Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▼ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

22 Apr 2024

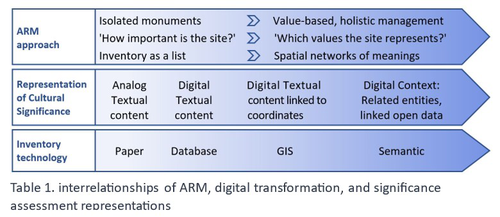

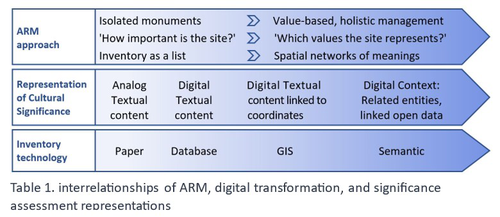

Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of MeaningsYael Alef, Yuval Shafriri https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309992How Semantic Technologies and Spatial Networks Can Enhance Archaeological Resource ManagementRecommended by James Stuart Taylor based on reviews by Dominik Lukas and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Dominik Lukas and 1 anonymous reviewer

After a thorough review and consideration of the revised manuscript titled "Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text to Spatial Networks of Meanings" by Yael Alef and Yuval Shafriri [1], I am recommending the paper for publication. The authors have made significant strides in addressing the feedback from the initial review process, notably enhancing the manuscript's clarity, methodological detail, and overall contribution to the field of Archaeological Resource Management (ARM). On balance I think the paper competently navigates the shift from a traditional significance-focused assessment of isolated archaeological sites to a more holistic and interconnected approach, leveraging graph data models and spatial networks. This transition represents an advancement in the field, offering deeper insights into the sociocultural dynamics of archaeological sites. The case study of ancient synagogues in northern Israel, particularly the Huqoq Synagogue, serves as a compelling illustration of the potential of semantic technologies to enrich our understanding of cultural heritage. Significantly, the authors have responded to the call for a clearer methodological framework by providing a more detailed exposition of their use of knowledge graph visualization and semantic technologies. This response not only strengthens the paper's scientific rigor but also enhances its accessibility and applicability to a broader audience within the conservation and heritage management community. However, I do think it remains important to acknowledge areas where further work could enrich the paper's contribution. While the manuscript makes notable advancements in the technical and methodological domains, the exploration of the ethical and political implications of semantic technologies in ARM remains less developed. Recognizing the complex interplay of ethical and political considerations in archaeological assessments is crucial for the responsible advancement of the field. Thus, I suggest that future work could productively focus on these dimensions, offering a more comprehensive view of the implications of integrating semantic technologies into heritage management practices. I don't think that this omission is a reason to withold the paper for publication or seek further review. In fact I think it stands alone a paper quite well. Perhaps the authors might consider this as a complementary line of inquiry in their future work in the field. In conclusion then, I believe the revised manuscript represents a valuable addition to the literature, pushing boundaries of how we assess, understand, and manage archaeological resources. Its focus on semantic technologies and the creation of spatial networks of meanings marks a significant step forward in the field. I believe its publication will stimulate further research and discussion, particularly in the realms of ethical and political considerations, which remain ripe for exploration. Therefore, I'm happy to endorse the publication of this manuscript. Reference [1] Alef, Y and Shafriri, Y. (2024). Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of Meanings. Zenodo, 8309992, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309992 | Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of Meanings | Yael Alef, Yuval Shafriri | <p>This study examines the shift towards a values-based approach for Archaeological Resource Management (ARM), emphasizing the integration of Context-Based Significance Assessment (CBSA) with semantic technologies into digital ARM inventories. We ... |  | Computational archaeology, Conservation/Museum studies, Spatial analysis | James Stuart Taylor | 2023-09-01 22:24:15 | View | |

08 Feb 2024

CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient CoinsUlrike Peter, Claus Franke, Jan Köster, Karsten Tolle, Sebastian Gampe, Vladimir F. Stolba https://zenodo.org/records/8263517The valuable Corpus Nummorum: a not so Little MinionRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Fleur Kemmers and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Fleur Kemmers and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper under review/recommendation deals with Corpus Nummorum (Peter et al. 2024). The Corpus Nummorum (CN) is web portal for ancient Greek coins from various collections (https://www.corpus-nummorum.eu/). The CN is a database and research tool for Greek coins dating between 600 BCE to 300 CE. While many traditional collection databases aim at collecting coins, CN also includes coin dies, coin types and issues. It aims at achieving a complete online coin type catalogue. The paper is not a paper in a traditional sense, but presents the CN as a tool and shows the functionalities in the system. The relevance and the possibilities of the CN for numismatists is made clear in the paper and the merits are clear even for me as a Roman archaeologist and non-numismatist. The CN was presented as a poster at the CAA 2023 in Amsterdam during “S03. Our Little Minions pt. V: small tools with major impact”, organized by Moritz Mennenga, Florian Thiery, Brigit Danthine and myself (Mennenga et al. 2023). Little Minions help us significantly in our daily work as small self-made scripts, home-grown small applications and small hardware devices. They often reduce our workload or optimize our workflows, but are generally under-represented during conferences and not often presented to the outside world. Therefore, the Little Minions form a platform that enables researchers and software engineers to share these tools (Thiery, Visser and Mennenga 2021). Little Minions have become a well known happening within the CAA-community since we started this in 2018, also because we do not only allow 10-minute lightning talks, but also spontaneous stand-up presentations during the conference. A full list of all minions presented in the past, can be found online: https://caa-minions.github.io/minions/. In a strict sense the CN would not count as a Little Minion, because it is a large project consisting of many minions that help a numismatist in his/her daily work. The CN seems a very Big Minion in that sense. Personally, I am very happy to see the database being developed as a fully open system and that code can be found on Github (https://github.com/telota/corpus-nummorum-editor), and also made citable with citation information in GitHub (see https://citation-file-format.github.io/) and a version deposited in Zenodo with DOI (Köster and Franke 2024). In addition, the authors claim that the CN will be shared based on the FAIR-principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016, 2019). These guidelines are developed to improve the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse of digital data. I feel that CN will be a way forward in open numismatics and open archaeology. The CN is well known within the numismatist community and it was hard to find reviewers in this close community, because many potential reviewers work together with one or more of the authors, or are involved in the project. This also proves the relevance of the CN to the research community and beyond. Luckily, a Roman numismatist and a specialist in digital/computational archaeology were able to provide valuable feedback on the current paper. The reviewers only submitted feedback on the first version of the paper (Peter et al. 2023). The numismatist was positive on the content and the usefulness of CN for the discipline in general. However, she pointed out some important points that need to be addressed. The digital specialist was positive is various aspects, but also raised some important issues in relation to technical aspects and the explanation thereof. While both were positive on the project and the paper in general, both reviewers pointed out some issues that were largely addressed in the second version of this paper. The revised version was edited throughout and the paper was strongly improved. The Corpus Nummorum is well presented in this easy to read paper, although the explanations can sometimes be slightly technical. This paper gives a good introduction to the CN and I recommend this for publication. I sincerely hope that the CN will contribute and keep on contributing to the domains of numismatics, (digital) archaeology and open science in general. References Köster, J and Franke, C. 2024 Corpus Nummorum Editor. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10458195 Mennenga, M, Visser, RM, Thiery, F and Danthine, B. 2023 S03. Our Little Minions pt. V: small tools with major impact. In:. Book of Abstracts. CAA 2023: 50 Years of Synergy. Amsterdam: Zenodo. pp. 249–251. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7930991 Peter, U, Franke, C, Köster, J, Tolle, K, Gampe, S and Stolba, VF. 2023 CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.8263518 Peter, U., Franke, C., Köster, J., Tolle, K., Gampe, S. and Stolba, V. F. (2024). CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins, Zenodo, 8263517, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8263517 Thiery, F, Visser, RM and Mennenga, M. 2021 Little Minions in Archaeology An open space for RSE software and small scripts in digital archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.4575167 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Aalbersberg, IjJ, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, ’t Hoen, PAC, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Velterop, J, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2016 The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1): 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 Wilkinson, MD, Dumontier, M, Jan Aalbersberg, I, Appleton, G, Axton, M, Baak, A, Blomberg, N, Boiten, J-W, da Silva Santos, LB, Bourne, PE, Bouwman, J, Brookes, AJ, Clark, T, Crosas, M, Dillo, I, Dumon, O, Edmunds, S, Evelo, CT, Finkers, R, Gonzalez-Beltran, A, Gray, AJG, Groth, P, Goble, C, Grethe, JS, Heringa, J, Hoen, PAC ’t, Hooft, R, Kuhn, T, Kok, R, Kok, J, Lusher, SJ, Martone, ME, Mons, A, Packer, AL, Persson, B, Rocca-Serra, P, Roos, M, van Schaik, R, Sansone, S-A, Schultes, E, Sengstag, T, Slater, T, Strawn, G, Swertz, MA, Thompson, M, van der Lei, J, van Mulligen, E, Jan Velterop, Waagmeester, A, Wittenburg, P, Wolstencroft, K, Zhao, J and Mons, B. 2019 Addendum: The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 6(1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0009-6 | CORPUS NUMMORUM – A Digital Research Infrastructure for Ancient Coins | Ulrike Peter, Claus Franke, Jan Köster, Karsten Tolle, Sebastian Gampe, Vladimir F. Stolba | <p>CORPUS NUMMORUM indexes ancient Greek coins from various landscapes and develops typologies. The coins and coin types are published on the multilingual website www.corpus-nummorum.eu utilizing numismatic authority data and adhering to FAIR prin... |  | Antiquity, Classic | Ronald Visser | 2023-08-18 17:37:51 | View | |

30 Sep 2022

Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF dataBharath Nair, Ismael Rodríguez Palomo, Bo Markussen, Carsten Wiuf, Sarah Fiddyment and Matthew Collins https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.13.483627Assessing glutamine deamination in ancient parchment samplesRecommended by Beatrice Demarchi based on reviews by Maria Codlin and 3 anonymous reviewersData authenticity and approaches to data authentication are crucial issues in ancient protein research. The advent of modern mass spectrometry has enabled the detection of traces of ancient biomolecules contained in fossils, including protein sequences. However, detecting proteins in ancient samples does not equate to demonstrating their endogenous nature: instead, if the mechanisms that drive protein preservation and degradation are understood, then the extent of protein diagenesis can be used for evaluating preservational quality, which in turn may be related to the authenticity of the protein data. The post-mortem deamidation of asparaginyl and glutamyl residues is a key degradation reaction, which can be assessed effectively on the basis of mass spectrometry data, and which has accrued a long history of research, both in terms of describing the mechanisms governing the reactions and with regard to the best strategies for assessing and quantifying the extent of glutamine (Gln) and asparagine (Asn) deamidation in ancient samples (Pal Chowdhury et al., 2019; Ramsøe et al., 2021, 2020; Schroeter and Cleland, 2016; Simpson et al., 2016; Solazzo et al., 2014; Welker et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2012). In their paper, Nair and colleagues (2022) build on this wealth of knowledge and present a tool for quantifying the extent of Gln deamidation in parchment. Parchment is a collagen-based material which can yield extraordinary insights into manuscript manufacturing practices in the past, as well as on the daily lives of the people who assembled and used them (“biocodicology”) (Fiddyment et al., 2021, 2019, 2015; Teasdale et al., 2017). Importantly, the extent of deamidation can be directly related to the quality of the parchment produced: rapid direct deamidation of Gln is induced by the liming process, therefore high extents of deamidation are linked to prolonged exposure to the high pH conditions which are typical of liming, thus implying lower-quality parchment. Nair et al.’s approach focuses on collagen peptides which are typically detected during MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analyses of parchment and build a simple three-step workflow able to yield an overall index of deamidation for a sample (the parchment glutamine index - PQI) 一 taking into account that different Gln residues degrade at different rates according to their micro-chemical environment. The first step involves pre-processing the MALDI spectra, since Nair et al. are specifically interested in maximising information which can be obtained by low-quality data. The second step builds on well-established methods for quantifying Q → E from MALDI-TOF data by modelling the convoluted isotope distributions (Wilson et al., 2012). Once relative rates of deamidation in selected peptides within a given sample are calculated, the third step uses a mixed effects model to combine the individual deamidation estimates and to obtain an overall estimate of the deamidation for a parchment sample (PQI). The PQI can be used effectively for assessing parchment quality, as the authors show for the dataset from Orval Abbey. However, PQI could also have wider applications to the study of processed collagen, which is widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries. In general, the study by Nair et al. is a welcome addition to a growing body of research on protein diagenesis, which will ultimately improve models for the assessment of the authenticity of biomolecular data in archaeology. References Chowdhury, P.M., Wogelius, R., Manning, P.L., Metz, L., Slimak, L., and Buckley, M. 2019. Collagen deamidation in archaeological bone as an assessment for relative decay rates. Archaeometry 61:1382–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12492 Fiddyment, S., Goodison, N.J., Brenner, E., Signorello, S., Price, K., and Collins, M.J.. 2021. Girding the loins? Direct evidence of the use of a medieval parchment birthing girdle from biomolecular analysis. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.202055 Fiddyment,S., Holsinger, B., Ruzzier, C., Devine, A., Binois, A., Albarella, U., Fischer, R., Nichols, E., Curtis, A., Cheese, E., Teasdale, M.D., Checkley-Scott, C., Milner, S.J., Rudy, K.M., Johnson, E.J., Vnouček, J., Garrison, M., McGrory, S., Bradley, D.G., and Collins, M.J. 2015. Animal origin of 13th-century uterine vellum revealed using noninvasive peptide fingerprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:15066–15071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1512264112 Fiddyment, S., Teasdale, M.D., Vnouček, J., Lévêque, É., Binois, A., and Collins, M.J. 2019. So you want to do biocodicology? A field guide to the biological analysis of parchment. Heritage Science 7:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0278-6 Nair, B., Rodríguez Palomo, I., Markussen, B., Wiuf, C., Fiddyment, S., and Collins, M. Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF data. BiorRxiv, 2022.03.13.483627, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.13.483627 Ramsøe, A., Crispin, M., Mackie, M., McGrath, K., Fischer, R., Demarchi, B., Collins, M.J., Hendy, J., and Speller, C. 2021. Assessing the degradation of ancient milk proteins through site-specific deamidation patterns. Sci Rep 11:7795. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87125-x Ramsøe, A., van Heekeren, V., Ponce, P., Fischer, R., Barnes, I., Speller, C., and Collins, M.J. 2020. DeamiDATE 1.0: Site-specific deamidation as a tool to assess authenticity of members of ancient proteomes. J Archaeol Sci 115:105080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2020.105080 Schroeter, E.R., and Cleland, T.P. 2016. Glutamine deamidation: an indicator of antiquity, or preservational quality? Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 30:251–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7445 Simpson, J.P., Penkman, K.E.H., and Demarchi, B. 2016. The effects of demineralisation and sampling point variability on the measurement of glutamine deamidation in type I collagen extracted from bone. J Archaeol Sci 69: 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.002 Solazzo, C., Wilson, J., Dyer, J.M., Clerens, S., Plowman, J.E., von Holstein, I., Walton Rogers, P., Peacock, E.E., and Collins, M.J. 2014. Modeling deamidation in sheep α-keratin peptides and application to archeological wool textiles. Anal Chem 86:567–575. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac4026362 Teasdale, M.D., Fiddyment, S., Vnouček, J., Mattiangeli, V., Speller, C., Binois, A., Carver, M., Dand, C., Newfield, T.P., Webb, C.C., Bradley, D.G., and Collins M.J. 2017. The York Gospels: a 1000-year biological palimpsest. R Soc Open Sci 4:170988. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.170988 Welker, F., Soressi, M.A., Roussel, M., van Riemsdijk, I., Hublin, J.-J., and Collins, M.J. 2016. Variations in glutamine deamidation for a Châtelperronian bone assemblage as measured by peptide mass fingerprinting of collagen. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 3:15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2016.1258825 Wilson, J., van Doorn, N.L., and Collins, M.J. 2012. Assessing the extent of bone degradation using glutamine deamidation in collagen. Anal Chem 84:9041–9048. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac301333t | Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF data | Bharath Nair, Ismael Rodríguez Palomo, Bo Markussen, Carsten Wiuf, Sarah Fiddyment and Matthew Collins | <p style="text-align: justify;">Parchment was used as a writing material in the Middle Ages and was made using animal skins by liming them with Ca(OH)<span class="math-tex">\( _2 \)</span>. During liming, collagen peptides containing Glutamine (Q)... | Bioarchaeology, Europe, Medieval, Zooarchaeology | Beatrice Demarchi | 2022-03-22 12:54:10 | View | ||

13 Jan 2024

Dealing with post-excavation data: the Omeka S TiMMA web-databaseBastien Rueff https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7989904Managing Archaeological Data with Omeka SRecommended by Jonathan Hanna based on reviews by Electra Tsaknaki and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Electra Tsaknaki and 1 anonymous reviewer

Managing data in archaeology is a perennial problem. As the adage goes, every day in the field equates to several days in the lab (and beyond). For better or worse, past archaeologists did all their organizing and synthesis manually, by hand, but since the 1970s ways of digitizing data for long term management and analysis have gained increasing attention [1]. It is debatable whether this ever actually made things easier, particularly given the associated problem of sustainable maintenance and accessibility of the data. Many older archaeologists, for instance, still have reels and tapes full of data that now require a new form of archaeology to excavate (see [2] for an unrealized idea on how to solve this). Today, the options for managing digital archaeological data are limited only by one’s imagination. There are systems built specifically for archaeology, such as Arches [3], Ark [4], Codifi [5], Heurist [6], InTerris Registries [7], OpenAtlas [8], S-Archeo [9], and Wild Note [10], as well as those geared towards museum collections like PastPerfect [11] and CatalogIt [12], among others. There are also mainstream databases that can be adapted to archaeological needs like MS Access [13] and Claris FileMaker [14], as well as various web database apps that function in much the same way (e.g., Caspio [15], dbBee [16], Amazon's Simpledb [17], Sci-Note [18], etc.) — all with their own limitations in size, price, and utility. One could also write the code for specific database needs using pre-built frameworks like those in Ruby-On-Rails [19] or similar languages. And of course, recent advances in machine-learning and AI will undoubtedly bring new solutions in the near future. But let’s be honest — most archaeologists probably just use Excel. That's partly because, given all the options, it is hard to decide the best tool and whether its worth changing from your current system, especially given few real-world examples in the literature. Bastien Rueff’s new paper [20] is therefore a welcomed presentation on the use of Omeka S [21] to manage data collected for the Timbers in Minoan and Mycenaean Architecture (TiMMA) project. Omeka S is an open-source web-database that is based in PHP and MySQL, and although it was built with the goal of connecting digital cultural heritage collections with other resources online, it has been rarely used in archaeology. Part of the issue is that Omeka Classic was built for use on individual sites, but this has now been scaled-up in Omeka S to accommodate a plurality of sites. Some of the strengths of Omeka S include its open-source availability (accessible regardless of budget), the way it links data stored elsewhere on the web (keeping the database itself lean), its ability to import data from common file types, and its multi-lingual support. The latter feature was particularly important to the TiMAA project because it allowed members of the team (ranging from English, Greek, French, and Italian, among others) to enter data into the system in whatever language they felt most comfortable. However, there are several limitations specific to Omeka S that will limit widespread adoption. Among these, Omeka S apparently lacks the ability to export metadata, auto-fill forms, produce summations or reports, or provide basic statistical analysis. Its internal search capabilities also appear extremely limited. And that is not to mention the barriers typical of any new software, such as onerous technical training, questionable long-term sustainability, or the need for the initial digitization and formatting of data. But given the rather restricted use-case for Omeka S, it appears that this is not a comprehensive tool but one merely for data entry and storage that requires complementary software to carry out common tasks. As such, Rueff has provided a review of a program that most archaeologists will likely not want or need. But if one was considering adopting Omeka S for a project, then this paper offers critical information for how to go about that. It is a thorough overview of the software package and offers an excellent example of its use in archaeological practice.

[1] Doran, J. E., and F. R. Hodson (1975) Mathematics and Computers in Archaeology. Harvard University Press. [2] Snow, Dean R., Mark Gahegan, C. Lee Giles, Kenneth G. Hirth, George R. Milner, Prasenjit Mitra, and James Z. Wang (2006) Cybertools and Archaeology. Science 311(5763):958–959. [3] https://www.archesproject.org/ [4] https://ark.lparchaeology.com/ [5] https://codifi.com/ [6] https://heuristnetwork.org/ [7] https://www.interrisreg.org/ [8] https://openatlas.eu/ [9] https://www.skinsoft-lab.com/software/archaelogy-collection-management [10] https://wildnoteapp.com/ [11] https://museumsoftware.com/ [12] https://www.catalogit.app/ [13] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/access [14] https://www.claris.com/filemaker/ [15] https://www.caspio.com/ [16] https://www.dbbee.com/ [17] https://aws.amazon.com/simpledb/ [18] https://www.scinote.net/ [19] https://rubyonrails.org/ [20] Rueff, Bastien (2023) Dealing with Post-Excavation Data: The Omeka S TiMMA Web-Database. peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://zenodo.org/records/7989905 [21] https://omeka.org/

| Dealing with post-excavation data: the Omeka S TiMMA web-database | Bastien Rueff | <p>This paper reports on the creation and use of a web database designed as part of the TiMMA project with the Content Management System Omeka S. Rather than resulting in a technical manual, its goal is to analyze the relevance of using Omeka S in... |  | Buildings archaeology, Computational archaeology | Jonathan Hanna | 2023-05-31 12:16:25 | View | |

08 Apr 2024

Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contextsAline Deicke https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8310170A new approach to a data ontology for the qualitative assessment of funerary spacesRecommended by Asuman Lätzer-Lasar based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

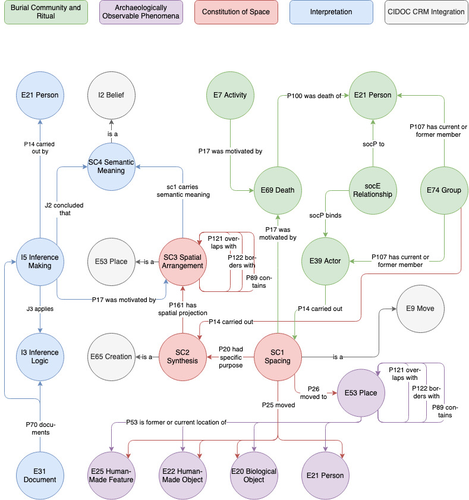

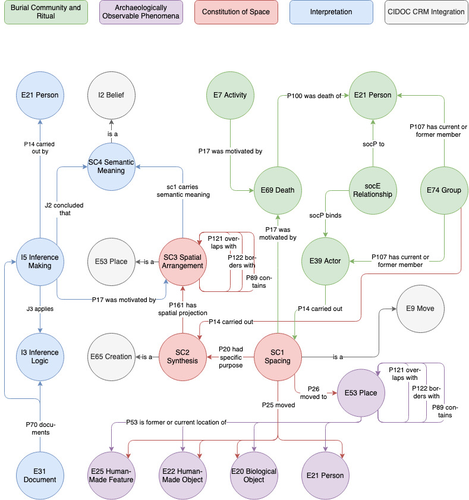

The paper by Aline Deicke [1] is very readable, and it succeeds in presenting a still unnoticed topic in a well-structured way. It addresses the topic of “how to model social-spatial relations in antiquity”, as the title concisely implies, and makes important and interesting points about their interrelationship by drawing on latest theories of sociologists such as Martina Löw combined with digital tools, such as the CIDOC CRM-modeling. The author provides an introductory insight into the research history of funerary archaeology and addresses the problematic issue of not having investigated fully the placement of entities of the grave inventory. So far, the focus of the analysis has been on the composition of the assemblage and not on the positioning within this space-and time-limited context. However, the positioning of the various entities within the burial context also reveals information about the objects themselves, their value and function, as well as about the world view and intentions of the living and dead people involved in the burial. To obtain this form of qualitative data, the author suggests modeling knowledge networks using the CIDOC CRM. The method allows to integrate the spatial turn combined with aspects of the actor-network-theory. The theoretical backbone of the contribution is the fundamental scholarship of Martina Löw’s “Raumsoziologie” (sociology of space), especially two categories of action namely placing and spacing (SC1). The distinction between the two types of action enables an interpretative process that aims for the detection of meaningfulness behind the creation process (deposition process) and the establishment of spatial arrangement (find context). To illustrate with a case study, the author discusses elite burial sites from the Late Urnfield Period covering a region north of the Alps that stretches from the East of France to the entrance of the Carpathian Basin. With the integration of very basic spatial relations, such as “next to”, “above”, “under” and qualitative differentiations, for instance between iron and bronze knives, the author detects specific patterns of relations: bronze knives for food preparing (ritual activities at the burial site), iron knives associated with the body (personal accoutrement). The complexity of the knowledge engineering requires the gathering of several CIDOC CRM extensions, such as CRMgeo, CRMarchaeo, CRMba, CRMinf and finally CRMsoc, the author rightfully suggests. In the end, the author outlines a path that can be used to create this kind of data model as the basis for a graph database, which then enables a further analysis of relationships between the entities in a next step. Since this is only a preliminary outlook, no corrections or alterations are needed. The article is an important step in advancing digital archaeology for qualitative research. References [1] Deicke, A. (2024). Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contexts. Zenodo, 8310170, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8310170 | Spaces of funeral meaning. Modelling socio-spatial relations in burial contexts | Aline Deicke | <p>Burials have long been one of the most important sources of archaeology, especially when studying past social practices and structure. Unlike archaeological finds from settlements, objects from graves can be assumed to have been placed there fo... |  | Computational archaeology, Protohistory, Spatial analysis, Theoretical archaeology | Asuman Lätzer-Lasar | 2023-09-01 23:15:41 | View | |

21 Mar 2023

Automation and Novelty –Archaeocomputational Typo-Praxis in the Wake of the Third Science RevolutionRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Rachel Crellin and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Rachel Crellin and 1 anonymous reviewer

“Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology” submitted by G. Lucas (1) offers a refreshing and welcome reflection on the role of computer-based practice, type-thinking and approaches to typology in the age of big data and the widely proclaimed ‘Third Science Revolution’ (2–4). At the annual meeting of the EAA in Maastricht in 2017, a special thematic block was dedicated to issues and opportunities linked to the Third Science Revolution in archaeology “because of [its] profound and wide ranging impact on practice and theory in archaeology for the years to come” (5). Even though the Third Science Revolution, as influentially outlined by Kristiansen in 2014 (2), has occasionally also been met with skepticism and critique as to its often implicit scientism and epistemological naivety (6–8), archaeology as a whole seems largely euphoric as to the promises of the advancing ‘revolution’. As Lucas perceptively points out, some even regard it as the long-awaited opportunity to finally fulfil the ambitions and goals of Anglophone processualism. The irony here, as Lucas rightly notes, is that early processualists initially foregrounded issues of theory and scientific epistemology, while much work conducted under the banner of the Third Science Revolution, especially within its computational branches, does not. Big data advocates have echoed Anderson’s much-cited “end of theory” (9) or at least emphatically called for an ‘empirization’ and ‘computationalization’ of theory, often under the banner of ‘data-driven archaeology’ (10), yet typically without much specification of what this is supposed to mean for archaeological theory and reflexivity. The latter is indeed often openly opposed by archaeological Third Science Revolution enthusiasts, arguably because it is viewed as part of the supposedly misguided ‘post-modernist’ project. Lucas makes an original meta-archaeological contribution here and attempts to center the epistemological, ontological and praxeological dimensions of what is actually – in situated archaeological praxis and knowledge-production – put at stake by the mobilization of computers, algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI), including its many but presently under-reflected implications for ordering practices such as typologization. Importantly, his perspective thereby explicitly and deliberately breaks with the ‘normative project’ in traditional philosophy of science, which sought to nail down a universal, prescriptive way of doing science and securing scientific knowledge. He instead focuses on the practical dimensions and consequences of computer-reliant archaeologies, what actually happens on the ground as researchers try to grapple with the digital and the artefactual and try to negotiate new insights and knowledge, including all of the involved messiness – thereby taking up the powerful impetus of the broader practice turn in interdisciplinary science studies and STS (Science and Technology Studies (11)) (12–14), which have recently also re-oriented archaeological self-observation, metatheory and epistemology (15). This perspective on the dawning big data age in archaeology and incurred changes in the status, nature and aims of type-thinking produces a number of important insights, which Lucas fruitfully discusses in relation to promises of ‘automation’ and ‘novelty’ as these feature centrally in the rhetorics and politics of the Third Science Revolution. With regard to automation, Lucas makes the important point that machine or computer work as championed by big data proponents cannot adequately be qualified or understood if we approach the issue from a purely time-saving perspective. The question we have to ask instead is what work do machines actually do and how do they change the dynamics of archaeological knowledge production in the process? In this optic, automation and acceleration achieved through computation appear to make most sense in the realm of the uncontroversial, in terms of “reproducing an accepted way of doing things” as Lucas says, and this is precisely what can be observed in archaeological practice as well. The ramifications of this at first sight innocent realization are far-reaching, however. If we accept the noncontroversial claim that automation partially bypasses the need for specialists through the reproduction of already “pre-determined outputs”, automated typologization would primarily be useful in dealing with and synthesizing larger amounts of information by sorting artefacts into already accepted types rather than create novel types or typologies. If we identity the big data promise at least in part with automation, even the detection of novel patterns in any archaeological dataset used to construct new types cannot escape the fact that this novelty is always already prefigured in the data structure devised. The success of ‘supervised learning’ in AI-based approaches illustrates this. Automation thus simply shifts the epistemological burden back to data selection and preparation but this is rarely realized, precisely because of the tacit requirement of broad non-contentiousness. Minimally, therefore, big data approaches ironically curtail their potential for novelty by adhering to conventional data treatment and input formats, rarely problematizing the issue of data construction and the contested status of (observational) data themselves. By contrast, they seek to shield themselves against such attempts and tend to retain a tacit universalism as to the nature of archaeological data. Only in this way is it possible to claim that such data have the capacity to “speak for themselves”. To use a concept borrowed from complexity theory, archaeological automation-based type-construction that relies on supposedly basal, incontrovertible data inputs can only ever hope to achieve ‘weak emergence’ (16) – ‘strong emergence’ and therefore true, radical novelty require substantial re-thinking of archaeological data and how to construct them. This is not merely a technical question as sometimes argued by computational archaeologies – for example with reference to specifically developed, automated object tracing procedures – as even such procedures cannot escape the fundamental question of typology: which kind of observations to draw on in order to explore what aspects of artefactual variability (and why). The focus on readily measurable features – classically dimensions of artefactual form – principally evades the key problem of typology and ironically also reduces the complexity of artefactual realities these approaches assert to take seriously. The rise of computational approaches to typology therefore reintroduces the problem of universalism and, as it currently stands, reduces the complexity of observational data potentially relevant for type-construction in order to enable to exploration of the complexity of pattern. It has often been noted that this larger configuration promotes ‘data fetishism’ and because of this alienates practitioners from the archaeological record itself – to speak with Marxist theory that Lucas briefly touches upon. We will briefly return to the notion of ‘distance’ below because it can be described as a symptomatic research-logical trope (and even a goal) in this context of inquiry. In total, then, the aspiration for novelty is ultimately difficult to uphold if computational archaeologies refuse to engage in fundamental epistemological and reflexive self-engagement. As Lucas poignantly observes, the most promising locus for novelty is currently probably not to be found in the capacity of the machines or algorithms themselves, but in the modes of collaboration that become possible with archaeological practitioners and specialists (and possibly diverse other groups of knowledge stakeholders). In other words, computers, supercomputers and AI technologies do not revolutionize our knowledge because of their superior computational and pattern-detection capacities – or because of some mysterious ‘superintelligence’ – but because of the specific ‘division of labour’ they afford and the cognitive challenge(s) they pose. Working with computers and AI also often requires to ask new questions or at least to adapt the questions we ask. This can already be seen on the ground, when we pay attention to how machine epistemologies are effectively harnessed in archaeological practice (and is somewhat ironic given that the promise of computational archaeology is often identified with its potential to finally resolve "long-standing (old) questions"). The Third Science Revolution likely prompts a consequential transformation in the structural and material conditions of the kinds of ‘distributed’ processes of knowledge production that STS have documented as characteristic for scientific discoveries and knowledge negotiations more generally (14, 17, 18). This ongoing transformation is thus expected not only to promote new specializations with regard to the utilization of the respective computing infrastructures emerging within big data ecologies but equally to provoke increasing demand for new ways of conceptualizing observations and to reformulate the theoretical needs and goals of typology in archaeology. The rediscovery of reflexivity as an epistemic virtue within big data debates would be an important step into this direction, as it would support the shared goal of achieving true epistemic novelty, which, as Lucas points out, is usually not more than an elusive self-declaration. Big data infrastructures require novel modes of human-machine synergy, which simply cannot be developed or cultivated in an atheoretical and/or epistemological disinterested space. Lucas’ exploration ultimately prompts us to ask big questions (again), and this is why this is an important contribution. The elephant in the room, of course, is the overly strong notion of objectivity on which much computational archaeology is arguably premised – linked to the vow to eventually construct ‘objective typologies’. This proclivity, however, re-tables all the problematic debates of the 1960s and – to speak with the powerful root metaphor of the machine fueling much of causal-mechanistic science (19, 20) – is bound to what A. Wylie (21) and others have called the ‘view from nowhere’. Objectivity, in this latter view, is defined by the absence of positionality and subjectivity – chiefly human subjectivity – and the promise of the machine, and by extension of computational archaeology, is to purify and thus to enhance processes of knowledge production by minimizing human interference as much as possible. The distancing of the human from actual processes of data processing and inference is viewed as positive and sometimes even as an explicit goal of scientific development. Interestingly, alienation from the archaeological record is framed as an epistemic virtue here, not as a burden, because close connection with (or even worse, immersion in) the intricacies of artefacts and archaeological contexts supposedly aggravates the problem of bias. The machine, in this optic, is framed as the gatekeeper to an observer-independent reality – which to the backdoor often not only re-introduces Platonian/Aristotelian pledges to a quasi-eternal fabric of reality that only needs to be “discovered” by applying the right (broadly nonhuman) means, it is also largely inconsistent with defendable and currently debated conceptions of scientific objectivity that do not fall prey to dogma. Furthermore, current discussions on the open AI ChatGPT have exposed the enormous and still under-reflected dangers of leaning into radical renderings of machine epistemology: precisely because of the principles of automation and the irreducible theory-ladenness of all data, ecologies such as ChatGPT tend to reinforce the tacit epistemological background structures on which they operate and in this way can become collaborators in the legitimization and justification of the status quo (which again counteracts the potential for novelty) – they reproduce supposedly established patterns of thought. This is why, among other things, machines and AI can quickly become perpetuators of parochial and neocolonial projects – their supposed authority creates a sense of impartiality that shields against any possible critique. With Lucas, we can thus perhaps cautiously say that what is required in computational archaeology is to defuse the authority of the machine in favour of a new community archaeology that includes machines as (fallible) co-workers. Radically put, computers and AI should be recognized as subjects themselves, and treated as such, with interesting perspectives on team science and collaborative practice.

Bibliography 1. Lucas, G. (2022). Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology. https:/doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7620824. 2. Kristiansen, K. (2014). Towards a New Paradigm? The Third Science Revolution and its Possible Consequences in Archaeology. Current Swedish Archaeology 22, 11–34. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2014.01. 3. Kristiansen, K. (2022). Archaeology and the Genetic Revolution in European Prehistory. Elements in the Archaeology of Europe. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009228701 4. Eisenhower, M. S. (1964). The Third Scientific Revolution. Science News 85, 322/332. https://www.sciencenews.org/archive/third-scientific-revolution. 5. The ‘Third Science Revolution’ in Archaeology. http://www.eaa2017maastricht.nl/theme4 (March 16, 2023). 6. Ribeiro, A. (2019). Science, Data, and Case-Studies under the Third Science Revolution: Some Theoretical Considerations. Current Swedish Archaeology 27, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2019.06 7. Samida, S. (2019). “Archaeology in times of scientific omnipresence” in Archaeology, History and Biosciences: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, pp. 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110616651 8. Sørensen, T. F.. (2017). The Two Cultures and a World Apart: Archaeology and Science at a New Crossroads. Norwegian Archaeological Review 50, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2017.1367031 9. Anderson, C. (2008). The end of theory: The data deluge makes the scientific method obsolete. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/. 10. Gattiglia, G. (2015). Think big about data: Archaeology and the Big Data challenge. Archäologische Informationen 38, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.11588/ai.2015.1.26155 11. Hackett, E. J. (2008). The handbook of science and technology studies, Third edition, MIT Press/Society for the Social Studies of Science. 12. Ankeny, R., Chang, H., Boumans, M. and Boon, M. (2011). Introduction: philosophy of science in practice. Euro Jnl Phil Sci 1, 303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-011-0036-4 13. Soler, L., Zwart, S., Lynch, M., Israel-Jost, V. (2014). Science after the Practice Turn in the Philosophy, History, and Social Studies of Science, Routledge. 14. Latour, B. and Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: the construction of scientific facts, Princeton University Press. 15. Chapman, R. and Wylie, A. (2016) Evidential reasoning in archaeology, Bloomsbury Academic. 16. Greve, J. and Schnabel, A. (2011). Emergenz: zur Analyse und Erklärung komplexer Strukturen, Suhrkamp. 17. Shapin, S., Schaffer, S. and Hobbes, T. (1985). Leviathan and the air-pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life, including a translation of Thomas Hobbes, Dialogus physicus de natura aeris by Simon Schaffer, Princeton University Press. 18. Galison, P. L. and Stump, D. J. (1996).The Disunity of Science: Boundaries, Contexts, and Power, Stanford University Press. 19. Pepper, S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print, University of California Press. 20. Hussain, S. T. (2019). The French-Anglophone divide in lithic research: A plea for pluralism in Palaeolithic Archaeology, Open Access Leiden Dissertations. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/69812 21. A. Wylie, A. (2015). “A plurality of pluralisms: Collaborative practice in archaeology” in Objectivity in Science, pp. 189-210, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14349-1_10 | Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology | Gavin Lucas | <p>In this paper, I will explore some of the implications of machine learning for archaeological method and theory. Against a back-drop of the rise of Big Data and the Third Science Revolution, what lessons can be drawn from the use of new digital... | Computational archaeology, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | Anonymous, Rachel Crellin | 2022-10-31 15:25:38 | View | |

31 Jan 2024

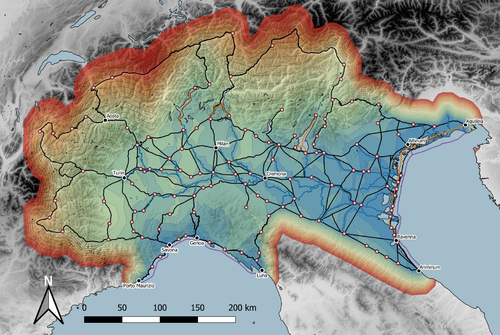

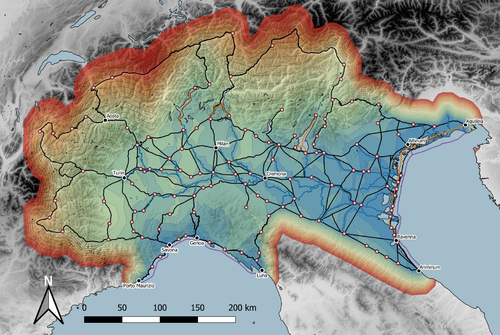

Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman periodJames Page https://zenodo.org/records/7971399Modelling Roman Transport Infrastructure in Northern ItalyRecommended by Andrew McLean based on reviews by Pau de Soto and Adam PažoutStudies of the economy of the Roman Empire have become increasingly interdisciplinary and nuanced in recent years, allowing the discipline to make great strides in data collection and importantly in the methods through which this increasing volume of data can be effectively and meaningfully analysed [see for example 1 and 2]. One of the key aspects of modelling the ancient economy is understanding movement and transport costs, and how these facilitated trade, communication and economic development. With archaeologists adopting more computational techniques and utilising GIS analysis beyond simply creating maps for simple visualisation, understanding and modelling the costs of traversing archaeological landscapes has become a much more fruitful avenue of research. Classical archaeologists are often slower to adopt these new computational techniques than others in the discipline. This is despite (or perhaps due to) the huge wealth of data available and the long period of time over which the Roman economy developed, thrived and evolved. This all means that the Roman Empire is a particularly useful proving ground for testing and perfecting new methodological developments, as well as being a particularly informative period of study for understanding ancient human behaviour more broadly. This paper by Page [3] then, is well placed and part of a much needed and growing trend of Roman archaeologists adopting these computational approaches in their research. Page’s methodology builds upon De Soto’s earlier modelling of transport costs [4] and applies it in a new setting. This reflects an important practice which should be more widely adopted in archaeology. That of using existing, well documented methodologies in new contexts to offer wider comparisons. This allows existing methodologies to be perfected and tested more robustly without reinventing the wheel. Page does all this well, and not only builds upon De Soto’s work, but does so using a case study that is particularly interesting with convincing and significant results. As Page highlights, Northern Italy is often thought of as relatively isolated in terms of economic exchange and transport, largely due to the distance from the sea and the barriers posed by the Alps and Apennines. However, in analysing this region, and not taking such presumptions for granted, Page quite convincingly shows that the waterways of the region played an important role in bringing down the cost of transport and allowed the region to be far more interconnected with the wider Roman world than previous studies have assumed. This article is clearly a valuable and important contribution to our understanding of computational methods in archaeology as well as the economy and transport network of the Roman Empire. The article utilises innovative techniques to model transport in an area of the Roman Empire that is often overlooked, with the economic isolation of the area taken for granted. Having high quality research such as this specifically analysing the region using the most current methodologies is of great importance. Furthermore, developing and improving methodologies like this allow for different regions and case studies to be analysed and directly compared, in a way that more traditional analyses simply cannot do. As such, Page has demonstrated the importance of reanalysing traditional assumptions using the new data and analyses now available to archaeologists. References [1] Brughmans, T. and Wilson, A. (eds.) (2022). Simulating Roman Economies: Theories, Methods, and Computational Models. Oxford. [2] Dodd, E.K. and Van Limbergen, D. (eds.) (2024). Methods in Ancient Wine Archaeology: Scientific Approaches in Roman Contexts. London ; New York. [3] Page, J. (2024). Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman period, Zenodo, 7971399, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7971399 [4] De Soto P (2019). Network Analysis to Model and Analyse Roman Transport and Mobility. In: Finding the Limits of the Limes. Modelling Demography, Economy and Transport on the Edge of the Roman Empire. Ed. by Verhagen P, Joyce J, and Groenhuijzen M. Springer Open Access, pp. 271–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04576-0_13 | Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman period | James Page | <p>Northern Italy has often been characterised as an isolated and marginal area during the Roman period, a region constricted by mountain ranges and its distance from major shipping lanes. Historians have frequently cited these obstacles, alongsid... |  | Classic, Computational archaeology | Andrew McLean | 2023-05-28 15:11:31 | View | |

14 Mar 2024

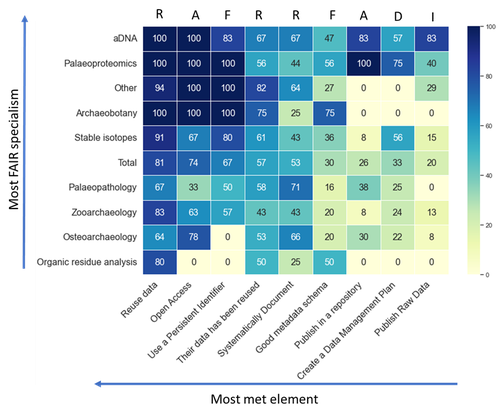

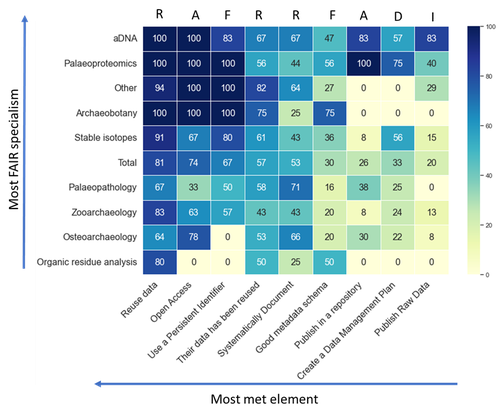

How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data ReusableLien-Talks, Alphaeus https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910FAIR data in bioarchaeology - where are we at?Recommended by Claudia Speciale based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Emma Karoune, Jan Kolar and 2 anonymous reviewers

The increasing reliance on digital and big data in archaeology is pushing the scientific community more and more to reconsider their storing and use [1, 2]. Furthermore, the openness and findability in the way these data are shared represent a key matter for the growth of the discipline, especially in the case of bioarchaeology and archaeological sciences [3]. In this paper, [4] the author presents the result of a survey targeted on UK bioarchaeologists and then extended worldwide. The paper maintains the structure of a report as it was intended for the conference it was part of (CAA 2023, Amsterdam) but it represents the first public outcome of an inquiry on the bioarchaeological scientific community. A reflection on ourselves and our own practices. Are all the disciplines adhering to the same policies? Do any bioarchaeologist use the same protocols and formats? Are there any differences in between the domains? Is the Needs Analysis fulfilling the questions? The results, obtained through an accurate screening to avoid distortions, are creating an intriguing picture on the current state of "fairness" and highlighting how Institutions' rules and policies can and should indicate the correct workflow to follow. In the end, the wide application of the FAIR principles will contribute significantly to the growth of the disciplines and to create an environment where the users are not just contributors, but primary beneficiaries of the system. [1] Huggett j. (2020). Is Big Digital Data Different? Towards a New Archaeological Paradigm, Journal of Field Archaeology, 45:sup1, S8-S17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2020.1713281 [2] Nicholson C., Kansa S., Gupta N. and Fernandez R. (2023). Will It Ever Be FAIR?: Making Archaeological Data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Advances in Archaeological Practice 11 (1): 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2022.40 [3] Plomp E., Stantis C., James H.F., Cheung C., Snoeck C., Kootker L., Kharobi A., Borges C., Reynaga D.K.M., Pospieszny Ł., Fulminante, F., Stevens, R., Alaica, A. K., Becker, A., de Rochefort, X. and Salesse, K. (2022). The IsoArcH initiative: Working towards an open and collaborative isotope data culture in bioarchaeology. Data in brief, 45, p.108595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2022.108595 [4] Lien-Talks, A. (2024). How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable. Zenodo, 8139910, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8139910 | How FAIR is Bioarchaeological Data: with a particular emphasis on making archaeological science data Reusable | Lien-Talks, Alphaeus | <p>Bioarchaeology, which encompasses the study of ancient DNA, osteoarchaeology, paleopathology, palaeoproteomics, stable isotopes, and zooarchaeology, is generating an ever-increasing volume of data as a result of advancements in molecular biolog... |  | Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Zooarchaeology | Claudia Speciale | 2023-07-12 19:12:44 | View | |

14 Nov 2023

Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics ClassroomStephan, Robert https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8221286Learning with Archaeogaming? A study based on student feedbackRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Jeremiah McCall and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jeremiah McCall and 1 anonymous reviewer

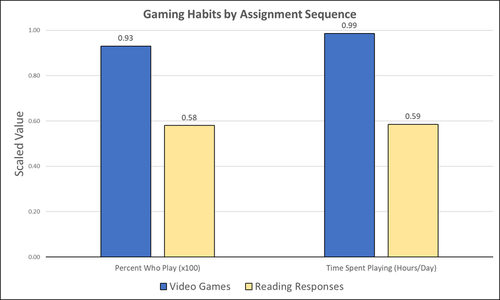

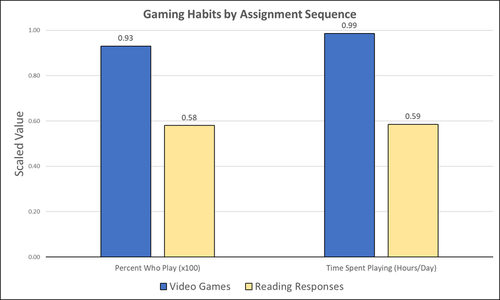

This paper (Stephan 2023) is about the use of video games as a pedagogical tool in class. Instead of taking the perspective of a lecturer, the author seeks the student’s perspectives to evaluate the success of an interactive teaching method at the crossroads of history, archaeology, and classics. The paper starts with a literature review, that highlights the intensive use of video games among college students and high schoolers as well as the impact video games can have on learning about the past. The case study this paper is based on is made with the game Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, which is introduced in the next part of the paper as well as previous works on the same game. The author then explains his method, which entailed the tasks students had to complete for a class in classics. They could either choose to play a video game or more classically read some texts. After the tasks were done, students filled out a 14-question-survey to collect data about prior gaming experience, assignment enjoyment, and other questions specific to the assignments. The results were based on only a fraction of the course participants (n=266) that completed the survey (n=26), which is a low number for doing statistical analysis. Besides some quantitative questions, students had also the possibility to freely give feedback on the assignments. Both survey types (quantitative answers and qualitative feedback) solely relied on the self-assessment of the students and one might wonder how representative a self-assessment is for evaluating learning outcomes. Both problems (size of the survey and actual achievements of learning outcomes) are getting discussed at the end of the paper, that rightly refers to its results as preliminary. I nevertheless think that this survey can help to better understand the role that video games can play in class. As the author rightly claims, this survey needs to be enhanced with a higher number of participants and a better way of determining the learning outcomes objectively. This paper can serve as a start into how we can determine the senseful use of video games in classrooms and what students think about doing so. References

Stephan, R. (2023). Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics Classroom, Zenodo, 8221286, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8221286

| Student Feedback on Archaeogaming: Perspectives from a Classics Classroom | Stephan, Robert | <p>This study assesses student feedback from the implementation of Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey as a teaching tool in a lower level, general education Classics course (CLAS 160B1 - Meet the Ancients: Gateway to Greece and Rome). In this course, which... |  | Antiquity, Classic, Mediterranean | Sebastian Hageneuer | Anonymous, Jeremiah McCall | 2023-08-07 16:45:31 | View |

02 Feb 2024

Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley CollectionRaykovska Miglena, Jones Kristen, Klecherova Hristina, Alexandrov Stefan, Petkov Nikolay, Hristova Tanya, Ivanov Georgi https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8027548Out of the storeroom and into the virtualRecommended by Jitte Waagen based on reviews by Alicia Walsh and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Alicia Walsh and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (Raykovska et al. 2023) discusses the digital documentation techniques and development of a virtual exhibition for artefacts retrieved from the necropolis of Baley, Bulgaria. The principal aim of this particular project is a solid one, trying to provide a solution to display artefacts that would otherwise remain hidden in museum storerooms. The paper describes how through a combination of 3D scanning and photogrammetry high quality 3D models have been produced, and provide content for an online virtual exhibition for the scientific community but also the larger public. It is a well-written and concise paper, in which the information on developed methods and techniques are transparently described, and various important aspects of digitization workflows, such as the importance of storing raw data, are addressed. The paper is a timely discussion on this subject, as strategies to develop digital artefact collections and what to do with those are increasingly being researched. Specifically, it discusses a workflow and its results, both in great detail. Although critical reflection on the process, goals and results from various perspectives would have been a valuable addition to the paper (cf., Jeffra 2020, Paardekoper 2019), it nonetheless provides a good practice example of how to approach the creation of a virtual museum. Those who consider projects concerning digital documentation of archaeological artefacts as well as the creation of virtual spaces to use those in for research, education or valorisation purposes would do well to read this paper carefully. References Jeffra, C., Hilditch, J., Waagen, J., Lanjouw, T., Stoffer, M., de Gelder, L., and Kim, M. J. (2020). Blending the Material and the Digital: A Project at the Intersection of Museum Interpretation, Academic Research, and Experimental Archaeology. The EXARC Journal, 2020(4). https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10541 Paardekooper, R.P. (2019). Everybody else is doing it, so why can’t we? Low-tech and High-tech approaches in archaeological Open-Air Museums. The EXARC Journal, 2019(4). https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10457/ Raykovska, M., Jones, K., Klecherova, H., Alexandrov, S., Petkov, N., Hristova, T., and Ivanov, G. (2023). Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley Collection. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10091870 | Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley Collection | Raykovska Miglena, Jones Kristen, Klecherova Hristina, Alexandrov Stefan, Petkov Nikolay, Hristova Tanya, Ivanov Georgi | <p>Over the past decade, virtual reality has been quickly growing in popularity across disciplines including the field of archaeology and cultural heritage. Despite numerous artifacts being uncovered each year by archaeological excavations around ... |  | Ceramics, Computational archaeology, Conservation/Museum studies | Jitte Waagen | 2023-06-12 14:02:44 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer