Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

14 May 2024

Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methodsChrisowalandis Deligio, Karsten Tolle, David Wigg-Wolf https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8301464A demonstration of the use and finetuning of existing machine learning tools for analysing large complexes of coinsRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

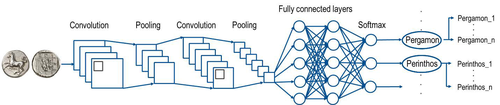

The paper outlines the ClaReNet project's exploration of computer-based methods for classifying Celtic coin series, specifically focusing on a hoard from Jersey [1]. They collaborated with Jersey Heritage and numismatists, utilising a large dataset of coin images. The process involves stages such as pre-sorting, size-based sorting, class/type identification, and die studies. They employed IT methods, including object detection and unsupervised learning, followed by supervised learning for data refinement. Collaboration with numismatic experts ensured data quality. The study highlighted challenges in classifying coins, suggesting techniques like image matching alongside convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The results demonstrate the efficacy of semi-automatic processes in coin classification, emphasising the importance of human-computer collaboration for successful outcomes. Overall, this is a good paper, showing how we as archaeologists and numismatics can use existing tools and finetune them for our purposes; without the need for huge domain specific datasets. This research and related papers show how we can more effectively deal with the increasingly bigger data we deal with, saving time on the monotonous and labour intensive tasks, leaving us more time to deal with the big picture. An important strength of the work is the provided public software repository and the dataset. The paper is well written, and a number of images illustrate the methodology as well as the objects used. Reference [1] Deligio, C., Tolle, K., and Wigg-Wolf, D. (2024). Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methods. Zenodo, 8301464, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8301464

| Supporting the analysis of a large coin hoard with AI-based methods | Chrisowalandis Deligio, Karsten Tolle, David Wigg-Wolf | <p>In the project "Classifications and Representations for Networks: From types and characteristics to linked open data for Celtic coinages" (ClaReNet) we had access to image data for one of the largest Celtic coin hoards ever found: Le Câtillon I... |  | Computational archaeology | Alex Brandsen | 2023-08-30 15:31:16 | View | |

07 May 2024

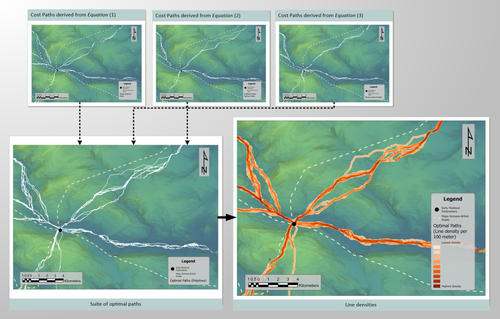

Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West EnglandWyatt Wilcox https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7999149Moving away from the ritual deposition: hoards from the Viking Age, Least Cost Paths and reused Roman RoadsRecommended by Ronald Visser based on reviews by Sam Leggett and Scott Madry based on reviews by Sam Leggett and Scott Madry

I had the pleasure of reading ‘Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England’ by Wyatt O. Wilcox (Wilcox 2024a). It is an honour to recommend this paper. The aim of this study is to research the relationship of 18 Viking Age hoards and their transport and depositional locations. This is studied in relation to the Roman road network and the landscape using least cost path analyses. Single finds from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (https://finds.org.uk/) are also incorporated in the study. The study deals with the distance of these Viking Age finds to these roads/least-cost-paths and the final interpretation moves away from ritual interpretation of these finds to a more mundane explanation. I feel that this could potentially open discussion also for hoards from other periods. While both reviewers (Sam Leggett and Scott Madry) presented various suggestions to improve the first submitted version of the paper, the author has done a tremendous job to improve the paper based on the comments and even beyond these comments. The author has also deposited the Jypiter-notebook online (Wilcox 2024b), showing that he is contributing to Open Science. The first version of the dataset has been improved and updated based on the comments by the reviewers and me, improving the reproducibility of the analyses. All in all, this paper has improved and I am very glad that I can recommend this for publication, and I’d like to do so with a sentence from the review by Sam Leggett: “this study has a lot of potential to be deployed across other regions, and time periods for similar purposes (Iron Age hoards for instance). And it will be of great interest to Viking Age experts interested in hoards, but also early medieval transport and travel.” References Wilcox, W. 2024a Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England. Zenodo, 7999149, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7999149 Wilcox, W. 2024b Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England (Supplemental Material). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11067607 | Mobility and the reuse of Roman Roads for the deposition of Viking Age silver hoards in North West England | Wyatt Wilcox | <p>Discussions on Viking Age silver hoards in North West England have been dominated by analysis of the material compositions of the hoards. Despite a multi-century research legacy concerning the material composition of the Viking Age silver... |  | Europe, Landscape archaeology, Medieval, Spatial analysis | Ronald Visser | 2023-06-04 22:29:18 | View | |

02 May 2024

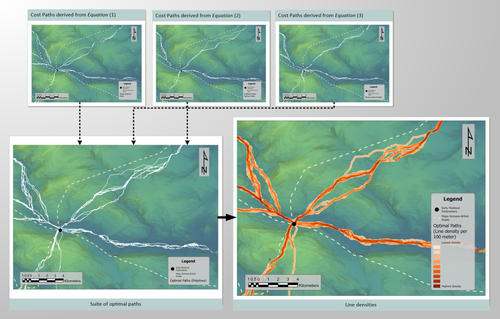

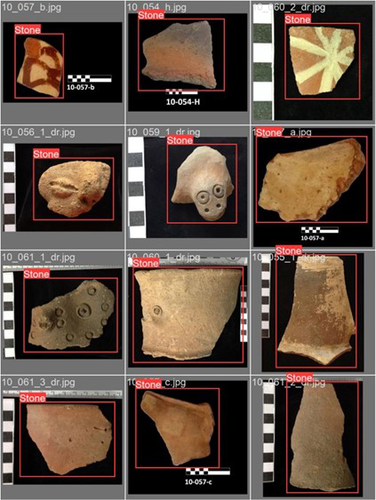

Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard PracticesSharp Kayeleigh, Christofis Brooklyn, Eslamiat Hossein, Nepal Upesh, Osores Mendives Carlos https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307612A step forward in detecting small objects in UAV data for archaeological surveyingRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

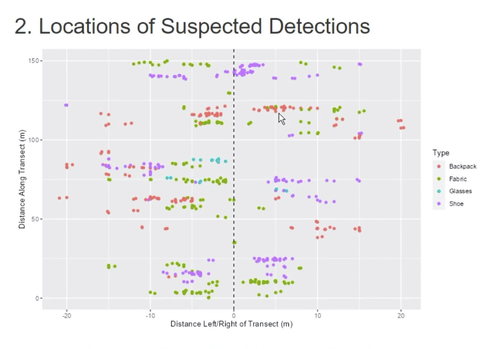

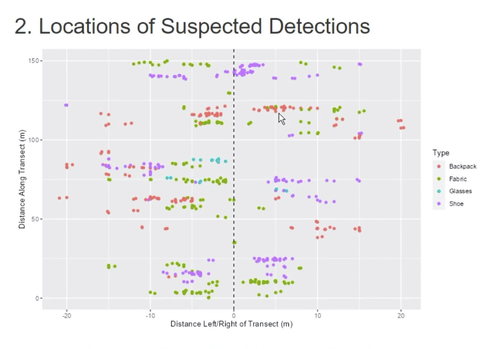

In this paper [1], the authors describe how they apply machine learning with YOLOv5 to classify visual data, aiming to enhance understanding of archaeological phenomena before conducting destructive fieldwork. Despite challenges, the integration of machine learning with remote sensing technology was seen as transformative, enabling precise recording of areas of interest and assessment of environmental risk factors. The paper discusses successes, failures, and future directions in machine learning research, emphasising the need for standardisation and integration of streamlined methods. The application of machine learning techniques facilitates non-destructive analysis of material culture records, improving conservation efforts and offering insights into both past and contemporary phenomena. While the initial use of YOLOv5 showed potential for consistent detection of archaeological features, further refinement and dataset enlargement are deemed necessary for broader application in non-destructive archaeological surveying. The authors advocate for the integration of machine learning tools in archaeological research to save time, resources, and promote ethical digital recording practices. They highlight the importance of standardised methodologies to enhance credibility and reproducibility, aiming to contribute to the ongoing dialogue in computational archaeology. Overall, I think this paper is a good step forward in detecting small objects in UAV data, and contains useful information for similar studies. The aim towards greater reproducibility and standardisation is of course shared more widely in the machine learning community, and this study is a good example of how to approach this. References [1] Sharp, K., Christofis, B., Eslamiat, H., Nepal, U. and Osores Mendives, C. (2024). Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard Practices. Zenodo, 8307612, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8307612 | Machine Learning for UAV and Ground-Captured Imagery: Toward Standard Practices | Sharp Kayeleigh, Christofis Brooklyn, Eslamiat Hossein, Nepal Upesh, Osores Mendives Carlos | <p>Our collaborative work began in 2019 with the intent to overcome obstacles that had arisen from the inability to access curated artifact collections from remote locations. It was our specific aim to not only create digital twins of excavated ob... |  | Ceramics, Computational archaeology, Remote sensing, South America | Alex Brandsen | 2023-09-01 09:56:18 | View | |

02 May 2024

Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the MuseumAntonis G. Dimitriou, Stella Papadopoulou, Maria Dermenoudi, Angeliki Moneda, Vasiliki Drakaki, Andreana Malama, Alexandros Filotheou, Aristidis Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, Anastasios Tzitzis, Spyros Megalou, Stavroula Siachalou, Aggelos Bletsas, Traianos Yioultsis, Anna Maria Velentza, Sofia Pliasa, Nikolaos Fachantidis, Evangelia Tsangaraki, Dimitrios Karolidis, Charalampos Tsoungaris, Panagiota Balafa and Angeliki Koukouvou https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7805387Social Robotics in the Museum: a case for human-robot interaction using RFID TechnologyRecommended by Daniel Carvalho based on reviews by Dominik Hagmann, Sebastian Hageneuer and Alexis PantosThe paper “Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum” (Dimitriou et al 2023) is a relevant contribution to museology and an interface between the public, archaeological discourse and the field of social robotics. It deals well with these themes and is concise in its approach, with a strong visual component that helps the reader to understand what is at stake. The option of demonstrating the different steps that lead to the final construction of the robot is appropriate, so that it is understood that it really is a linked process and not simple tasks that have no connection. The use of RFID technology for topological movement of social robots has been continuously developed (e.g., Corrales and Salichs 2009; Turcu and Turcu 2012; Sequeira and Gameiro 2017) and shown to have advantages for these environments. Especially in the context of a museum, with all the necessary precautions to avoid breaching the public's privacy, RFID labels are a viable, low-cost solution, as the authors point out (Dimitriou et al 2023), and, above all, one that does not require the identification of users. It is in itself part of an ambitious project, since the robot performs several functions and not just one, a development compared to other currents within social robotics (see Hellou et al 2022: 1770 for a description of the tasks given to robots in museums). The robotic system itself also makes effective use of the localization system, both physically, by RFID labels and by knowing how to situate itself with the public visiting the museum, adapting to their needs, which is essential for it to be successful (see Gasteiger, Hellou and Ahn 2022: 690 for the theme of localization). Archaeology can provide a threshold of approaches when it comes to social robotics and this project demonstrates that, bringing together elements of interaction, education and mobility in a single method. Hence, this is a paper with great merit and deserves to be recommended as it allows us to think of the museum as a space where humans and non-humans can converge to create intelligible discourses, whether in the historical, archaeological or cultural spheres. References Dimitriou, A. G., Papadopoulou, S., Dermenoudi, M., Moneda, A., Drakaki, V., Malama, A., Filotheou, A., Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, A., Tzitzis, A., Megalou, S., Siachalou, S., Bletsas, A., Yioultsis, T., Velentza, A. M., Pliasa, S., Fachantidis, N., Tsagkaraki, E., Karolidis, D., Tsoungaris, C., Balafa, P. and Koukouvou, A. (2024). Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum. Zenodo, 7805387, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7805387 Corrales, A. and Salichs, M.A. (2009). Integration of a RFID System in a Social Robot. In: Kim, JH., et al. Progress in Robotics. FIRA 2009. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 44. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03986-7_8 Gasteiger, N., Hellou, M. and Ahn, H.S. (2023). Factors for Personalization and Localization to Optimize Human–Robot Interaction: A Literature Review. Int J of Soc Robotics 15, 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-021-00811-8 Hellou, M., Lim, J., Gasteiger, N., Jang, M. and Ahn, H. (2022). Technical Methods for Social Robots in Museum Settings: An Overview of the Literature. Int J of Soc Robotics 14, 1767–1786 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-022-00904-y Sequeira, J. S., and Gameiro, D. (2017). A Probabilistic Approach to RFID-Based Localization for Human-Robot Interaction in Social Robotics. Electronics, 6(2), 32. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/electronics6020032 Turcu, C. and Turcu, C. (2012). The Social Internet of Things and the RFID-based robots. In: IV International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2012, pp. 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUMT.2012.6459769 | Exploiting RFID Technology and Robotics in the Museum | Antonis G. Dimitriou, Stella Papadopoulou, Maria Dermenoudi, Angeliki Moneda, Vasiliki Drakaki, Andreana Malama, Alexandros Filotheou, Aristidis Raptopoulos Chatzistefanou, Anastasios Tzitzis, Spyros Megalou, Stavroula Siachalou, Aggelos Bletsas, ... | <p>This paper summarizes the adoption of new technologies in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece. RFID technology has been adopted. RFID tags have been attached to the artifacts. This allows for several interactions, including tracki... |  | Conservation/Museum studies, Remote sensing | Daniel Carvalho | 2023-04-10 14:04:23 | View | |

02 May 2024

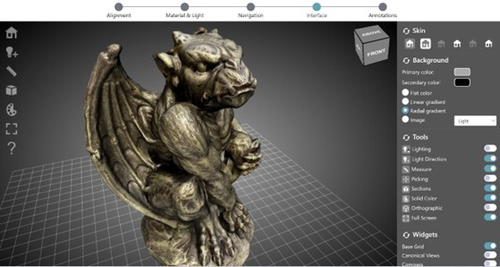

ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: toward full guided publication of high-resolution 3D dataPotenziani, Marco; Ponchio, Federico; Callieri, Marco; Cignoni, Paolo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8075050ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: a new tool for the visual organisation of 3D datasetsRecommended by Ian Moffat based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer, Vayia Panagiotidis, Erik Champion and Martina Trognitz based on reviews by Sebastian Hageneuer, Vayia Panagiotidis, Erik Champion and Martina Trognitz

The manuscript "ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: toward full guided publication of high-resolution 3D data" by Potenziani et al. [1] provides an excellent introduction to the Visual Media Service 3D Configurator. This is an exciting tool, focused on cultural heritage, that forms part of the Visual Media Service, a web-based platform for uploading a range of complex data sets, including high-resolution images, Reflectance Transformation Imaging images and 3D models and transforming them into an appropriate format for interation and visualisation on the web. The 3D Configurator Tool provides researchers with a wizard which assist with the presentation of 3D models. This manuscript provides a history and context for the development of the Visual Media Service and previous related tools such as 3DHOP, Nexus and Relight/OpenLIME. It also provides detailed information about the functionality of the 3D Configurator, including the Alignment, Material & Light, Navigation, Interface and Annotation steps. The Discussion section provides information about applications and users of the Visual Media Service, current limitations and planned future developments. Reviewers Hageneuer, Champion, Trognitz and Panagiotidis all provided important suggestions to the authors which have improved the clarity and scope of this manuscript. While this manscript does not present a case study using this tool, I recommend it to readers as a detailed and clear introduction to the Visual Media Service 3D configurator which may inspire them to use this for their own research. [1] Potenziani, M., Ponchio, F., Callieri, M., and Cignoni, P. (2024). ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: toward full guided publication of high-resolution 3D data. Zenodo, 8075050, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10894515 | ARIADNEplus Visual Media Service 3D configurator: toward full guided publication of high-resolution 3D data | Potenziani, Marco; Ponchio, Federico; Callieri, Marco; Cignoni, Paolo | <p>The use of digital visual media in everyday work is nowadays a common practice in many different domains, including Cultural Heritage (CH). Because of that, the presence of digital datasets in CH archives and repositories is becoming more and m... |  | Computational archaeology | Ian Moffat | 2023-06-23 17:37:47 | View | |

29 Apr 2024

Study and enhancement of the heritage value of a fortified settlement along the Limes Arabicus. Umm ar-Rasas (Amman, Jordan) between remote sensing analysis, photogrammetry and laser scanner surveys.Di Palma Francesca, Gabrielli Roberto, Merola Pasquale, Miccoli Ilaria, Scardozzi Giuseppe https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8306381Integrating remote sensing and photogrammetric approaches to studying a fortified settlement along the Limes Arabicus: Umm ar‐Rasas (Amman, Jordan).Recommended by Alessia Brucato based on reviews by Francesc C. Conesa, Giuseppe Ceraudo and 1 anonymous reviewerDi Palma et alii manuscript delves into applying remote sensing and photogrammetry methods to document and analyze the castrum at the Umm er-Rasas site in Jordan. This research aimed to map all the known archaeological evidence, detect new historical structures, and create a digital archive of the site's features for study and education purposes [1]. Their research has been organized into two phases. The first one consisted of a remote sensing survey and involved collecting historical and modern aerial and satellite imagery, such as: aerial photographs by Sir Marc Aurel Stein from 1939; panchromatic spy satellite images from the Cold War period (Corona KH-4B and Hexagon KH-9); high and very high resolution (HR and VHR) modern multispectral satellite images (Pléiades-1A and Pléiades Neo-4) [1]. This dataset was processed using the ENVI 4.4 software and applying multiple image-enhancing techniques (Pansharpening, RGB composite, data fusion, and Principal Component Analysis). Then, the resulting images were integrated into a QGIS project, allowing for visual analyses of the site's features and terrain. These investigations provided: · a broad overview of the site, · the discovery of a previously unknown archaeological feature (the northeastern dam), · a stage for targeted ground-level investigations [1]. The project's second phase was dedicated to intensive fieldwork operations, including pedestrian surveys, stratigraphic excavations, and photogrammetric recordings, such as: photographic reconstructions via Structure from Motion (SfM) and laser scanner sessions (using two FARO X330 HDR). In particular, the laser scanner data were processed with Reconstructor 4.4, which provided highly detailed 3D models for the QGIS database. These results were crucial in validating the information acquired during the first phase. Overall, the paper is well written, with clear objectives and a systematic presentation of the site [2,3,10,11], the research materials, and the study phases. The dataset was described in meticulous detail (especially the remote sensing sources and the laser scanner recordings). The methods implemented in this study are rigorously described [4,5,6,7,8,9] and show a high level of integration between aerial and field techniques. The results are neatly illustrated and fit into the current debates about the efficacy of remote sensing detection and multiscale approaches in archaeological research. In conclusion, this manuscript significantly contributes to archaeological research, unveiling new and exciting findings about the site of Umm er-Rasas. Its findings and methodologies warrant publication and further exploration. References: 1. Di Palma, F., Gabrielli, R., Merola, P., Miccoli, I. and Scardozzi, G. (2024). Study and enhancement of the heritage value of a fortified settlement along the Limes Arabicus. Umm ar-Rasas (Amman, Jordan) between remote sensing analysis, photogrammetry and laser scanner surveys. Zenodo, 8306381, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8306381 2. Abela J. and Acconci A. (1997), Umm al‐Rasas Kastron Mefa’a. Excavation Campaign 1997. Church of St. Paul: northern and southern flanks. Liber Annus, 47, 484‐488. 3. Bujard J. (2008), Kastron Mefaa, un bourg à l'époque byzantine: Travaux de la Mission archéologique de la Fondation Max van Berchem à Umm al‐Rasas, Jordanie (1988‐1997), PhD diss., University of Fribourg 2008. 4. Cozzolino M., Gabrielli R., Galatà P., Gentile V., Greco G., Scopinaro E. (2019), Combined use of 3D metric surveys and non‐invasive geophysical surveys at the stylite tower (Umm ar‐Rasas, Jordan), Annals of geophysics, 62, 3, 1‐9. http://dx.doi.org/10.4401/ag‐8060 5. Gabrielli R., Salvatori A., Lazzari A., Portarena D. (2016), Il sito di Umm ar‐Rasas – Kastron Mefaa – Giordania. Scavare documentare conservare, viaggio nella ricerca archeologica del CNR. Roma 2016, 236‐240. 6. Gabrielli R., Portarena D., Franceschinis M. (2017), Tecniche di documentazione dei tappeti musivi del sito archeologico di Umm al‐Rasas Kastron Mefaa (Giordania). Archeologia e calcolatori, 28 (1), 201‐218. https://doi.org/10.19282/AC.28.1.2017.12 7. Lasaponara R., Masini N. (2012 ed.), Satellite Remote Sensing: A New Tool for Archaeology, New York 2012. 8. Lasaponara R., Masini N. and Scardozzi G. (2007), Immagini satellitari ad alta risoluzione e ricerca archeologica: applicazioni e casi di studio con riprese pancromatiche e multispettrali di QuickBird. Archeologia e Calcolatori, 18 (2), 187‐227. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33150351.pdf 9. Lasaponara R., Masini N., Scardozzi G. (2010), Elaborazioni di immagini satellitari ad alta risoluzione e ricognizione archeologica per la conoscenza degli insediamenti rurali del territorio di Hierapolis di Frigia (Turchia). Il dialogo dei Saperi – Metodologie integrate per i Beni Culturali, Edizioni scientifiche italiane, 479‐494. 10. Piccirillo M., Abela J. and Pappalardo C. (2007), Umm al‐Rasas ‐ campagna 2007. Rapporto di scavo. Liber Annus, 57, 660‐668. 11. Poidebard A. (1934), La trace de Rome dans le désert de Syrie : le limes de Trajan à la conquête arabe ; recherches aériennes 1925 – 1932. Paris : Geuthner. | Study and enhancement of the heritage value of a fortified settlement along the Limes Arabicus. Umm ar-Rasas (Amman, Jordan) between remote sensing analysis, photogrammetry and laser scanner surveys. | Di Palma Francesca, Gabrielli Roberto, Merola Pasquale, Miccoli Ilaria, Scardozzi Giuseppe | <p>The Limes Arabicus is an excellent laboratory for experimenting with the huge potential of historical remote sensing data for identifying and mapping fortified centres along this sector of the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire and then the B... |  | Antiquity, Asia, Classic, Landscape archaeology, Mediterranean, Remote sensing, Spatial analysis | Alessia Brucato | 2023-08-31 23:34:16 | View | |

22 Apr 2024

The transformation of an archaeological community and its resulting representations in the context of the co-development of open Archaeological Information SystemsEric Lacombe, Dominik Lukas, Sébastien Durost https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309732Exploring The Role of Archaeological Information Systems in Improving Data Management and InteroperabilityRecommended by James Stuart Taylor based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In response to the feedback provided by the reviewers, the authors have undertaken a comprehensive revision of the manuscript [1]. These revisions have specifically targeted the primary concerns raised regarding the clarity and structure of the argument concerning the transformative impact of Archaeological Information Systems (AIS) on archaeological practices. In my view the revised manuscript now more clearly articulates the distinction between internal and external interoperability and emphasizes the critical importance of integrating contextual information with archaeological data. This approach directly addresses the previously identified need for enhanced traceability and usability of archaeological data, ensuring that the manuscript's contributions to the field are both clear and impactful. Moreover, the application of the proposed model at the Bibracte site is illustrated with greater clarity, serving as a concrete example of how the challenges associated with documentation and data management can be effectively addressed through the methodologies proposed in the paper. This practical demonstration enriches the manuscript, providing readers with a much clearer understanding of the model's applicability and benefits in real-world archaeological practice. The authors have also made significant efforts to refine the overall structure and coherence of the manuscript. By making complex concepts more accessible and ensuring a cohesive narrative flow throughout, the manuscript now offers a more engaging and comprehensible read. This has been achieved through careful rephrasing and restructuring of sections, particularly those relating to the T!O model's application and the conclusion, thereby enhancing reader engagement and comprehension. Alongside these structural and conceptual clarifications, explicit discussion of potential areas for future research, not only acknowledges the limitations of the current study but also highlights the significant potential for digital technologies to contribute to archaeological methodology and knowledge production. As such, the manuscript opens up new avenues for exploration and invites further scholarly engagement with the topics it addresses. I believe, these revisions address the earlier feedback quite comprehensively, presenting a robust and compelling argument for the adoption of collaborative and technologically informed approaches in the field of archaeology. The manuscript now stands as a strong example of the critical role AIS could/should play in transforming archaeological practices, offering valuable insights into how these kinds of systems might enhance the management, accessibility, and understanding of archaeological data. Through this revised submission, the authors have significantly strengthened their contribution to the ongoing discourse on digital archaeology, demonstrating the practical and theoretical implications of their work for the broader archaeological community. I am happy, therefore to recommend this paper for acceptence. Reference [1] Lacombe, E., Lukas, D. and Durost, S. (2024). The transformation of an archaeological community and its resulting representations in the context of the co-development of open Archaeological Information Systems. Zenodo, 8309732, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309732

| The transformation of an archaeological community and its resulting representations in the context of the co-development of open Archaeological Information Systems | Eric Lacombe, Dominik Lukas, Sébastien Durost | <p>The adoption of Archaeological Information Systems (AIS) evolves according to multiple factors, both human and technical, as well as endogenous and exogenous. In consequence the ever increasing scope of digital tools, which allow for the organi... |  | Computational archaeology, Europe, Protohistory, Theoretical archaeology | James Stuart Taylor | 2023-09-01 18:58:26 | View | |

22 Apr 2024

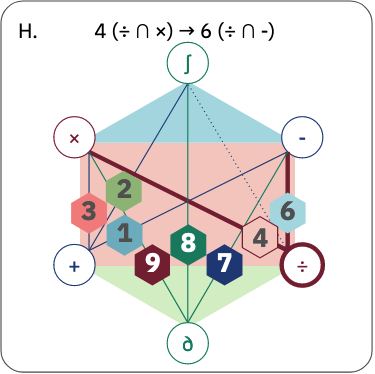

Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of MeaningsYael Alef, Yuval Shafriri https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309992How Semantic Technologies and Spatial Networks Can Enhance Archaeological Resource ManagementRecommended by James Stuart Taylor based on reviews by Dominik Lukas and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Dominik Lukas and 1 anonymous reviewer

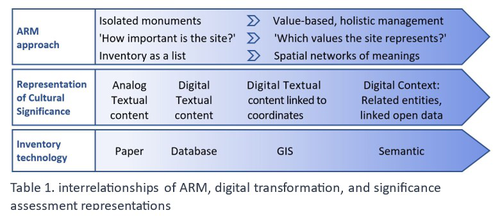

After a thorough review and consideration of the revised manuscript titled "Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text to Spatial Networks of Meanings" by Yael Alef and Yuval Shafriri [1], I am recommending the paper for publication. The authors have made significant strides in addressing the feedback from the initial review process, notably enhancing the manuscript's clarity, methodological detail, and overall contribution to the field of Archaeological Resource Management (ARM). On balance I think the paper competently navigates the shift from a traditional significance-focused assessment of isolated archaeological sites to a more holistic and interconnected approach, leveraging graph data models and spatial networks. This transition represents an advancement in the field, offering deeper insights into the sociocultural dynamics of archaeological sites. The case study of ancient synagogues in northern Israel, particularly the Huqoq Synagogue, serves as a compelling illustration of the potential of semantic technologies to enrich our understanding of cultural heritage. Significantly, the authors have responded to the call for a clearer methodological framework by providing a more detailed exposition of their use of knowledge graph visualization and semantic technologies. This response not only strengthens the paper's scientific rigor but also enhances its accessibility and applicability to a broader audience within the conservation and heritage management community. However, I do think it remains important to acknowledge areas where further work could enrich the paper's contribution. While the manuscript makes notable advancements in the technical and methodological domains, the exploration of the ethical and political implications of semantic technologies in ARM remains less developed. Recognizing the complex interplay of ethical and political considerations in archaeological assessments is crucial for the responsible advancement of the field. Thus, I suggest that future work could productively focus on these dimensions, offering a more comprehensive view of the implications of integrating semantic technologies into heritage management practices. I don't think that this omission is a reason to withold the paper for publication or seek further review. In fact I think it stands alone a paper quite well. Perhaps the authors might consider this as a complementary line of inquiry in their future work in the field. In conclusion then, I believe the revised manuscript represents a valuable addition to the literature, pushing boundaries of how we assess, understand, and manage archaeological resources. Its focus on semantic technologies and the creation of spatial networks of meanings marks a significant step forward in the field. I believe its publication will stimulate further research and discussion, particularly in the realms of ethical and political considerations, which remain ripe for exploration. Therefore, I'm happy to endorse the publication of this manuscript. Reference [1] Alef, Y and Shafriri, Y. (2024). Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of Meanings. Zenodo, 8309992, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8309992 | Cultural Significance Assessment of Archaeological Sites for Heritage Management: From Text of Spatial Networks of Meanings | Yael Alef, Yuval Shafriri | <p>This study examines the shift towards a values-based approach for Archaeological Resource Management (ARM), emphasizing the integration of Context-Based Significance Assessment (CBSA) with semantic technologies into digital ARM inventories. We ... |  | Computational archaeology, Conservation/Museum studies, Spatial analysis | James Stuart Taylor | 2023-09-01 22:24:15 | View | |

16 Apr 2024

Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin DatasetSebastian Gampe, Karsten Tolle https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298077A significant contribution to the problem of unbalanced data in machine learning research in archaeologyRecommended by Alex Brandsen based on reviews by Simon Carrignon, Joel Santos and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Carrignon, Joel Santos and 1 anonymous reviewer

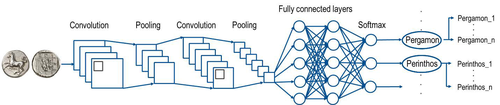

This paper [1] presents an innovative approach to address the prevalent challenge of unbalanced datasets in coin type recognition, shifting the focus from coin class type recognition to coin mint recognition. Despite this shift, the issue of unbalanced data persists. To mitigate this, the authors introduce a method to split larger classes into smaller ones, integrating them into an 'additional class layer'. Three distinct machine learning (ML) methodologies were employed to identify new possible classes, with one approach utilising unsupervised clustering alongside manual intervention, while the others leverage object detection, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. However, despite these efforts, overfitting remained a persistent issue, prompting the authors to explore alternative methods such as dataset improvement and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). The paper contributes significantly to the intersection of ML techniques and archaeology, particularly in addressing overfitting challenges. Furthermore, the authors' candid acknowledgment of the limitations of their approaches serves as a valuable resource for researchers encountering similar obstacles. This study stems from the D4N4 project, aimed at developing a machine learning-based coin recognition model for the extensive "Corpus Nummorum" dataset, comprising over 19,600 coin types and 49,000 coins from various ancient landscapes. Despite encountering challenges with overfitting due to the dataset's imbalance, the authors' exploration of multiple methodologies and transparent documentation of their limitations enriches the academic discourse and provides a foundation for future research in this field. Reference [1] Gampe, S. and Tolle, K. (2024). Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin Dataset. Zenodo, 8298077, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8298077 | Creating an Additional Class Layer with Machine Learning to counter Overfitting in an Unbalanced Ancient Coin Dataset | Sebastian Gampe, Karsten Tolle | <p>We have implemented an approach based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for mint recognition for our Corpus Nummorum (CN) coin dataset as an alternative to coin type recognition, since we had too few instances for most of the types (classe... |  | Computational archaeology | Alex Brandsen | 2023-08-29 16:26:41 | View | |

12 Apr 2024

Survey Planning, Allocation, Costing and Evaluation (SPACE) Project: Developing a Tool to Help Archaeologists Conduct More Effective SurveysE. B. Banning, Steven Edwards, and Isaac Ullah https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8072178A new tool to increase the robustness of archaeological field surveyRecommended by Jitte Waagen based on reviews by Philip Verhagen and Tymon de Haas based on reviews by Philip Verhagen and Tymon de Haas

This well-written and interesting paper ‘Survey Planning, Allocation, Costing and Evaluation (SPACE) Project: Developing a Tool to Help Archaeologists Conduct More Effective Surveys’ deals with the development of a ‘modular, accessible, and simple web-based platform for survey planning and quality assurance’ in the area of pedestrian field survey methods (Banning et al. 2024). Although there have been excellent treatments of statistics in archaeological field survey (among which various by the first author: Banning 2020, 2021), and there is continuous methodological debate on platforms such as the International Mediterranean Survey Workshop (IMSW), in papers dealing with the current development and state of the field (Knodell et al. 2023), good practices (Attema et al. 2020) or the merits of a quantifying approach to archaeological densities (cf. de Haas et al. 2023), this paper rightfully addresses the lack of rigorous statistical approaches in archaeological field survey. As argued by several scholars such as Orton (2000), this mainly appears the result of lack of knowledge/familiarity/resources to bring in the required expertise etc. with the application of seemingly intricate statistics (cf. Waagen 2022). In this context this paper presents a welcome contribution to the feasibility of a robust archaeological field survey design. The SPACE application, under development by the authors, is introduced in this paper. It is a software tool that aims to provide different modules to assist archaeologists to make calculations for sample size, coverage, stratification, etc. under the conditions of survey goals and available resources. In the end, the goal is to ensure archaeological field surveys will attain their objectives effectively and permit more confidence in the eventual outcomes. The module concerning Sweep Widths, an issue introduced by the main author in 2006 (Banning 2006) is finished; the sweep width assessment is a methodology to calibrate one’s survey project for artefact types, landscape, visibility and person-bound performance, eventually increasing the quality (comparability) of the collected samples. This is by now a well-known calibration technique, yet little used, so this effort to make that more accessible is certainly laudable. An excellent idea, and another aim of this project, is indeed to build up a database with calibration data, so applying sweep-width corrections will become easier accessible to practitioners who lack time to set up calibration exercises. It will be very interesting to have a closer look at the eventual platform and to see if, and how, it will be adapted by the larger archaeological field survey community, both from an academic research perspective as from a heritage management point of view. I happily recommend this paper and all debate relating to it, including the excellent peer reviews of the manuscript by Philip Verhagen and Tymon de Haas (available as part of this PCI recommendation procedure), to any practitioner of archaeological field survey. References Attema, P., Bintliff, J., Van Leusen, P.M., Bes, P., de Haas, T., Donev, D., Jongman, W., Kaptijn, E., Mayoral, V., Menchelli, S., Pasquinucci, M., Rosen, S., García Sánchez, J., Luis Gutierrez Soler, L., Stone, D., Tol, G., Vermeulen, F., and Vionis. A. 2020. “A guide to good practice in Mediterranean surface survey projects”, Journal of Greek Archaeology 5, 1–62. https://doi.org/10.32028/9781789697926-2 Banning, E.B., Alicia L. Hawkins, S.T. Stewart, Sweep widths and the detection of artifacts in archaeological survey, Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 38, Issue 12, 2011, Pages 3447-3458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.08.007 Banning, E.B. 2020. Spatial Sampling. In: Gillings, M., Hacıgüzeller, P., Lock, G. (eds.) Archaeological Spatial Analysis. A Methodological Guide. Routledge. Banning, E.B. 2021. Sampled to Death? The Rise and Fall of Probability Sampling in Archaeology. American Antiquity, 86(1), 43-60. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2020.39 Banning, E. B. Steven Edwards, & Isaac Ullah. (2024). Survey Planning, Allocation, Costing and Evaluation (SPACE) Project: Developing a Tool to Help Archaeologists Conduct More Effective Surveys. Zenodo, 8072178, ver. 9 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8072178 Knodell, A.R., Wilkinson, T.C., Leppard, T.P. et al. 2023. Survey Archaeology in the Mediterranean World: Regional Traditions and Contributions to Long-Term History. J Archaeol Res 31, 263–329 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-022-09175-7 Orton, C. 2000. Sampling in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139163996 Waagen, J. 2022. Sampling past landscapes. Methodological inquiries into the bias problems of recording archaeological surface assemblages. PhD-Thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/e9cb922c-c7e4-40a1-b648-7b8065c46880 de Haas, T., Leppard, T. P., Waagen, J., & Wilkinson, T. (2023). Myopic Misunderstandings? A Reply to Meyer (JMA 35(2), 2022). Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 36(1), 127-137. https://doi.org/10.1558/jma.27148 | Survey Planning, Allocation, Costing and Evaluation (SPACE) Project: Developing a Tool to Help Archaeologists Conduct More Effective Surveys | E. B. Banning, Steven Edwards, and Isaac Ullah | <p>Designing an effective archaeological survey can be complicated and confidence that it was effective requires post-survey evaluation. The goal of SPACE is to develop software to facilitate survey designers’ decisions and partially automate tool... |  | Computational archaeology, Landscape archaeology | Jitte Waagen | 2023-06-28 13:42:28 | View |

FOLLOW US

MANAGING BOARD

Alain QUEFFELEC

Nelson ALMEIDA

Johan ARIF

Marta ARZARELLO

Ruth BLASCO

Matthew COLLINS

Otis CRANDELL

Luc DOYON

Alice LEPLONGEON

Florent RIVALS

Aitor RUIZ-REDONDO