Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * ▲ | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Feb 2024

3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, GermanyTharandt, Louise https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7948379Online presentation of the digital reconstruction process of a megalithic tomb : “3Duewelsteene”Recommended by Sophie C. Schmidt and James Allison based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Ronald Visser and Scott Ure based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Ronald Visser and Scott Ure

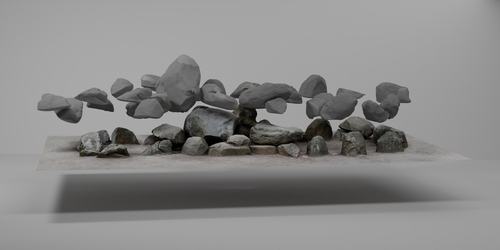

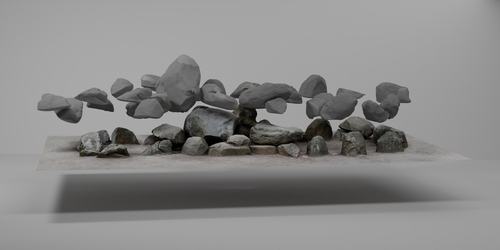

“3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, Germany” (Tharandt 2024) presents several 3-dimensional models of the Düwelsteene monument, along with contextual information about the grave and the process of creating the models. The website (https://3duewelsteene.github.io/) includes English and German versions, making it accessible to a wide audience. The website itself serves as the primary means of presenting the data, rather than as a supplement to a written text. This is an innovative and engaging way to present the research to a wider public. Düwelsteene (“Devil’s Stones”) is a megalithic passage grave from the Funnel Beaker culture, dating to approximately 3300 BC. to 2600 BC. that was excavated in 1932. The website displays three separate 3-dimensional models. They ares shown in the 3D viewer software 3DHOP, which enables viewers to interact with the models in several ways, Annotations on the models display further information. The first model was created by image-based modeling and shows the monument as it appears today. A second model uses historical photographs and excavation data to reconstruct the grave as it appeared prior to the 1932 archaeological excavation. Restoration work following the excavation relocated many of the stones. Pre-1932 photographs collected from residents of the nearby town of Heiden were then used to create a model showing what the tomb looked like before the restoration work. It is commendable that a “certainty view” of the model shows the certainty with which the stones can be put at the reconstructed place. Gaps in the 3D models of stones that were caused by overlap with other stones have been filled with a rough mesh and marked as such, thereby differentiating between known and unknown parts of the stones. The third model is the most imaginative and most interesting. As it shows as the grave as it might have appeared in approximately 3000 B.C., many aspects of this model are necessarily somewhat speculative. There is no direct evidence for exact size and shape of the capstones, the height of the mound, and other details. But enough is known about other similar constructions to allow these details to be inferred with some confidence. Again, care was taken to enable viewers to distinguish between the stones that are still in existence and those that were reconstructed. A video on the home page of the website adds a nice touch. It starts with the model of the Düwelsteene as it currently appears then shows, in reverse order, the changes to the grave, ending with the inferred original state. The 3D reconstructions are convincing and the methods well described. This project follows an open science approach and the FAIR principles, which is commendable and cutting edge in the field of Digital Archaeology. The preprint of the website hosted on zenodo includes all the photos, text, html files, and nine individual 3D model (.ply) files that are combined in the reconstructions exhibited on the website. A “readme.md” file includes details about building the models using CloudCompare and Blender, and modifications to the 3D viewer software (3DHOP) to get the website to improve the display of the reconstructions. We have to note that the link between the reconstructed models and the html page does not work when the files are downloaded from zenodo and opened offline. The html pages open in the browser, and the individual ply files work fine, but the 3D models do not display on the browser page when the html files are opened offline. The online version of the website is working perfectly. The 3Düwelsteene website combines the presentation of archaeological domain knowledge to a lay audience as well as in-depths information on the reconstruction process to make it an interesting contribution for researchers. By providing data and code for the website it also models an Open Science approach, which enables other researchers to re-use these materials. We congratulate the author on a successful reconstruction of the megalithic tomb, an admirable presentation of the archaeological work and the thoughtful outreach to a broad audience. Bibliography | 3Duewelsteene - A website for the 3D visualization of the megalithic passage grave Düwelsteene near Heiden in Westphalia, Germany | Tharandt, Louise | <p>The Düwelsteene near Heiden, Westphalia, is one of the most southern megalithic tombs of the Funnel Beaker culture. In 1932 the Düwelsteene were restored and the appearance of the grave was changed. Even though the megalithic tomb was excavated... |  | Computational archaeology, Mesolithic, Neolithic | Sophie C. Schmidt | 2023-05-21 17:24:22 | View | |

08 Feb 2021

A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, ChinaLuc Doyon, Zhanyang Li, Hua Wang, Lila Geis, Francesco d’Errico https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/68xpzA step towards the challenging recognition of expedient bone toolsRecommended by Camille Daujeard based on reviews by Delphine Vettese, Jarod Hutson and 1 anonymous reviewerThis article by L. Doyon et al. [1] represents an important step to the recognition of bone expedient tools within archaeological faunal assemblages, and therefore deserves publication. In this work, the authors compare bone flakes and splinters experimentally obtained by percussion (hammerstone and anvil technique) with fossil ones coming from the Palaeolithic site of Lingjing in China. Their aim is to find some particularities to help distinguish the fossil bone fragments which were intentionally shaped, from others that result notably from marrow extraction. The presence of numerous (>6) contiguous flake scars and of a continuous size gradient between the lithics and the bone blanks used, appear to be two valuable criteria for identifying 56 bone elements of Lingjing as expedient bone tools. The latter are present alongside other bone tools used as retouchers [2]. Another important point underlined by this study is the co-occurrence of impact and flake scars among the experimentally broken specimens (~90%), while this association is seldom observed on archaeological ones. Thus, according to the authors, a low percentage of that co-occurrence could be also considered as a good indicator of the presence of intentionally shaped bone blanks. About the function of these expedient bone tools, the authors hypothesize that they were used for in situ butchering activities. However, future experimental investigations on this question of the function of these tools are expected, including an experimental use wear program. Finally, highlighting the presence of such a bone industry is of importance for a better understanding of the adaptive capacities and cultural practices of the past hominins. This work therefore invites all taphonomists to pay more attention to flake removal scars on bone elements, keeping in mind the possible existence of that type of bone tools. In fact, being able to distinguish between bone fragments due to marrow recovery and bone tools is still a persistent and important issue for all of us, but one that deserves great caution. [1] Doyon, L., Li, Z., Wang, H., Geis, L. and d'Errico, F. 2021. A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, China. Socarxiv, 68xpz, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/68xpz [2] Doyon, L., Li, Z., Li, H., and d’Errico, F. 2018. Discovery of circa 115,000-year-old bone retouchers at Lingjing, Henan, China. Plos one, 13(3), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194318. | A 115,000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lingjing, Henan, China | Luc Doyon, Zhanyang Li, Hua Wang, Lila Geis, Francesco d’Errico | <p>Activities attested since at least 2.6 Myr, such as stone knapping, marrow extraction, and woodworking may have allowed early hominins to recognize the technological potential of discarded skeletal remains and equipped them with a transferable ... |  | Asia, Middle Palaeolithic, Osseous industry, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Camille Daujeard | 2020-11-01 11:09:13 | View | |

01 Dec 2021

A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-MaatheideSonja Tomasso, Dries Cnuts, Justin Coppe, Marijn Van Gils, Ferdi Geerts, Marc De Bie, Veerle Rots https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pf3smPotential of a large-scale functional analysis to reconstructing past human activities at the Final Palaeolithic site of Lommel-MaatheideRecommended by Marta Arzarello and Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti and Ana Abrunhosa and Alice Leplongeon based on reviews by Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti and Ana Abrunhosa

The paper “A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide” [1] focuses on the final Palaeolithic (Federmesser) site of Lommel-Maatheide. Federmesser sites from northern Belgium such as Lommel-Maatheide, Meer and Rekem, show evidence for dense human occupation of specific areas located on top of Tardiglacial dunes nearby water bodies [2]. Preserved spatial distribution of finds at the sites suggest different activity areas and the presence of habitat structures [2]. However, because of the low organic preservation at the sites, functional analyses of lithic assemblages have the potential to significantly contribute to the spatial organisation of activities at these sites. This study by Tomasso et al. [1], represents an excellent example of a large-scale integrated approach to the study of lithic industries. The article undoubtedly demonstrates the potential of the proposed methodology and the reliability of the results obtained. The article explores two different aspects (linked and excellently interconnected here): the possibility to apply use wear, residue and fracture analyses, on lithic assemblages affected by taphonomical alterations and to study lithic assemblages from dune landscapes. The study allows to answer differentiated questions: what is the influence of taphonomical alterations on use wear analysis? How do excavation methods impact the formation of use wear and the preservation of residues? Can we recognize distinct domestic activities? The article also provides an interesting hypothesis about hunting activities and propulsion methods. The applied methodology is effectively interdisciplinary and innovative. It demonstrates how a truly integrated and articulated approach can represent the turning point for going beyond a mainly descriptive dimension to move towards a real understanding of the sites. Studies dedicated to the analysis of the propulsion mode are not very frequent, but they are surely very important to better understand human behaviour [3]. Here, the methodology developed for the evaluation of the propulsion mode represent an important starting point for the definition of a new approach. Morphological and morphometrical analysis are integrated to the evaluation of the mechanical stress, to fracture delineations and to the hafting system (the latter defined on experimental basis). This article therefore underlines the potential of combining different approaches to functional analysis associated with a ‘tailored’ reference collection and applying them to a high number of artefacts for reconstructing past human activities involving materials that are otherwise not preserved in these contexts. [1] Tomasso, S., Cnuts, D., Coppe, J., Geerts, F., Gils, M.V., Bie, M.D., Rots, V. (2021). A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/pf3sm, ver 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. [2] De Bie, M., Van Gils, M. (2006). Les habitats des groupes à Federmesser (aziliens) dans le Nord de la Belgique. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 103, 781–790. [3] Coppe, J., Lepers, C., Clarenne, V., Delaunois, E., Pirlot, M. and Rots V. (2019). Ballistic Study Tackles Kinetic Energy Values of Palaeolithic Weaponry. Archaeometry, (61)4, 933-956. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12452 | A closer look at an eroded dune landscape: first functional insights into the Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide | Sonja Tomasso, Dries Cnuts, Justin Coppe, Marijn Van Gils, Ferdi Geerts, Marc De Bie, Veerle Rots | <p>The vast Federmessergruppen site of Lommel-Maatheide, which is located in the Campine region (Northern Belgium), revealed the presence of numerous Final Palaeolithic concentrations situated on a large Late Glacial sand ridge on the northern edg... | Environmental archaeology, Landscape archaeology, Lithic technology, Traceology, Upper Palaeolithic | Marta Arzarello | 2021-09-14 17:04:38 | View | ||

28 Feb 2021

A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic AgeAlain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/7dq3b/Open data on beads, pendants, blanks from the Ceramic Age CaribbeanRecommended by Ben Marwick based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang based on reviews by Clarissa Belardelli, Stefano Costa, Robert Bischoff and Li-Ying Wang

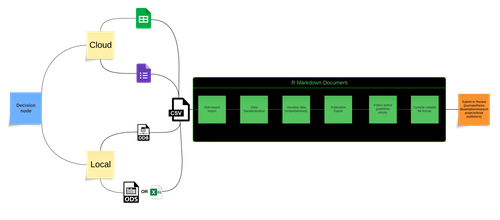

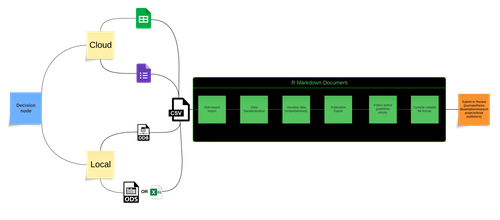

The paper 'A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age' by Queffelec et al. [1] presents a description of a dataset of nearly 5000 lapidary artefacts from over 100 sites. The data are dominated by beads and pendants, which are mostly made from Diorite, Turquoise, Carnelian, Amethyst, and Serpentine. The raw material data is especially valuable as many of these are not locally available on the island. This holds great potential for exchange network analysis. The data may be especially useful for investigating one of the fundamental questions of this region: whether the Cedrosan and Huecan are separate, little related developments, with different origins, or variants or a single tradition [2]. In addition to metric and technological details about the artefacts, the data include a variety of locational details, including coordinates, distance to coast, and altitude. This enables many opportunities for future spatial analysis and geostatistical modelling to understand human behaviours relating to ornament production, use, and discard. I recommend the authors make a minor revision to Table 1 (spatial coverage of the dataset) to make the column with the citations conform to the same citation style used in the rest of the text. I warmly commend the authors for making transparency and reproducibility a priority when preparing their manuscript. Their use of the R Markdown format for writing reproducible, dynamic documents [3] is highly impressive. This is an excellent example for others in the international archaeological science community to follow. The paper is especially useful for researchers who are new to R and R Markdown because of the elegant and accessible way the authors document their research here. [1] Queffelec, A., Fouéré, P. and Caverne, J.-B. 2021. A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age. SocArXiv, 7dq3b, ver. 4 Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/7dq3b [2] Reed, J. A. and Petersen, J. B. 2001. A comparison of Huecan and Cedrosan Saladoid ceramics at the Trants site, Montserrat. In Proceedings of the XVIIIth International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology (pp. 253-267). [3] Marwick, B. 2017. Computational Reproducibility in Archaeological Research: Basic Principles and a Case Study of Their Implementation. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24, 424–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-015-9272-9 | A database of lapidary artifacts in the Caribbean for the Ceramic Age | Alain Queffelec, Pierrick Fouéré, Jean-Baptiste Caverne | <p>Lapidary artifacts show an impressive abundance and diversity during the Ceramic period in the Caribbean islands, especially at the beginning of this period. Most of the raw materials used in this production do not exist naturally on the island... |  | Neolithic, North America, Raw materials, South America, Spatial analysis, Symbolic behaviours | Ben Marwick | 2020-11-13 23:52:34 | View | |

02 Jan 2024

Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenariosDiamanti, Eleni; Yip, Mauhing; Stahl, Annette; Ødegård, Øyvind https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305098Beyond Deep Blue: Underwater robotics, simulations and archaeologyRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Marco Moderato and 1 anonymous reviewerDiamanti et al. (2024) is a significant contribution to the field of underwater robotics and their use in archaeology, with an innovative approach to some major problems in the deployment of said technologies. It identifies issues when it comes to approaching Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) sites and does so through an interest in the combination of data, maneuverability, and the interpretation provided by the instruments that archaeologists operate. The article's motives are clear: it is not enough to find the means to reach these sites, but rather is fundamental to take a step forward in methodology and how we can safeguard certain aspects of data recovery with robust mission planning. To this end, the article does not fail to highlight previous contributions, in an intertwined web of references that demonstrate the marked evolution of the use of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), Remote Operated Vehicles (ROVs), Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Autonomous Surface Vehicles (ASVs), which are growing exponentially in use (see Kapetanović et al. 2020). It should be emphasized that the notion of ‘aquatic environment’ used here is quite broad and is not limited to oceanic or maritime environments, which allows for a larger perspective on distinct technologies that proliferate in underwater archaeology. There is also a relevant discussion on the typologies of sensors and how these autonomous vehicles obtain their data, where are debated Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) and LiDAR systems. Thus, the authors of this article propose the creation of a model that acquires data through simulations, which allows for a better understanding of what a real mission presupposes in the field. Their tripartite method - pre-mission planning; mission plan and post-mission plan - offers a performing algorithm that simplifies and provides reliability to all the parts of the intervention. The use of real cases to create simulation models allows for a substantial approximation to common practice in underwater environments. And yet, the article is at its most innovative status when it combines all the elements it sets out to explore. It could simply focus on the methodological or planning component, on obtaining data, or on theoretical problems. But it goes further, which makes this approach more complete and of interest to the archaeological community. By not taking any part as isolated, the problems and possible solutions arising from the course of the mission are carried over from one parameter to another, where details are worked upon and efficiency goals are set. One of the most significant cases is the tuning of ocean optics in aquatic environments according to the idiosyncracies of real cases (Diamanti et al. 2024: 8), a complex endeavor but absolutely necessary in order to increase the informative potential of the simulation. The exploration of various data capture models is also welcome, for the purposes of comparison and adaptation on a case-by-case basis. The brief theoretical reflection offered at the end of the article dwells in all these points and problematizes the difference between terrestrial and aquatic archaeology. In fact, the distinction does not only exist in the technical component, as although it draws in theoretical elements from archaeology that is carried out on land (see Krieger 2012 for this matter), the problems and interpretations are shaped by different factors and therefore become unique (Diamanti et al 2024: 15). The future, according to the authors, lies in increasing the autonomy of these vehicles so that the human element does not have to make decisions in a systematic way. It is in that note, and in order for that path to become closer to reality, that we strongly recommend this article for publication, in conjunction with the comments of the reviewers. We hope that its integrated approach, which brings together methods, theories and reflections, can become a broader modus operandi within the field of underwater robotics applied to archaeology. References: Diamanti, E., Yip, M., Stahl, A. and Ødegård, Ø. (2024). Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenarios, Zenodo, 8305098, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8305098 Kapetanović, N., Vasilijević, A., Nađ, Đ., Zubčić, K., and Mišković, N. (2020). Marine Robots Mapping the Present and the Past: Unraveling the Secrets of the Deep. Remote Sensing, 12(23), 3902. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/rs12233902 Krieger, W. H. (2012). Theory, Locality, and Methodology in Archaeology: Just Add Water? HOPOS: The Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science, 2(2), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1086/666956

| Advancing data quality of marine archaeological documentation using underwater robotics: from simulation environments to real-world scenarios | Diamanti, Eleni; Yip, Mauhing; Stahl, Annette; Ødegård, Øyvind | <p>This paper presents a novel method for visual-based 3D mapping of underwater cultural heritage sites through marine robotic operations. The proposed methodology addresses the three main stages of an underwater robotic mission, specifically the ... | Computational archaeology, Remote sensing | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-08-31 16:03:10 | View | ||

06 Aug 2023

A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional ProjectScott Madry, Gregory Jansen, Seth Murray, Elizabeth Jones, Lia Willcoxon, Ebtihal Alhashem https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7967035A meticulous description of archiving research data from a long-running landscape research projectRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and Iwona DudekThe paper “A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project” (Madry et al., 2023) describes practices, challenges and opportunities encountered in digital archiving of a landscape research project running in Burgundy, France for more than 45 years. As an unusually long-running multi-disciplinary undertaking working with a large variety of multi-modal digital and non-digital data, the Burgundy project has lived through the development of documentation and archiving technologies from the 1970s until today and faced many of the challenges relating to data management, preservation and migration. The major strenght of the paper is that it provides a detailed description of the evolution of digital data archiving practices in the project including considerations about why some approaches were tested and abandoned. This differs from much of the earlier literature where it has been more common to describe individual solutions how digital archiving was either planned or was performed at one point of time. A longitudinal description of what was planned, how and why it has worked or failed so far, as described in the paper, provides important insights in the everyday hurdles and ways forward in digital archiving. As a description of a digital archiving initiative, the paper makes a valuable contribution for the data archiving scholarship as a case description of practices and considerations in one research project. For anyone working with data management in a research project either as a researcher or data manager, the text provides useful advice on important practical matters to consider ahead, during and after the project. The main advice the authors are giving, is to plan and act for data preservation from the beginning of the project rather than doing it afterwards. To succeed in this, it is crucial to be knowledgeable of the key concepts of data management—such as “digital data fixity, redundant backups, paradata, metadata, and appropriate keywords” as the authors underline—including their rationale and practical implications. The paper shows also that when and if unexpected issues raise, it is important to be open for different alternatives, explore ways forward, and in general be flexible. The paper makes also a timely contribution to the discussion started at the session “Archiving information on archaeological practices and work in the digital environment: workflows, paradata and beyond” at the Computer Applications and Quantitative 2023 conference in Amsterdam where it was first presented. It underlines the importance of understanding and communicating the premises and practices of how data was collected (and made) and used in research for successful digital archiving, and the similar pertinence of documenting digital archiving processes to secure the keeping, preservation and effective reuse of digital archives possible. ReferencesMadry, S., Jansen, G., Murray, S., Jones, E., Willcoxon, L. and Alhashem, E. (2023) A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project, Zenodo, 7967035, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7967035 | A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project | Scott Madry, Gregory Jansen, Seth Murray, Elizabeth Jones, Lia Willcoxon, Ebtihal Alhashem | <p>This paper will consider the practical realities that have been encountered while seeking to create a usable Digital Archiving system of a long-term and multi-participant research project. The lead author has been involved in archaeologic... |  | Computational archaeology, Environmental archaeology, Landscape archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-24 18:46:34 | View | |

11 Dec 2023

A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in EuropeFelix Riede, David N. Matzig, Miguel Biard, Philippe Crombé, Javier Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, Federica Fontana, Daniel Groß, Thomas Hess, Mathieu Langlais, Ludovic Mevel, William Mills, Martin Moník, Nicolas Naudinot, Caroline Posch, Tomas Rimkus, Damian Stefański, Hans Vandendriessche, Shumon T. Hussain https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8195587Questioning Final Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic cultural taxonomy with a data-driven statistical approachRecommended by Anaïs Vignoles based on reviews by Dirk Leder and 2 anonymous reviewersCultural taxonomies are an essential tool for archaeologists working with prehistoric material cultures as they have historically been used to create the basic analytical units for studying cultural evolution through time (de Mortillet, 1883 ; Breuil, 1913). This approach has its limits as the taxonomic units are essentially etic constructions, i.e., they are defined in a cultural context exterior to the one that produced the material culture on which they are based (e.g., Pesesse, 2019). But to approach questions related to cultural evolution, one has to define archaeological units with clear geographic and chronological delineations in order to be compared synchronically and diachronically (e.g., Willey and Philips, 1958). In « A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolitic/Earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe », F. Riede and colleagues propose a novel and interesting approach to question the end of the Palaeolithic and beginning of the Mesolithic’s « named archaeological cultures » (NACs) analytical pertinence (Riede et al., 2023). In this particular context, NACs are indeed very numerous (n = 86) and result from complex and regional research histories. It seems thus pertinent to question the extent to which the said NACs chronological and geographic patterns result from past cultural diversity and evolution, and are not artefacts of research. To do so, the authors adopted a data-driven approach that they describe in detail in the paper. First, they gathered an European data base of lithic tool-kit composition, blade and bladelet technology and armature morphology at 350 key sites considered representative of NACs, dated between 15 and 11 ka (Hussain et al., 2023). These data were then analyzed using geometric morphometrics and a set of statisticaal tests in order to 1) test the coherence of these taxonomic units, and 2) test the chronological change in artefact shape variation. The authors conclude that the data set is partially biased by reasearch practices and histories, as their data-driven approach has only partially replicated traditional NACs for the european Late Palaeolithic/Early Mesolithic. However, their analysis of armature shape evolution has shown a tendency to diversification overtime, a pattern that was already observed in more « traditional » approaches. This study is, in my opinion, an excellent contribution for a significant step in macro-regional approaches to the archaeological record: defining discrete archaeological units that serve as a basis for subsequent analyses aimed at delineating cultural evolutionary processes. The authors propose a carefully designed and statistically grounded procedure in order to achieve these definitions in the most replicable and explicit possible manner. Taking advantage of drawings as a primary source of information is also very original despite several limitations of this approach (such as the necessary selection of most typical artefacts to be represented, the incompleteness of data publication or the difficulty to access all published work across such a large geographic area). The results of the study are convincing enough to allow the authors to discuss the pertinence of European Late Paleo/Early Mesolithic NACs, the potential epistemological and historical factors that could affect this taxonomic framework, as well as to give more weight to the traditional hypothesis of lithic cultural diversification towards the end of the Pleistocene/beginning of the Holocene in Europe. I would also like to underline the authors’ important efforts to ensure transparence and replicability of their study, as well as the accessibility of the data, thanks to extensive supplementary data and a data paper describing their data set in detail. Anaïs L. Vignoles References Breuil, H. (1913). Les subdivisions du paléolithique supérieur et leur signification. In Congrès international d’anthropologie et d’archéologie préhistoriques - compte-rendu de la XIVème session, tome 1:165‑238. Genève: Imprimerie Albert Kündig. Hussain, S. T., Riede, F., Matzig, D. N., Biard, M., Crombé, P., Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, J., Fontana, F., Groß, D., Hess, T., Langlais, M., Mevel, L., Mills, W., Moník, M., Naudinot, N., Posch, C., Rimkus, T., Stefański, D. and Vandendriessche, H. (2023). A Pan-European Dataset Revealing Variability in Lithic Technology, Toolkits, and Artefact Shapes ~15-11 Kya. Scientific Data 10 (1): 593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02500-9. Mortillet, G. (1883). Le Préhistorique, antiquité de l’homme. Reinwald. Paris. Pesesse, D. (2019). Analyser un silex, le façonner à nouveau ? Sur certains usages de la chaîne opératoire au Paléolithique supérieur. Techniques & culture, no 71: 74‑77. https://doi.org/10.4000/tc.11321. Riede, F., Matzig, D. N., Biard, M., Crombé, P., Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, J., Fontana, F., Groß, D., Hess, T., Langlais, M., Mevel, L., Mills, W., Moník, M., Naudinot, N., Posch, C., Rimkus, T., Stefański, D., Vandendriessche, H. and Hussain, S. T. (2023). A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe, Zenodo, 8195587., ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8195587 Willey, G. R. and Phillips, P. (1958). Method and Theory in American Archaeology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. | A meta-analysis of Final Palaeolithic/earliest Mesolithic cultural taxonomy and evolution in Europe | Felix Riede, David N. Matzig, Miguel Biard, Philippe Crombé, Javier Fernández-Lopéz de Pablo, Federica Fontana, Daniel Groß, Thomas Hess, Mathieu Langlais, Ludovic Mevel, William Mills, Martin Moník, Nicolas Naudinot, Caroline Posch, Tomas Rimkus,... | <p>Archaeological systematics, together with spatial and chronological information, are commonly used to infer cultural evolutionary dynamics in the past. For the study of the Palaeolithic, and particularly the European Final Palaeolithic and earl... |  | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Mesolithic, Upper Palaeolithic | Anaïs Vignoles | 2023-07-29 16:06:17 | View | |

04 Jul 2024

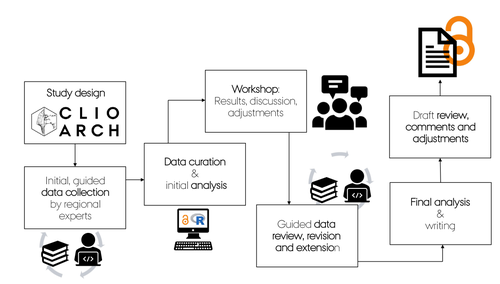

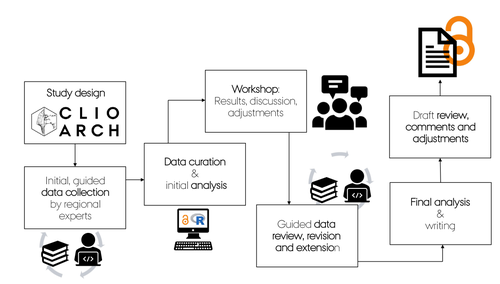

An approach to establishing a workflow pipeline for synergistic analysis of osteological and biochemical data. The case study of Amvrakia in the context of Corinthian colonisation between 625-189 BC in Epirus, Greece.Kiriakos Xanthopoulos, Angeliki Georgiadou, Christina Papageorgopoulou https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298579Establishing a workflow for recording and analysing bioarchaeological dataRecommended by Christianne Fernee based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe paper by Xanthopoulos and colleagues [1] presents an approach to establish a pipeline for the analysis of osteological and biochemical data. This approach integrates novel data collection, FAIR principles for data longevity and accessibility, utilises R markdown and cloud webware. Following the changes recommended by the reviewers this paper presents a welcome contribution to osteoarcheology and bioarchaeology. Osteoarchaeology and bioarchaeology often involves the collection of vast amounts of data both in the field and from consequential analysis in the lab. From this data we can reconstruct many aspects of past human experiences. However, issues often arise when bringing together these diverse types of data. In this regard, this paper proposes are useful methodology in which osteoarchaeological researchers can bring their data together as part of a streamlined process, from data collection to analyses.

References [1] Xanthopoulos, K., Georgiadou, A. and Papageorgopoulou, C. (2024). An approach to establishing a workflow pipeline for synergistic analysis of osteological and biochemical data. The case study of Amvrakia in the context of Corinthian colonisation between 625-189 BC in Epirus, Greece. Zenodo, 11156506, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298579 | An approach to establishing a workflow pipeline for synergistic analysis of osteological and biochemical data. The case study of Amvrakia in the context of Corinthian colonisation between 625-189 BC in Epirus, Greece. | Kiriakos Xanthopoulos, Angeliki Georgiadou, Christina Papageorgopoulou | <p>Bioarchaeology has long focused on understanding past human life through skeletal remains, including oral pathology and stable isotope analysis. Despite advancements in statistical analysis, correlations are still largely made manually. To stre... |  | Antiquity, Bioarchaeology, Computational archaeology, Conservation/Museum studies, Mediterranean, Physical anthropology | Christianne Fernee | 2023-08-30 14:01:44 | View | |

02 Mar 2024

A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasetsNimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733A new approach to Predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer

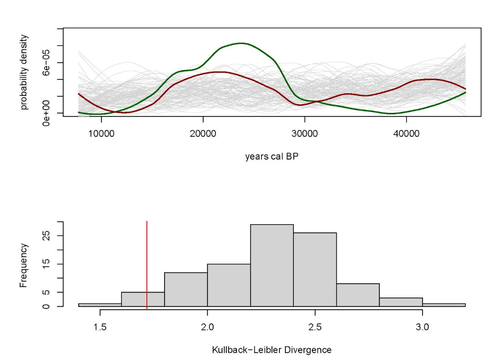

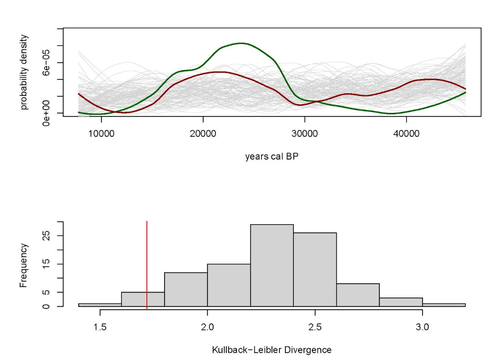

Various biological systems have been subjected to mathematical modelling to enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions among different species. Among these models, the predator-prey model holds a significant position. Its relevance stems not only from its application in biology, where it largely governs the coexistence of diverse species in open ecosystems, but also from its utility in other domains. Predator-prey dynamics have long been a focal point in population ecology, yet access to real-world data is confined to relatively brief periods, typically less than a century. Studying predator-prey dynamics over extended periods presents challenges due to the limited availability of population data spanning more than a century. The most extensive dataset is the hare-lynx records from the Hudson Bay Company, documenting a century of fur trade [1]. However, other records are considerably shorter, usually spanning decades [2,3]. This constraint hampers our capacity to investigate predator-prey interactions over centennial or millennial scales. Marom and Wolkowski [4] propose here that leveraging regional radiocarbon databases offers a solution to this challenge, enabling the reconstruction of predator-prey population dynamics over extensive timeframes. To substantiate this proposition, they draw upon examples from Pleistocene Beringia and the Holocene Judean Desert. This approach is highly relevant and might provide insight into ecological processes occurring at a time scale beyond the limits of current ecological datasets. The methodological approach employed in this article proposes that the summed probability distribution (SPD) of predator radiocarbon dates, which reflects changes in population size, will demonstrate either more or less variation than anticipated from random sampling in a homogeneous distribution spanning the same timeframe. A deviation from randomness would imply a covariation between predator and prey populations. This basic hypothesis makes no assumptions about the frequency, mechanism, or cause of predator-prey interactions, as it is assumed that such aspects cannot be adequately tested with the available data. If validated, this hypothesis would offer initial support for the idea that long-term regional radiocarbon data contain signals of predator-prey interactions. This approach could justify the construction of larger datasets to facilitate a more comprehensive exploration of these signal structures.

References [1] Elton, C. and Nicholson, M., 1942. The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada. J. Anim. Ecol. 11, 215–244. [2] Gilg, O., Sittler, B. and Hanski, I., 2009. Climate change and cyclic predator-prey population dynamics in the high Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01927.x [3] Vucetich, J.A., Hebblewhite, M., Smith, D.W. and Peterson, R.O., 2011. Predicting prey population dynamics from kill rate, predation rate and predator-prey ratios in three wolf-ungulate systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01855.x [4] Marom, N. and Wolkowski, U. (2024). A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets, BioRxiv, 566733, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733 | A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets | Nimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski | <p>Predator-prey interactions have been a central theme in population ecology for the past century, but real-world data sets only exist for recent, relatively short (<100 years) time spans. This limits our ability to study centennial/millennial... |  | Bioarchaeology, Environmental archaeology, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | 2023-12-12 14:37:22 | View | |

28 Feb 2024

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and DutchAlex Brandsen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10610882Multilingual Named Entity Recognition in archaeology: an approach based on deep learningRecommended by Maria Pia di Buono based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Shawn Graham and 2 anonymous reviewers

Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch” (Brandsen 2024) explores the use of BERT-based models for Named Entity Recognition (NER) in archaeology across three languages: English, German, and Dutch. It introduces six models trained and fine-tuned on archaeological literature, followed by the presentation and evaluation of three models specifically tailored for NER tasks. The focus on multilingualism enhances the applicability of the research, while the meticulous evaluation using standard metrics demonstrates a rigorous methodology. The introduction of NER for extracting concepts from literature is intriguing, while the provision of a method for others to contribute to BERT model pre-training enhances collaborative research efforts. The innovative use of BERT models to contextualize archaeological data is a notable strength, bridging the gap between digitized information and computational models. Additionally, the paper's release of fine-tuned models and consideration of environmental implications add further value. In summary, the paper contributes significantly to the task of NER in archaeology, filling a crucial gap and providing foundational tools for data mining and reevaluating legacy archaeological materials and archives. Reference Brandsen, A. (2024). Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch. Zenodo, 8296920, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296920 | Archaeology specific BERT models for English, German, and Dutch | Alex Brandsen | <p>This short paper describes a collection of BERT models for the archaeology domain. We took existing language specific BERT models in English, German, and Dutch, and further pre-trained them with archaeology specific training data. We then took ... |  | Computational archaeology | Maria Pia di Buono | 2023-08-29 14:50:21 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer