynamics in historical urban environments. The rigorous analysis, combined with the innovative application of network algorithms, makes this study a noteworthy addition to the existing body of network science literature. It is recommended for a wide range of scholars interested in the intersection of archaeology, history, and network science. Reference [1] Notarian, Matthew. 2024. Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305968 | Social Network Analysis, Community Detection Algorithms, and Neighbourhood Identification in Pompeii | Notarian, Matthew | <p>The definition and identification of urban neighbourhoods in archaeological contexts remain complex and problematic, both theoretically and empirically. As constructs with both social and spatial characteristics, their detection through materia... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Computational archaeology, Mediterranean | David Laguna-Palma | 2023-08-31 19:28:35 | View | |

20 Mar 2024

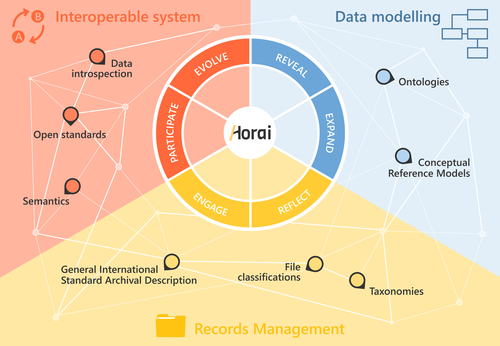

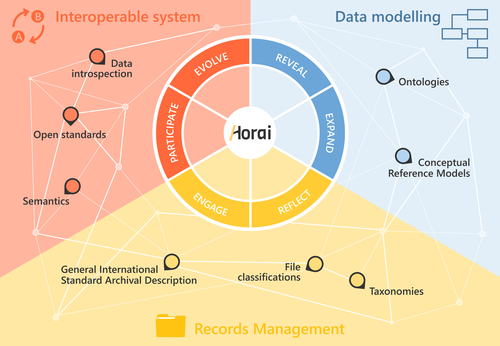

HORAI: An integrated management model for historical informationPablo del Fresno Bernal, Sonia Medina Gordo and Esther Travé Allepuz https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8185510A novel management model for historical informationRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Leandro Sánchez Zufiaurre and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper “HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information” presents a novel model for managing historical information. The study draws from an extensive indepth work in historical information management and a multi-disciplinary corpus of research ranging from heritage infrastructure research and practice to information studies and archival management literature. The paper ties into several key debates and discussions in the field showing awareness of the state-of-the-art of data management practice and theory. The authors argue for a new semantic data model HORAI and link it to a four-phase data management lifecycle model. The conceptual work is discussed in relation to three existing information systems partly predating and partly developed from the outset of the HORAI-model. While the paper shows appreciable understanding of the practical and theoretical state-of-the-art and the model has a lot of potential, in its current form it is still somewhat rough on the edges. Many of the both practical and theoretical threads introduced in the text warrant also more indepth consideration and it will be interesting to follow how the work will proceed in the future. For example, the comparison of the HORAI model and the ISAD(G): General International Standard Archival Description standard in the figure 1 is interesting but would require more elaboration. A slightly more thorough copyediting of the text would have also been helpful to make it more approachable. As a whole, in spite of the critique, I find both the paper and the model as valuable contributions to the literature and the practice of managing historical information. The paper reports thorough work, provides a lot of food for thought and several interesting lines of inquiry in the future. ReferencesDel Fresno Bernal, P., Medina Gordo, S. and Travé Allepuz, E. (2024). HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information. CAA 2023, Amsterdam, Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8185510 | HORAI: An integrated management model for historical information | Pablo del Fresno Bernal, Sonia Medina Gordo and Esther Travé Allepuz | <p>The archiving process goes beyond mere data storage, requiring a theoretical, methodological, and conceptual commitment to the sources of information. We present Horai as a semantic-based integration model designed to facilitate the development... |  | Computational archaeology, Spatial analysis | Isto Huvila | 2023-07-26 09:33:58 | View | |

27 Jun 2024

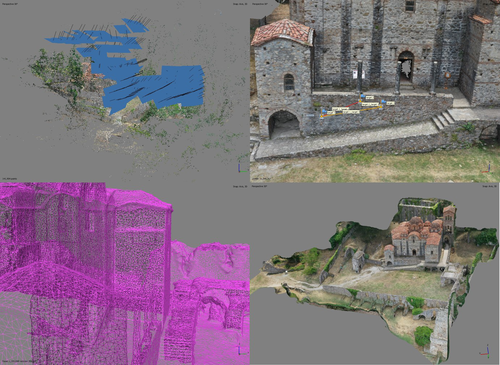

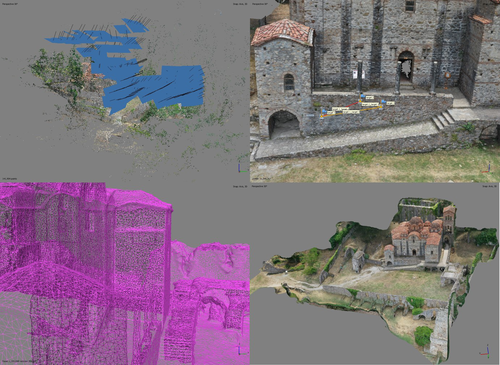

At the edge of the city: the digital storyline of the Bronchotion Monastery of MystrasPanagiotidis V. Vayia; Valantou Vasiliki; Kazolias Anastasios; Zacharias Nikolaos https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8126952Mystras Captured from the Air – Digital Recording Techniques for Cultural Heritage Management of a Monumental Archaeological SiteRecommended by Jitte Waagen based on reviews by Nikolai Paukkonen and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nikolai Paukkonen and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (Panagiotidis et al. 2024) discusses the digital approach to the ‘digital storyline’ of the Monastery of Brontochion of Mystras, Peloponnese, Greece. Using drone and terrestrial photogrammetric recording techniques, their goal is to produce maps and 3D models that will be integrated in the overall study of the medieval city, as well as function as a comprehensive visualisation of the archaeological site throughout its history. This will take shape as a web application using ArcGIS Online that will be a valuable platform presenting interactive visual information to accompany written publications. In addition, the assets in the database will be available for further advanced purposes, such as suggested by the authors; xR applications, educational games or digital smart guides. The authors of the paper do a good job in describing the historical background of the site and the purpose of the digital documentation techniques, and the applied methods and the technical details of the produced models are dealt with in detail. The paper presents a compelling case for an integrative approach to using digital recording techniques at an architectonically complex site for Cultural Heritage Management. It can be placed in a series of studies discussing how monumental sites can benefit from advanced digital recording techniques such as those presented in this paper (see for example Waagen and Wijngaarden 2024). The paper is recommended as an interesting read for all who are involved in this field. References Panagiotidis V. Vayia, Valantou Vasiliki, Kazolias Anastasios, and Zacharias Nikolaos. (2024). At the Edge of a City: The Digital Storyline of the Brontochion Monastery of Mystras. Zenodo, 8126952, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8126952 Waagen, J., and van Wijngaarden, G. J. (2024). Understanding Archaeological Site Topography: 3D Archaeology of Archaeology. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 7(1), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcaa.157 | At the edge of the city: the digital storyline of the Bronchotion Monastery of Mystras | Panagiotidis V. Vayia; Valantou Vasiliki; Kazolias Anastasios; Zacharias Nikolaos | <p>This study focuses on the digital depiction of the storyline of the Monastery of Brontochion of Mystras, located at the southwest edge of the city of Mystras, situated at the foot of Mt. Taygetos, six kilometres west of the city of Sparta in th... |  | Computational archaeology, Landscape archaeology, Mediterranean, Remote sensing, Spatial analysis | Jitte Waagen | 2023-10-03 17:02:54 | View | |

26 Mar 2024

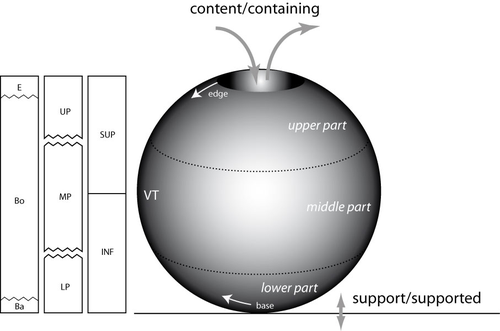

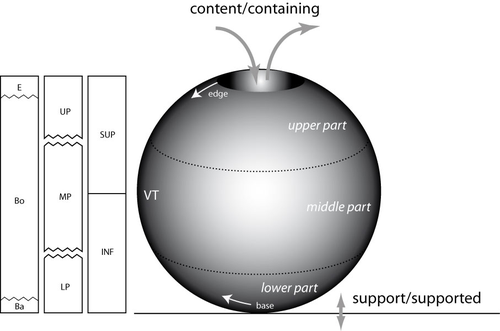

What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery.Philippe Boissinot https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433Abstract and Concrete – Querying the Metaphysics and Geometry of Pottery ClassificationRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

“What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery” by P. Boissinot (1) is a timely contribution to broader theoretical reflections on classification and ordering practices in archaeology, including type-construction and justification. Boissinot rightly reminds us that engagement with the type concept always touches upon the uneasy relationship between the abstract and the concrete, alternatively cast as the ongoing struggle in knowledge production between idealization and particularization. Types are always abstract and as such both ‘more’ and ‘less’ than the concrete objects they refer to. They are ‘more’ because they establish a higher-order identity of variously heterogeneous, concrete objects and they are ‘less’ because they necessarily reduce the richness of the concrete and often erase it altogether. The confusion that types evoke in archaeology and elsewhere has therefore a lot to do with the fact that types are simply not spatiotemporally distinct particulars. As abstract entities, types so almost automatically re-introduce the question of universalism but they do not decide this question, and Boissinot also tentatively rejects such ambitions. In fact, with Boissinot (1) it may be said that universality is often precisely confused with idealization, which is indispensable to all archaeological ordering practices. Idealization, increasingly recognized as an important epistemic operation in science (2, 3), paradoxically revolves around the deliberate misrepresentation of the empirical systems being studied, with models being the paradigm cases (4). Models can go so far as to assume something strictly false about the phenomena under consideration in order to advance their epistemic goals. In the words of Angela Potochnik (5), ‘the role of idealization in securing understanding distances understanding from truth but […] this understanding nonetheless gives rise to scientific knowledge’. The affinity especially to models may in part explain why types are so controversial and are often outright rejected as ‘real’ or ‘useful’ by those who only recognize the existence of concrete particulars (nominalism). As confederates of the abstract, types thus join the ranks of mathematics and geometry, which the author identifies as prototypical abstract systems. Definitions are also abstract. According to Boissinot (1), they delineate a ‘position of limits’, and the precision and rigorousness they bring comes at the cost of subjectivity. This unites definitions and types, as both can be precise and clear-cut but they can never be strictly singular or without alternative – in order to do so, they must rely on yet another higher-order system of external standards, and so ad infinitum. Boissinot (1) advocates a mathematical and thus by definition abstract approach to archaeological type-thinking in the realm of pottery, as the abstractness of this approach affords relatively rigorous description based on the rules of geometry. Importantly, this choice is not a mysterious a priori rooted in questionable ideas about the supposed superiority of such an approach but rather is the consequence of a careful theoretical exploration of the particularities (domain-specificities) of pottery as a category of human practice and materiality. The abstract thus meets the concrete again: objects of pottery, in sharp contrast to stone artefacts for example, are the product of additive processes. These processes, moreover, depend on the ‘fusion’ of plastic materials and the subsequent fixation of the resulting configuration through firing (processes which, strictly speaking, remove material, such as stretching, appear to be secondary vis-à-vis global shape properties). Because of this overriding ‘fusion’ of pottery, the identification of parts, functional or otherwise, is always problematic and indeterminate to some extent. As products of fusion, parts and wholes represent an integrated unity, and this distinguishes pottery from other technologies, especially machines. The consequence is that the presence or absence of parts and their measurements may not be a privileged locus of type-construction as they are in some biological contexts for example. The identity of pottery objects is then generally bound to their fusion. As a ‘plastic montage’ rather than an assembly of parts, individual parts cannot simply be replaced without threatening the identity of the whole. Although pottery can and must sometimes be repaired, this renders its objects broadly morpho-static (‘restricted plasticity’) rather than morpho-dynamic, which is a condition proper to other material objects such as lithic (use and reworking) and metal artefacts (deformation) but plays out in different ways there. This has a number of important implications, namely that general shape and form properties may be expected to hold much more relevant information than in technological contexts characterized by basal modularity or morpho-dynamics. It is no coincidence that ‘fusion’ is also emphasized by Stephen C. Pepper (6) as a key category of what he calls contextualism. Fusion for Pepper pays dividends to the interpenetration of different parts and relations, and points to a quality of wholes which cannot be reduced any further and integrates the details into a ‘more’. Pepper maintains that ‘fusion, in other words, is an agency of simplification and organization’ – it is the ‘ultimate cosmic determinator of a unit’ (p. 243-244, emphasis added). This provides metaphysical reasons to look at pottery from a whole-centric perspective and to foreground the agency of its materiality. This is precisely what Boissinot (1) does when he, inspired by the great techno-anthropologist François Sigaut (7), gestures towards the fact that elementarily a pot is ‘useful for containing’. He thereby draws attention not to the function of pottery objects but to what pottery as material objects do by means of their material agency: they disclose a purposive tension between content and container, the carrier and carried as well as inclusion and exclusion, which can also be understood as material ‘forces’ exerted upon whatever is to be contained. This, and not an emic reading of past pottery use, leads to basic qualitative distinctions between open and closed vessels following Anna O. Shepard’s (8) three basic pottery categories: unrestricted, restricted, and necked openings. These distinctions are not merely intuitive but attest to the object-specificity of pottery as fused matter. This fused dimension of pottery also leads to a recognition that shapes have geometric properties that emerge from the forced fusion of the plastic material worked, and Boissinot (1) suggests that curvature is the most prominent of such features, which can therefore be used to describe ‘pure’ pottery forms and compare abstract within-pottery differences. A careful mathematical theorization of curvature in the context of pottery technology, following George D. Birkhoff (9), in this way allows to formally distinguish four types of ‘geometric curves’ whose configuration may serve as a basis for archaeological object grouping. The idealization involved in this proposal is not accidental but deliberately instrumental – it reminds us that type-thinking in archaeology cannot escape the abstract. It is notable here that the author does not suggest to simply subject total pottery form to some sort of geometric-morphometric analysis but develops a proposal that foregrounds a limited range of whole-based geometric properties (in contrast to part-based) anchored in general considerations as to the material specificity of pottery as quasi-species of objects. As Boissinot (1) notes himself, this amounts to a ‘naturalization’ of archaeological artefacts and offers somewhat of an alternative (a third way) to the old discussion between disinterested form analysis and functional (and thus often theory-dependent) artefact groupings. He thereby effectively rejects both of these classic positions because the first ignores the particularities of pottery and the real function of artefacts is in most cases archaeologically inaccessible. In this way, some clear distance is established to both ethnoarchaeology and thing studies as a project. Attending to the ‘discipline of things’ proposal by Bjørnar Olsen and others (10, 11), and by drawing on his earlier work (12), Boissinot interestingly notes that archaeology – never dealing with ‘complete societies’ – could only be ‘deficient’. This has mainly to do with the underdetermination of object function by the archaeological record (and the confusion between function and functionality) as outlined by the author. It seems crucial in this context that Boissinot does not simply query ‘What is a thing?’ as other thing-theorists have previously done, but emphatically turns this question into ‘In what way is it not the same as something else?’. He here of course comes close to Olsen’s In Defense of Things insofar as the ‘mode of being’ or the ‘ontology’ of things is centred. What appears different, however, is the emphasis on plurality and within-thing heterogeneity on the level of abstract wholes. With Boissinot, we always have to speak of ontologies and modes of being and those are linked to different kinds of things and their material specificities. Theorizing and idealizing these specificities are considered central tasks and goals of archaeological classification and typology. As such, this position provides an interesting alternative to computational big-data (the-more-the-better) approaches to form and functionally grounded type-thinking, yet it clearly takes side in the debate between empirical and theoretical type-construction as essential object-specific properties in the sense of Boissinot (1) cannot be deduced in a purely data-driven fashion. Boissinot’s proposal to re-think archaeological types from the perspective of different species of archaeological objects and their abstract material specificities is thought-provoking and we cannot stop wondering what fruits such interrogations would bear in relation to other kinds of objects such as lithics, metal artefacts, glass, and so forth. In addition, such meta-groupings are inherently problematic themselves, and they thus re-introduce old challenges as to how to separate the relevant super-wholes, technological genesis being an often-invoked candidate discriminator. The latter may suggest that we cannot but ultimately circle back on the human context of archaeological objects, even if we, for both theoretical and epistemological reasons, wish to embark on strictly object-oriented archaeologies in order to emancipate ourselves from the ‘contamination’ of language and in-built assumptions.

Bibliography 1. Boissinot, P. (2024). What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery, Zenodo, 7429330, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433 2. Fletcher, S.C., Palacios, P., Ruetsche, L., Shech, E. (2019). Infinite idealizations in science: an introduction. Synthese 196, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02069-6 3. Potochnik, A. (2017). Idealization and the aims of science (University of Chicago Press). https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226507194.001.0001 4. J. Winkelmann, J. (2023). On Idealizations and Models in Science Education. Sci & Educ 32, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00291-2 5. Potochnik, A. (2020). Idealization and Many Aims. Philosophy of Science 87, 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1086/710622 6. Pepper S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (University of California Press). 7. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l’analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d’études Technologiques En Préhistoire. Bilan et Perspectives (Association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques), pp. 21–34. 8. Shepard, A. O. (1956). Ceramics for the Archeologist (Carnegie Institution of Washington n° 609). 9. Birkhoff G. D. (1933). Aesthetic Measure (Harvard University Press). 10. Olsen, B. (2010). In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects (AltaMira Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/ept014 11. Olsen, B., Shanks, M., Webmoor, T., Witmore, C. (2012). Archaeology: the discipline of things (University of California Press). https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520954007 12. Boissinot, P. (2011). “Comment sommes-nous déficients ?” in L’archéologie Comme Discipline ? (Le Seuil), pp. 265–308. | What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery. | Philippe Boissinot | <p>The main question we want to ask here concerns the application of philosophical considerations on identity about artifacts of a particular kind (pottery). The purpose is the recognition of types and their classification, which are two of the ma... |  | Ceramics, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2022-12-13 15:04:45 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer