Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▼ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

24 Jun 2021

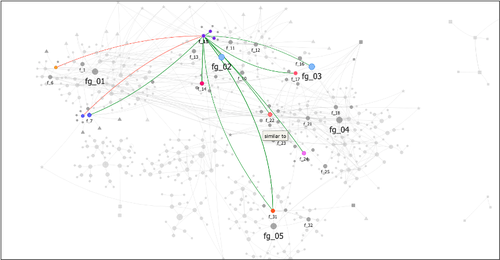

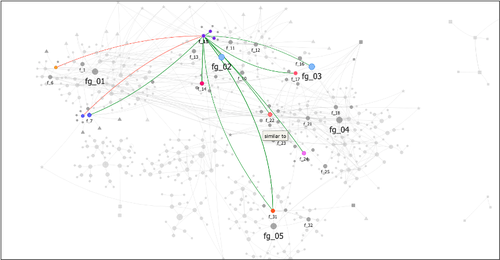

The strength of parthood ties. Modelling spatial units and fragmented objects with the TSAR method – Topological Study of Archaeological RefittingSébastien Plutniak https://osf.io/q2e69A practical computational approach to stratigraphic analysis using conjoinable material culture.Recommended by Hector A. Orengo based on reviews by Robert Bischoff, Matthew Peeples and 1 anonymous reviewerThe paper by Plutniak [1] presents a new method that uses refitting to help interpret stratigraphy using the topological distribution of conjoinable material culture. This new method opens up new avenues to the archaeological use of network analysis but also to assess the integrity of interpreted excavation layers. Beyond its evident applicability to standard excavation practice, the paper presents a series of characteristics that exemplify archaeological publication best practices and, as someone more versed in computational than in refitting studies I would like to comment upon. It was no easy task to find adequate reviewers for this paper as it combines techniques and expertise that are not commonly found together in individual researchers. However, Plutniak, with help from three reviewers, particularly M. Peeples, a leading figure in archaeological applications of network science, makes a considerable effort to be accessible to non-specialist archaeologists. The core Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting (TSAR) method is freely accessible as the R package archeofrag, which is available at the Comprehensive R Archive Network (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=archeofrag) that can be applied without the need to understand all its mathematical, graph theory and coding aspects. Beside these, an online interface including test data has been provided (https://analytics.huma-num.fr/Sebastien.Plutniak/archeofrag/), which aims to ease access to the method to those archaeologists inexperienced with R. Finally, supplementary material showing how to use the package and evaluating its potential through excellent examples is provided as both pdf and Rmw (Sweave) files. This is an important companion for the paper as it allows a better understanding of the methods presented in the paper and its practical application. The author shows particular care in testing the potential and capabilities of the method. For example, a function is provided “frag.observer.failure” to test the robustness of the edge count method against the TSAR method, which is able to prove that TSAR can deal well with incomplete information. As a further step in this direction both simulated and real field-acquired data are used to test the method which further proves that archeofrag is not only able to quantitatively assess the mixture of excavated layers but to propose meaningful alternatives, which no doubt will add an increased methodological consistency and thoroughness to previous quantitative approaches to material refitting work, even when dealing with very complex stratigraphies. All in all, this paper makes an important contribution to core archaeological practice through the use of innovative, reproducible and accessible computational methods. I fully endorse it for the conscious and solid methods it presents but also for its adherence to open publication practices. I hope that it can become of standard use in the reconstruction of excavated stratigraphical layers through conjoinable material culture.

[1] Plutniak, S. 2021. The Strength of Parthood Ties. Modelling Spatial Units and Fragmented Objects with the TSAR Method – Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting. OSF Preprints, q2e69, ver. 3 Peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/q2e69. | The strength of parthood ties. Modelling spatial units and fragmented objects with the TSAR method – Topological Study of Archaeological Refitting | Sébastien Plutniak | <p>Refitting and conjoinable pieces have long been used in archaeology to assess the consistency of discrete spatial units, such as layers, and to evaluate disturbance and post-depositional processes. The majority of current methods, despite their... | Computational archaeology, Taphonomy | Hector A. Orengo | 2021-01-14 18:31:01 | View | ||

19 Jun 2020

Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilitiesCédric Gaucherel and Camille Noûs https://doi.org/10.31233/osf.io/wn5zaThe means of complexity in a lithic reduction sequenceRecommended by Marta Arzarello based on reviews by Antony Borel and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Antony Borel and 1 anonymous reviewer

The paper entitled “Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities” [1] submitted by C. Gaucherel and C. Noûs represents an interesting reflection about the possibilities to detect the human cognitive abilities in relation to the lithic production. The definition and the study of human cognitive abilities during the Lower Palaeolithic it has always been a complex field of investigation. The relation between the technical skills (lithic production) and the emergence of the linguistic abilities is not easy to investigate due to the difficulty of finding objective data to refer to. The proposition, made by C. Gaucherel and C. Noûs, of a formal grammar of knapping as a method to study the syntactical organisation of the reduction sequences, constitute a new and theoretical useful approach. In order to effectively and precisely define the gestures linked to a specific reduction sequence, for example that of the handaxes shaping, a very large number of variables should be taken into consideration (morphology and quality of the raw material, experience of the knapper, context, percussion technique, forecast of use of the handaxe, etc.). But since a simplification, that brings more elements than the classic one [2,3] is needed, the “action grammar approach” can be a good instrument to detect the common element in a shaping reduction sequence. Furthermore, one of the advantages of the proposed methodology lies in the fact that the definition of the different STs (Stone Technology) can be done according to the technological specific characteristics to be studied and to the type of instrument produced. The deconstruction of knapping sequences could help to detect the degree of complexity of the different steps of the reduction sequences also thanks to the identification of the sub-actions types. The increasing/decreasing of complexity is a very complicate concept in lithic technology. Since at the base of the lithic production there are two basic concepts (angle between the striking platform and the debitage surface - convexity of the debitage/façonnage surface) which are simply declined in an increasingly complex way, it is not easy to define uniquely in what exactly consists the increase in complexity. The approach proposed in the paper “Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities” can help to have new evidences, according to the identification of the required cognitive abilities. The proposed example of formal grammar still needs to be confirmed on archaeological collections, but it is probable that a practical application will allow to further develop the methodology and possibly to highlight additional possibilities of the approach. Bibliography [1] Gaucherel, C. and Noûs C. (2020). Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities. Paleorxiv, wn5za, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Archaeology. doi: 10.31233/osf.io/wn5za | Platforms of Palaeolithic knappers reveal complex linguistic abilities | Cédric Gaucherel and Camille Noûs | <p>Recent studies in cognitive neurosciences have postulated a possible link between manual praxis such as tool-making and human languages. If confirmed, such a link opens significant avenues towards the study of the evolution of natural languages... |  | Africa, Ancient Palaeolithic, Lithic technology, Theoretical archaeology | Marta Arzarello | 2020-04-30 14:18:26 | View | |

02 Mar 2024

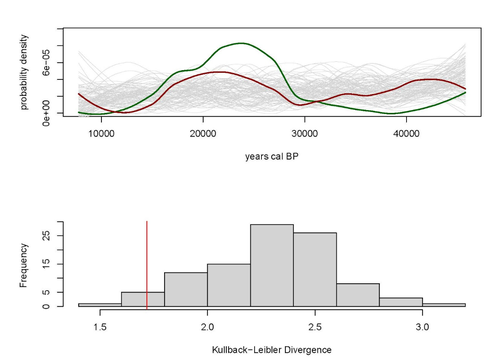

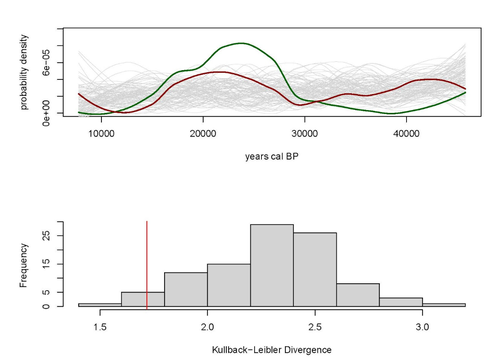

A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasetsNimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733A new approach to Predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Ruth Blasco based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jesús Rodríguez, Miriam Belmaker and 1 anonymous reviewer

Various biological systems have been subjected to mathematical modelling to enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions among different species. Among these models, the predator-prey model holds a significant position. Its relevance stems not only from its application in biology, where it largely governs the coexistence of diverse species in open ecosystems, but also from its utility in other domains. Predator-prey dynamics have long been a focal point in population ecology, yet access to real-world data is confined to relatively brief periods, typically less than a century. Studying predator-prey dynamics over extended periods presents challenges due to the limited availability of population data spanning more than a century. The most extensive dataset is the hare-lynx records from the Hudson Bay Company, documenting a century of fur trade [1]. However, other records are considerably shorter, usually spanning decades [2,3]. This constraint hampers our capacity to investigate predator-prey interactions over centennial or millennial scales. Marom and Wolkowski [4] propose here that leveraging regional radiocarbon databases offers a solution to this challenge, enabling the reconstruction of predator-prey population dynamics over extensive timeframes. To substantiate this proposition, they draw upon examples from Pleistocene Beringia and the Holocene Judean Desert. This approach is highly relevant and might provide insight into ecological processes occurring at a time scale beyond the limits of current ecological datasets. The methodological approach employed in this article proposes that the summed probability distribution (SPD) of predator radiocarbon dates, which reflects changes in population size, will demonstrate either more or less variation than anticipated from random sampling in a homogeneous distribution spanning the same timeframe. A deviation from randomness would imply a covariation between predator and prey populations. This basic hypothesis makes no assumptions about the frequency, mechanism, or cause of predator-prey interactions, as it is assumed that such aspects cannot be adequately tested with the available data. If validated, this hypothesis would offer initial support for the idea that long-term regional radiocarbon data contain signals of predator-prey interactions. This approach could justify the construction of larger datasets to facilitate a more comprehensive exploration of these signal structures.

References [1] Elton, C. and Nicholson, M., 1942. The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada. J. Anim. Ecol. 11, 215–244. [2] Gilg, O., Sittler, B. and Hanski, I., 2009. Climate change and cyclic predator-prey population dynamics in the high Arctic. Glob. Chang. Biol. 15, 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01927.x [3] Vucetich, J.A., Hebblewhite, M., Smith, D.W. and Peterson, R.O., 2011. Predicting prey population dynamics from kill rate, predation rate and predator-prey ratios in three wolf-ungulate systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1236–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01855.x [4] Marom, N. and Wolkowski, U. (2024). A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets, BioRxiv, 566733, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566733 | A note on predator-prey dynamics in radiocarbon datasets | Nimrod Marom, Uri Wolkowski | <p>Predator-prey interactions have been a central theme in population ecology for the past century, but real-world data sets only exist for recent, relatively short (<100 years) time spans. This limits our ability to study centennial/millennial... |  | Bioarchaeology, Environmental archaeology, Palaeontology, Paleoenvironment, Zooarchaeology | Ruth Blasco | 2023-12-12 14:37:22 | View | |

26 Sep 2022

The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspectiveSolange Rigaud, John O’Hara, Laurent Charles, Elena Man-Estier, Patrick Paillet https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/z7pqgCaching up with the study of the procurement of symbolic raw materials in the Upper PalaeolithicRecommended by Beatrice Demarchi based on reviews by Begoña Soler Mayor , Catherine Dupont and Lawrence StrausThe manuscript "The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective" by Solange Rigaud and colleagues (Rigaud et al. 2022) is a perfect demonstration that appropriate scientific methodologies can be used effectively in order to enhance the historical value of findings from “old” collections, despite the lack of secure stratigraphic and contextual data. The shell assemblage (n = 377) investigated here (from Rochereil, Dordogne) had been excavated during the first half of the 20th century (Jude 1960) and reported in 1993 (Taborin 1993), but only this recent analysis revealed that it was composed of largely unmodified mollusc shells, most of allochthonous origin. Rigaud et al. interpret this finding as the raw materials used to produce personal ornaments. This is especially significant, because the focus of research has been on the manufacture, use and exchange of personal ornaments in prehistory, much less so on the procurement of the raw materials. As such, the manuscript adds substantially to the growing literature on Magdalenian social networks. The authors carried out detailed taxonomic analysis based on morphological and morphometric characteristics and identified at least nine different species, including Dentalium sp., Ocenebra erinaceus, Tritia reticulata and T. gibbosula, as well as some bivalve specimens (Mytilus, Glycymeris, Spondylus, Pecten). Most of the species are commonly found in personal ornament assemblages from the Magdalenian, reflecting intentional selection (also shown by the size sorting of some of the taxa), and cultural continuity. However, microscopic examinations revealed securely-identified anthropogenic modifications on a very limited number of specimens: one Glycymeris valve (used as an ochre container), one Cardiidae valve (presence of a groove), one perforated Tritia gibbosula and two perforated Tritia reticulata bearing striations. The authors interpret this combination of anthropogenic vs natural “signals” as signifying that the assemblage represents raw material selected and stored for further processing. Assessing the provenance and age of the shells is therefore paramount: the shells found at Rochereil belong to species that can be found on both the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. Assuming that molluscan taxa distribution in the past is comparable to that for the present day, this implies the exploitation of two catchment areas and long-distance transportation to the site: taking sea-level changes into account, during the Magdalenian the Mediterranean used to lie at a distance of 350 km from Rochereil, and the Atlantic was not significantly closer (~200 km). Importantly, exploitation of fossil shells cannot be discounted on the basis of the data presented here; direct dating of some of the specimens (e.g. by radiocarbon, or amino acid racemisation geochronology) would be beneficial to clarify this issue and in general to improve chronological control on the accumulation of shells. Nonetheless, the authors argue that the closest fossil deposits also lie more than 200 km away from the site, thus the material is allochthonous in origin. In synthesis, the Rochereil assemblage represents an important step towards a better understanding of the procurement chain and of the production of ornaments during the European Upper Palaeolithic. References Jude, P. E. (1960). La grotte de Rocherreil: station magdalénienne et azilienne, Masson. Rigaud, S., O'Hara, J., Charles, L., Man-Estier, E. and Paillet, P. (2022) The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective. SocArXiv, z7pqg, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/z7pqg Taborin, Y. (1993). La parure en coquillage au Paléolithique, CNRS éditions. | The management of symbolic raw materials in the Late Upper Paleolithic of South-Western France: a shell ornaments perspective | Solange Rigaud, John O’Hara, Laurent Charles, Elena Man-Estier, Patrick Paillet | <p>Personal ornaments manufactured on marine and fossil shell are a significant element of Upper Palaeolithic symbolic material culture, and are often found at considerable distances from Pleistocene coastlines or relevant fossil deposits. Here, w... |  | Europe, Symbolic behaviours, Upper Palaeolithic | Beatrice Demarchi | 2022-04-23 19:20:02 | View | |

02 Feb 2024

Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley CollectionRaykovska Miglena, Jones Kristen, Klecherova Hristina, Alexandrov Stefan, Petkov Nikolay, Hristova Tanya, Ivanov Georgi https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8027548Out of the storeroom and into the virtualRecommended by Jitte Waagen based on reviews by Alicia Walsh and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Alicia Walsh and 1 anonymous reviewer

This paper (Raykovska et al. 2023) discusses the digital documentation techniques and development of a virtual exhibition for artefacts retrieved from the necropolis of Baley, Bulgaria. The principal aim of this particular project is a solid one, trying to provide a solution to display artefacts that would otherwise remain hidden in museum storerooms. The paper describes how through a combination of 3D scanning and photogrammetry high quality 3D models have been produced, and provide content for an online virtual exhibition for the scientific community but also the larger public. It is a well-written and concise paper, in which the information on developed methods and techniques are transparently described, and various important aspects of digitization workflows, such as the importance of storing raw data, are addressed. The paper is a timely discussion on this subject, as strategies to develop digital artefact collections and what to do with those are increasingly being researched. Specifically, it discusses a workflow and its results, both in great detail. Although critical reflection on the process, goals and results from various perspectives would have been a valuable addition to the paper (cf., Jeffra 2020, Paardekoper 2019), it nonetheless provides a good practice example of how to approach the creation of a virtual museum. Those who consider projects concerning digital documentation of archaeological artefacts as well as the creation of virtual spaces to use those in for research, education or valorisation purposes would do well to read this paper carefully. References Jeffra, C., Hilditch, J., Waagen, J., Lanjouw, T., Stoffer, M., de Gelder, L., and Kim, M. J. (2020). Blending the Material and the Digital: A Project at the Intersection of Museum Interpretation, Academic Research, and Experimental Archaeology. The EXARC Journal, 2020(4). https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10541 Paardekooper, R.P. (2019). Everybody else is doing it, so why can’t we? Low-tech and High-tech approaches in archaeological Open-Air Museums. The EXARC Journal, 2019(4). https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10457/ Raykovska, M., Jones, K., Klecherova, H., Alexandrov, S., Petkov, N., Hristova, T., and Ivanov, G. (2023). Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley Collection. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10091870 | Implementing Digital Documentation Techniques for Archaeological Artifacts to Develop a Virtual Exhibition: the Necropolis of Baley Collection | Raykovska Miglena, Jones Kristen, Klecherova Hristina, Alexandrov Stefan, Petkov Nikolay, Hristova Tanya, Ivanov Georgi | <p>Over the past decade, virtual reality has been quickly growing in popularity across disciplines including the field of archaeology and cultural heritage. Despite numerous artifacts being uncovered each year by archaeological excavations around ... |  | Ceramics, Computational archaeology, Conservation/Museum studies | Jitte Waagen | 2023-06-12 14:02:44 | View | |

Yesterday

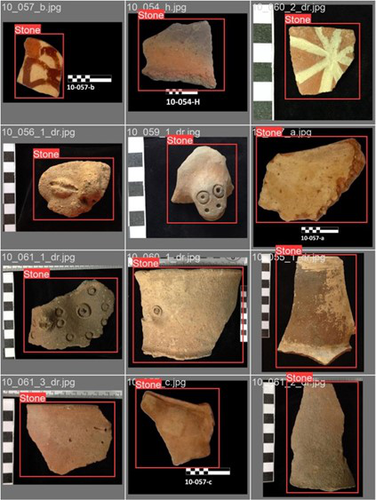

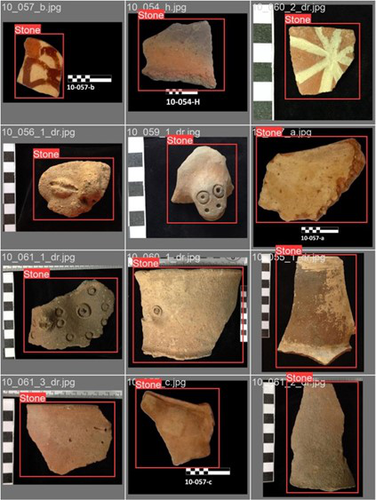

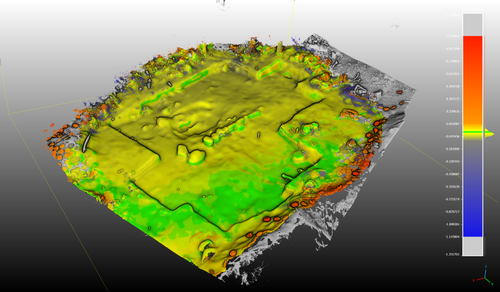

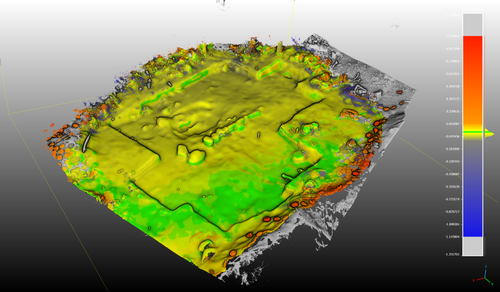

Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard PracticesSharp Kayeleigh, Christofis Brooklyn, Eslamiat Hossein, Nepal Upesh, Osores Mendives Carlos https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307612A step forward in detecting small objects in UAV data for archaeological surveyingRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In this paper [1], the authors describe how they apply machine learning with YOLOv5 to classify visual data, aiming to enhance understanding of archaeological phenomena before conducting destructive fieldwork. Despite challenges, the integration of machine learning with remote sensing technology was seen as transformative, enabling precise recording of areas of interest and assessment of environmental risk factors. The paper discusses successes, failures, and future directions in machine learning research, emphasising the need for standardisation and integration of streamlined methods. The application of machine learning techniques facilitates non-destructive analysis of material culture records, improving conservation efforts and offering insights into both past and contemporary phenomena. While the initial use of YOLOv5 showed potential for consistent detection of archaeological features, further refinement and dataset enlargement are deemed necessary for broader application in non-destructive archaeological surveying. The authors advocate for the integration of machine learning tools in archaeological research to save time, resources, and promote ethical digital recording practices. They highlight the importance of standardised methodologies to enhance credibility and reproducibility, aiming to contribute to the ongoing dialogue in computational archaeology. Overall, I think this paper is a good step forward in detecting small objects in UAV data, and contains useful information for similar studies. The aim towards greater reproducibility and standardisation is of course shared more widely in the machine learning community, and this study is a good example of how to approach this. References [1] Sharp, K., Christofis, B., Eslamiat, H., Nepal, U. and Osores Mendives, C. (2024). Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard Practices. Zenodo, 8307612, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307612 | Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard Practices | Sharp Kayeleigh, Christofis Brooklyn, Eslamiat Hossein, Nepal Upesh, Osores Mendives Carlos | <p>Our collaborative work began in 2019 with the intent to overcome obstacles that had arisen from the inability to access curated artifact collections from remote locations. It was our specific aim to not only create digital twins of excavated ob... |  | Ceramics, Computational archaeology, Remote sensing, South America | Alex Brandsen | 2023-09-01 09:56:18 | View | |

06 Oct 2023

From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editionsAuth. Frederic; Rösler, Katja; Domscheit, Wenke; Hofmann, Kerstin P. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7304578Revitalising archaeological corpus publications through digitisation – the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae as exemplary casesRecommended by Felix Riede, Sébastien Plutniak and Shumon Tobias Hussain and Shumon Tobias Hussain based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer and Adéla Sobotkova

The paper entitled “From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions” submitted by Frederic Auth and colleagues discusses how those rich and often meticulously illustrated catalogues of particular find classes that exist in many corners of archaeology can be brought to the cutting edge of contemporary research through digitisation. This paper was first developed for a special conference session convened at the EAA annual meeting in 2021 and is intended for an edited volume on the topic of typology, taxonomy, classification theory, and computational approaches in archaeology. Auth et al. (2023) begin with outlining the useful notion of the ‘thing-edition’ originally coined by Kerstin Hofmann in the context of her work with the many massive corpora of finds that have characterised, in particular, earlier archaeological knowledge production in Germany (Hofmann et al. 2019; Hofmann 2018). This work critically examines changing trends in the typological characterisation and recording of various find categories, their theoretical foundations or lack thereof and their legacy on contemporary practice. The present contribution focuses on what happens with such corpora when they are integrated into digitisation projects, specifically the efforts by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), the so-called iDAI.world and in regard to two Roman-era material culture groups, the Corpus der römischen Funde im europäischen Barbaricum (Roman finds from beyond the empire’s borders in eight printed volumes covering thousands of finds of various categories), and the Conspectus Formarum Terrae Sigillatae Modo Confectae (Roman plain ware). Drawing on Bruno Latour’s (2005) actor-network theory (ANT), Auth et al. discuss and reflect on the challenges met and choices to be made when thing-editions are to be transformed into readily accessible data, that is as linked to open, usable data. The intellectual and infrastructural workload involved in such digitisation projects is not to be underestimated. Here, the contribution by Auth et al. excels in the manner that it does not present the finished product – the fully digitised corpora – but instead offers a glimpse ‘under the hood’ of the digitisation process as an interaction between analogue corpus, research team, and the technologies at hand. These aspects were rarely addressed in the literature, rooted in the 1970s early work (Borillo and Gardin 1974; Gaines 1981), on archaeological computerised databases, focused on technical dimensions (see Rösler 2016 for an exception). Their paper can so also be read in the broader context of heterogeneous computer-assisted knowledge ecologies and ‘mangles of practice’ (see Pickering and Guzik 2009) in which practitioners and technological structures respond to each other’s needs and attempt to cooperate in creative ways. As such, Auth et al.’s considerations not least offer valuable resources for Science and Technology Studies-inspired discussions on the cross-fertilization of archaeological theory, practice and currently emerging material and virtual research infrastructures and can be read in conjunction to Gavin Lucas’ (2022) paper on ‘machine epistemology’ due to appear in the same volume. Perhaps more importantly, however, the work by Auth and colleagues (2023) exemplifies the due diligence required in not merely turning a catalogue from paper to digital document but in transforming such catalogues into long-lasting and patently usable repositories of generations of scholars to come. Deploying the Latourian notions of trade-off and recursive reference, Auth et al. first examine the structure, strengths, and weakness of the two corpora before moving on to showing how the freshly digitised versions offer new and alternative ways of analysing the archaeological material at hand, notably through immediate visualisation opportunities, through ceramic form combinations, and relational network diagrams based on the data inherent in the respective thing-editions. Catalogues including basic descriptions and artefact illustrations exist for most if not all archaeological periods. They constitute an essential backbone of archaeological work as repeated access to primary material is impractical if not impossible. The catalogues addressed by Auth et al. themselves reflect major efforts on behalf of archaeological experts to arrive at clear and operational classifications in a pre-computerised era. The continued and expanded efforts by Auth and colleagues build on these works and clearly demonstrate the enormous analytical potential to make such data not merely more accessible but also more flexibly interoperable. Their paper will therefore be an important reference for future work with similar ambitions facing similar challenges. References Auth, Frederic, Katja Rösler, Wenke Domscheit, and Kerstin P. Hofmann. 2023. “From Paper to Byte: A Workshop Report on the Digital Transformation of Two Thing Editions.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8214563 Borillo, Mario, and Jean-Claude Gardin. 1974. Les Banques de Données Archéologiques. Marseille: Éditions du CNRS. Gaines, Sylvia W., ed. 1981. Data Bank Applications in Archaeology. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. Hofmann, Kerstin P. 2018. “Dingidentitäten Und Objekttransformationen. Einige Überlegungen Zur Edition von Archäologischen Funden.” In Objektepistemologien. Zum Verhältnis von Dingen Und Wissen, edited by Markus Hilgert, Kerstin P. Hofmann, and Henrike Simon, 179–215. Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 59. Berlin: Edition Topoi. https://dx.doi.org/10.17171/3-59 Hofmann, Kerstin P., Susanne Grunwald, Franziska Lang, Ulrike Peter, Katja Rösler, Louise Rokohl, Stefan Schreiber, Karsten Tolle, and David Wigg-Wolf. 2019. “Ding-Editionen. Vom Archäologischen (Be-)Fund Übers Corpus Ins Netz.” E-Forschungsberichte des DAI 2019/2. E-Forschungsberichte Des DAI. Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2236/6674 Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lucas, Gavin. 2022. “Archaeology, Typology and Machine Epistemology.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7622162 Pickering, Andrew, and Keith Guzik, eds. 2009. The Mangle in Practice: Science, Society, and Becoming. The Mangle in Practice. Science and Cultural Theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Rösler, Katja. 2016. “Mit Den Dingen Rechnen: ‚Kulturen‘-Forschung Und Ihr Geselle Computer.” In Massendinghaltung in Der Archäologie. Der Material Turn Und Die Ur- Und Frühgeschichte, edited by Kerstin P. Hofmann, Thomas Meier, Doreen Mölders, and Stefan Schreiber, 93–110. Leiden: Sidestone Press. | From paper to byte: An interim report on the digital transformation of two thing editions | Auth. Frederic; Rösler, Katja; Domscheit, Wenke; Hofmann, Kerstin P. | <p>One specific form of publication for archaeological objects are catalogues, atlases and corpora. Kerstin Hofmann has introduced the term ‘Ding-Editionen’ (thing editions) for this category of publications that present their data in lists, short... |  | Antiquity, Computational archaeology, Dating, Theoretical archaeology | Felix Riede | 2022-11-08 16:00:49 | View | |

31 Jan 2024

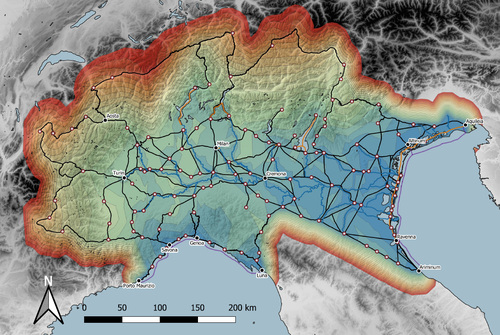

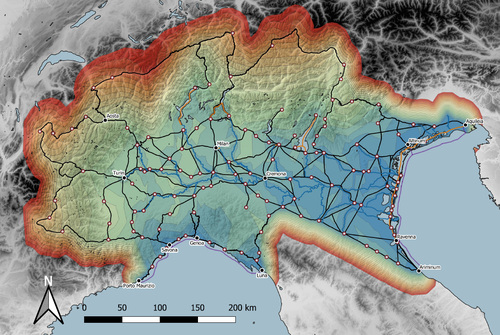

Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman periodJames Page https://zenodo.org/records/7971399Modelling Roman Transport Infrastructure in Northern ItalyRecommended by Andrew McLean based on reviews by Pau de Soto and Adam PažoutStudies of the economy of the Roman Empire have become increasingly interdisciplinary and nuanced in recent years, allowing the discipline to make great strides in data collection and importantly in the methods through which this increasing volume of data can be effectively and meaningfully analysed [see for example 1 and 2]. One of the key aspects of modelling the ancient economy is understanding movement and transport costs, and how these facilitated trade, communication and economic development. With archaeologists adopting more computational techniques and utilising GIS analysis beyond simply creating maps for simple visualisation, understanding and modelling the costs of traversing archaeological landscapes has become a much more fruitful avenue of research. Classical archaeologists are often slower to adopt these new computational techniques than others in the discipline. This is despite (or perhaps due to) the huge wealth of data available and the long period of time over which the Roman economy developed, thrived and evolved. This all means that the Roman Empire is a particularly useful proving ground for testing and perfecting new methodological developments, as well as being a particularly informative period of study for understanding ancient human behaviour more broadly. This paper by Page [3] then, is well placed and part of a much needed and growing trend of Roman archaeologists adopting these computational approaches in their research. Page’s methodology builds upon De Soto’s earlier modelling of transport costs [4] and applies it in a new setting. This reflects an important practice which should be more widely adopted in archaeology. That of using existing, well documented methodologies in new contexts to offer wider comparisons. This allows existing methodologies to be perfected and tested more robustly without reinventing the wheel. Page does all this well, and not only builds upon De Soto’s work, but does so using a case study that is particularly interesting with convincing and significant results. As Page highlights, Northern Italy is often thought of as relatively isolated in terms of economic exchange and transport, largely due to the distance from the sea and the barriers posed by the Alps and Apennines. However, in analysing this region, and not taking such presumptions for granted, Page quite convincingly shows that the waterways of the region played an important role in bringing down the cost of transport and allowed the region to be far more interconnected with the wider Roman world than previous studies have assumed. This article is clearly a valuable and important contribution to our understanding of computational methods in archaeology as well as the economy and transport network of the Roman Empire. The article utilises innovative techniques to model transport in an area of the Roman Empire that is often overlooked, with the economic isolation of the area taken for granted. Having high quality research such as this specifically analysing the region using the most current methodologies is of great importance. Furthermore, developing and improving methodologies like this allow for different regions and case studies to be analysed and directly compared, in a way that more traditional analyses simply cannot do. As such, Page has demonstrated the importance of reanalysing traditional assumptions using the new data and analyses now available to archaeologists. References [1] Brughmans, T. and Wilson, A. (eds.) (2022). Simulating Roman Economies: Theories, Methods, and Computational Models. Oxford. [2] Dodd, E.K. and Van Limbergen, D. (eds.) (2024). Methods in Ancient Wine Archaeology: Scientific Approaches in Roman Contexts. London ; New York. [3] Page, J. (2024). Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman period, Zenodo, 7971399, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7971399 [4] De Soto P (2019). Network Analysis to Model and Analyse Roman Transport and Mobility. In: Finding the Limits of the Limes. Modelling Demography, Economy and Transport on the Edge of the Roman Empire. Ed. by Verhagen P, Joyce J, and Groenhuijzen M. Springer Open Access, pp. 271–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04576-0_13 | Rivers vs. Roads? A route network model of transport infrastructure in Northern Italy during the Roman period | James Page | <p>Northern Italy has often been characterised as an isolated and marginal area during the Roman period, a region constricted by mountain ranges and its distance from major shipping lanes. Historians have frequently cited these obstacles, alongsid... |  | Classic, Computational archaeology | Andrew McLean | 2023-05-28 15:11:31 | View | |

02 Sep 2023

Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation ToolsNikolai Paukkonen https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7954534The Potential of Mobile 3D Documentation using Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 ProRecommended by Ying Tung Fung based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and 1 anonymous reviewerI am pleased to recommend the paper titled "Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools" for consideration and publication as a preprint (Paukkonen, 2023). The paper addresses a timely and relevant topic within the field of archaeology and offers valuable insights into the evolving landscape of 3D documentation methods. The advances in technology over the past decade have brought about significant changes in archaeological documentation practices. This paper makes a valuable contribution by discussing the emergence of affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation. Given the constraints that many archaeologists face with limited resources and tight timeframes, the comparison between photogrammetry based on a video captured by a DJI Osmo Pocket gimbal camera and iPhone 12 Pro LiDAR scans is of great significance. The research presented in the paper showcases a practical application of these new technologies in the context of a Finnish Early Modern period archaeological project. By comparing the acquisition processes and evaluating the accuracy, precision, ease of use, and time constraints associated with each method, the authors provide a comprehensive assessment of their potential for archaeological fieldwork. This practical approach is a commendable aspect of the paper, as it not only explores the technical aspects but also considers the practical implications for archaeologists on the ground. Furthermore, the paper appropriately addresses the limitations of these technologies, specifically highlighting their potential inadequacy for projects requiring a higher level of precision, such as Neolithic period excavations. This nuanced perspective adds depth to the discussion and provides a realistic portrayal of the strengths and limitations of the new documentation methods. In conclusion, the paper offers valuable insights into the future of 3D field documentation for archaeologists. The authors' thorough evaluation and practical approach make this study a valuable resource for researchers, practitioners, and professionals in the field. I believe that this paper would be an excellent addition to PCIArchaeology and would contribute significantly to the ongoing dialogue within the archaeological community. References Paukkonen, N. (2023) Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools, Zenodo, 8281263, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8281263 | Towards a Mobile 3D Documentation Solution. Video Based Photogrammetry and iPhone 12 Pro as Fieldwork Documentation Tools | Nikolai Paukkonen | <p>New affordable equipment suitable for 3D fieldwork documentation has appeared during the last years. Both photogrammetry and laser scanning are becoming affordable for archaeologists, who often work with limited resources and tight time constra... |  | Europe, Post-medieval, Remote sensing | Ying Tung Fung | 2023-05-21 21:32:33 | View | |

29 Jan 2024

Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept researchJ.Y Blaise, I.Dudek, L.Bergerot, G.Simon https://zenodo.org/record/79831633D Models, Knowledge and Visualization: a prototype for 3D virtual models according to plausible criteriaRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Robert Bischoff and Louise TharandtThe construction of 3D realities is deeply embedded in archaeological practices. From sites to artifacts, archaeology has dedicated itself to creating digital copies for the most varied purposes. The paper “Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's 3 scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research” (Jean-Yves et al 2024) represents an advance, in the sense that it does not just deal with a three-dimensional theory for archaeological practice, but rather offers proposals regarding the epistemic component, how it is possible to represent knowledge through the workflow of 3D virtual reconstructions themselves. The authors aim to unite three main axes - knowledge modeling, visual encoding and 3D content reuse - (Jean-Yves et al 2024: 2), which, for all intents and purposes, form the basis of this article. With regard to the first aspect, this work questions how it is possible to transmit the knowledge we want to a 3D model and how we can optimize this epistemic component. A methodology based on plausibility criteria is offered, which, for the archaeological field, offers relevant space for reflection. Given our inability to fully understand the object or site that is the subject of the 3D representation, whether in space or time, building a method based on probabilistic categories is probably one of the most realistic approaches to the realities of the past. Thus, establishing a plausibility criterion allows the user to question the knowledge that is transmitted through the representation, and can corroborate or refute it in future situations. This is because the role of reusing these models is of great interest to the authors, a perfectly justifiable sentiment, as it encourages a critical view of scientific practices. Visual encoding is, in terms of its conjunction with knowledge practices, a key element. The notion of simplicity under Maeda's (2006) design principles not only represents a way of thinking that favors operability, but also a user-friendly design in the prototype that the authors have created. This is also visible when it comes to the reuse of parts of the models, in a chronological logic: adapting the models based on architectural elements that can be removed or molded is a testament to intelligent design, whereby instead of redoing models in their entirety, they are partially used for other purposes. All these factors come together in the final prototype, a web application that combines relational databases (RDBMS) with a data mapper (MassiveJS), using the PHP programming language. The example used is the Marmoutier Abbey hostelry, a centuries-old building which, according to the sources presented, has evolved architecturally over several centuries ((Jean-Yves et al 2024: 8). These states of the building are represented visually through architectural elements based on their existence, location, shape and size, always in terms of what is presented as being plausible. This allows not only the creation of a matrix in which various categories are related to various architectural elements, but also a visual aid, through a chromatic spectrum, of the plausibility that the authors are aiming for. In short, this is an article that seeks to rethink the degree of knowledge we can obtain through 3D visualizations and that does not take models as static, but rather realities that must be explored, recycled and reinterpreted in the light of different data, users and future research. For this reason, it is a work of great relevance to theoretical advances in 3D modeling adapted to archaeology.

References Blaise, J.-Y., Dudek, I., Bergerot, L. and Gaël, S. (2024). Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research, Zenodo, 7983163, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10496540 John Maeda. (2006). The Laws of Simplicity. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. | Visual encoding of a 3D virtual reconstruction's scientific justification: feedback from a proof-of-concept research | J.Y Blaise, I.Dudek, L.Bergerot, G.Simon | <p> 3D virtual reconstructions have become over the last decades a classical mean to communicate about analysts’ visions concerning past stages of development of an edifice or a site. However, they still today remain quite often a one-s... |  | Computational archaeology, Spatial analysis | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-05-30 00:43:03 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Alain Queffelec

Marta Arzarello

Ruth Blasco

Otis Crandell

Luc Doyon

Sian Halcrow

Emma Karoune

Aitor Ruiz-Redondo

Philip Van Peer