Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 Oct 2023

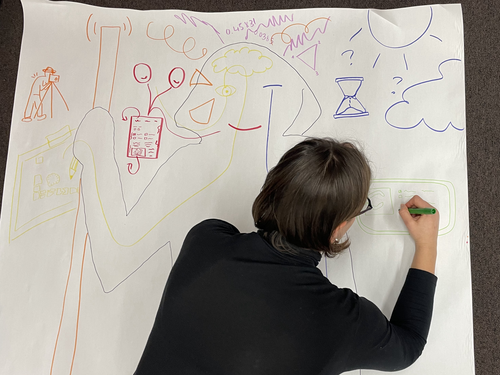

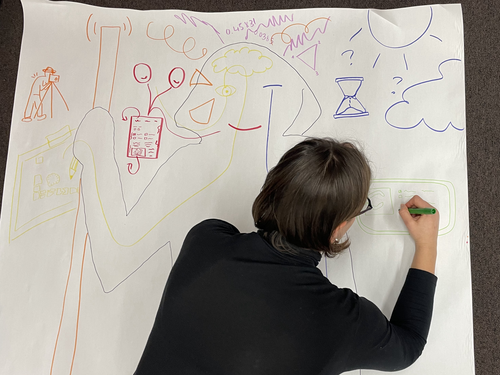

Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice.Araar, Leila; Morgan, Colleen; Fowler, Louise https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7990581Understanding archaeological documentation through a participatory, arts-based approachRecommended by Nicolo Dell'Unto based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThis paper presents the use of a participatory arts-based methodology to understand how digital and analogue tools affect individuals' participation in the process of archaeological recording and interpretation. The preliminary results of this work highlight the importance of rethinking archaeologists' relationship with different recording methods, emphasising the need to recognise the value of both approaches and to adopt a documentation strategy that exploits the strengths of both analogue and digital methods. Although a larger group of participants with broader and more varied experience would have provided a clearer picture of the impact of technology on current archaeological practice, the article makes an important contribution in highlighting the complex and not always easy transition that archaeologists trained in analogue methods are currently experiencing when using digital technology. This is assessed by using arts-based methodologies to enable archaeologists to consider how digital technologies are changing the relationship between mind, body and practice. I found the range of experiences described in the papers by the archaeologists involved in the experiment particularly interesting and very representative of the change in practice that we are all experiencing. As the article notes, the two approaches cannot be directly compared because they offer different possibilities: if analogue methods foster a deeper connection with the archaeological material, digital documentation seems to be perceived as more effective in terms of data capture, information exchange and data sharing (Araar et al., 2023). It seems to me that an important element to consider in such a study is the generational shift and the incredible divide between native and non-native digital. The critical issues highlighted in the paper are central and provide important directions for navigating this ongoing (digital) transition. References Araar, L., Morgan, C. and Fowler, L. (2023) Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice., Zenodo, 7990581, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7990581 | Body Mapping the Digital: Visually representing the impact of technology on archaeological practice. | Araar, Leila; Morgan, Colleen; Fowler, Louise | <p>This paper uses a participatory, art-based methodology to understand how digital and analog tools impact individuals' experience and perceptions of archaeological recording. Body mapping involves the co-creation of life-sized drawings and narra... |  | Computational archaeology, Theoretical archaeology | Nicolo Dell'Unto | 2023-06-01 09:06:52 | View | |

05 Jan 2024

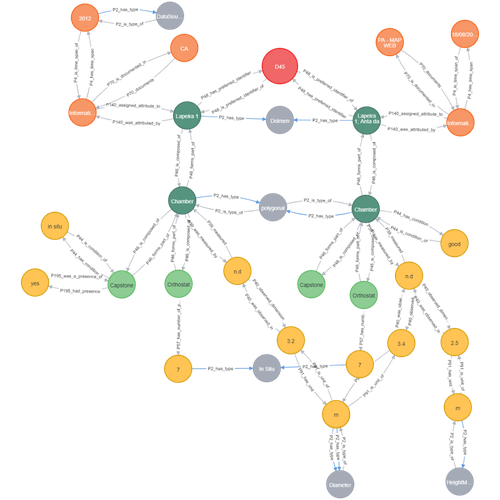

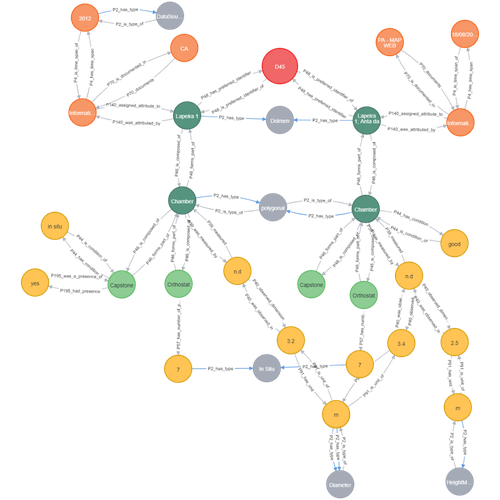

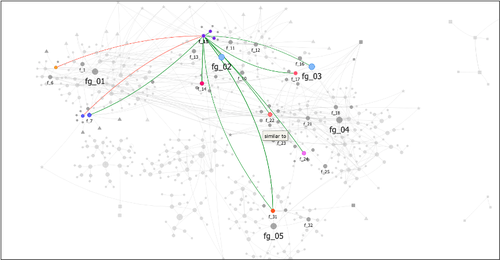

Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graphAriele Câmara, Ana de Almeida, João Oliveira https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981230Informative description of a project implementing a CIDOC-CRM based native graph database for representing megalithic informationRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper “Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph” describes an interesting endeavour of developing and implementing a CIDOC-CRM based knowledge graph using a native graph database (Neo4J) to represent megalithic information (Câmara et al. 2023). While there are earlier examples of using native graph databases and CIDOC-CRM in diverse heritage contexts, the present paper is useful addition to the literature as a detailed description of an implementation in the context of megalithic heritage. The paper provides a demonstration of a working implementation, and guidance for future projects. The described project is also documented to an extent that the paper will open up interesting opportunities to compare the approach to previous and forthcoming implementations. The same applies to the knowledge graph and use of CIDOC-CRM in the project. Readers interested in comparing available technologies and those who are developing their own knowledge graphs might have benefited of a more detailed description of the work in relation to the current state-of-the-art and what the use of a native graph database in the built-heritage contexts implies in practice for heritage documentation beyond that it is possible and it has potentially meaningful performance-related advantages. While also the reasons to rely on using plain CIDOC-CRM instead of extensions could have been discussed in more detail, the approach demonstrates how the plain CIDOC-CRM provides a good starting point to satisfy many heritage documentation needs. As a whole, the shortcomings relating to positioning the work to the state-of-the-art and reflecting and discussing design choices do not reduce the value of the paper as a valuable case description for those interested in the use of native graph databases and CIDOC-CRM in heritage documentation in general and the documentation of megalithic heritage in particular. ReferencesCâmara, A., de Almeida, A. and Oliveira, J. (2023). Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph, Zenodo, 7981230, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7981230 | Transforming the CIDOC-CRM model into a megalithic monument property graph | Ariele Câmara, Ana de Almeida, João Oliveira | <p>This paper presents a method to store information about megalithic monuments' building components as graph nodes in a knowledge graph (KG). As a case study we analyse the dolmens from the region of Pavia (Portugal). To build the KG, information... |  | Computational archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-29 13:46:49 | View | |

10 Jun 2024

Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times.Artur Ribeiro https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10567441The Postmodern Predicament of Type-Thinking in ArchaeologyRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by Gavin Lucas, Miguel John Versluys and Anna S. Beck based on reviews by Gavin Lucas, Miguel John Versluys and Anna S. Beck

“Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times” by A. Ribeiro (1) offers some timely, critical and creative reflections on the manifold struggles of and disappointments in type-thinking and typological approaches in recent archaeological scholarship. Ribeiro insightfully situates what has been identified as a “crisis” in archaeological typo-praxis in the historical conditions of postmodernity and late capitalism themselves. The author thereby attempts what he himself considers “quite hard”, namely “to understand the current Zeitgeist and how it affects how we think and do archaeology” (p. 4). This provides a sort of historical epistemology of the present which can of course only be preliminary and incomplete as it crystallizes, takes shape, and transforms as we write these lines, is available only in fragments and hints, and is generally difficult to talk about and describe as we (the author included) lack critical distance – present-day archaeologists and fellow academics are both enfolded in postmodernity and continue to contribute to its logics and trajectories. Ribeiro’s key argument is provocative as it is interesting: he contends that archaeologists’ difficulties of coming to terms with types and typologies – staple knowledge practices of the discipline ever since – are a symptom of the changing cultural matrix of our times. The diagnosis is multilayered and complex, and Ribeiro at times only scratches the surface of what may be at stake here as he openly admits himself. At the core of his proposal is a shift in attention away from classical questions of epistemological rank, which in archaeology have tended to orbit the contentious issue of the reality of types (see also 2). Instead of foregrounding the question of type-realities – whether types, once identified, can be meaningfully said to exist and to represent something significant in the world – archaeologists are urged to recognize that typo-praxis is culturally saturated in at least two profound ways. First, devising and mobilizing types and typologies is a cultural practice itself – it may indeed have long been a foundational ‘cultural technique’ (Kulturtechnik) (3) of archaeology as a disciplined community-venture of methodical knowledge production. Typo-centric understandings of the archaeological record are quite akin to definition-centric apprehensions of the same as in both cases order, discreteness, and one-to-one correspondence are considered overriding epistemic virtues and credible pointers to a subject-independent “reality”. As such, these practices have a location of their own and they may thus notably conflict with the particularities of alternate and ever-mutating phenomenal realities and historical conditions. Discreteness may for instance lose its paradigmatic status as a descriptor of worldly order, and this is precisely what Ribeiro argues to have happened in the wake of postmodern transformations, influentially said to have deeply reconfigured the relation between the local and the global, at times even superseding such distinctions altogether. When coupled to questions of reality, types, in a similar fashion as definitions, quickly become vehicles to affirm epistemic power and knowledge authority and so help certify certain kinds of realities while supressing others. This is the paradox of modernity: to insist on monolithic understandings of the world while professing radical difference. Second, and for Ribeiro more importantly, typo-praxis is not just subject to cultural variation and thus by implication is plural, it also always has its proper associated cultural milieu in which it exerts some sort of efficacy, i.e. enables action and insight. Ribeiro maintains that this sort of efficacy has become contentious under postmodern conditions and this is because culture, under the gaze of global consumerism, has lost much of its classical significance, and as “hyperculture” (4) developed new logics, significations, and material culture correspondences, essentially “flattening” the highly textured and differentiated world of modernity (p. 6). Some of these new configurations sharply violate the expectations of traditional views of culture. The postmodern situation has in this way effectively emerged as a resistant force proffering much caution and growing scepticism among archaeologists and other academics alike as received ideas about “types” and “cultures” do not seem to work anymore the same way as before. The credibility of different modes of typo-praxis, archaeological or not, in other words, may depend much more on the cultural ecology of lived experience and contemporary diagnosis than is often realized. With Ribeiro, we may say that culture concepts and type concepts are indeed co-constitutive, and what sort of types and typologies archaeologists can persuasively deploy thus also depends greatly on how we construct the link between culture and type, and how (well) we grapple with our own realities and the lessons we draw from them – yet another important reminder of how our own subjectivities figure in such foundational debates (see esp. 5). The crisis of typo-praxis in archaeology, then, is intricately linked to the crisis of modernity, broached by Ribeiro with the labels of postmodernity and late capitalism. Upon reflection, this is not surprising at all since Tylor’s (6) influential definition of culture for example, which is extensively referenced in the paper, was both reflective of and conducive to the project of modernity and its distinctive historical formations such as empire and colonialism. Ribeiro reminds us that questions of justification and credibility, be it in the domain of type-thinking or other epistemic contexts, can never be fully divorced from the contemporary situation, and archaeologists thus need to be vigilant observers of the present, too. Typo-praxis ultimately is motivated by and draws authority from what Foucault (7) has called épistémè, the totality of pertinent parameters forming the historical a priori of understanding or the guiding unconsciousness of subjectivity within a given epoch. The crisis of archaeological typo-praxis, in this view, signifies a calling into question of the historical a priori on which much traditional type-work in archaeology was premised. Archaeologists still have to come to terms with the implications and consequences of this assessment. “Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times” offers a first poignant analysis of some of these challenges of postmodern archaeological type-thinking.

Bibliography 1. Ribeiro, A. (2024). Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times. Zenodo, 10567441, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10567441 2. Hussain, S. T. (2024). The Loss of Typological Innocence: An Archaeology of Archaeological Typo-Praxis. Zenodo, 10567441. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10547264 3. Macho, T. (2013). Second-Order Animals: Cultural Techniques of Identity and Identification. Theory, Culture & Society 30, 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413499189 4. Han, B.-C. (2022). Hyperculture: culture and globalization (Polity Press). 5. Frank, A., Gleiser, M. and Thompson, E. (2024). The blind spot: why science cannot ignore human experience (The MIT Press). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13711.001.0001 6. E. B. Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom (J. Murray). 7. Foucault, M. (2007). The order of things: an archaeology of the human sciences, Repr (Routledge). | Hypercultural types: archaeological objects in fast times. | Artur Ribeiro | <p>Although artifact typologies still play a big role in archaeology, they have certainly lost some repute in recent decades. More than just a collection of items with similar attributes, typologies are a reflection of cultural behaviour and pract... |  | Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2024-01-25 13:40:08 | View | |

06 Oct 2023

From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editionsAuth. Frederic; Rösler, Katja; Domscheit, Wenke; Hofmann, Kerstin P. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7304578Revitalising archaeological corpus publications through digitisation – the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae as exemplary casesRecommended by Felix Riede, Sébastien Plutniak and Shumon Tobias Hussain and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova

The paper entitled “From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions” submitted by Frederic Auth and colleagues discusses how those rich and often meticulously illustrated catalogues of particular find classes that exist in many corners of archaeology can be brought to the cutting edge of contemporary research through digitisation. This paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology, taxonomy, classification theory, and computational approaches in archaeology. Auth et al. (2023) begin with outlining the useful notion of the ‘thing-edition’ originally coined by Kerstin Hofmann in the context of her work with the many massive corpora of finds that have characterised, in particular, earlier archaeological knowledge production in Germany (Hofmann et al. 2019; Hofmann 2018). This work critically examines changing trends in the typological characterisation and recording of various find categories, their theoretical foundations or lack thereof and their legacy on contemporary practice. The present contribution focuses on what happens with such corpora when they are integrated into digitisation projects, specifically the efforts by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), the so-called iDAI.world and in regard to two Roman-era material culture groups, the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum (Roman finds from beyond the empire’s borders in eight printed volumes covering thousands of finds of various categories), and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae (Roman plain ware). Drawing on Bruno Latour’s (2005) actor-network theory (ANT), Auth et al. discuss and reflect on the challenges met and choices to be made when thing-editions are to be transformed into readily accessible data, that is as linked to open, usable data. The intellectual and infrastructural workload involved in such digitisation projects is not to be underestimated. Here, the contribution by Auth et al. excels in the manner that it does not present the finished product – the fully digitised corpora – but instead offers a glimpse ‘under the hood’ of the digitisation process as an interaction between analogue corpus, research team, and the technologies at hand. These aspects were rarely addressed in the literature, rooted in the 1970s early work (Borillo and Gardin 1974; Gaines 1981), on archaeological computerised databases, focused on technical dimensions (see Rösler 2016 for an exception). Their paper can so also be read in the broader context of heterogeneous computer-assisted knowledge ecologies and ‘mangles of practice’ (see Pickering and Guzik 2009) in which practitioners and technological structures respond to each other’s needs and attempt to cooperate in creative ways. As such, Auth et al.’s considerations not least offer valuable resources for Science and Technology Studies-inspired discussions on the cross-fertilization of archaeological theory, practice and currently emerging material and virtual research infrastructures and can be read in conjunction to Gavin Lucas’ (2022) paper on ‘machine epistemology’ due to appear in the same volume. Perhaps more importantly, however, the work by Auth and colleagues (2023) exemplifies the due diligence required in not merely turning a catalogue from paper to digital document but in transforming such catalogues into long-lasting and patently usable repositories of generations of scholars to come. Deploying the Latourian notions of trade-off and recursive reference, Auth et al. first examine the structure, strengths, and weakness of the two corpora before moving on to showing how the freshly digitised versions offer new and alternative ways of analysing the archaeological material at hand, notably through immediate visualisation opportunities, through ceramic form combinations, and relational network diagrams based on the data inherent in the respective thing-editions. Catalogues including basic descriptions and artefact illustrations exist for most if not all archaeological periods. They constitute an essential backbone of archaeological work as repeated access to primary material is impractical if not impossible. The catalogues addressed by Auth et al. themselves reflect major efforts on behalf of archaeological experts to arrive at clear and operational classifications in a pre-computerised era. The continued and expanded efforts by Auth and colleagues build on these works and clearly demonstrate the enormous analytical potential to make such data not merely more accessible but also more flexibly interoperable. Their paper will therefore be an important reference for future work with similar ambitions facing similar challenges. References Auth, Frederic, Katja Rösler, Wenke Domscheit, and Kerstin P. Hofmann. 2023. “From Paper to Byte: A Workshop Report on the Digital Transformation of Two Thing Editions.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8214563 Borillo, Mario, and Jean-Claude Gardin. 1974. Les Banques de Données Archéologiques. Marseille: Éditions du CNRS. Gaines, Sylvia W., ed. 1981. Data Bank Applications in Archaeology. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. Hofmann, Kerstin P. 2018. “Dingidentitäten Und Objekttransformationen. Einige Überlegungen Zur Edition von Archäologischen Funden.” In Objektepistemologien. Zum Verhältnis von Dingen Und Wissen, edited by Markus Hilgert, Kerstin P. Hofmann, and Henrike Simon, 179–215. Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 59. Berlin: Edition Topoi. https://dx.doi.org/10.17171/3-59 Hofmann, Kerstin P., Susanne Grunwald, Franziska Lang, Ulrike Peter, Katja Rösler, Louise Rokohl, Stefan Schreiber, Karsten Tolle, and David Wigg-Wolf. 2019. “Ding-Editionen. Vom Archäologischen (Be-)Fund Übers Corpus Ins Netz.” E-Forschungsberichte des DAI 2019/2. E-Forschungsberichte Des DAI. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2236/6674 Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lucas, Gavin. 2022. “Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7622162 Pickering, Andrew, and Keith Guzik, eds. 2009. The Mangle in Practice: Science, Society, and Becoming. The Mangle in Practice. Science and Cultural Theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Rösler, Katja. 2016. “Mit Den Dingen Rechnen: ‚Kulturen‘-Forschung Und Ihr Geselle Computer.” In Massendinghaltung in Der Archäologie. Der Material Turn Und Die Ur- Und Frühgeschichte, edited by Kerstin P. Hofmann, Thomas Meier, Doreen Mölders, and Stefan Schreiber, 93–110. Leiden: Sidestone Press. | From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions | Auth. Frederic; Rösler, Katja; Domscheit, Wenke; Hofmann, Kerstin P. | <p>One specific form of publication for archaeological objects are catalogues, atlases and corpora. Kerstin Hofmann has introduced the term ‘Ding-Editionen’ (thing editions) for this category of publications that present their data in lists, short... |  | Antiquity, Computational archaeology, Dating, Theoretical archaeology | Felix Riede | 2022-11-08 16:00:49 | View | |

03 Nov 2023

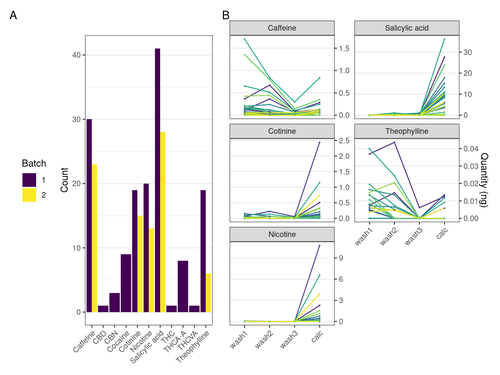

Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch populationBartholdy, Bjørn Peare; Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B.; Sørensen, Lambert K.; Casna, Maia; Hoogland, Menno; Historisch Genootschap Beemster; Henry, Amanda G. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7649150Detection of plant-derived compounds in XIXth c. Dutch dental calculusRecommended by Louise Le Meillour based on reviews by Mario Zimmerman and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Mario Zimmerman and 2 anonymous reviewers

The advent of biomolecular methods has certainly increased our overall comprehension of archaeological societies. One of the materials of choice to perform ancient DNA or proteomics analyses is dental calculus[1,2], a mineralised biofilm formed during the life of one individual. Research conducted in the past few decades has demonstrated the potential of dental calculus to retrieve information about past societies health[3–6], diet[7–11], and more recently, as a putative proxy for isotopic analyses[12].

Bartholdy et al. utilised the developed LC-MS/MS method to 41 buried individuals, most of them bearing pipe notches on their teeth, from the cemetery of the 19th rural settlement of Middenbeemster, the Netherlands. Along with dental calculus sampling and analysis, they undertook the skeletal and dental examination of all of the specimens in order to assess sex, age-at-death, and pathology on the two tissues. The results obtained on the dental calculus of the sampled individuals show probable consumption of tea, coffee and tobacco indicated by the detection of the various plant compounds and associated metabolites (caffeine, nicotine and salicylic acid, amongst others). The authors were able to place their results in perspective and propose several interpretations concerning the ingestion of plant-derived products, their survival in dental calculus and the importance of their findings for our overall comprehension of health and habits of the XIXth c. Dutch population. The paper is well-written and accessible to a non-specialist audience, maximising the impact of their study. I personally really enjoyed handling this manuscript that is not only a good piece of scientific literature but also a pleasant read, the reason why I warmly recommend this paper to be accessible through PCI Archaeology. References 1. Fagernäs, Z. and Warinner, C. (2023) Dental Calculus. in Handbook of Archaeological Sciences 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119592112.ch28 2. Wright, S. L., Dobney, K. & Weyrich, L. S. (2021) Advancing and refining archaeological dental calculus research using multiomic frameworks. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 7, 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2021.1882122 3. Fotakis, A. K. et al. (2020) Multi-omic detection of Mycobacterium leprae in archaeological human dental calculus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 375, 20190584. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0584 4. Warinner, C. et al. (2014) Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nat. Genet. 46, 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2906 5. Weyrich, L. S. et al. (2017) Neanderthal behaviour, diet, and disease inferred from ancient DNA in dental calculus. Nature 544, 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21674 6. Jersie-Christensen, R. R. et al. (2018) Quantitative metaproteomics of medieval dental calculus reveals individual oral health status. Nat. Commun. 9, 4744. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07148-3 7. Hendy, J. et al. (2018) Proteomic evidence of dietary sources in ancient dental calculus. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.0977 8. Wilkin, S. et al. (2020) Dairy pastoralism sustained eastern Eurasian steppe populations for 5,000 years. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1120-y 9. Bleasdale, M. et al. (2021) Ancient proteins provide evidence of dairy consumption in eastern Africa. Nat. Commun. 12, 632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20682-3 10. Warinner, C. et al. (2014) Direct evidence of milk consumption from ancient human dental calculus. Sci. Rep. 4, 7104. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07104 11. Buckley, S., Usai, D., Jakob, T., Radini, A. and Hardy, K. (2014) Dental Calculus Reveals Unique Insights into Food Items, Cooking and Plant Processing in Prehistoric Central Sudan. PLoS One 9, e100808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100808 12. Salazar-García, D. C., Warinner, C., Eerkens, J. W. and Henry, A. G. (2023) The Potential of Dental Calculus as a Novel Source of Biological Isotopic Data. in Exploring Human Behavior Through Isotope Analysis: Applications in Archaeological Research (eds. Beasley, M. M. & Somerville, A. D.) 125–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32268-6_6 13. Sørensen, L. K., Hasselstrøm, J. B., Larsen, L. S. and Bindslev, D. A. (2021) Entrapment of drugs in dental calculus - Detection validation based on test results from post-mortem investigations. Forensic Sci. Int. 319, 110647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110647 14. Bartholdy, Bjørn Peare, Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B., Sørensen, Lambert K., Casna, Maia, Hoogland, Menno, Historisch Genootschap Beemster and Henry, Amanda G. (2023) Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch population, Zenodo, 7649150, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7649150 | Multiproxy analysis exploring patterns of diet and disease in dental calculus and skeletal remains from a 19th century Dutch population | Bartholdy, Bjørn Peare; Hasselstrøm, Jørgen B.; Sørensen, Lambert K.; Casna, Maia; Hoogland, Menno; Historisch Genootschap Beemster; Henry, Amanda G. | <p>Dental calculus is an excellent source of information on the dietary patterns of past populations, including consumption of plant-based items. The detection of plant-derived residues such as alkaloids and their metabolites in dental calculus pr... |  | Bioarchaeology, Post-medieval | Louise Le Meillour | Mario Zimmerman, Anonymous | 2023-07-31 17:21:40 | View |

13 Jan 2024

Dealing with post-excavation data: the Omeka S TiMMA web-databaseBastien Rueff https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7989904Managing Archaeological Data with Omeka SRecommended by Jonathan Hanna based on reviews by Electra Tsaknaki and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Electra Tsaknaki and 1 anonymous reviewer

Managing data in archaeology is a perennial problem. As the adage goes, every day in the field equates to several days in the lab (and beyond). For better or worse, past archaeologists did all their organizing and synthesis manually, by hand, but since the 1970s ways of digitizing data for long term management and analysis have gained increasing attention [1]. It is debatable whether this ever actually made things easier, particularly given the associated problem of sustainable maintenance and accessibility of the data. Many older archaeologists, for instance, still have reels and tapes full of data that now require a new form of archaeology to excavate (see [2] for an unrealized idea on how to solve this). Today, the options for managing digital archaeological data are limited only by one’s imagination. There are systems built specifically for archaeology, such as Arches [3], Ark [4], Codifi [5], Heurist [6], InTerris Registries [7], OpenAtlas [8], S-Archeo [9], and Wild Note [10], as well as those geared towards museum collections like PastPerfect [11] and CatalogIt [12], among others. There are also mainstream databases that can be adapted to archaeological needs like MS Access [13] and Claris FileMaker [14], as well as various web database apps that function in much the same way (e.g., Caspio [15], dbBee [16], Amazon's Simpledb [17], Sci-Note [18], etc.) — all with their own limitations in size, price, and utility. One could also write the code for specific database needs using pre-built frameworks like those in Ruby-On-Rails [19] or similar languages. And of course, recent advances in machine-learning and AI will undoubtedly bring new solutions in the near future. But let’s be honest — most archaeologists probably just use Excel. That's partly because, given all the options, it is hard to decide the best tool and whether its worth changing from your current system, especially given few real-world examples in the literature. Bastien Rueff’s new paper [20] is therefore a welcomed presentation on the use of Omeka S [21] to manage data collected for the Timbers in Minoan and Mycenaean Architecture (TiMMA) project. Omeka S is an open-source web-database that is based in PHP and MySQL, and although it was built with the goal of connecting digital cultural heritage collections with other resources online, it has been rarely used in archaeology. Part of the issue is that Omeka Classic was built for use on individual sites, but this has now been scaled-up in Omeka S to accommodate a plurality of sites. Some of the strengths of Omeka S include its open-source availability (accessible regardless of budget), the way it links data stored elsewhere on the web (keeping the database itself lean), its ability to import data from common file types, and its multi-lingual support. The latter feature was particularly important to the TiMAA project because it allowed members of the team (ranging from English, Greek, French, and Italian, among others) to enter data into the system in whatever language they felt most comfortable. However, there are several limitations specific to Omeka S that will limit widespread adoption. Among these, Omeka S apparently lacks the ability to export metadata, auto-fill forms, produce summations or reports, or provide basic statistical analysis. Its internal search capabilities also appear extremely limited. And that is not to mention the barriers typical of any new software, such as onerous technical training, questionable long-term sustainability, or the need for the initial digitization and formatting of data. But given the rather restricted use-case for Omeka S, it appears that this is not a comprehensive tool but one merely for data entry and storage that requires complementary software to carry out common tasks. As such, Rueff has provided a review of a program that most archaeologists will likely not want or need. But if one was considering adopting Omeka S for a project, then this paper offers critical information for how to go about that. It is a thorough overview of the software package and offers an excellent example of its use in archaeological practice.

[1] Doran, J. E., and F. R. Hodson (1975) Mathematics and Computers in Archaeology. Harvard University Press. [2] Snow, Dean R., Mark Gahegan, C. Lee Giles, Kenneth G. Hirth, George R. Milner, Prasenjit Mitra, and James Z. Wang (2006) Cybertools and Archaeology. Science 311(5763):958–959. [3] https://www.archesproject.org/ [4] https://ark.lparchaeology.com/ [5] https://codifi.com/ [6] https://heuristnetwork.org/ [7] https://www.interrisreg.org/ [8] https://openatlas.eu/ [9] https://www.skinsoft-lab.com/software/archaelogy-collection-management [10] https://wildnoteapp.com/ [11] https://museumsoftware.com/ [12] https://www.catalogit.app/ [13] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/access [14] https://www.claris.com/filemaker/ [15] https://www.caspio.com/ [16] https://www.dbbee.com/ [17] https://aws.amazon.com/simpledb/ [18] https://www.scinote.net/ [19] https://rubyonrails.org/ [20] Rueff, Bastien (2023) Dealing with Post-Excavation Data: The Omeka S TiMMA Web-Database. peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://zenodo.org/records/7989905 [21] https://omeka.org/

| Dealing with post-excavation data: the Omeka S TiMMA web-database | Bastien Rueff | <p>This paper reports on the creation and use of a web database designed as part of the TiMMA project with the Content Management System Omeka S. Rather than resulting in a technical manual, its goal is to analyze the relevance of using Omeka S in... |  | Buildings archaeology, Computational archaeology | Jonathan Hanna | 2023-05-31 12:16:25 | View | |

11 Jan 2022

Tektite geoarchaeology in mainland Southeast AsiaBen Marwick, Son Thanh Pham, Rachel Brewer, Li-Ying Wang https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/93fpaTektites as chronological markers: after careful geoarchaeological validation only!Recommended by Alain Queffelec and Shanti Pappu based on reviews by Sheila Mishra, Toshihiro Tada, Mike Morley and 1 anonymous reviewer and Shanti Pappu based on reviews by Sheila Mishra, Toshihiro Tada, Mike Morley and 1 anonymous reviewer

Tektites, a naturally occurring glass produced by major cosmic impacts and ejected at long distances, are known from five impacts worldwide [1]. The presence of this impact-generated glass, which can be dated in the same way as a volcanic rock, has been used to date archaeological sites in several regions of the world. This paper by Marwick and colleagues [2] reviews and adds new data on the use and misuse of this specific material as a chronological marker in Australia, East and Southeast Asia, where an impact dated to 0.78 Ma created and widely distributed tektites. This material, found in archaeological excavations in China, Laos, Thaïland, Australia, Borneo, and Vietnam, has been used to date layers containing lithic artifacts, sometimes creating a strong debate about the antiquity of the occupation and lithic production in certain regions. The review of existing data shows that geomorphological data and stratigraphic integrity can be questioned at many sites that have yielded tektites. The new data provided by this paper for five archaeological sites located in Vietnam confirm that many deposits containing tektites are indeed lag deposits and that these artifacts, thus in secondary position, cannot be considered to date the layer. This study also emphasizes the general lack of other dating methods that would allow comparison with the tektite age. In the Vietnamese archaeological sites presented here, discrepancies between methods, and the presence of historical artifacts, confirm that the layers do not share similar age with the cosmic impact that created the tektites. Based on this review and these new results, and following previous propositions [3], Marwick and colleagues conclude that, if tektites can be used as chronological markers, one has to prove that they are in situ. They propose that geomorphological assessment of the archaeological layer as primary deposit must first be attained, in addition to several parameters of the tektites themselves (shape, size distribution, chemical composition). Large error can be made by using only tektites to date an archaeological layer, and this material should not be used solely due to risks of high overestimation of the age of the archaeological production. [1] Rochette, P., Beck, P., Bizzarro, M., Braucher, R., Cornec, J., Debaille, V., Devouard, B., Gattacceca, J., Jourdan, F., Moustard, F., Moynier, F., Nomade, S., Reynard, B. (2021). Impact glasses from Belize represent tektites from the Pleistocene Pantasma impact crater in Nicaragua. Communications Earth & Environment, 2(1), 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00155-1 [2] Marwick, B., Son, P. T., Brewer, R., Wang, L.-Y. (2022). Tektite geoarchaeology in mainland Southeast Asia. SocArXiv, 93fpa, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology, https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/93fpa. [3] Tada, T., Tada, R., Chansom, P., Songtham, W., Carling, P. A., Tajika, E. (2020). In Situ Occurrence of Muong Nong-Type Australasian Tektite Fragments from the Quaternary Deposits near Huai Om, Northeastern Thailand. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science 7(1), 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-020-00378-4 | Tektite geoarchaeology in mainland Southeast Asia | Ben Marwick, Son Thanh Pham, Rachel Brewer, Li-Ying Wang | <p>Tektites formed by an extraterrestrial impact event in Southeast Asia at 0.78 Ma have been found in geological contexts and archaeological sites throughout Australia, East and Southeast Asia. At some archaeological sites, especially in Bose Bas... |  | Asia, Geoarchaeology | Alain Queffelec | 2021-08-14 18:04:18 | View | |

30 Sep 2022

Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF dataBharath Nair, Ismael Rodríguez Palomo, Bo Markussen, Carsten Wiuf, Sarah Fiddyment and Matthew Collins https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.13.483627Assessing glutamine deamination in ancient parchment samplesRecommended by Beatrice Demarchi based on reviews by Maria Codlin and 3 anonymous reviewersData authenticity and approaches to data authentication are crucial issues in ancient protein research. The advent of modern mass spectrometry has enabled the detection of traces of ancient biomolecules contained in fossils, including protein sequences. However, detecting proteins in ancient samples does not equate to demonstrating their endogenous nature: instead, if the mechanisms that drive protein preservation and degradation are understood, then the extent of protein diagenesis can be used for evaluating preservational quality, which in turn may be related to the authenticity of the protein data. The post-mortem deamidation of asparaginyl and glutamyl residues is a key degradation reaction, which can be assessed effectively on the basis of mass spectrometry data, and which has accrued a long history of research, both in terms of describing the mechanisms governing the reactions and with regard to the best strategies for assessing and quantifying the extent of glutamine (Gln) and asparagine (Asn) deamidation in ancient samples (Pal Chowdhury et al., 2019; Ramsøe et al., 2021, 2020; Schroeter and Cleland, 2016; Simpson et al., 2016; Solazzo et al., 2014; Welker et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2012). In their paper, Nair and colleagues (2022) build on this wealth of knowledge and present a tool for quantifying the extent of Gln deamidation in parchment. Parchment is a collagen-based material which can yield extraordinary insights into manuscript manufacturing practices in the past, as well as on the daily lives of the people who assembled and used them (“biocodicology”) (Fiddyment et al., 2021, 2019, 2015; Teasdale et al., 2017). Importantly, the extent of deamidation can be directly related to the quality of the parchment produced: rapid direct deamidation of Gln is induced by the liming process, therefore high extents of deamidation are linked to prolonged exposure to the high pH conditions which are typical of liming, thus implying lower-quality parchment. Nair et al.’s approach focuses on collagen peptides which are typically detected during MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analyses of parchment and build a simple three-step workflow able to yield an overall index of deamidation for a sample (the parchment glutamine index - PQI) 一 taking into account that different Gln residues degrade at different rates according to their micro-chemical environment. The first step involves pre-processing the MALDI spectra, since Nair et al. are specifically interested in maximising information which can be obtained by low-quality data. The second step builds on well-established methods for quantifying Q → E from MALDI-TOF data by modelling the convoluted isotope distributions (Wilson et al., 2012). Once relative rates of deamidation in selected peptides within a given sample are calculated, the third step uses a mixed effects model to combine the individual deamidation estimates and to obtain an overall estimate of the deamidation for a parchment sample (PQI). The PQI can be used effectively for assessing parchment quality, as the authors show for the dataset from Orval Abbey. However, PQI could also have wider applications to the study of processed collagen, which is widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries. In general, the study by Nair et al. is a welcome addition to a growing body of research on protein diagenesis, which will ultimately improve models for the assessment of the authenticity of biomolecular data in archaeology. References Chowdhury, P.M., Wogelius, R., Manning, P.L., Metz, L., Slimak, L., and Buckley, M. 2019. Collagen deamidation in archaeological bone as an assessment for relative decay rates. Archaeometry 61:1382–1398. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12492 Fiddyment, S., Goodison, N.J., Brenner, E., Signorello, S., Price, K., and Collins, M.J.. 2021. Girding the loins? Direct evidence of the use of a medieval parchment birthing girdle from biomolecular analysis. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.202055 Fiddyment,S., Holsinger, B., Ruzzier, C., Devine, A., Binois, A., Albarella, U., Fischer, R., Nichols, E., Curtis, A., Cheese, E., Teasdale, M.D., Checkley-Scott, C., Milner, S.J., Rudy, K.M., Johnson, E.J., Vnouček, J., Garrison, M., McGrory, S., Bradley, D.G., and Collins, M.J. 2015. Animal origin of 13th-century uterine vellum revealed using noninvasive peptide fingerprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:15066–15071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1512264112 Fiddyment, S., Teasdale, M.D., Vnouček, J., Lévêque, É., Binois, A., and Collins, M.J. 2019. So you want to do biocodicology? A field guide to the biological analysis of parchment. Heritage Science 7:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0278-6 Nair, B., Rodríguez Palomo, I., Markussen, B., Wiuf, C., Fiddyment, S., and Collins, M. Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF data. BiorRxiv, 2022.03.13.483627, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.13.483627 Ramsøe, A., Crispin, M., Mackie, M., McGrath, K., Fischer, R., Demarchi, B., Collins, M.J., Hendy, J., and Speller, C. 2021. Assessing the degradation of ancient milk proteins through site-specific deamidation patterns. Sci Rep 11:7795. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87125-x Ramsøe, A., van Heekeren, V., Ponce, P., Fischer, R., Barnes, I., Speller, C., and Collins, M.J. 2020. DeamiDATE 1.0: Site-specific deamidation as a tool to assess authenticity of members of ancient proteomes. J Archaeol Sci 115:105080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2020.105080 Schroeter, E.R., and Cleland, T.P. 2016. Glutamine deamidation: an indicator of antiquity, or preservational quality? Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 30:251–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7445 Simpson, J.P., Penkman, K.E.H., and Demarchi, B. 2016. The effects of demineralisation and sampling point variability on the measurement of glutamine deamidation in type I collagen extracted from bone. J Archaeol Sci 69: 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.002 Solazzo, C., Wilson, J., Dyer, J.M., Clerens, S., Plowman, J.E., von Holstein, I., Walton Rogers, P., Peacock, E.E., and Collins, M.J. 2014. Modeling deamidation in sheep α-keratin peptides and application to archeological wool textiles. Anal Chem 86:567–575. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac4026362 Teasdale, M.D., Fiddyment, S., Vnouček, J., Mattiangeli, V., Speller, C., Binois, A., Carver, M., Dand, C., Newfield, T.P., Webb, C.C., Bradley, D.G., and Collins M.J. 2017. The York Gospels: a 1000-year biological palimpsest. R Soc Open Sci 4:170988. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.170988 Welker, F., Soressi, M.A., Roussel, M., van Riemsdijk, I., Hublin, J.-J., and Collins, M.J. 2016. Variations in glutamine deamidation for a Châtelperronian bone assemblage as measured by peptide mass fingerprinting of collagen. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 3:15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2016.1258825 Wilson, J., van Doorn, N.L., and Collins, M.J. 2012. Assessing the extent of bone degradation using glutamine deamidation in collagen. Anal Chem 84:9041–9048. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac301333t | Parchment Glutamine Index (PQI): A novel method to estimate glutamine deamidation levels in parchment collagen obtained from low-quality MALDI-TOF data | Bharath Nair, Ismael Rodríguez Palomo, Bo Markussen, Carsten Wiuf, Sarah Fiddyment and Matthew Collins | <p style="text-align: justify;">Parchment was used as a writing material in the Middle Ages and was made using animal skins by liming them with Ca(OH)<span class="math-tex">\( _2 \)</span>. During liming, collagen peptides containing Glutamine (Q)... | Bioarchaeology, Europe, Medieval, Zooarchaeology | Beatrice Demarchi | 2022-03-22 12:54:10 | View | ||

19 Jun 2020

Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilitiesCédric Gaucherel and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/wn5zaThe means of complexity in a lithic reduction sequenceRecommended by Marta Arzarello based on reviews by Antony Borel and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Antony Borel and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper entitled “Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities” [1] submitted by C. Gaucherel and C. Noûs represents an interesting reflection about the possibilities to detect the human cognitive abilities in relation to the lithic production. The definition and the study of human cognitive abilities during the Lower Palaeolithic it has always been a complex field of investigation. The relation between the technical skills (lithic production) and the emergence of the linguistic abilities is not easy to investigate due to the difficulty of finding objective data to refer to. The proposition, made by C. Gaucherel and C. Noûs, of a formal grammar of knapping as a method to study the syntactical organisation of the reduction sequences, constitute a new and theoretical useful approach. In order to effectively and precisely define the gestures linked to a specific reduction sequence, for example that of the handaxes shaping, a very large number of variables should be taken into consideration (morphology and quality of the raw material, experience of the knapper, context, percussion technique, forecast of use of the handaxe, etc.). But since a simplification, that brings more elements than the classic one [2,3] is needed, the “action grammar approach” can be a good instrument to detect the common element in a shaping reduction sequence. Furthermore, one of the advantages of the proposed methodology lies in the fact that the definition of the different STs (Stone Technology) can be done according to the technological specific characteristics to be studied and to the type of instrument produced. The deconstruction of knapping sequences could help to detect the degree of complexity of the different steps of the reduction sequences also thanks to the identification of the sub-actions types. The increasing/decreasing of complexity is a very complicate concept in lithic technology. Since at the base of the lithic production there are two basic concepts (angle between the striking platform and the debitage surface - convexity of the debitage/façonnage surface) which are simply declined in an increasingly complex way, it is not easy to define uniquely in what exactly consists the increase in complexity. The approach proposed in the paper “Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities” can help to have new evidences, according to the identification of the required cognitive abilities. The proposed example of formal grammar still needs to be confirmed on archaeological collections, but it is probable that a practical application will allow to further develop the methodology and possibly to highlight additional possibilities of the approach. Bibliography [1] Gaucherel, C. and Noûs C. (2020). Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities. Paleorxiv, wn5za, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/wn5za | Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities | Cédric Gaucherel and Camille Noûs | <p>Recent studies in cognitive neurosciences have postulated a possible link between manual praxis such as tool-making and human languages. If confirmed, such a link opens significant avenues towards the study of the evolution of natural languages... |  | Africa, Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Theoretical archaeology | Marta Arzarello | 2020-04-30 14:18:26 | View | |

14 May 2024

Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methodsChrisowalandis Deligio, Karsten Tolle, David Wigg-Wolf https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8301464A demonstration of the use and finetuning of existing machine learning tools for analysing large complexes of coinsRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The paper outlines the ClaReNet project's exploration of computer-based methods for classifying Celtic coin series, specifically focusing on a hoard from Jersey [1]. They collaborated with Jersey Heritage and numismatists, utilising a large dataset of coin images. The process involves stages such as pre-sorting, size-based sorting, class/type identification, and die studies. They employed IT methods, including object detection and unsupervised learning, followed by supervised learning for data refinement. Collaboration with numismatic experts ensured data quality. The study highlighted challenges in classifying coins, suggesting techniques like image matching alongside convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The results demonstrate the efficacy of semi-automatic processes in coin classification, emphasising the importance of human-computer collaboration for successful outcomes. Overall, this is a good paper, showing how we as archaeologists and numismatics can use existing tools and finetune them for our purposes; without the need for huge domain specific datasets. This research and related papers show how we can more effectively deal with the increasingly bigger data we deal with, saving time on the monotonous and labour intensive tasks, leaving us more time to deal with the big picture. An important strength of the work is the provided public software repository and the dataset. The paper is well written, and a number of images illustrate the methodology as well as the objects used. Reference [1] Deligio, C., Tolle, K., and Wigg-Wolf, D. (2024). Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methods. Zenodo, 8301464, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8301464

| Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methods | Chrisowalandis Deligio, Karsten Tolle, David Wigg-Wolf | <p>In the project "Classifications and Representations for Networks: From types and characteristics to linked open data for Celtic coinages" (ClaReNet) we had access to image data for one of the largest Celtic coin hoards ever found: Le Câtillon I... |  | Computational archaeology | Alex Brandsen | 2023-08-30 15:31:16 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer