Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 Oct 2023

From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editionsAuth. Frederic; Rösler, Katja; Domscheit, Wenke; Hofmann, Kerstin P. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7304578Revitalising archaeological corpus publications through digitisation – the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae as exemplary casesRecommended by Felix Riede, Sébastien Plutniak and Shumon Tobias Hussain and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova

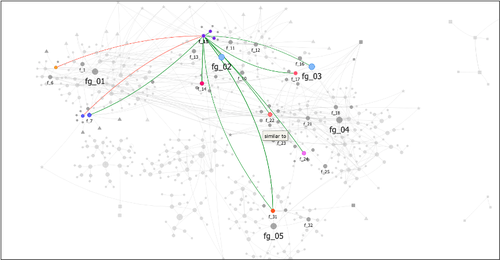

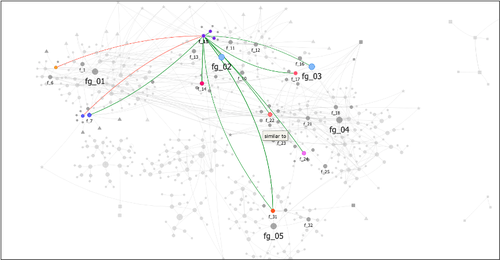

The paper entitled “From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions” submitted by Frederic Auth and colleagues discusses how those rich and often meticulously illustrated catalogues of particular find classes that exist in many corners of archaeology can be brought to the cutting edge of contemporary research through digitisation. This paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology, taxonomy, classification theory, and computational approaches in archaeology. Auth et al. (2023) begin with outlining the useful notion of the ‘thing-edition’ originally coined by Kerstin Hofmann in the context of her work with the many massive corpora of finds that have characterised, in particular, earlier archaeological knowledge production in Germany (Hofmann et al. 2019; Hofmann 2018). This work critically examines changing trends in the typological characterisation and recording of various find categories, their theoretical foundations or lack thereof and their legacy on contemporary practice. The present contribution focuses on what happens with such corpora when they are integrated into digitisation projects, specifically the efforts by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), the so-called iDAI.world and in regard to two Roman-era material culture groups, the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum (Roman finds from beyond the empire’s borders in eight printed volumes covering thousands of finds of various categories), and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae (Roman plain ware). Drawing on Bruno Latour’s (2005) actor-network theory (ANT), Auth et al. discuss and reflect on the challenges met and choices to be made when thing-editions are to be transformed into readily accessible data, that is as linked to open, usable data. The intellectual and infrastructural workload involved in such digitisation projects is not to be underestimated. Here, the contribution by Auth et al. excels in the manner that it does not present the finished product – the fully digitised corpora – but instead offers a glimpse ‘under the hood’ of the digitisation process as an interaction between analogue corpus, research team, and the technologies at hand. These aspects were rarely addressed in the literature, rooted in the 1970s early work (Borillo and Gardin 1974; Gaines 1981), on archaeological computerised databases, focused on technical dimensions (see Rösler 2016 for an exception). Their paper can so also be read in the broader context of heterogeneous computer-assisted knowledge ecologies and ‘mangles of practice’ (see Pickering and Guzik 2009) in which practitioners and technological structures respond to each other’s needs and attempt to cooperate in creative ways. As such, Auth et al.’s considerations not least offer valuable resources for Science and Technology Studies-inspired discussions on the cross-fertilization of archaeological theory, practice and currently emerging material and virtual research infrastructures and can be read in conjunction to Gavin Lucas’ (2022) paper on ‘machine epistemology’ due to appear in the same volume. Perhaps more importantly, however, the work by Auth and colleagues (2023) exemplifies the due diligence required in not merely turning a catalogue from paper to digital document but in transforming such catalogues into long-lasting and patently usable repositories of generations of scholars to come. Deploying the Latourian notions of trade-off and recursive reference, Auth et al. first examine the structure, strengths, and weakness of the two corpora before moving on to showing how the freshly digitised versions offer new and alternative ways of analysing the archaeological material at hand, notably through immediate visualisation opportunities, through ceramic form combinations, and relational network diagrams based on the data inherent in the respective thing-editions. Catalogues including basic descriptions and artefact illustrations exist for most if not all archaeological periods. They constitute an essential backbone of archaeological work as repeated access to primary material is impractical if not impossible. The catalogues addressed by Auth et al. themselves reflect major efforts on behalf of archaeological experts to arrive at clear and operational classifications in a pre-computerised era. The continued and expanded efforts by Auth and colleagues build on these works and clearly demonstrate the enormous analytical potential to make such data not merely more accessible but also more flexibly interoperable. Their paper will therefore be an important reference for future work with similar ambitions facing similar challenges. References Auth, Frederic, Katja Rösler, Wenke Domscheit, and Kerstin P. Hofmann. 2023. “From Paper to Byte: A Workshop Report on the Digital Transformation of Two Thing Editions.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8214563 Borillo, Mario, and Jean-Claude Gardin. 1974. Les Banques de Données Archéologiques. Marseille: Éditions du CNRS. Gaines, Sylvia W., ed. 1981. Data Bank Applications in Archaeology. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. Hofmann, Kerstin P. 2018. “Dingidentitäten Und Objekttransformationen. Einige Überlegungen Zur Edition von Archäologischen Funden.” In Objektepistemologien. Zum Verhältnis von Dingen Und Wissen, edited by Markus Hilgert, Kerstin P. Hofmann, and Henrike Simon, 179–215. Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 59. Berlin: Edition Topoi. https://dx.doi.org/10.17171/3-59 Hofmann, Kerstin P., Susanne Grunwald, Franziska Lang, Ulrike Peter, Katja Rösler, Louise Rokohl, Stefan Schreiber, Karsten Tolle, and David Wigg-Wolf. 2019. “Ding-Editionen. Vom Archäologischen (Be-)Fund Übers Corpus Ins Netz.” E-Forschungsberichte des DAI 2019/2. E-Forschungsberichte Des DAI. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2236/6674 Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lucas, Gavin. 2022. “Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7622162 Pickering, Andrew, and Keith Guzik, eds. 2009. The Mangle in Practice: Science, Society, and Becoming. The Mangle in Practice. Science and Cultural Theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Rösler, Katja. 2016. “Mit Den Dingen Rechnen: ‚Kulturen‘-Forschung Und Ihr Geselle Computer.” In Massendinghaltung in Der Archäologie. Der Material Turn Und Die Ur- Und Frühgeschichte, edited by Kerstin P. Hofmann, Thomas Meier, Doreen Mölders, and Stefan Schreiber, 93–110. Leiden: Sidestone Press. | From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions | Auth. Frederic; Rösler, Katja; Domscheit, Wenke; Hofmann, Kerstin P. | <p>One specific form of publication for archaeological objects are catalogues, atlases and corpora. Kerstin Hofmann has introduced the term ‘Ding-Editionen’ (thing editions) for this category of publications that present their data in lists, short... |  | Antiquity, Computational archaeology, Dating, Theoretical archaeology | Felix Riede | 2022-11-08 16:00:49 | View | |

02 Nov 2020

Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case StudyJoseph Lewis https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/mxas2A probabilistic method for Least Cost Path calculation.Recommended by Otis Crandell based on reviews by Georges Abou Diwan and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper entitled “Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study” [1] submitted by J. Lewis presents an innovative approach to applying Least Cost Path (LCP) analysis to incorporate uncertainty of the Digital Elevation Model used as the topographic surface on which the path is calculated. The proposition of using Monte Carlo simulations to produce numerous LCP, each with a slightly different DEM included in the error range of the model, allows one to strengthen the method by proposing a probabilistic LCP rather than a single and arbitrary one which does not take into account the uncertainty of the topographic reconstruction. This new method is integrated in the R package leastcostpath [2]. The author tests the method using a Roman road built along a ridge in Cumbria, England. The integration of the uncertainty of the DEM, thanks to Monte Carlo simulations, shows that two paths could have the same probability to be the real LCP. One of them is indeed the path that the Roman road took. In particular, it is one of two possibilities of LCP in the south to north direction. This new probabilistic method therefore strengthens the reconstruction of past pathways, while also allowing new hypotheses to be tested, and, in this case study, to suggest that the northern part of the Roman road’s location was selected to help the northward movements. [1] Lewis, J., 2020. Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study. SocArXiv, mxas2, ver 17 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology, 10.31235/osf.io/mxas2. [2] Lewis, J., 2020. leastcostpath: Modelling Pathways and Movement Potential Within a Landscape. R package. Version 1.7.4. | Probabilistic Modelling using Monte Carlo Simulation for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: a Roman Road Case Study | Joseph Lewis | <p>The movement of past peoples in the landscape has been studied extensively through the use of Least Cost Path (LCP) analysis. Although methodological issues of applying LCP analysis in Archaeology have frequently been discussed, the effect of v... |  | Spatial analysis | Otis Crandell | Adam Green, Georges Abou Diwan | 2020-08-05 12:10:46 | View |

26 Oct 2022

Technological analysis and experimental reproduction of the techniques of perforation of quartz beads from the Ceramic period in the AntillesMadeleine Raymond, Pierrick Fouéré, Ronan Ledevin, Yannick Lefrais and Alain Queffelec https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/a5tgpUsing Cactus Thorns to Drill Quartz: A Proof of ConceptRecommended by Donatella Usai and Jonathan Hanna based on reviews by Viola Stefano, ? and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Viola Stefano, ? and 1 anonymous reviewer

Quartz adornments (beads, pendants, etc.) are frequent artifacts found in the Caribbean, particularly from Early Ceramic Age contexts (~500 BC-AD 700). As a form of specialization, these are sometimes seen as indicative of greater social complexity and craftsmanship during this time. Indeed, ethnographic analogy has purported that such stone adornments require enormous inputs of time and labor, as well as some technological sophistication with tools hard-enough to create the holes (e.g., metal or diamonds). However, given these limitations, one would expect unfinished beads to be a common artifact in the archaeological record. Yet, whereas unworked/raw materials are often found, beads with partial/unfinished perforations are not. References:

| Technological analysis and experimental reproduction of the techniques of perforation of quartz beads from the Ceramic period in the Antilles | Madeleine Raymond, Pierrick Fouéré, Ronan Ledevin, Yannick Lefrais and Alain Queffelec | <p style="text-align: justify;">Personal ornaments are a very specific kind of material production in human societies and are particularly valuable artifacts for the archaeologist seeking to understand past societies. In the Caribbean, Early Ceram... |  | Lithic technology, Neolithic, South America, Symbolic behaviours, Traceology | Donatella Usai | 2022-09-06 14:01:51 | View | |

19 Jun 2020

Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilitiesCédric Gaucherel and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/wn5zaThe means of complexity in a lithic reduction sequenceRecommended by Marta Arzarello based on reviews by Antony Borel and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Antony Borel and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper entitled “Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities” [1] submitted by C. Gaucherel and C. Noûs represents an interesting reflection about the possibilities to detect the human cognitive abilities in relation to the lithic production. The definition and the study of human cognitive abilities during the Lower Palaeolithic it has always been a complex field of investigation. The relation between the technical skills (lithic production) and the emergence of the linguistic abilities is not easy to investigate due to the difficulty of finding objective data to refer to. The proposition, made by C. Gaucherel and C. Noûs, of a formal grammar of knapping as a method to study the syntactical organisation of the reduction sequences, constitute a new and theoretical useful approach. In order to effectively and precisely define the gestures linked to a specific reduction sequence, for example that of the handaxes shaping, a very large number of variables should be taken into consideration (morphology and quality of the raw material, experience of the knapper, context, percussion technique, forecast of use of the handaxe, etc.). But since a simplification, that brings more elements than the classic one [2,3] is needed, the “action grammar approach” can be a good instrument to detect the common element in a shaping reduction sequence. Furthermore, one of the advantages of the proposed methodology lies in the fact that the definition of the different STs (Stone Technology) can be done according to the technological specific characteristics to be studied and to the type of instrument produced. The deconstruction of knapping sequences could help to detect the degree of complexity of the different steps of the reduction sequences also thanks to the identification of the sub-actions types. The increasing/decreasing of complexity is a very complicate concept in lithic technology. Since at the base of the lithic production there are two basic concepts (angle between the striking platform and the debitage surface - convexity of the debitage/façonnage surface) which are simply declined in an increasingly complex way, it is not easy to define uniquely in what exactly consists the increase in complexity. The approach proposed in the paper “Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities” can help to have new evidences, according to the identification of the required cognitive abilities. The proposed example of formal grammar still needs to be confirmed on archaeological collections, but it is probable that a practical application will allow to further develop the methodology and possibly to highlight additional possibilities of the approach. Bibliography [1] Gaucherel, C. and Noûs C. (2020). Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities. Paleorxiv, wn5za, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/wn5za | Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities | Cédric Gaucherel and Camille Noûs | <p>Recent studies in cognitive neurosciences have postulated a possible link between manual praxis such as tool-making and human languages. If confirmed, such a link opens significant avenues towards the study of the evolution of natural languages... |  | Africa, Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Theoretical archaeology | Marta Arzarello | 2020-04-30 14:18:26 | View | |

06 Aug 2023

A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional ProjectScott Madry, Gregory Jansen, Seth Murray, Elizabeth Jones, Lia Willcoxon, Ebtihal Alhashem https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7967035A meticulous description of archiving research data from a long-running landscape research projectRecommended by Isto Huvila based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann and Iwona DudekThe paper “A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project” (Madry et al., 2023) describes practices, challenges and opportunities encountered in digital archiving of a landscape research project running in Burgundy, France for more than 45 years. As an unusually long-running multi-disciplinary undertaking working with a large variety of multi-modal digital and non-digital data, the Burgundy project has lived through the development of documentation and archiving technologies from the 1970s until today and faced many of the challenges relating to data management, preservation and migration. The major strenght of the paper is that it provides a detailed description of the evolution of digital data archiving practices in the project including considerations about why some approaches were tested and abandoned. This differs from much of the earlier literature where it has been more common to describe individual solutions how digital archiving was either planned or was performed at one point of time. A longitudinal description of what was planned, how and why it has worked or failed so far, as described in the paper, provides important insights in the everyday hurdles and ways forward in digital archiving. As a description of a digital archiving initiative, the paper makes a valuable contribution for the data archiving scholarship as a case description of practices and considerations in one research project. For anyone working with data management in a research project either as a researcher or data manager, the text provides useful advice on important practical matters to consider ahead, during and after the project. The main advice the authors are giving, is to plan and act for data preservation from the beginning of the project rather than doing it afterwards. To succeed in this, it is crucial to be knowledgeable of the key concepts of data management—such as “digital data fixity, redundant backups, paradata, metadata, and appropriate keywords” as the authors underline—including their rationale and practical implications. The paper shows also that when and if unexpected issues raise, it is important to be open for different alternatives, explore ways forward, and in general be flexible. The paper makes also a timely contribution to the discussion started at the session “Archiving information on archaeological practices and work in the digital environment: workflows, paradata and beyond” at the Computer Applications and Quantitative 2023 conference in Amsterdam where it was first presented. It underlines the importance of understanding and communicating the premises and practices of how data was collected (and made) and used in research for successful digital archiving, and the similar pertinence of documenting digital archiving processes to secure the keeping, preservation and effective reuse of digital archives possible. ReferencesMadry, S., Jansen, G., Murray, S., Jones, E., Willcoxon, L. and Alhashem, E. (2023) A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project, Zenodo, 7967035, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7967035 | A Focus on the Future of our Tiny Piece of the Past: Digital Archiving of a Long-term Multi-participant Regional Project | Scott Madry, Gregory Jansen, Seth Murray, Elizabeth Jones, Lia Willcoxon, Ebtihal Alhashem | <p>This paper will consider the practical realities that have been encountered while seeking to create a usable Digital Archiving system of a long-term and multi-participant research project. The lead author has been involved in archaeologic... |  | Computational archaeology, Environmental archaeology, Landscape archaeology | Isto Huvila | 2023-05-24 18:46:34 | View | |

01 Sep 2023

Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854))Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552A zooarchaeological perspective on testudine bones from Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Southeast AsiaRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta based on reviews by Noel Amano and Iratxe Boneta

The study of the evolution of the human diet has been a central theme in numerous archaeological and paleoanthropological investigations. By reconstructing diets, researchers gain deeper insights into how humans adapted to their environments. The analysis of animal bones plays a crucial role in extracting dietary information. Most studies involving ancient diets rely heavily on zooarchaeological examinations, which, due to their extensive history, have amassed a wealth of data. During the Pleistocene–Holocene periods, testudine bones have been commonly found in a multitude of sites. The use of turtles and tortoises as food sources appears to stretch back to the Early Pleistocene [1-4]. More importantly, these small animals play a more significant role within a broader debate. The exploitation of tortoises in the Mediterranean Basin has been examined through the lens of optimal foraging theory and diet breadth models (e.g. [5-10]). According to the diet breadth model, resources are incorporated into diets based on their ranking and influenced by factors such as net return, which in turn depends on caloric value and search/handling costs [11]. Within these theoretical frameworks, tortoises hold a significant position. Their small size and sluggish movement require minimal effort and relatively simple technology for procurement and processing. This aligns with optimal foraging models in which the low handling costs of slow-moving prey compensate for their small size [5-6,9]. Tortoises also offer distinct advantages. They can be easily transported and kept alive, thereby maintaining freshness for deferred consumption [12-14]. For example, historical accounts suggest that Mexican traders recognised tortoises as portable and storable sources of protein and water [15]. Furthermore, tortoises provide non-edible resources, such as shells, which can serve as containers. This possibility has been discussed in the context of Kebara Cave [16] and noted in ethnographic and historical records (e.g. [12]). However, despite these advantages, their slow growth rate might have rendered intensive long-term predation unsustainable. While tortoises are well-documented in the Southeast Asian archaeological record, zooarchaeological analyses in this region have been limited, particularly concerning prehistoric hunter-gatherer populations that may have relied extensively on inland chelonian taxa. With the present paper Bochaton et al. [17] aim to bridge this gap by conducting an exhaustive zooarchaeological analysis of turtle bone specimens from four Hoabinhian hunter-gatherer archaeological assemblages in Thailand and Cambodia. These assemblages span from the Late Pleistocene to the first half of the Holocene. The authors focus on bones attributed to the yellow-headed tortoise (Indotestudo elongata), which is the most prevalent taxon in the assemblages. The research include osteometric equations to estimate carapace size and explore population structures across various sites. The objective is to uncover human tortoise exploitation strategies in the region, and the results reveal consistent subsistence behaviours across diverse locations, even amidst varying environmental conditions. These final proposals suggest the possibility of cultural similarities across different periods and regions in continental Southeast Asia. In summary, this paper [17] represents a significant advancement in the realm of zooarchaeological investigations of small prey within prehistoric communities in the region. While certain approaches and issues may require further refinement, they serve as a comprehensive and commendable foundation for assessing human hunting adaptations.

References [1] Hartman, G., 2004. Long-term continuity of a freshwater turtle (Mauremys caspica rivulata) population in the northern Jordan Valley and its paleoenvironmental implications. In: Goren-Inbar, N., Speth, J.D. (Eds.), Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 61-74. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dtct.11 [2] Alperson-Afil, N., Sharon, G., Kislev, M., Melamed, Y., Zohar, I., Ashkenazi, R., Biton, R., Werker, E., Hartman, G., Feibel, C., Goren-Inbar, N., 2009. Spatial organization of hominin activities at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. Science 326, 1677-1680. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180695 [3] Archer, W., Braun, D.R., Harris, J.W., McCoy, J.T., Richmond, B.G., 2014. Early Pleistocene aquatic resource use in the Turkana Basin. J. Hum. Evol. 77, 74-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.02.012 [4] Blasco, R., Blain, H.A., Rosell, J., Carlos, D.J., Huguet, R., Rodríguez, J., Arsuaga, J.L., Bermúdez de Castro, J.M., Carbonell, E., 2011. Earliest evidence for human consumption of tortoises in the European Early Pleistocene from Sima del Elefante, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain. J. Hum. Evol. 11, 265-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.06.002 [5] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N., Surovell, T.A., Tchernov, E., Bar-Yosef, O., 1999. Palaeolithic growth pulses evidenced by small animal exploitation. Science 283, 190-194. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5399.190 [6] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., Surovell, T.A., 2000. The tortoise and the hare: small-game use, the Broad-Spectrum Revolution, and paleolithic demography. Curr. Anthropol. 41, 39-73. https://doi.org/10.1086/300102 [7] Stiner, M.C., 2001. Thirty years on the “Broad Spectrum Revolution” and paleolithic demography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 (13), 6993-6996. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.121176198 [8] Stiner, M.C., 2005. The Faunas of Hayonim Cave (Israel): a 200,000-Year Record of Paleolithic Diet. Demography and Society. American School of Prehistoric Research, Bulletin 48. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge. [9] Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D., 2002. Approaches to prehistoric diet breadth, demography, and prey ranking systems in time and space. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 9, 181-214. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016530308865 [10] Blasco, R., Cochard, D., Colonese, A.C., Laroulandie, V., Meier, J., Morin, E., Rufà, A., Tassoni, L., Thompson, J.C. 2022. Small animal use by Neanderthals. In Romagnoli, F., Rivals, F., Benazzi, S. (eds.), Updating Neanderthals: Understanding Behavioral Complexity in the Late Middle Palaeolithic. Elsevier Academic Press, pp. 123-143. ISBN 978-0-12-821428-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2019-0-03240-2 [11] Winterhalder, B., Smith, E.A., 2000. Analyzing adaptive strategies: human behavioural ecology at twenty-five. Evol. Anthropol. 9, 51-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(2000)9:2%3C51::aid-evan1%3E3.0.co;2-7 [12] Schneider, J.S., Everson, G.D., 1989. The Desert Tortoise (Xerobates agassizii) in the Prehistory of the Southwestern Great Basin and Adjacent areas. J. Calif. Gt. Basin Anthropol. 11, 175-202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825383 [13] Thompson, J.C., Henshilwood, C.S., 2014b. Nutritional values of tortoises relative to ungulates from the Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa: implications for foraging and social behaviour. J. Hum. Evol. 67, 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.010 [14] Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Smith, K.T., Maul, L.Ch., Sañudo, P., Barkai, R., Gopher, A. 2016. Tortoises as a Dietary Supplement: a view from the Middle Pleistocene site of Qesem Cave, Israel. Quat Sci Rev 133, 165-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.12.006 [15] Pepper, C., 1963. The truth about the tortoise. Desert Mag. 26, 10-11. [16] Speth, J.D., Tchernov, E., 2002. Middle Paleolithic tortoise use at Kebara Cave (Israel). J. Archaeol. Sci. 29, 471-483. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2001.0740 [17] Bochaton, C., Chantasri, S., Maneechote, M., Claude, J., Griggo, C., Naksri, W., Forestier, H., Sophady, H., Auertrakulvit, P., Bowonsachoti, J. and Zeitoun, V. (2023) Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed Tortoise (Indotestudo elongata (Blyth, 1854)), BioRXiv, 2023.04.27.538552 , ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538552v3 | Zooarchaeological investigation of the Hoabinhian exploitation of reptiles and amphibians in Thailand and Cambodia with a focus on the Yellow-headed tortoise (*Indotestudo elongata* (Blyth, 1854)) | Corentin Bochaton, Sirikanya Chantasri, Melada Maneechote, Julien Claude, Christophe Griggo, Wilailuck Naksri, Hubert Forestier, Heng Sophady, Prasit Auertrakulvit, Jutinach Bowonsachoti, Valery Zeitoun | <p style="text-align: justify;">While non-marine turtles are almost ubiquitous in the archaeological record of Southeast Asia, their zooarchaeological examination has been inadequately pursued within this tropical region. This gap in research hind... |  | Asia, Taphonomy, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | Iratxe Boneta, Noel Amano | 2023-05-02 09:30:50 | View |

26 Mar 2024

What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery.Philippe Boissinot https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433Abstract and Concrete – Querying the Metaphysics and Geometry of Pottery ClassificationRecommended by Shumon Tobias Hussain , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak , Felix Riede and Sébastien Plutniak based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

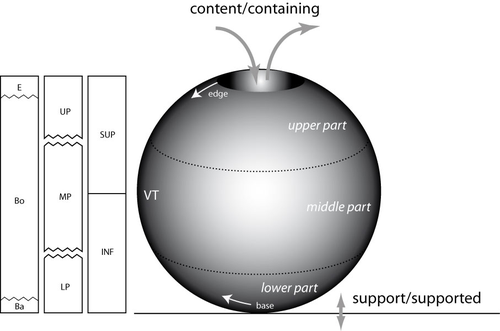

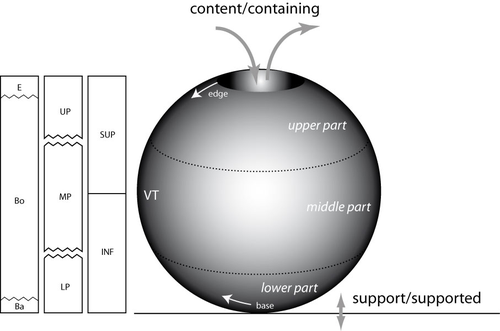

“What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery” by P. Boissinot (1) is a timely contribution to broader theoretical reflections on classification and ordering practices in archaeology, including type-construction and justification. Boissinot rightly reminds us that engagement with the type concept always touches upon the uneasy relationship between the abstract and the concrete, alternatively cast as the ongoing struggle in knowledge production between idealization and particularization. Types are always abstract and as such both ‘more’ and ‘less’ than the concrete objects they refer to. They are ‘more’ because they establish a higher-order identity of variously heterogeneous, concrete objects and they are ‘less’ because they necessarily reduce the richness of the concrete and often erase it altogether. The confusion that types evoke in archaeology and elsewhere has therefore a lot to do with the fact that types are simply not spatiotemporally distinct particulars. As abstract entities, types so almost automatically re-introduce the question of universalism but they do not decide this question, and Boissinot also tentatively rejects such ambitions. In fact, with Boissinot (1) it may be said that universality is often precisely confused with idealization, which is indispensable to all archaeological ordering practices. Idealization, increasingly recognized as an important epistemic operation in science (2, 3), paradoxically revolves around the deliberate misrepresentation of the empirical systems being studied, with models being the paradigm cases (4). Models can go so far as to assume something strictly false about the phenomena under consideration in order to advance their epistemic goals. In the words of Angela Potochnik (5), ‘the role of idealization in securing understanding distances understanding from truth but […] this understanding nonetheless gives rise to scientific knowledge’. The affinity especially to models may in part explain why types are so controversial and are often outright rejected as ‘real’ or ‘useful’ by those who only recognize the existence of concrete particulars (nominalism). As confederates of the abstract, types thus join the ranks of mathematics and geometry, which the author identifies as prototypical abstract systems. Definitions are also abstract. According to Boissinot (1), they delineate a ‘position of limits’, and the precision and rigorousness they bring comes at the cost of subjectivity. This unites definitions and types, as both can be precise and clear-cut but they can never be strictly singular or without alternative – in order to do so, they must rely on yet another higher-order system of external standards, and so ad infinitum. Boissinot (1) advocates a mathematical and thus by definition abstract approach to archaeological type-thinking in the realm of pottery, as the abstractness of this approach affords relatively rigorous description based on the rules of geometry. Importantly, this choice is not a mysterious a priori rooted in questionable ideas about the supposed superiority of such an approach but rather is the consequence of a careful theoretical exploration of the particularities (domain-specificities) of pottery as a category of human practice and materiality. The abstract thus meets the concrete again: objects of pottery, in sharp contrast to stone artefacts for example, are the product of additive processes. These processes, moreover, depend on the ‘fusion’ of plastic materials and the subsequent fixation of the resulting configuration through firing (processes which, strictly speaking, remove material, such as stretching, appear to be secondary vis-à-vis global shape properties). Because of this overriding ‘fusion’ of pottery, the identification of parts, functional or otherwise, is always problematic and indeterminate to some extent. As products of fusion, parts and wholes represent an integrated unity, and this distinguishes pottery from other technologies, especially machines. The consequence is that the presence or absence of parts and their measurements may not be a privileged locus of type-construction as they are in some biological contexts for example. The identity of pottery objects is then generally bound to their fusion. As a ‘plastic montage’ rather than an assembly of parts, individual parts cannot simply be replaced without threatening the identity of the whole. Although pottery can and must sometimes be repaired, this renders its objects broadly morpho-static (‘restricted plasticity’) rather than morpho-dynamic, which is a condition proper to other material objects such as lithic (use and reworking) and metal artefacts (deformation) but plays out in different ways there. This has a number of important implications, namely that general shape and form properties may be expected to hold much more relevant information than in technological contexts characterized by basal modularity or morpho-dynamics. It is no coincidence that ‘fusion’ is also emphasized by Stephen C. Pepper (6) as a key category of what he calls contextualism. Fusion for Pepper pays dividends to the interpenetration of different parts and relations, and points to a quality of wholes which cannot be reduced any further and integrates the details into a ‘more’. Pepper maintains that ‘fusion, in other words, is an agency of simplification and organization’ – it is the ‘ultimate cosmic determinator of a unit’ (p. 243-244, emphasis added). This provides metaphysical reasons to look at pottery from a whole-centric perspective and to foreground the agency of its materiality. This is precisely what Boissinot (1) does when he, inspired by the great techno-anthropologist François Sigaut (7), gestures towards the fact that elementarily a pot is ‘useful for containing’. He thereby draws attention not to the function of pottery objects but to what pottery as material objects do by means of their material agency: they disclose a purposive tension between content and container, the carrier and carried as well as inclusion and exclusion, which can also be understood as material ‘forces’ exerted upon whatever is to be contained. This, and not an emic reading of past pottery use, leads to basic qualitative distinctions between open and closed vessels following Anna O. Shepard’s (8) three basic pottery categories: unrestricted, restricted, and necked openings. These distinctions are not merely intuitive but attest to the object-specificity of pottery as fused matter. This fused dimension of pottery also leads to a recognition that shapes have geometric properties that emerge from the forced fusion of the plastic material worked, and Boissinot (1) suggests that curvature is the most prominent of such features, which can therefore be used to describe ‘pure’ pottery forms and compare abstract within-pottery differences. A careful mathematical theorization of curvature in the context of pottery technology, following George D. Birkhoff (9), in this way allows to formally distinguish four types of ‘geometric curves’ whose configuration may serve as a basis for archaeological object grouping. The idealization involved in this proposal is not accidental but deliberately instrumental – it reminds us that type-thinking in archaeology cannot escape the abstract. It is notable here that the author does not suggest to simply subject total pottery form to some sort of geometric-morphometric analysis but develops a proposal that foregrounds a limited range of whole-based geometric properties (in contrast to part-based) anchored in general considerations as to the material specificity of pottery as quasi-species of objects. As Boissinot (1) notes himself, this amounts to a ‘naturalization’ of archaeological artefacts and offers somewhat of an alternative (a third way) to the old discussion between disinterested form analysis and functional (and thus often theory-dependent) artefact groupings. He thereby effectively rejects both of these classic positions because the first ignores the particularities of pottery and the real function of artefacts is in most cases archaeologically inaccessible. In this way, some clear distance is established to both ethnoarchaeology and thing studies as a project. Attending to the ‘discipline of things’ proposal by Bjørnar Olsen and others (10, 11), and by drawing on his earlier work (12), Boissinot interestingly notes that archaeology – never dealing with ‘complete societies’ – could only be ‘deficient’. This has mainly to do with the underdetermination of object function by the archaeological record (and the confusion between function and functionality) as outlined by the author. It seems crucial in this context that Boissinot does not simply query ‘What is a thing?’ as other thing-theorists have previously done, but emphatically turns this question into ‘In what way is it not the same as something else?’. He here of course comes close to Olsen’s In Defense of Things insofar as the ‘mode of being’ or the ‘ontology’ of things is centred. What appears different, however, is the emphasis on plurality and within-thing heterogeneity on the level of abstract wholes. With Boissinot, we always have to speak of ontologies and modes of being and those are linked to different kinds of things and their material specificities. Theorizing and idealizing these specificities are considered central tasks and goals of archaeological classification and typology. As such, this position provides an interesting alternative to computational big-data (the-more-the-better) approaches to form and functionally grounded type-thinking, yet it clearly takes side in the debate between empirical and theoretical type-construction as essential object-specific properties in the sense of Boissinot (1) cannot be deduced in a purely data-driven fashion. Boissinot’s proposal to re-think archaeological types from the perspective of different species of archaeological objects and their abstract material specificities is thought-provoking and we cannot stop wondering what fruits such interrogations would bear in relation to other kinds of objects such as lithics, metal artefacts, glass, and so forth. In addition, such meta-groupings are inherently problematic themselves, and they thus re-introduce old challenges as to how to separate the relevant super-wholes, technological genesis being an often-invoked candidate discriminator. The latter may suggest that we cannot but ultimately circle back on the human context of archaeological objects, even if we, for both theoretical and epistemological reasons, wish to embark on strictly object-oriented archaeologies in order to emancipate ourselves from the ‘contamination’ of language and in-built assumptions.

Bibliography 1. Boissinot, P. (2024). What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery, Zenodo, 7429330, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10718433 2. Fletcher, S.C., Palacios, P., Ruetsche, L., Shech, E. (2019). Infinite idealizations in science: an introduction. Synthese 196, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02069-6 3. Potochnik, A. (2017). Idealization and the aims of science (University of Chicago Press). https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226507194.001.0001 4. J. Winkelmann, J. (2023). On Idealizations and Models in Science Education. Sci & Educ 32, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00291-2 5. Potochnik, A. (2020). Idealization and Many Aims. Philosophy of Science 87, 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1086/710622 6. Pepper S. C. (1972). World hypotheses: a study in evidence, 7. print (University of California Press). 7. Sigaut, F. (1991). “Un couteau ne sert pas à couper, mais en coupant. Structure, fonctionnement et fonction dans l’analyse des objets” in 25 Ans d’études Technologiques En Préhistoire. Bilan et Perspectives (Association pour la promotion et la diffusion des connaissances archéologiques), pp. 21–34. 8. Shepard, A. O. (1956). Ceramics for the Archeologist (Carnegie Institution of Washington n° 609). 9. Birkhoff G. D. (1933). Aesthetic Measure (Harvard University Press). 10. Olsen, B. (2010). In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects (AltaMira Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/ept014 11. Olsen, B., Shanks, M., Webmoor, T., Witmore, C. (2012). Archaeology: the discipline of things (University of California Press). https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520954007 12. Boissinot, P. (2011). “Comment sommes-nous déficients ?” in L’archéologie Comme Discipline ? (Le Seuil), pp. 265–308. | What is a form? On the classification of archaeological pottery. | Philippe Boissinot | <p>The main question we want to ask here concerns the application of philosophical considerations on identity about artifacts of a particular kind (pottery). The purpose is the recognition of types and their classification, which are two of the ma... |  | Ceramics, Theoretical archaeology | Shumon Tobias Hussain | 2022-12-13 15:04:45 | View | |

10 Jan 2024

Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3DFlorian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269A valuable contribution to automated analysis of palaeolithic artefactsRecommended by Sebastian Hageneuer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lutz Schubert and 1 anonymous reviewer

In this paper (Linsel/Bullenkamp/Mara 2024), the authors propose an automatic system for scar-ridge-pattern detection on palaeolithic artefacts based on Morse Theory. Scare-Ridge pattern recognition is a process that is usually done manually while creating a drawing of the object itself. Automatic systems to detect scars or ridges exist, but only a small amount of them is utilizing 3D data. In addition to the scar-ridges detection, the authors also experiment in automatically detecting the operational sequence, the temporal relation between scars and ridges. As a result, they can export a traditional drawing as well as graph models displaying the relationships between the scars and ridges. After an introduction to the project and the practice of documenting palaeolithic artefacts, the authors explain their procedure in automatising the analysis of scars and ridges as well as their temporal relation to each other on these artefacts. To illustrate the process, an open dataset of lithic artefacts from the Grotta di Fumane, Italy, was used and 62 artefacts selected. To establish a Ground Truth, the artefacts were first annotated manually. The authors then continue to explain in detail each step of the automated process that follows and the results obtained. In the second part of the paper, the results are presented. First the results of the segmentation process shows that the average percentage of correctly labelled vertices is over 91%, which is a remarkable result. The graph modelling however shows some more difficulties, which the authors are aware of. To enhance the process, the authors rightfully aim to include datasets of experimental archaeology in the future. They also aim to develop a way of detecting the operational sequence automatically and precisely. This paper has great potential as it showcases exactly what Digital and Computational Archaeology is about: The development of new digital methods to enhance the analysis of archaeological data. While this procedure is still in development, the authors were able to present a valuable contribution to the automatization of analytical archaeology. By creating a step towards the machine-readability of this data, they also open up the way to further steps in machine learning within Archaeology. BibliographyLinsel, F., Bullenkamp, J. P., and Mara, H. (2024). Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D, Zenodo, 8296269, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8296269 | Linking Scars: Topology-based Scar Detection and Graph Modeling of Paleolithic Artifacts in 3D | Florian Linsel, Jan Philipp Bullenkamp & Hubert Mara | <p>Motivated by the concept of combining the archaeological practice of creating lithic artifact drawings with the potential of 3D mesh data, our goal in this project is not only to analyze the shape at the artifact level, but also to enable a mor... | Computational archaeology, Europe, Lithic technology, Upper Palaeolithic | Sebastian Hageneuer | 2023-09-01 23:03:59 | View | ||

01 Dec 2022

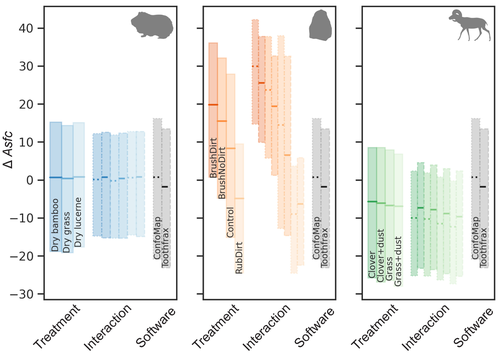

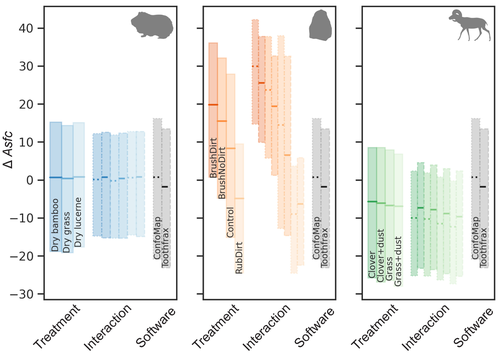

Surface texture analysis in Toothfrax and MountainsMap® SSFA module: Different software packages, different results?Ivan CALANDRA, Konstantin BOB, Gildas MERCERON, François BLATEYRON, Andreas HILDEBRANDT, Ellen SCHULZ-KORNAS, Antoine SOURON, Daniela E. WINKLER https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4671438An important comparison of software for Scale Sensitive Fractal Analysis : are ancient and new results compatible?Recommended by Alain Queffelec and Florent Rivals and Florent Rivals based on reviews by Antony Borel and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Antony Borel and 2 anonymous reviewers

The community of archaeologists, bioanthropologist and paleontologists relying on tools use-wear and dental microwear has grown in the recent years, mainly driven by the spread of confocal microscopes in the laboratories. If the diversity of microscopes is quite high, the main software used for 3D surface texture data analysis are mostly different versions of the same Mountains Map core. In addition to this software, since the beginning of 3D surface texture analysis in dental microwear, surface sensitive fractal analysis (SSFA) initially developed for industrial research (Brown & Savary, 1991) have been performed in our disciplines with the Sfrax/Toothfrax software for two decades (Ungar et al., 2003). This software being discontinued, these calculations have been integrated to the new versions of Mountains Map, with multi-core computing, full integration in the software and an update of the calculation itself. New research based on these standard parameters of surface texture analysis will be, from now on, mainly calculated with this new add-on of Mountains Map, and will be directly compared with the important literature based on the previous software. The question addressed by Calandra et al. (2022), gathering several prominent researchers in this domain including the Mountains Map developer F. Blateyron, is key for the future research: can we directly compare SSFA results from both software? Thanks to a Bayesian approach to this question, and comparing results calculated with both software on three different datasets (two on dental microwear, one on lithic raw materials), the authors show that the two software gives statistically different results for all surface texture parameters tested in the paper. Nevertheless, applying the new calculation to the datasets, they also show that the results published in original studies with these datasets would have been similar. Authors also claim that in the future, researchers will need to re-calculate the fractal parameters of previously published 3D surfaces and cannot simply integrate ancient and new data together. We also want to emphasize the openness of the work published here. All datasets have been published online and will be probably very useful for future methodological works. Authors also published their code for statistical comparison of datasets, and proposed a fully reproducible article that allowed the reviewers to check the content of the paper, which can also make this article of high interest for student training. This article is therefore a very important methodological work for the community, as noted by all three reviewers. It will certainly support the current transition between the two software packages and it is necessary that all surface texture specialists take these results and the recommendation of authors into account: calculate again data from ancient measurements, and share the 3D surface measurements on open access repositories to secure their access in the future. References Brown CA, and Savary G (1991) Describing ground surface texture using contact profilometry and fractal analysis. Wear, 141, 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(91)90269-Z Calandra I, Bob K, Merceron G, Blateyron F, Hildebrandt A, Schulz-Kornas E, Souron A, and Winkler DE (2022) Surface texture analysis in Toothfrax and MountainsMap® SSFA module: Different software packages, different results? Zenodo, 7219877, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7219877 Ungar PS, Brown CA, Bergstrom TS, and Walker A (2003) Quantification of dental microwear by tandem scanning confocal microscopy and scale-sensitive fractal analyses. Scanning: The Journal of Scanning Microscopies, 25, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/sca.4950250405 | Surface texture analysis in Toothfrax and MountainsMap® SSFA module: Different software packages, different results? | Ivan CALANDRA, Konstantin BOB, Gildas MERCERON, François BLATEYRON, Andreas HILDEBRANDT, Ellen SCHULZ-KORNAS, Antoine SOURON, Daniela E. WINKLER | <p>The scale-sensitive fractal analysis (SSFA) of dental microwear textures is traditionally performed using the software Toothfrax. SSFA has been recently integrated to the software MountainsMap® as an optional module. Meanwhile, Toothfrax suppor... |  | Computational archaeology, Palaeontology, Traceology | Alain Queffelec | Anonymous, John Charles Willman, Antony Borel | 2022-07-07 09:58:50 | View |

02 Mar 2024

A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasetsNimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733A new approach to Predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer

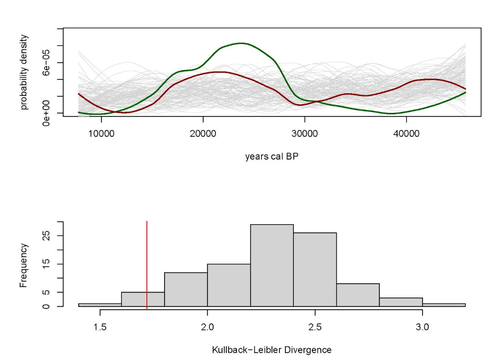

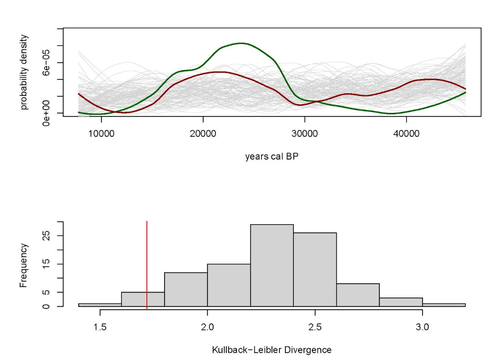

Various biological systems have been subjected to mathematical modelling to enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions among different species. Among these models, the predator-prey model holds a significant position. Its relevance stems not only from its application in biology, where it largely governs the coexistence of diverse species in open ecosystems, but also from its utility in other domains. Predator-prey dynamics have long been a focal point in population ecology, yet access to real-world data is confined to relatively brief periods, typically less than a century. Studying predator-prey dynamics over extended periods presents challenges due to the limited availability of population data spanning more than a century. The most extensive dataset is the hare-lynx records from the Hudson Bay Company, documenting a century of fur trade [1]. However, other records are considerably shorter, usually spanning decades [2,3]. This constraint hampers our capacity to investigate predator-prey interactions over centennial or millennial scales. Marom and Wolkowski [4] propose here that leveraging regional radiocarbon databases offers a solution to this challenge, enabling the reconstruction of predator-prey population dynamics over extensive timeframes. To substantiate this proposition, they draw upon examples from Pleistocene Beringia and the Holocene Judean Desert. This approach is highly relevant and might provide insight into ecological processes occurring at a time scale beyond the limits of current ecological datasets. The methodological approach employed in this article proposes that the summed probability distribution (SPD) of predator radiocarbon dates, which reflects changes in population size, will demonstrate either more or less variation than anticipated from random sampling in a homogeneous distribution spanning the same timeframe. A deviation from randomness would imply a covariation between predator and prey populations. This basic hypothesis makes no assumptions about the frequency, mechanism, or cause of predator-prey interactions, as it is assumed that such aspects cannot be adequately tested with the available data. If validated, this hypothesis would offer initial support for the idea that long-term regional radiocarbon data contain signals of predator-prey interactions. This approach could justify the construction of larger datasets to facilitate a more comprehensive exploration of these signal structures.

References [1] Elton, C. and Nicholson, M., 1942. The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada. J. Anim. Ecol. 11, 215–244. [2] Gilg, O., Sittler, B. and Hanski, I., 2009. Climate change and cyclic predator-prey population dynamics in the high Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01927.x [3] Vucetich, J.A., Hebblewhite, M., Smith, D.W. and Peterson, R.O., 2011. Predicting prey population dynamics from kill rate, predation rate and predator-prey ratios in three wolf-ungulate systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01855.x [4] Marom, N. and Wolkowski, U. (2024). A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets, BioRxiv, 566733, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733 | A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets | Nimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski | <p>Predator-prey interactions have been a central theme in population ecology for the past century, but real-world data sets only exist for recent, relatively short (<100 years) time spans. This limits our ability to study centennial/millennial... |  | Bioarchaeology, Environmental archaeology, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | 2023-12-12 14:37:22 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer